Biology:Wound licking

Wound licking is an instinctive response in humans and many other animals to cover an injury or second degree burn[1] with saliva. Dogs, cats, small rodents, horses, and primates all lick wounds.[2] Saliva contains tissue factor which promotes the blood clotting mechanism. The enzyme lysozyme is found in many tissues and is known to attack the cell walls of many gram-positive bacteria, aiding in defense against infection. Tears are also beneficial to wounds due to the lysozyme enzyme. However, there are also infection risks due to bacteria in the mouth.

Mechanism

Oral mucosa heals faster than skin,[3] suggesting that saliva may have properties that aid wound healing. Saliva contains cell-derived tissue factor, and many compounds that are antibacterial or promote healing. Salivary tissue factor, associated with microvesicles shed from cells in the mouth, promotes wound healing through the extrinsic blood coagulation cascade.[4][5][6] The enzymes lysozyme and peroxidase,[7] defensins,[8] cystatins and an antibody, IgA,[9] are all antibacterial. Thrombospondin and some other components are antiviral.[10][11] A protease inhibitor, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, is present in saliva and is both antibacterial and antiviral, and a promoter of wound healing.[12][13] Nitrates that are naturally found in saliva break down into nitric oxide on contact with skin, which will inhibit bacterial growth.[14] Saliva contains growth factors[15] such as epidermal growth factor,[16] VEGF,[17] TGF-β1,[18] leptin,[19][20] IGF-I,[21][22] lysophosphatidic acid,[23][24] hyaluronan[25] and NGF,[26][27][28] which all promote healing, although levels of EGF and NGF in humans are much lower than those in rats. In humans, histatins may play a larger role.[29][30] As well as being growth factors, IGF-I and TGF-α induce antimicrobial peptides.[31] Saliva also contains an analgesic, opiorphin.[32] Licking will also tend to debride the wound and remove gross contamination from the affected area. In a recent study, scientists have confirmed through several experiments that the protein responsible for healing properties in human saliva is, in fact, histatin. Scientists are now looking for ways to make use of this information in ways that can lead to chronic wounds, burns, and injuries being healed by saliva.[33]

In animals

It has been long observed that the licking of their wounds by dogs might be beneficial. Indeed, a dog's saliva is bactericidal against the bacteria Escherichia coli and Streptococcus canis, although not against coagulase-positive Staphylococcus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[34] Wound licking is also important in other animals. Removal of the salivary glands of mice[35] and rats slows wound healing, and communal licking of wounds among rodents accelerates wound healing.[36][37] Communal licking is common in several primate species. In macaques, hair surrounding a wound and any dirt is removed, and the wound is licked, healing without infection.[38]

Risks

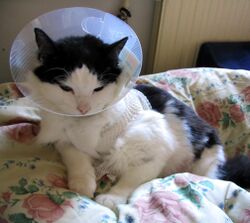

Wound licking is beneficial but too much licking can be harmful. An Elizabethan collar may be used on pet animals to prevent them from biting an injury or excessively licking it, which can cause a lick granuloma. These lesions are often infected by pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus intermedius.[39] Horses that lick wounds may become infected by a stomach parasite, Habronema, a type of nematode worm. The rabies virus may be transmitted between animals, such as the kudu antelopes by wound licking of wounds with residual infectious saliva.[40]

In humans

Religion and legend

There are many legends involving healing wounds by licking them or applying saliva. Saint Magdalena de Pazzi is said to have cured a nun of sores and scabs in 1589 by licking her limbs.[41] The Roman Emperor Vespasian is said to have performed a healing of a blind man using his saliva.[42] Pliny the Elder in his Natural History reported that a fasting woman's saliva is an effective cure for bloodshot eyes.[43]

In the Hebrew Bible saliva is associated with uncleanliness. However, in the Gospels, there are three different incidents in which Jesus uses saliva to cure (Mark 7:33, Mark 8:23, John 9:6). Köstenberger suggests "by using saliva to cure a man, Jesus claims to possess unusual spiritual authority."[44]

Risks

There are potential health hazards in wound licking due to infection risk, especially in immunocompromised patients. Human saliva contains a wide variety of bacteria that are harmless in the mouth, but that may cause significant infection if introduced into a wound. A notable case was a diabetic man who licked his bleeding thumb following a minor bicycle accident, and subsequently had to have the thumb amputated after it became infected with Eikenella corrodens from his saliva.[45]

Licking of people's wounds by animals

History and legend

Dog saliva has been said by many cultures to have curative powers in people.[46][47] "Langue de chien, langue de médecin" is a French saying meaning "A dog's tongue is a doctor's tongue", and a Latin quote that "Lingua canis dum lingit vulnus curat" or "A dog's saliva can heal your wound" appears in a thirteenth-century manuscript.[48] In Ancient Greece , dogs at the shrine of Aesculapius were trained to lick patients, and snake saliva was also applied to wounds.[49] Saint Roch in the Middle Ages was said to have been cured of a plague of sores by licking from his dog.[50] The Assyrian Queen Semiramis is supposed to have attempted to resurrect the slain Armenian king Ara the Beautiful by having the dog god Aralez lick his wounds.[51] In the Scottish Highlands in the nineteenth century, dog saliva was believed to be effective for treating wounds and sores.[52] In the Gospel of Luke (16:19-31), Lazarus the Beggar's sores are licked by dogs, although no curative effects are reported by the Evangelist.[citation needed]

Modern cases

There are contemporary reports of the healing properties of dog saliva. Fijian fishermen are reported to allow dogs to lick their wounds to promote healing,[14] and a case of dog saliva promoting wound healing was reported in the Lancet medical journal.[53]

Risks

As with the licking of wounds by people, wound licking by animals carries a risk of infection. Allowing pet cats to lick open wounds can cause cellulitis[54][55] and sepsis[56][57] due to bacterial infections. Licking of open wounds by dogs could transmit rabies if the dog is infected with rabies,[58] although this is said by the CDC to be rare.[59] Dog saliva has been reported to complicate the healing of ulcers.[60] Another issue is the possibility of an allergy to proteins in the saliva of pets, such as Fel d 1 in cat allergy and Can f 1 in dog allergy.[61] Cases of serious infection following the licking of wounds by pets include:

- Dog

- A diabetic man who was infected by Pasteurella dagmatis due to the licking of his injured toe by his dog, causing a spinal infection.[62]

- A woman recovering from knee surgery suffered a persistent infection of the knee with Pasteurella after her dog licked a small wound on her toe.[63][64]

- A dog lick to an Australian woman's minor burn caused sepsis and necrosis due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus infection, resulting in the loss of all her toes, fingers and a leg.[65][66]

- C. canimorsus caused acute kidney failure due to sepsis in a man whose open hand wound was licked by his dog.[67]

- A 68-year-old man died from sepsis and necrotizing fasciitis after a wound was licked by his dog.[68]

- A patient with a perforated eardrum developed meningitis after his dog passed on a Pasteurella multocida infection by licking his ear.[69]

- Cat

- A woman recovering from surgery for endometrial cancer suffered from Pasteurella multocida infection causing an abscess after her cat licked the incision.[70]

- A blood donor whose cat licked her chapped fingers passed on Pasteurella infection to a 74-year-old transfusion recipient.[71]

- A seven-week-old boy contracted meningitis due to Pasteurella from contact with pet saliva.[72]

Idiomatic use

To "lick your wounds" means to "withdraw temporarily while recovering from a defeat"[73]

The phrase was spoken by Antony in John Dryden's seventeenth century play All for Love:[74]

They look on us at distance, and, like curs

Scaped from the lion's paws, they bay far off

And lick their wounds, and faintly threaten war.

See also

- Cat scratch fever

- Folklore

- Maggot therapy

- Personal grooming

- Skin repair

- Vampire bat feeding

- Zoonosis

References

- ↑ Putro, Budi Cahyono; Dachlan, Ishandono (2018). "The effect of human saliva compared to Aloe vera on wound healing of 2 nd degree burn injury in animal models". Journal of Thee Medical Sciences (Berkala Ilmu Kedokteran) 50 (4). doi:10.19106/JMEDSCIE/005004201801.

- ↑ Engel, Cindy (2003). Wild Health: Lessons in Natural Wellness from the Animal Kingdom. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780618340682. https://archive.org/details/wildhealthhowani00cind.

- ↑ "Differential Injury Responses in Oral Mucosal and Cutaneous Wounds". J. Dent. Res. 82 (8): 621–6. August 2003. doi:10.1177/154405910308200810. PMID 12885847.

- ↑ "The mechanism of the action of saliva in blood coagulation". Am J Physiol 125: 108–12. 1938. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1938.125.1.108.

- ↑ "Cell-derived vesicles exposing coagulant tissue factor in saliva". Blood 117 (11): 3172–80. 2011. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-06-290460. PMID 21248061.

- ↑ Gross PL (2011). "Salivary microvesicles clot blood". Blood 117 (11): 2989. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-332759. PMID 21415275.

- ↑ "Origin, structure, and biological activities of peroxidases in human saliva". Arch Biochem Biophys 445 (2): 261–8. January 2006. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.004. PMID 16111647.

- ↑ "Defensins in saliva and the salivary glands". Med Electron Microsc 36 (4): 247–52. 2003. doi:10.1007/s00795-003-0225-0. PMID 16228657.

- ↑ "Biochemical composition of human saliva in relation to other mucosal fluids". Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 6 (2): 161–75. 1995. doi:10.1177/10454411950060020501. PMID 7548622.

- ↑ "Oral transmission of HIV, reality or fiction? An update". Oral Dis 12 (3): 219–28. May 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01187.x. PMID 16700731. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118633302/abstract.

- ↑ "Innate antiviral defenses in body fluids and tissues". Antiviral Res. 48 (2): 71–89. November 2000. doi:10.1016/S0166-3542(00)00126-1. PMID 11114410.

- ↑ "Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor mediates non-redundant functions necessary for normal wound healing". Nat. Med. 6 (10): 1147–53. October 2000. doi:10.1038/80489. PMID 11017147.

- ↑ Kate Wong: A Protein's Healing Powers. Scientific American 2 October 2000

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Wound licking and nitric oxide". Lancet 349 (9067): 1776. June 1997. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63002-4. PMID 9193412. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)63002-4/fulltext.

- ↑ "Saliva and growth factors: the fountain of youth resides in us all". J. Dent. Res. 74 (12): 1826–32. December 1995. doi:10.1177/00220345950740120301. PMID 8600176.

- ↑ Jahovic N, Güzel E, Arbak S, Yeğen BC (September 2004). "The healing-promoting effect of saliva on skin burn is mediated by epidermal growth factor (EGF): role of the neutrophils". Burns 30 (6): 531–8. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2004.02.007. PMID 15302417.

- ↑ "Vascular endothelial growth factor is constitutively expressed in normal human salivary glands and is secreted in the saliva of healthy individuals". J. Pathol. 186 (2): 186–91. October 1998. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(1998100)186:2<186::AID-PATH148>3.0.CO;2-J. PMID 9924435. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/1260/abstract.

- ↑ "Site-specific production of TGF-beta in oral mucosal and cutaneous wounds". Wound Repair Regen 16 (1): 80–6. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00320.x. PMID 18086295. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119413518/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ↑ "Leptin enhances wound re-epithelialization and constitutes a direct function of leptin in skin repair". J. Clin. Invest. 106 (4): 501–9. August 2000. doi:10.1172/JCI9148. PMID 10953025.

- ↑ "Salivary leptin induces increased expression of growth factors in oral keratinocytes". J. Mol. Endocrinol. 34 (2): 353–66. April 2005. doi:10.1677/jme.1.01658. PMID 15821102. http://jme.endocrinology-journals.org/cgi/content/full/34/2/353.

- ↑ "Free insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-II in human saliva". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 66 (5): 1014–8. May 1988. doi:10.1210/jcem-66-5-1014. PMID 3360895.

- ↑ "Insulin-like growth factor-I in wound healing of rat skin". Regul. Pept. 150 (1–3): 7–13. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2008.05.006. PMID 18597865.

- ↑ "Lysophosphatidic acid, a growth factor-like lipid, in the saliva". J. Lipid Res. 43 (12): 2049–55. December 2002. doi:10.1194/jlr.M200242-JLR200. PMID 12454265.

- ↑ "Topical application of the phospholipid growth factor lysophosphatidic acid promotes wound healing in vivo". Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 280 (2): R466–72. 1 February 2001. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.2.R466. PMID 11208576.

- ↑ "Hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid) and its regulation in human saliva by hyaluronidase and its inhibitors". J Oral Sci 45 (2): 85–91. June 2003. doi:10.2334/josnusd.45.85. PMID 12930131. http://jos.dent.nihon-u.ac.jp/journal/45/2/085.pdf.

- ↑ "Nerve growth factor: acceleration of the rate of wound healing in mice". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 (7): 4379–81. July 1980. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.7.4379. PMID 6933491. Bibcode: 1980PNAS...77.4379L.

- ↑ "Nerve growth factor and wound healing". NGF and Related Molecules in Health and Disease. Progress in Brain Research. 146. 2004. 369–84. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(03)46023-8. ISBN 978-0-444-51472-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=bBmjiVUTsuEC&pg=PA369.

- ↑ "Nerve growth factor concentration in human saliva". Oral Dis 13 (2): 187–92. March 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01265.x. PMID 17305621. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118545038/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ↑ "Histatins are the major wound-closure stimulating factors in human saliva as identified in a cell culture assay". FASEB J. 22 (11): 3805–12. November 2008. doi:10.1096/fj.08-112003. PMID 18650243.

- ↑ Wright K (28 December 2008). "Top 100 Stories of 2008 #62: Researchers Discover Why Wound-Licking Works". Discover Magazine. http://discovermagazine.com/2009/jan/062.

- ↑ "Wound healing and expression of antimicrobial peptides/polypeptides in human keratinocytes, a consequence of common growth factors". J. Immunol. 170 (11): 5583–9. 1 June 2003. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5583. PMID 12759437.

- ↑ "Human Opiorphin, a natural antinociceptive modulator of opioid-dependent pathways". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (47): 17979–84. November 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605865103. PMID 17101991. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10317979W.

- ↑ Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. "Licking Your Wounds: Scientists Isolate Compound in Human Saliva That Speeds Wound Healing." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 24 July 2008.

- ↑ "Antibacterial properties of saliva: role in maternal periparturient grooming and in licking wounds". Physiol. Behav. 48 (3): 383–6. September 1990. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(90)90332-X. PMID 2125128.

- ↑ "The effect of selective desalivation on wound healing in mice". Exp. Gerontol. 26 (4): 357–63. 1991. doi:10.1016/0531-5565(91)90047-P. PMID 1936194.

- ↑ "Effect of salivary glands on wound contraction in mice". Nature 279 (5716): 793–5. June 1979. doi:10.1038/279793a0. PMID 450129. Bibcode: 1979Natur.279..793H.

- ↑ Bodner L (1991). "Effect of parotid submandibular and sublingual saliva on wound healing in rats". Comp Biochem Physiol A 100 (4): 887–90. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(91)90309-Z. PMID 1685381.

- ↑ "Individual and social behavioral responses to injury in wild toque macaques (Macaca Sinica)". International Journal of Primatology 10 (3): 215–34. 1989. doi:10.1007/BF02735201.

- ↑ "Microbiological and histopathological features of canine acral lick dermatitis". Veterinary Dermatology 19 (5): 288–98. October 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3164.2008.00693.x. PMID 18699812.

- ↑ "A molecular epidemiological study of rabies epizootics in kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) in Namibia". BMC Vet. Res. 2: 2. 2006. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-2-2. PMID 16412222.

- ↑ Fabrini, Placido; Isoleri, Antonio (1900). The life of St. Mary Magdalen De-Pazzi : Florentine noble, sacred Carmelite virgin. Philadelphia. https://archive.org/details/thelifeofstmarym00fabruoft.

- ↑ Eve E (2008). "Spit in Your Eye: The Blind Man of Bethsaida and the Blind Man of Alexandria". New Testament Studies 54: 1–17. doi:10.1017/S0028688508000015.

- ↑ "Pliny Natural History: Book XXVIII: Chapter XXIII" (in en). https://www.loebclassics.com/view/pliny_elder-natural_history/1938/pb_LCL418.55.xml?readMode=recto.

- ↑ Köstenberger, Andreas J. (December 2004) (in en). John. Baker Academic. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-8010-2644-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=b9SXH_KuTwIC.

- ↑ "Potential hazard of wound licking". N. Engl. J. Med. 346 (17): 1336. April 2002. doi:10.1056/NEJM200204253461721. PMID 11973376. https://content.nejm.org/cgi/reprint/346/17/1329.pdf?ck=nck.

- ↑ Hatfield, Gabrielle (2004). Encyclopedia of Folk Medicine: Old World and New World Traditions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078747. https://books.google.com/books?id=2GGz6708nqgC.

- ↑ Daniels, Cora Linn; C. M. Stevans (2003). Encyclopfdia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences of the World (Volume II). Minerva Group Inc.. pp. 668. ISBN 9781410209153. https://books.google.com/books?id=Aft4c9GauRsC.

- ↑ The Aberdeen Bestiary, a thirteenth-century English illuminated manuscript

- ↑ "Healing rituals and sacred serpents". Lancet 340 (8813): 223–5. July 1992. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)90480-Q. PMID 1353146.

- ↑ Serpell, James (1996). In the Company of Animals: A Study of Human-animal Relationships. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521577793. https://books.google.com/books?id=v9gKhfo0MDgC.

- ↑ Ananikian, Mardiros (1925). Armenian Mythology in The Mythology of All Races Volume VII. New York: Archaeological Institute of America, Marshall Jones Co.. http://rbedrosian.com/ananik5c.htm.

- ↑ Gregor, Walter (1881). Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North-East of Scotland. Forgotten Books. pp. 251. ISBN 978-1-60506-178-8. http://www.forgottenbooks.org/info/Notes_on_the_FolkLore_of_the_NorthEast_of_Scotland. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ↑ Verrier L (March 1970). "Dog licks man". Lancet 1 (7647): 615. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)91650-8. PMID 4190562.

- ↑ "Complicated infections of skin and skin structures: when the infection is more than skin deep". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53 (Suppl 2): ii37–50. June 2004. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh202. PMID 15150182. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/53/suppl_2/ii37.pdf.

- ↑ "An unusual case of diabetic cellulitis due to Pasturella multocida". J Foot Ankle Surg 34 (1): 91–5. 1995. doi:10.1016/S1067-2516(09)80109-9. PMID 7780401.

- ↑ "[Septic shock caused by Pasteurella multocida in alcoholic patients. Probable contamination of leg ulcers by the saliva of the domestic cats]" (in fr). Presse Med 29 (16): 1455–7. September 2000. PMID 11039085.

- ↑ "Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia: fifth report of a cat-associated infection and five other cases". Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14 (6): 520–3. June 1995. doi:10.1007/BF02113430. PMID 7588825.

- ↑ "Should travellers in rabies endemic areas receive pre-exposure rabies immunization?". Ann Med Interne 145 (6): 409–11. 1994. PMID 7864502.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (July 2004). "Investigation of rabies infections in organ donor and transplant recipients—Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, 2004". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53 (26): 586–9. PMID 15241303. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm53d701a1.htm.

- ↑ Knowles J (27 January – 2 February 2000). "Dog saliva complicates the healing of ulcers". Nurs Times 96 (4 Suppl): 8. PMID 10827733.

- ↑ "The major dog allergens, Can f 1 and Can f 2, are salivary lipocalin proteins: cloning and immunological characterization of the recombinant forms". Immunology 92 (4): 577–86. December 1997. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00386.x. PMID 9497502.

- ↑ "Pasteurella dagmatis spondylodiscitis in a diabetic patient" (in fr). Rev Méd Interne 27 (10): 803–4. October 2006. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2006.05.018. PMID 16978746.

- ↑ "Pasteurella multocida infection of a total knee arthroplasty after a "dog lick"". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14 (10): 993–7. October 2006. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0022-5. PMID 16468067.

- ↑ Low, Stephanie Chiang-Mei; Greenwood, John Edward (2008). "Capnocytophaga canimorsus: infection, septicaemia, recovery and reconstruction". Journal of Medical Microbiology 57 (7): 901–903. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47756-0. ISSN 0022-2615. PMID 18566152.

- ↑ "Capnocytophaga canimorsus: infection, septicaemia, recovery and reconstruction". J. Med. Microbiol. 57 (Pt 7): 901–3. July 2008. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.47756-0. PMID 18566152.

- ↑ Staff writers (25 July 2008). "Woman loses leg, fingers, toes from dog lick". Herald Sun. http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/story/0,21985,24075396-661,00.html.

- ↑ "A lick may be as bad as a bite: irreversible acute renal failure". Nephrol Dial Transplant 15 (11): 1883–4. 2000. doi:10.1093/ndt/15.11.1883. PMID 11071985. http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/15/11/1883.

- ↑ Ko Chang; L. K. Siu; Yen-Hsu Chen; Po-Liang Lu; Tun-Chieh Chen; Hsiao-Chen Hsieh; Chun-Lu Lin (2007). "Fatal Pasteurella multocida septicemia and necrotizing fasciitis related with wound licked by a domestic dog". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 39 (2): 167–70. doi:10.1080/00365540600786572. PMID 17366037.

- ↑ "Beware of dogs licking ears". Lancet 354 (9186): 1267–8. 1999. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04197-5. PMID 10520644. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(99)04197-5/fulltext.

- ↑ "Postoperative wound infection with Pasteurella multocida from a pet cat". Am J Obstet Gynecol 188 (4): 1115–6. April 2003. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.266. PMID 12712125.

- ↑ "Pasteurella multocida bacteremia in asymptomatic plateletpheresis donors: a tale of two cats". Transfusion 47 (11): 1984–9. November 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01421.x. PMID 17958526. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118485274/abstract.

- ↑ "Pasteurella multocida meningitis in infancy – (a lick may be as bad as a bite)". Eur J Pediatr 158 (11): 875–8. November 1999. doi:10.1007/s004310051232. PMID 10541939.

- ↑ wikt:To lick one's wounds

- ↑ Dryden, John (1677). All for Love, or the World Well Lost. http://johndryden.classicauthors.net/AllForLove/AllForLove7.html. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

|