Biography:Edgar Adrian

The Right Honourable The Lord Adrian | |

|---|---|

| |

| 49th President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1950–1955 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Robert Robinson |

| Succeeded by | Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hampstead, London, England |

| Died | 4 August 1977 (aged 87) Cambridge, England |

| Spouse(s) | Hester Adrian (m. 1923) |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society[1] Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1932) Royal Medal (1934) Copley Medal (1946) Albert Medal (1953) Karl Spencer Lashley Award (1961) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biology (electrophysiology) |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge |

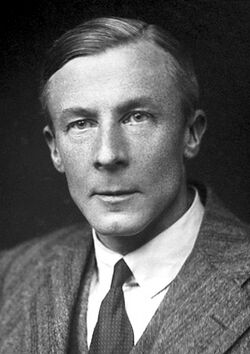

Edgar Douglas Adrian, 1st Baron Adrian OM FRS (30 November 1889 – 4 August 1977)[2][3] was an English electrophysiologist and recipient of the 1932 Nobel Prize for Physiology, won jointly with Sir Charles Sherrington for work on the function of neurons. He provided experimental evidence for the all-or-none law of nerves.[1][4]

Biography

Adrian was born in Hampstead, London, the youngest son of Alfred Douglas Adrian, legal adviser to the Local Government Board, and Flora Lavinia Barton.[5]

He was educated at Westminster School and then studied Natural Sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1911. In 1913 he was elected to a fellowship of Trinity College on account of his research into the "all or none" law of nerves.

After completing a medical degree (MB BCh) in 1915, he undertook clinical work at St Bartholomew's Hospital London during World War I, treating soldiers with nerve damage and nervous disorders such as shell shock. Adrian returned to Cambridge as a lecturer gaining his doctorate (MD) in 1919 and in 1925 began research on the human sensory organs by electrical methods.

Career

Continuing earlier studies of Keith Lucas, he used a capillary electrometer and cathode ray tube to amplify the signals produced by the nervous system and was able to record the electrical discharge of single nerve fibres under physical stimulus. (It seems he used frogs in his experiments[6]) An accidental discovery by Adrian in 1928 proved the presence of electricity within nerve cells. Adrian said,

I had arranged electrodes on the optic nerve of a toad in connection with some experiments on the retina. The room was nearly dark and I was puzzled to hear repeated noises in the loudspeaker attached to the amplifier, noises indicating that a great deal of impulse activity was going on. It was not until I compared the noises with my own movements around the room that I realised I was in the field of vision of the toad's eye and that it was signalling what I was doing.

A key result, published in 1928, stated that the excitation of the skin under constant stimulus is initially strong but gradually decreases over time, whereas the sensory impulses passing along the nerves from the point of contact are constant in strength, yet are reduced in frequency over time, and the sensation in the brain diminishes as a result.

Extending these results to the study of pain causes by the stimulus of the nervous system, he made discoveries about the reception of such signals in the brain and spatial distribution of the sensory areas of the cerebral cortex in different animals. These conclusions lead to the idea of a sensory map, called the homunculus, in the somatosensory system.

Later, Adrian used the electroencephalogram to study the electrical activity of the brain in humans. His work on the abnormalities of the Berger rhythm paved the way for subsequent investigation in epilepsy and other cerebral pathologies. He spent the last portion of his research career investigating olfaction.

Positions that he held during his career included Foulerton Professor 1929–1937; Professor of Physiology in the University of Cambridge 1937–1951; President of the Royal Society 1950–1955; Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, 1951–1965; president of the Royal Society of Medicine 1960–1962; Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1967–1975; Chancellor of the University of Leicester 1957–1971. Adrian was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society in 1938.[7][8] He was elected an International Member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1941.[9] In 1946 he became foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[10] In 1942 he was awarded membership to the Order of Merit and in 1955 was created Baron Adrian, of Cambridge in the County of Cambridge.[citation needed]

Family

On 14 June 1923 Edgar Adrian married Hester Agnes Pinsent, who was the daughter of Ellen Pinsent and sister of David Pinsent. Together they had three children, first a daughter and then twins:

- Anne Pinsent Adrian, who married the physiologist Richard Keynes, who was the great-grandson of Charles Darwin. The couple had four children.

- Adrian Keynes (1946–1974)

- Randal Keynes (*1948)

- Roger Keynes (*1951)

- Simon Keynes (*1952)

- Richard Adrian, 2nd Baron Adrian (1927–1995)

- The couple had no children.

- Jennet Adrian (b. 1927), who married Peter Watson Campbell

Bibliography

- The Basis of Sensation (1928)

- The Mechanism of Nervous Action (1932)

- Factors Determining Human Behavior (1937)

Arms

|

|

See also

- List of presidents of the Royal Society

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hodgkin, Alan (1979). "Edgar Douglas Adrian, Baron Adrian of Cambridge. 30 November 1889 – 4 August 1977". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 25: 1–73. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1979.0002. PMID 11615790.

- ↑ GRO Register of Births: DEC 1889 1a 650 HAMPSTEAD – Edgar Douglas Adrian

- ↑ GRO Register of Deaths: SEP 1977 9 0656 CAMBRIDGE – Edgar Douglas Adrian, DoB = 30 November 1889

- ↑ Raymond J. Corsini (2002). The Dictionary of Psychology. Psychology Press. pp. 1119–. ISBN 978-1-58391-328-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=0uxnglHzYaoC&pg=PA1119. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Waterston, C. D.; Shearer, A. Macmillan (2006). Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1783 – 2002: Biographical Index Part One. Royal Society of Edinburgh. p. 7. ISBN 090219884X. https://www.rse.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp1.pdf.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1932". https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1932/adrian/biographical.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. http://www.amacad.org/publications/BookofMembers/ChapterA.pdf.

- ↑ "Edgar Douglas Adrian" (in en). 2023-02-09. https://www.amacad.org/person/edgar-douglas-adrian.

- ↑ "Edgar D. Adrian". http://www.nasonline.org/member-directory/deceased-members/20001300.html.

- ↑ "Lord Edgar Douglas Adrian (1889–1977)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. http://www.dwc.knaw.nl/biografie/pmknaw/?pagetype=authorDetail&aId=PE00001665.

- ↑ Peter Townend, ed., Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, 105th edition (London, U.K.: Burke's Peerage Ltd, 1970), page 27.

- ↑ Ian Glynn (January 2011). "Richard Darwin Keynes". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 57: 205–227. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2011.0001.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage. 1959.

External links

- Miss nobel-id as parameter , accessed 1 May 2020 including the Nobel Lecture on 12 December 1932 The Activity of the Nerve Fibres

- The Master of Trinity at Trinity College, Cambridge

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Macaulay Trevelyan |

31st Master of Trinity College, Cambridge 1951–1965 |

Succeeded by The Lord Butler of Saffron Walden |

| New office | 1st Chancellor of the University of Leicester 1957–1971 |

Succeeded by Alan Lloyd Hodgkin |

| Preceded by The Lord Tedder |

Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1967–1976 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Edinburgh |

| Professional and academic associations | ||

| Preceded by Robert Robinson |

49th President of the Royal Society 1950–1955 |

Succeeded by Cyril Norman Hinshelwood |

| New creation | Baron Adrian 1955–1977 |

Succeeded by Richard Adrian |

|