Biography:Joseph Larmor

Joseph Larmor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 July 1857 Magheragall, County Antrim, Ireland, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Died | 19 May 1942 (aged 84) Holywood, County Down, Northern Ireland[1] |

| Alma mater | Royal Belfast Academical Institution Queen's University Belfast St John's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Larmor precession Larmor radius Larmor's theorem Larmor formula Relativity of simultaneity |

| Awards | Smith's Prize (1880) Senior Wrangler (1880) Fellow of the Royal Society (1892) Adams Prize (1898) Lucasian Professor of Mathematics (1903) De Morgan Medal (1914) Royal Medal (1915) Copley Medal (1921) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | St John's College, Cambridge Queen's College, Galway |

| Doctoral advisor | Edward Routh |

| Doctoral students | Kwan-ichi Terazawa |

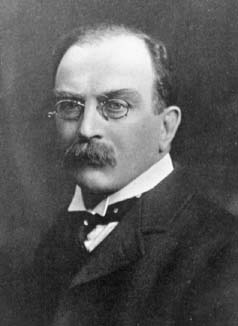

Sir Joseph Larmor FRS FRSE DCL LLD[2] (11 July 1857 – 19 May 1942) was an Irish[3] physicist and mathematician who made innovations in the understanding of electricity, dynamics, thermodynamics, and the electron theory of matter. His most influential work was Aether and Matter, a theoretical physics book published in 1900.

Biography

He was born in Magheragall in County Antrim the son of Hugh Larmor, a Belfast shopkeeper and his wife, Anna Wright.[4] The family moved to Belfast around 1860, and he was educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, and then studied mathematics and experimental science at Queen's College, Belfast (BA 1874, MA 1875),[5] where one of his teachers was John Purser. He subsequently studied at St John's College, Cambridge where in 1880 he was Senior Wrangler (J. J. Thomson was second wrangler that year) and Smith's Prizeman, getting his MA in 1883.[6] After teaching physics for a few years at Queen's College, Galway, he accepted a lectureship in mathematics at Cambridge in 1885. In 1892 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, and he served as one of the Secretaries of the society.[7] He was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1910.[8]

In 1903 he was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, a post he retained until his retirement in 1932. He never married. He was knighted by King Edward VII in 1909.

Motivated by his strong opposition to Home Rule for Ireland, in February 1911 Larmor ran for and was elected as Member of Parliament for Cambridge University (UK Parliament constituency) with the Conservative party. He remained in parliament until the 1922 general election, at which point the Irish question had been settled. Upon his retirement from Cambridge in 1932 Larmor moved back to County Down in Northern Ireland.

He received the honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D) from the University of Glasgow in June 1901.[9] He was awarded the Poncelet Prize for 1918 by the French Academy of Sciences.[10] Larmor was a Plenary Speaker in 1920 at the ICM at Strasbourg[11][12] and an Invited Speaker at the ICM in 1924 in Toronto and at the ICM in 1928 in Bologna.

He died in Holywood, County Down on 19 May 1942.[13]

Work

Larmor proposed that the aether could be represented as a homogeneous fluid medium which was perfectly incompressible and elastic. Larmor believed the aether was separate from matter. He united Lord Kelvin's model of spinning gyrostats (see Vortex theory of the atom) with this theory. Larmor held that matter consisted of particles moving in the aether. Larmor believed the source of electric charge was a "particle" (which as early as 1894 he was referring to as the electron). Larmor held that the flow of charged particles constitutes the current of conduction (but was not part of the atom). Larmor calculated the rate of energy radiation from an accelerating electron. Larmor explained the splitting of the spectral lines in a magnetic field by the oscillation of electrons.

In 1919, Larmor proposed sunspots are self-regenerative dynamo action on the Sun's surface.

Discovery of Lorentz transformation

Parallel to the development of Lorentz ether theory, Larmor published an approximation to the Lorentz transformations in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1897,[14] namely for the spatial part and for the temporal part, where and the local time . He obtained the full Lorentz transformation in 1900 by inserting into his expression of local time such that , and as before and .[15] This was done around the same time as Hendrik Lorentz (1899, 1904) and five years before Albert Einstein (1905).

Larmor however did not possess the correct velocity transformations, which include the addition of velocities law, which were later discovered by Henri Poincaré. Larmor predicted the phenomenon of time dilation, at least for orbiting electrons, by writing (Larmor 1897): "... individual electrons describe corresponding parts of their orbits in times shorter for the [rest] system in the ratio (1 – v2/c2)1/2". He also verified that the FitzGerald–Lorentz contraction (length contraction) should occur for bodies whose atoms were held together by electromagnetic forces. In his book Aether and Matter (1900), he again presented the Lorentz transformations, time dilation and length contraction (treating these as dynamic rather than kinematic effects). Larmor was opposed to the spacetime interpretation of the Lorentz transformation in special relativity because he continued to believe in an absolute aether. He was also critical of the curvature of space of general relativity, to the extent that he claimed that an absolute time was essential to astronomy (Larmor 1924, 1927).

Publications

- 1884, "Least action as the fundamental formulation in dynamics and physics", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society.

- 1887, "On the direct applications of first principles in the theory of partial differential equations", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1891, "On the theory of electrodynamics", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1892, "On the theory of electrodynamics, as affected by the nature of the mechanical stresses in excited dielectrics", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1893–97, "Dynamical Theory of the Electric and Luminiferous Medium", Proceedings of the Royal Society; Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Series of 3 papers containing Larmor's physical theory of the universe.

- 1896, "The influence of a magnetic field on radiation frequency", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1896, "On the absolute minimum of optical deviation by a prism", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

- Larmor, J. (1897). "A Dynamical Theory of the Electric and Luminiferous Medium. Part III. Relations with Material Media". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 190: 205–493. doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0020. Bibcode: 1897RSPTA.190..205L.

- 1898, "Note on the complete scheme of electrodynamic equations of a moving material medium, and electrostriction", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1898, "On the origin of magneto-optic rotation", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

- Larmor, J. (1900), Aether and Matter, Cambridge University Press; Containing the Lorentz transformations on p. 174.

- 1903, "On the electrodynamic and thermal relations of energy of magnetisation", Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1904, "On the mathematical expression of the principle of Huygens" (read 8 Jan. 1903), Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Ser. 2, vol. 1 (1904), pp. 1–13.

- 1907, "Aether" in Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. London.

- 1908, "William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs. 1824–1907" (Obituary). Proceedings of the Royal Society.

- 1921, "On the mathematical expression of the principle of Huygens — II" (read 13 Nov. 1919), Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Ser. 2, vol. 19 (1921), pp. 169–80.

- 1924, "On Editing Newton", Nature.

- 1927, "Newtonian time essential to astronomy", Nature.

- 1929, Mathematical and Physical Papers. Cambridge Univ. Press.[16]

- 1937, (as editor), Origins of Clerk Maxwell's Electric Ideas as Described in Familiar Letters to William Thomson. Cambridge University Press.[17]

Larmor edited the collected works of George Stokes, James Thomson and William Thomson.

See also

References

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Joseph Larmor", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Larmor.html.

- ↑ Eddington, A. S. (1942). "Joseph Larmor. 1857-1942". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 4 (11): 197–207. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1942.0016.

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Joseph-Larmor

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002. The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. https://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp2.pdf.

- ↑ From Ballycarrickmaddy to the moon Lisburn.com, 6 May 2011

- ↑ "Larmor, Joseph (LRMR876J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge. http://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search-2018.pl?sur=&suro=w&fir=&firo=c&cit=&cito=c&c=all&z=all&tex=LRMR876J&sye=&eye=&col=all&maxcount=50.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times (London) (36919): p. 8. 7 November 1902.

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002. The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. https://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp2.pdf.

- ↑ "Glasgow University jubilee". The Times (London) (36481): p. 10. 14 June 1901.

- ↑ "Prize Awards of the Paris Academy of Sciences for 1918". Nature 102 (2565): 334–335. 26 December 1918. doi:10.1038/102334b0. Bibcode: 1918Natur.102R.334..

- ↑ "Questions in physical indetermination by Joseph Larmor". Compte rendu du Congrès international des mathématiciens tenu à Strasbourg du 22 au 30 Septembre 1920. 1921. pp. 3–40. http://www.mathunion.org/ICM/ICM1920/Main/icm1920.0003.0040.ocr.pdf.

- ↑ H, H. B. (7 October 1920). "The International Congress of Mathematicians". Nature 106 (2658): 196–197. doi:10.1038/106196a0. Bibcode: 1920Natur.106..196H. https://books.google.com/books?id=YBJLAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA196. In his plenary address, Larmor advocated the aether theory as opposed to Einstein's general theory of relativity.

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002. The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. https://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp2.pdf.

- ↑ Larmor, Joseph (1897), "On a Dynamical Theory of the Electric and Luminiferous Medium, Part 3, Relations with material media", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 190: 205–300, doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0020, Bibcode: 1897RSPTA.190..205L

- ↑ Larmor, Joseph (1900), Aether and Matter, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Gronwall, T. H. (1930). "Review: Mathematical and Physical Papers, by Sir Joseph Larmor". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 36 (7): 470–471. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1930-04975-7. http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1930-36-07/S0002-9904-1930-04975-7/S0002-9904-1930-04975-7.pdf.

- ↑ Page, Leigh (1938). "Review: Origins of Clerk Maxwell's Electric Ideas as Described in Familiar Letters to William Thomson, by Sir Joseph Larmor". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 44 (5): 320. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1938-06738-9. http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1938-44-05/S0002-9904-1938-06738-9/S0002-9904-1938-06738-9.pdf.

Further reading

- Bruce J. Hunt (1991) The Maxwellians, Cornell University Press

- Macrossan, M. N. "A note on relativity before Einstein", British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 37 (1986): 232–234.

- Warwick, Andrew, "On the Role of the FitzGerald–Lorentz Contraction Hypothesis in the Development of Joseph Larmor's Electronic Theory of Matter". Archive for History of Exact Sciences 43 (1991): 29–91.

- Darrigol, O. (1994), "The Electron Theories of Larmor and Lorentz: A Comparative Study", Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 24 (2): 265–336, doi:10.2307/27757725

- "A very short biography of Joseph Larmor"

- "Ether and field theories in the late 19th century" At VictorianWeb: History of science in the Victorian era

- "Papers of Sir Joseph Larmor". Janus, University of Cambridge.

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Samuel Butcher John Rawlinson |

Member of Parliament for Cambridge University 1911 – 1922 With: John Rawlinson |

Succeeded by J. R. M. Butler John Rawlinson |