Biography:Sergei Bulgakov

Sergei Bulgakov | |

|---|---|

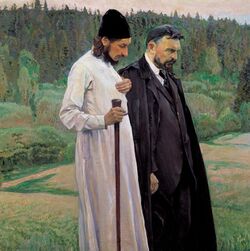

Bulgakov in the 1920s | |

| Born | Sergei Nikolayevich Bulgakov 28 July 1871 Livny, Oryol Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 12 July 1944 (aged 72) Paris, Provisional Government of the French Republic |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy |

| School | Christian philosophy Sophiology |

Main interests | Philosophy of religion |

Sergei Nikolayevich Bulgakov (Russian: Серге́й Никола́евич Булга́ков, ru; 28 July [O.S. 16 July] 1871 – 13 July 1944) was a Russian Orthodox theologian, priest, philosopher, and economist. Orthodox scholar David Bentley Hart has named Bulgakov "the greatest systematic theologian of the twentieth century."[1][2] Father Sergei Bulgakov also served as a spiritual father and confessor to Mother Maria Skobtsova (who was canonized a saint by the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate on 16 January 2004).[3] Sergei Bulgakov is best known for his development of a theological system centered on Sophia, the Wisdom of God.

Biography

Early life: 1871–1889

Sergei Nikolayevich Bulgakov was born on 16 July 1871 to the family of a rural Orthodox priest (Nikolai Bulgakov) in the town of Livny, Oryol Governorate, in Russia.[4] The family produced Orthodox priests for six generations, beginning in the sixteenth century with their ancestor Bulgak, a Tatar from whom the family name derives.[5][6][7] Metropolitan Macarius Bulgakov (1816–1882), one of the major Eastern Orthodox theologians of his days, and one of the most important Russian church historians, was a distant relative.[8]

In 1884, Bulgakov graduated from the Livny Theological School. At the age of fourteen, Bulgakov entered the Oryol Theological Seminary. In 1888, however, Bulgakov quit the seminary after a loss of his faith. In the same year, he attempted suicide. Bulgakov later noted that his passion for priesthood waned as he grew disenchanted with Orthodoxy because his teachers were unable to answer his questions.[9] After Bulgakov quit the seminary, he entered Yelets Classical Gymnasium to prepare for the law faculty of the Imperial Moscow University. Among his teachers there was Vasily Rozanov.[4]

Legal Marxism: 1890–1897

In 1890, Bulgakov entered the Imperial Moscow University where he chose to study political economy and law. As he reflected years later, however, literature and philosophy were his natural inclination and he had no interest in law. Bulgakov only chose to study law because it seemed more likely to contribute to his country's redemption.[10] After his graduation from the Law Faculty of Moscow State University (ru) in 1894, he began graduate studies at the university and taught for two years at the Moscow Commercial Institute. It was during his graduate studies when Bulgakov studied with the economist Alexander Chuprov, on whose recommendation Bulgakov was retained at the Department of Political Economy of Statistics to prepare for the professorship. Bulgakov's thought during his studies with Chuprov has generally been seen through the lens of the Marxist-Populist debate. From this perspective, he has been labeled a "legal Marxist."[4][11]

In 1895, Bulgakov began teaching political economy at the Imperial Moscow Technical School (ru).[4] In the same year, he published a review of Karl Marx's unfinished third volume of Das Kapital, and authored an essay in 1896, "On the Regularity of Social Phenomena." In the following year, Bulgakov published a study "On Markets in Capitalist Conditions of Production." It was these writings that originally established Bulgakov as a significant representative of Marxism in Russia. During his years as a legal Marxist, he had met with Karl Kautsky, August Bebel, Victor Adler, and Georgi Plekhanov.

From Marxism to Idealism: 1898–1902

On 14 January 1898, shortly before embarking for Western Europe, Bulgakov married Yelena Tokmakova, with whom he had two sons and a daughter.[12] Yelena was the daughter of Ivan Tokmakov (ru), owner of the Oleiz estate (ru) in Crimea.

In 1898, Bulgakov received a scholarship for a two-year internship in Western Europe. He left for Germany, where he tested the results of his research in personal correspondence with representatives of German Social Democracy. The result of his research was a two-volume dissertation, Capitalism and Agriculture, released in 1900. The dissertation was intended to test the application of Marx's theory of capitalist societies to agriculture. Bulgakov examined the entire agricultural history of Germany, the United States, Ireland, France, and England. The thesis ended by declaring that Marx's analysis of capitalism, limited by features of the English economy, did not integrate this system with an economic theory of agriculture, and was not a realistic, universal account of capitalist society. Originally intended to be defended as a doctoral dissertation, the work did not receive the highest rating from the Academic Council of Moscow University and was defended as a master's thesis.

In 1900 Bulgakov presented his finished dissertation for examination. It was this examination that led Bulgakov to being a privatdozent at the Kiev University of St. Vladimir and Professor of Political Economy at the Kiev Polytechnic Institute in 1901.[4] It was evident in lectures such as "Ivan Karamazov as a philosophical type" delivered in Kiev that Bulgakov had already distanced himself from Marxism. At the time of Bulgakov teaching about Dostoevsky, the counterweight to Marxism in 20th century Russia was neo-Kantianism; heavily influenced by neo-Kantianism, Bulgakov returned to idealism and believed in the significance of the historical role of the valuese of goodness and beauty. However, it was the philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov, who he began to read in 1902, that Bulgakov considered to be the highest synthesis of philosophical thought; this philosophy considered the vital principle of Christianity to be the organizing principle of social creativity. Bulgakov's idealism eventually led him back to the Eastern Orthodox Church. Bulgakov presented the individual stages of his philosophical development in his collection From Marxism to Idealism, published in Saint Petersburg in 1903.

Political turmoil: 1903–1909

Together with Pyotr Struve, Bulgakov published the journal Liberation; together, they were co-founders of the illegal political organization Union of Liberation in 1903. After the Revolution of 1905, its members formed the Constitutional Democratic (Kadet) Party, which held the most seats in the representative assemblies, the First and Second Dumas (1906–1907). Bulgakov did not join the Kadets and instead unsuccessfully attempted to form his own organization, the Union of Christian Politics, which advocated Christian socialism and collaborated with the Christian Brotherhood of Struggle.

Amidst the chaos of 1905, Bulgakov made the acquaintance of Pavel Florensky (1882–1937), with whom he would establish a long-lasting friendship. Bulgakov and Florensky were among founding members of the Vladimir Solovyov Memorial Religious-Philosophical Society, which was founded in Moscow at the end of 1905.

In 1905 Bulgakov, along with the Brotherhood of Christian Struggle, bishops, priests, and many others, supported the call for a council of the Orthodox Church in support of social reforms. In 1906, a preconciliar commission prepared six volumes of information for the council. Nicholas II thwarted the planned council, but the information would be put to use when it eventually did convene eleven years later.

In 1906, Bulgakov was editor of the Kiev newspaper Narod. After its closure, he returned from Kiev to Moscow. He taught at Moscow University as a privatdozent in the department of political economy and statistics of the Law Faculty, and was also professor at the Moscow Commercial Institute until 1918.

He was elected to the Second State Duma in 1906 as a non-partisan "Christian socialist" deputy from the Oryol Governorate. In June 1907, the Second State Duma dissolved after barely five months in session.

After the dissolution of the Second State Duma, Bulgakov lost what remaining zeal he had for direct political involvement. Another major factor in his eventual separation from the Union of Liberation was the increasingly anti-Christian direction being championed by leading representatives of left-liberal politics.

During 1904–1909, his focus shifted to an explicitly Christian perspective. Bulgakov also changed his attitude towards the controversial Nicholas II. He believed Nicholas II was responsible for the social problems plaguing Russia. However, Bulgakov also did not appreciate the increasing radicalization of the leftists in Russia and their abandonment of Russian Orthodoxy in favor of a purely secular state; on the contrary, it caused him to uphold the positive value of governance by Nicholas II, even as he continued to detest him, accusing him of promoting the revolution and bringing about the demise of the royal family. Bulgakov continued to struggle with the meaning of political power as he wrote Unfading Light.

In the summer of 1909, Bulgakov's four-year-old son Ivan died. At the funeral, Bulgakov had a profound religious experience that is generally regarded as his final step in his journey back to Orthodoxy.[13] Bulgakov would later contemplate the meaning of death in his later works, including Unfading Light.

Academia and journalism: 1910–1917

In 1911, Bulgakov left the Moscow University among a large group of liberal-minded university teachers in protest against the policies of the Minister of Public Education Lev Kasso. The following years were the period of Bulgakov's greatest social and journalistic activity. He participated in many endeavors that marked a religious and philosophical revival, such as the journals Novy put' and Voprosy religii, the collections Questions of Religion, About Vladimir Solovyov, On the Religion of Leo Tolstoy, Problems of Idealism, and Milestones, the works Religion of the Vladimir Solovyov Memorial Philosophical Society, and the publishing house Put', where the most important works of Russian religious thought were published in 1911-1917. In his work during this period, he transitioned from lectures and articles on topics of religion and culture (the most important of which he collected in the two-volume book Two Cities, published 1911) to original philosophical developments.

In 1911, Bulgakov was elected fellow chairman of the Alexander Chuprov Society for the Development of Social Sciences (ru) and a member of the Commission on Church Law at the Moscow Law Society.

In 1913, Bulgakov defended his doctoral dissertation on political economy, Philosophy of Economics, at Moscow University, in which he put forward Christianity as a universal process, the subject of which is Sophia - the world soul, creative nature, ideal humanity. He was elected full professor of political economy at Moscow University.[4]

In 1917, Bulgakov became a delegate of the All-Russian Congress of Clergy and Laity and a member of the All-Russian Local Council of the Orthodox Russian Church, the Religious and Educational Conference under the Cathedral Council, the Commission for Familiarization with the Financial Situation of the Council, and the VI, VII, IX, and XX Departments. He was an author of the Patriarchal Message on Accession to the Throne. From December 1917, he was a member of the Supreme Church Council of the Russian Orthodox Church (ru).

Priesthood and October Revolution: 1917–1921

In June 1918, Bulgakov was ordained a deacon and then a priest. He quickly rose to prominence in church circles. He took part in the All-Russia Sobor of the Russian Orthodox Church that elected patriarch Tikhon of Moscow. Bulgakov rejected the October Revolution and responded to it with the dialogues At the Feast of the Gods ("На пиру богов", 1918), written in a style similar to the Three Talks of Vladimir Solovyov.

In July 1918, Bulgakov left Moscow, first going to Kiev then joining his wife and children in Koreiz in Crimea. For the next two years, he was a member of the Tauride Diocesan Council in Simferopol and a professor of political economy and theology at the Tauride University in Simferopol. In the works Philosophy of the Name (written in 1920, published in 1953) and The Tragedy of Philosophy (written in 1920, published in 1928), written at that time, he revised his view of the relationship between philosophy and dogmatics of Christianity, coming to the conclusion that Christian speculation can be expressed without distortion exclusively in the form of dogmatic theology. When the Bolsheviks captured Crimea in 1920, Bulgakov was dismissed from his teaching position at the university.

In 1921, Bulgakov became archpriest and assistant rector of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Yalta. In September 1922, he was arrested on charges of political unreliability.[4]

Emigration to Prague: 1922-1924

In 1922, Bulgakov was included in a list of scientific and cultural figures subject to deportation, compiled by the State Political Directorate on the initiative of Vladimir Lenin. On 30 December 1922, he was deported to Constantinople on one of the so-called philosophers' ships without the right to return to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. After a short stay in Constantinople, he arrived in Prague. In May 1923, with the blessing of Metropolitan Eulogius Georgiyevsky, he served in Prague's St. Nicholas Cathedral and took the position of professor in the department of church law and theology at the Law Faculty of the Russian Scientific Institute (ru) in Berlin.[14]

Bulgakov involved himself in the spiritual leadership of Russian youth and participated in the ecumenical movement. He was founder and leader of the Brotherhood of St. Sophia (ru), created with the blessing of Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow,[15] and an organizer and participant in the congresses of the Russian Student Christian Movement (ru) (RSCM). He participated in the first congresses of the RSCM in Přerov, Czechoslovakia and Argeron, France, and continued to supervise it.

Paris: 1925-1944

In July 1925, Bulgakov moved to Paris. He was a member of the Committee for the Construction of the Sergius Metochion and an assistant to its organizer. He helped found the St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute (l'Institut de Théologie Orthodoxe Saint-Serge), where he worked until his death.[14] He taught courses on "Holy Scripture of the Old Testament" and "Dogmatic Theology".[16]

Bulgakov became involved in the work of the ecumenical movement in 1927 at the World Christian Conference "Faith and Church Order" in Lausanne. Until the end of the 1930s, he took part in many ecumenical endeavors, becoming an influential figure and ideologue of the movement; in 1934 he made a trip to the United States. The most promising direction in the ecumenical sphere turned out to be Orthodox-Anglican dialogue (ru) with the Anglican Church. At the end of 1927 and beginning of 1928, an Anglo-Russian religious congress was held, which resulted in the establishment of the bilateral Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius.

While living in Paris, he completed two dogmatic trilogies on Sophiology — the first, The Burning Bush (1926), The Friend of the Bridegroom (1927), Jacob’s Ladder (1929); the second, The Lamb of God, The Comforter, The Bride of the Lamb (1939). It is in The Bride of the Lamb that Bulgakov argues for apokatastasis. Bulgakov states that humankind will "ultimately be justified." He also argues in this book for a supramundane fall, saying that "empirical history begins precisely with the fall, which is its starting premise."[17]

In 1935, after the publication of his book, Lamb of God, Bulgakov was accused of teachings contrary to Orthodox dogma by the Metropolitan Sergius I of Moscow, who recommended his exclusion from the Church until he amended his "dangerous" views. The Karlovtsy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia also joined in this condemnation. Metropolitan Evlogy set up a committee in Paris to investigate Bulgakov's orthodoxy, which reached a preliminary conclusion that his thought was free from heresy. However, an official conclusion was never reached.

In 1939, Bulgakov was diagnosed with throat cancer. He underwent surgery, after which he learned to speak without vocal cords. He served early liturgies in the chapel in the name of the Dormition of the Mother of God, and continued to lecture on dogmatic theology, carry out his pastoral care, and write. Although the outbreak of World War II limited Bulgakov, he did not stop working on new works and performing services. In 1943, he was awarded a miter.

In occupied Paris, he wrote the work Racism and Christianity, debunking the ideology of fascism. He finished his last book, The Apocalypse of John, shortly before his death. On the night of 5-6 June 1944, he had a stroke, after which he remained unconscious for forty days. He died on 13 July 1944. He was buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery in the southern suburbs of Paris.

Selected works

- Bulgakov, Sergei (1899). A Contribution to the Question of the Capitalist Evolution of Agriculture. Published in nos. 1–3 of the magazine Nachalo in January–March 1899.

- ——— (1944). Father Sergius Bulgakov, 1871-1944 : a collection of articles by Fr. Bulgakov for the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius and now reproduced by the Fellowship to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the death of this great ecumenist. London: Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius. OCLC 718257515.

- ——— (1988). The Orthodox Church. Crestwood, N.Y: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 195. ISBN 0-88141-051-9.

- ——— (1993). Sophia, the Wisdom of God. Hudson, N.Y: SteinerBooks. pp. 155. ISBN 978-0-940262-60-7.

- ——— Reitlinger, Ioanna (1995). Apocatastasis and Transfiguration. ISBN 978-1-929829-01-9.

- ——— (1997). The Holy Grail and the Eucharist. Hudson, N.Y: SteinerBooks. pp. 156. ISBN 0-940262-81-9.

- ——— (1999-01-01). Sergii Bulgakov. Edinburgh: A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-08685-3.

- ——— (2000). Philosophy of Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07990-6. https://archive.org/details/philosophyofecon00bulg.

- ——— (2002-02-14). Bride of the Lamb. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 531. ISBN 0-567-08871-5.

- ——— (2003). The Friend of the Bridegroom. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 190. ISBN 0-8028-4979-2.

- ——— (2004-06-09). The Comforter. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 398. ISBN 0-8028-2112-X.

- ——— (2008-01-02). The Lamb of God. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 531. ISBN 0-8028-2779-9.

- ——— (2008-03-18). Churchly Joy. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 147. ISBN 978-0-8028-4834-5.

- ——— (2009-04-10). The Burning Bush. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 191. ISBN 978-0-8028-4574-0.

- ——— (2010-11-16). Jacob's Ladder. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6516-8.

- ——— (2011-09-02). Relics and Miracles. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6531-1.

- ——— (2012-02-27). Icons and The Name of God. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6664-6.

- ——— (2012-08-01). Sergius Bulgakov. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-4982-6465-5.

- ——— (2012-12-12). Unfading Light. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6711-7.

Political views

Template:Christian socialism sidebar Bulgakov condemned the basic view of political economy of the early 20th century, according to which the growth of material needs is the fundamental principle of normal economic development. He viewed economic progress as a necessary condition for spiritual success, but warned against the inclination to replace universal human and cultural progress with economic progress alone. To him, moral materialism and spiritual bourgeoisness, which once destroyed the Roman civilization, were a disease of modern European society. Bulgakov viewed the inability to be satisfied with the increase in external material benefits and to come to terms with the deep-rooted forms of social untruth, the desire for universal human ideals, and the insatiable need for conscious and effective religious faith as the most characteristic and happiest features of the Russian spirit. This conviction of his was revealed in his public lectures and in his article "Carlyle and Tolstoy" (Novy Put, December 1904). Being a direct student of Vladimir Solovyov in his philosophical convictions, Bulgakov, however, was critical of his church-political and economic program.

In his extensive dissertation, the two-volume book Capitalism and Agriculture, Bulgakov questioned the effect of the law of concentration of production in agriculture, examined the advantages of small peasant farms over large ones, analyzed the reasons for the stability of family farming, and came up with a distributive version of the source of land rent. He set out to show in the history of agrarian evolution the universal applicability of Karl Marx's law of concentration of production, but came to the exact opposite conclusions. To Bulgakov, Marx's economic scheme turned out to be inconsistent with historical reality, and the positive theory of social progress associated with it was unable to nourish man's ineradicable faith in the historical justification of the good.

After unsuccessful attempts to use Kant's epistemological precepts in the interests of Marxism, Bulgakov settled on the idea that a solid justification for the guiding principles of personal and public life is possible only by developing unconditional standards in matters of the good, the truth, and beauty. To him, positive science, with its theory of progress, wanted to absorb both metaphysics and religious faith, but, leaving people in complete uncertainty regarding the future destinies of humanity, it gave them only the dogmatic theology of atheism; a mechanical understanding of the world, subordinating everything to fatal necessity, ultimately turns out to rest on faith. For Bulgakov, Marxism, as the brightest variety of the religion of progress, inspired its supporters with faith in the imminent and natural arrival of a renewed social system; it was strong not in its scientific, but in its utopian elements, and Bulgakov came to the conviction that progress is not an empirical law of historical development, but a moral task, an absolute religious obligation. Social struggle appeared to Bulgakov not as a clash of merely hostile class interests, but as the implementation and development of a moral idea. "Is" cannot justify "ought"; the ideal cannot follow from reality.

According to Bulgakov, the doctrine of class egoism and class solidarity is imprinted by the nature of superficial hedonism. From a moral point of view, parties fighting over worldly goods are quite equivalent, since they are guided not by religious enthusiasm, not by the search for the unconditional and lasting meaning of life, but by ordinary self-love. According to Bulgakov, the eudaimonic ideal of progress, as a scale for assessing historical development, leads to antimoral conclusions, to the recognition of suffering generations as only a bridge to the future bliss of their descendants.

Bulgakov's work as a priest began with journalism, articles on economic, socio-cultural, and religious-philosophical topics. Bulgakov's journalism came to the fore at critical moments: the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the beginning of the First World War in 1917. A number of significant themes of Bulgakov's thought developed almost exclusively in journalism: religion and culture, Christianity, politics and socialism, the tasks of the public, the path of the Russian intelligentsia, problems of church life, and problems of art.

Bulgakov was one of the main exponents of vekhovstvo, an ideological movement that called on the intelligentsia to "sober up" and move away from "herd morality", "utopianism", and "rabid revolutionism" in favor of the work of spiritual comprehension and a constructive social position. During the same period, he developed on his ideas of socialist Christianity, producing an analysis of the Christian attitude to economics and politics (with an apology for socialism, which was gradually declining), criticism of Marxism and bourgeois-capitalist ideology, projects for a "party of Christian politics," and responses to the issues of the day (from the standpoint of Christian liberal-conservative centrism). The theme of Russia was a special focus, and was addressed, following Dostoevsky and Solovyov, along the paths of Christian historiosophy.

Bulgakov's views changed greatly in response to the issues in Russia. At the beginning of the First World War, he wrote Slavophile articles and expressed faith in the universal calling and great future of the state. Later, in the dialogues At the Feast of the Gods and other texts of the revolutionary period, he depicted the fate of Russia as apocalyptic and alarmingly unpredictable, rejecting any recipes and forecasts. For a short time, Bulgakov believed that Catholicism rather than Orthodoxy would be able to prevent the processes of schism and disintegration that prepared the catastrophe of the nation. Later, he was engaged in the creation of Christian economic theory,[18] and his journalism focused only on church and religious-cultural topics.[19]

Philosophical ideas

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Bulgakov became disillusioned with Marxism because he considered it incapable of answering the deep religious needs of the human personality and radically changing it. He returned to Christianity. In the 1905 Revolution, he wrote an article titled "Heroism and Asceticism",[20] in which he spoke about the "two paths" for the Russian intelligentsia. Heroism was the path followed by the majority; this path is an attempt to change society by external means, replacing one class with another, and using violence and terror with complete disregard for the spiritual and moral content of one's own personality. Asceticism is a different path, which presupposes a transformation of one’s own personality. This path requires not external, but internal feat. He warned that the path of heroism would lead Russia to a bloody tragedy.

With his theology, Bulgakov, as Father Sergius, provoked accusations from the Moscow and Karlovci jurisdictions of the Orthodox Church. The conflict had both political and theological reasons. The church-political background of the conflict was expressed in the confrontation between the Karlovci (pro-monarchist) and Moscow (under severe pressure from Stalin) churches of the free Exarchate of Parishes of the Russian Tradition in Western Europe (ru), which since 1931 was subordinate to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. In the field of theology, the fear of posing new theological questions made itself felt. In 1935, Bulgakov's teaching was condemned in the decrees of the Moscow Patriarchate, and in 1937, also by the foreign Council of Bishops in Karlovci. However, the commission of professors of the St. Sergius Institute and the diocesan commission (1936), convened by Metropolitan Eulogius Georgiyevsky, rejected all accusations of heresy.

Bulgakov was influenced by Rudolf Steiner.[21]

Sophiology

In polemics with the tradition of German idealism, Bulgakov refuses to consider reason and thinking as the highest principle, endowed with the exclusive prerogative of connection with God. The justification of the world thus presupposes the justification of matter, and Bulgakov sometimes defined the type of his philosophical worldview by the "religious materialism" of Vladimir Solovyov. Father Sergius's thought developed "from below", from economic issues and philosophical teaching on the economy (Philosophy of Economy) to a general teaching on matter and the world, and, finally, to a comprehensive theological system that provides a final solution to the original problem: rooting the world in God and at the same time directly following Christian revelation and dogma.[19]

Bulgakov says that God created the world from His own essence, placed outside of Himself. Here Father Sergius resorts to the biblical concept of Sophia - the wisdom of God, which is identical to nature, the ousia of God. And this Divine Sophia, placed outside of Itself by the creative act of God, becomes the created Sophia and is the basis of the created world. Its createdness lies in its position during time and becoming. The created Sophia is manifested in the potentials of being, which, like seeds sown in the earth, must sprout, but the possibility of their sprouting and the quality of growth are directly related to the self-determination and activity of man - the hypostasis of the created Sophia. "Earth" and "mother" are the key definitions of matter for Bulgakov, expressing its conceiving and birthing power, its fruitfulness. The earth is "saturated with limitless possibilities"; it is "all-matter, for everything is potentially contained in it" (The Unfading Light (ru). Moscow, 1917, pp. 240-241). Although after God, by His will, matter is also a creative principle. Mother Earth does not simply give birth, but brings forth from its depths all that exists. At the height of its generative and creative effort, in its utmost tension and utmost purity, it is potentially "God-earth" and the Mother of God. Mary comes from its depths and the earth becomes ready to accept the Logos and give birth to the God-man. The earth becomes the Mother of God and only in this is the true apotheosis of matter, the rise and crowning of its creative effort. Here is the key to all of Bulgakov's "religious materialism."[19]

Bulgakov also explores the philosophical foundations of language in another book of the same period, The Philosophy of the Name, dedicated to the apology of imiaslavie and related to similar apologies by Florensky and Losev. From this correspondence, a classification of philosophical systems is derived, allowing us to see in their main types various monistic distortions of the dogma of the trinity, which excludes monism and requires complete equality, consubstantiality of the three principles, united in an elementary statement ("I am the existing") and understood as ontological principles. As a result, the history of philosophy appears as the history of a special kind of Trinitarian heresy. Bulgakov concludes that an adequate expression of Christian truth is fundamentally inaccessible to philosophy and is achievable only in the form of dogmatic theology.[19]

See also

- Eastern Orthodox Christian theology

- Imiaslavie

- Liberation theology

- List of Russian philosophers

- Political theology

- Theophilus of Antioch

References

- ↑ "David Bentley Hart: 'Orthodoxy in America and America's Orthodoxies'". 2 October 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WU3y_h47ByE. ""At minute marker 32:51.""

- ↑ "The Genius of Sergei Bulgakov - David Bentley Hart". 19 June 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mf7f2WIE2i8.

- ↑ "Synaxis of Saint Maria Skobtsova of Paris and Her Companions (+ 1945)". 20 July 2017. https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2009/08/saint-maria-skobtsova-of-paris-and-her.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 ROSSPEN 2010, p. 101.

- ↑ George Vernadsky, The Mongols and Russia, Yale University Press (1943), p. 384

- ↑ Catherine Evtuhov, The Cross & the Sickle: Sergei Bulgakov and the Fate of Russian Religious Philosophy, Cornell University Press (1997), p. 23

- ↑ Judith Deutsch Kornblatt & Richard F. Gustafson, Russian Religious Thought, Univ of Wisconsin Press (1996), p. 135

- ↑ Rowan Williams, "General introduction" in Sergii Nikolaevich Bulgakov, Sergii Bulgakov: Towards a Russian Political Theology, A&C Black (1999), p. 3

- ↑ Sergei Bulgakov, A Bulgakov Anthology, Wipf & Stock (2012), p. 3

- ↑ Sergei Bulgakov, A Bulgakov Anthology, Wipf & Stock (2012), p. 4

- ↑ See especially the biography of Bulgakov in Richard Kindersley, The First Russian Revisionists: A Study of "Legal Marxism" in Russia. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962; pp. 59–63.

- ↑ Russian Religious Thought edited by Judith Deutsch Kornblatt and Richard F. Gustafson. Univ of Wisconsin Press (1996). p.135

- ↑ Sergei Bulgakov, Unfading Light: Contemplations and Speculations, Eerdmans (2012), p. xxv

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 ROSSPEN 2010, p. 102.

- ↑ Struve, N. A. (2000) (in ru). Братство Святой Софии. Moscow: Russky put'. ISBN 5-85887-077-5.

- ↑ "Островок преподобного Сергия посреди парижского моря. Беседа с протоиереем Николаем Озолиным, инспектором Свято-Сергиевского богословского института" (in ru). 2013-03-17. http://pravoslavie.ru/32208.html.

- ↑ Bulgakov, Sergei (2001). "Evil". The Bride of the Lamb. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 170–172. ISBN 9780802839152.

- ↑ Chayanov, Alexander (1989) (in ru). Крестьянское хозяйство. Moscow: Ekonomika. ISBN 978-5-282-00835-7.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Abramov, A. I. (1995) (in ru). Русская философия. Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 5-02-013025-7.

- ↑ Bulgakov, Sergei. "Героизм и Подвижничество" (in ru). https://www.vehi.net/vehi/bulgakov.html.

- ↑ Russell, Norman (2024). Theosis and Religion: Participation in Divine Life in the Eastern and Western Traditions. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-108-31101-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=mDX9EAAAQBAJ&dq=Rudolf+Steiner+religion&pg=PA24. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

Further reading

- R. Williams, Sergii Bulgakov: Towards a Russian Political Theology (1999) Continuum.

- N. Zernov, The Russian Religious Renaissance of the Twentieth Century (1963)

- L. Zander, God and the world (2 vols. 1948) [Russian text] (a survey of Bulgakov's thought)

- (in ru) Императорский Московский университет, 1755-1917: Энциклопедический словарь.. Moscow: ROSSPEN. 2010. ISBN 978-5-8243-1429-8.

- Paul Valliere, "Modern Russian Theology: Bukharev, Solovyov, Bulgakov : Orthodox theology in a new key." (2000) Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Robert F. Slesinksi, "The Theology of Sergius Bulgakov" (2017) New York: St Vladimir's Seminary Press

- Brandon Gallaher, "Freedom and Necessity in Modern Trinitarian Theology" Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press [on Sergii Bulgakov, Karl Barth, and Hans Urs von Balthasar]

- Walter N. Sisto, "The Mother of God in the Theology of Sergius Bulgakov. The Soul of the World." (2017) London: Routledge.

- Mikhail Sergeev, "Sophiology in Russian Orthodoxy: Solov'ev, Bulgakov, Losskii, and Berdiaev." (2006) Lewiston N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Catherine Evtuhov, "The cross and the sickle. Sergei Bulgakov and the fate of Russian religious philosophy." (1997) Ithaca etc.: Cornell University Press.

- Sergij Bulgakov, "Bibliographie. Werke, Briefwechsel und Übersetzungen" (B. Hallensleben & R. Zwahlen Eds. Vol. 3). (2017) Münster: Aschendorff Verlag. (Bibliography with Russian titles and German translation.)

- Barbara Hallensleben, Regula M. Zwahlen, Aristotle Papanikolaou, Pantelis Kalaitzidis (Hrsg.): Building the House of Wisdom. Sergij Bulgakov and Contemporary Theology. New Approaches and Interpretations. Aschendorff, Münster 2024 (open access)

External links

- Works by Sergei Bulgakov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sergei Bulgakov (in Russian)

- «Unfading Light» (in Russian)

- Sergius Bulgakov Society – Extensive collection of links to Bulgakov resources

- – Sergij Bulgakov Research Center; List of English translations including pdf-downloads

- Forschungsstelle Sergij Bulgakov (dt.)

- Bulgakoviana (in Russian)

|