Biology:Aerosaurus

| Aerosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

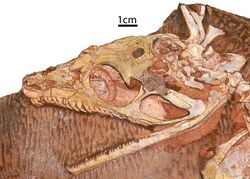

| Well-preserved partial skeleton of Aerosaurus wellesi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Family: | †Varanopidae |

| Subfamily: | †Varanopinae |

| Genus: | †Aerosaurus Romer, 1937 |

| Species | |

| |

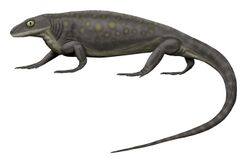

Aerosaurus (meaning "copper lizard") is an extinct genus within Varanopidae, a family of non-mammalian synapsids. It lived between 252-299 million years ago during the Early Permian in North America. The name comes from Latin aes (aeris) (combining stem: aer-) “copper” and Greek sauros “lizard,” for El Cobre Canyon (from Spanish cobre “copper”) in northern New Mexico, where the type fossil was found and the site of former copper mines. Aerosaurus was a small to medium-bodied carnivorous synapsid characterized by its recurved teeth, triangular lateral temporal fenestra, and extended teeth row. Two species are recognized: A. greenleeorum (1937) and A. wellesi (1981).[1]

History and discovery

Aerosaurus was a taxon named by American paleontologist and biologist Alfred Romer in 1937. There have only been two species named: A. greenleeorum (1937) and A. wellesi (1981), both discovered in New Mexico. A. greenleeorum Romer, 1937, is based on bone fragments assumed from a single individual collected by Romer in El Cobre Canyon near the Abo/Cutler Formation of the Arroyo del Agua. Cross-examination of the fragmentary holotype of A. greenleeorum Romer with the Camp Quarry skeleton with its expanded tooth-bearing parasphenoidal plate matches it to Aerosaurus taxa.[2]

The discovery of A. wellesi came from a team led in 1935 by Dr. Samuel P. Welles, who excavated blocks of red siltstone measuring thirty square feet in the Lower Permian Abo/Cutler Formation in near the Arroyo del Aqua settlement. The blocks of siltstone contained two incomplete skulls of Oedaleops campi Langston, 1965, and the two nearly complete articulated skeletons of a varanopseid pelycosaur.[2]

Description

Aerosaurus has been recognized as a basal member of the Synapsida, a clade that ultimately produced mammals. Relative to the skull, the body was much larger and the ribs were deeper. The tail was unusually long for a synapsid. Overall varanopseid pelycosaurs measure about one meter long with fewer maxillary and dentary teeth compared to other Varanops. In Aerosaurus, the teeth were more laterally compressed creating a strong recurved shape. Aerosaurus cranial morphology is distinguishable with its extremely long tooth row, recurved teeth, and triangular lateral temporal fenestra. The teeth were so highly curved and compressed that they may have had difficulty penetrating flesh, and the tooth row extended far behind the orbit. The lower teeth were also relatively tiny and such an arrangement suggests Aerosaurus was a carnivore. Their limbs were long, and skeleton built lightly suggests they were active and agile. A long low skull and dentition extended far back to lie below the temporal fenestra. Aerosaurus had other general features found in ‘pelycosaurs’, like a slanted occiput, a lateral temporal fenestra, a septomaxilla bone that contacting the nasal and a maxilla bone contacting the quadrojugal.[2]

Skull

The skull is 1/4 of the precaudal length of the skeleton with a jaw articulation far back seen in Varanops. The snout is long and low with an lessen inclined occiput. The dermal bones are shallow, irregular with pits and grooves and below the orbit we find a saw-like serration that hasn't been seen in other 'pelycosaurs'. The skull roof has large round orbits and an undetermined laterally expanded prefrontal process. The postorbital is incomplete, but the postorbital and suborbital bars are thinly shaped. The pineal foramen is larger compared to non-varanopseid sphenacodonts and is positioned in the back of the skull. The lateral temporal fenestra of Aerosaurus is larger than other pelycosaurs with its trademark triangular shape. No septomaxilla is evident, but the premaxilla is fragile in comparison to the large naris. The maxilla contains specimens largest teeth and is extended posterior to the center of the triangular lateral temporal fenestra. The maxilla, which is longer compared to other 'pelycosaurs' contacts the quadratojugal in this specimen. The lacrimal is a sheet of bone that covers most of the anterior orbital margin and constricts the front of the orbit.

The jugal has a unique lateral serration and narrow postorbital ramus similar to Varanops. The quadtrojugal has a slender ramus that meets the jugal and the maxilla. The nasal is also long and slender, but has extensive fragmentation, so an exact length is undetermined. The frontal is long and slender with the posterior end not extending into the margins of the orbit. The Postfrontal is small due to the size of the frontal. The squamosal is long and narrow and even more so compared to Varanops. The parietal is large with shallow grooves in the supratemporal element. The braincase is well preserved with only the cultriform process missing in all of its external surfaces. The parasphenoid is the largest part of the braincase with some overlap into the basiooccipital to form the "fenestra ovalis". The presence of the many strong, pointed, and recurved teeth is a distinguishing feature of the bottom side of the braincase. The teeth are arranged in a pattern of three groups to form a U-shaped band. There is trouble distinguishing between the basisphenoid and the parasphenoid due to the co-ossification creating a vague suture line. The basisphenoid has a large basipterygoid process that extend from the base of the cultriform process.[2]

The mandible has a long and slender shape with grooves and pits like on the skull roof. The dentary is long with a posterodorsal process that extends into the lower jaw and overlapping the surangular. The angular and prearticular bones are long with the splenial almost as long as the dentary. The coronoid was unidentifiable in this specimen. A foramen intermandibularis caudalis is on the medial surface of the mandible similar to the related Varannops and Ophiacodon species.[2]

The skull of Aerosaurus had 16 marginal teeth, less than in Varanops (44) and the upper teeth were longer. Most of the teeth were recurved more than other 'pelycosaurs' with a triangular depression near the base. The size of each teeth varied with some teeth-sized gap spaces. There largest teeth (7) were on the maxilla and decreased in length posterior to the orbit. There is additional six long recurved teeth located ventral to the postorbital bar, but the function of them are a mystery. The mandibular teeth are smaller, closely spaced, uniform in its recurved shape compared to the maxilla.[2]

Postcrania

There are twenty-six presacral vertebrae with some missing due to erosion. Around five of the anterior vertebrae could possibly be cervical and three sacral vertebrae are present in this specimen. Overall there are at least 70 caudal vertebrae making up its long slender tail, which is greater than any other 'pelycosaur'. The neural spines are shorter with a typical atlas bearing a posterior spine to pass to the zygapophyses. The axis is about the length of the other cervical vertebrae. Each vertebra is ossified with no visible suture between the centrum and neural arch. The distal caudal vertebrae is slender and cylinder shaped and is poorly preserved compared to the other portion of vertebrae.[2]

Presacral vertebrae have a slender double-headed ribs, but which rib is the longest is undetermined because of the articulation of the fossil. Some dorsal ribs are distally expanded. The Gastralia is seen in a cluster of tiny rods in some articulated ribs. Gastralia are narrow plates in other 'pelycosaurs' compared to Aerosaurus.[2]

The pectoral girdle is preserved in a medial surface with the left scapula partially exposed. The clavicle is also preserved, but no cleithrum is identifiable in this specimen. The shoulder girdle similar to Varanops with a curved scapulocoracoid. The clavicle is expanded anteroposteriorly. The T-shaped interclavicle is similar to Ophiacodon and is well preserved. The pelvic girdle is not entirely exposed in this specimen. The neck of the iliac blade is narrower compared to A. greenleeorum, but the ischium is longer and ossified. The pubis is not exposed well enough to be described. The left side of the limbs are well preserved with the humerus and femur in similar length to the lower legs. Allowing for a high posture and long strides for a predaceous mode of life. The ulna is straight, thick with a well developed olecranon. The left manus is assumed to be complete with what is visible in the fossil. Terminal phalanges have short recurved claws with a phalangeal formula of 2:3:4:5:3. The femoras are straight, thick with ends that aren't enlarged. The tibia is big and bowed shaped. The astragalus is short and square-cut without a long proximal neck.[2]

Paleobiology

A. wellesi had a humerus and femur in similar length to the lower legs, which allowed it to have a high posture and long strides for a predaceous or carnivorous type of life. The ossified feet and exceedingly long tail of Aerosaurus suggests an agile terrestrial carnivore[2] ‘Pelycosaurs’ represent first group to dominate the terrestrial fauna and achieve large body size at a time where the supercontinent Pangea existed. The discovery of Pyozia mesenensis from the Middle Permian suggests there was an adaptation to ecological and climate changes that occurs into the late Paleozoic. Varanopid tended to be small to medium-sized basal 'pelycosaurs' that were carnivores and coexisted with herbivory animals in this landscape. The P. mesenensis discovery is just an increasing trend of a “mammalness” trait during the introduction of herbivory prey that appears during the Permian.[3]

Thermoregulation

Members of 'pelycosaurs' were most likely ectothermic with some theories with Edaphosauridae and Dimetrodon using their sail structure to preserve heat. Ectothermic animals like reptiles and 'pelycosaurs' needed to maintain a level of body temperature versus the external environment in order to survive. It is estimated that the 'pelycosaur' would need to stay within the range of 24 to 35 degrees Celsius similar to modern reptiles. This is backed up by the location of 'pelycosaur discoveries in the regions of warmer temperatures in the supercontinent of Pangea in now known localities in New Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma to name a few. A change in color, respiration, blood flow and metabolism are some of the ways reptiles today regulate their body temperature and could be some of the ways 'pelycosaurs' could evolve to expand their niches.[4]

Paleoecology

The 'pelycosaurs' and Aerosaurus would have lived in the super continent Pangaea. The northern and southern hemisphere during the Early Permian was hot and arid with evaporite deposits in North America and Europe. The southernmost and Northernmost continents of Pangaea had a cold and temperate climate. The equator of Pangaea would have a tropical and humid climate. The flora would change from the tropical forests of the Carboniferous to be replaced by seed-bearing plants like conifers during the Early Permian. The most discoveries from the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian tetrapods were in the Northern Hemisphere. Discoveries of fossil tetrapods from the Middle and Late Permian were from South Africa and Russia creating a temporal gap. A temporal gap between the fossil records of the Early and Middle Permian or the Olson's Gap, after Everett C. Olson, a well known vertebrate paleontologist was closed with redating Permian fossil beds and newer fossil discoveries. Aerosaurus would be found in red siltstone in the Abo/Cutler Formation in New Mexico, so it existed within an open and arid environment.[5]

Classification

Aerosaurus belongs in the extinct family Varanopidae, grouped among the "pelycosaurs" or "mammal-like reptiles"; they became extinct around the end of the Permian. Within the Varanopidae are the subfamilies Mycterosaurinae and Varanopinae; Aerosaurus belongs to the Varanopinae in this phylogeny. Elliotsmithia longiceps is placed in the Mycterosaurinae. The sister family of Varanopidae is Ophiacontidae.[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Romer, A. S. (1937). "New Genera and Species of Pelycosaurian Reptiles". Proceedings of the New England Zoölogical Club 16: 90–96. http://www.stuartsumida.com/BIOL680-09/Romer1937.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Langston, W.; Reisz, R. (1981). "Aerosaurus wellesi, new species, a varanopseid mammal-like reptile (Synapsida : Pelycosauria) from the Lower Permian of New Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 1 (1): 73–96. doi:10.1080/02724634.1981.10011881.

- ↑ Anderson, J.; Reisz, R. (2004). "Pyozia mesenensis, a new, small varanopid (Synapsida, Eupelycosauria) from Russia: "pelycosaur" diversity in the Middle Permian". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (1): 173–179. doi:10.1671/1940-13.

- ↑ Florides, G. A.; Wrobel, L. C.; Kalogirou, S. A.; Tassou, S. (1999). "A thermal model for reptiles and pelycosaurs". Journal of Thermal Biology 24 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/S0306-4565(98)00032-1.

- ↑ Benton, M.; Sibbick, J. (2015). Vertebrate palaeontology (4 ed.). West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-40755-4.[page needed]

- ↑ Modesto, S.; Sidor, C.; Rubidge, B.; Welman, J. (2001). "A Second Varanopseid Skull from the Upper Permian of South Africa: Implications for Late Permian 'Pelycosaur' Evolution". Lethaia 34 (4): 249–259. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2001.tb00053.x.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q3278942 entry

|