Biology:Bartonella

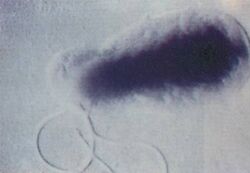

Bartonella is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria. It is the only genus in the family Bartonellaceae.[2][3] Facultative intracellular parasites, Bartonella species can infect healthy people, but are considered especially important as opportunistic pathogens.[4] Bartonella species are transmitted by vectors such as fleas, sand flies, and mosquitoes. At least eight Bartonella species or subspecies are known to infect humans.[5]

Bartonella henselae is the organism responsible for cat scratch disease.

History

Bartonella species have been infecting humans for thousands of years, as demonstrated by Bartonella quintana DNA in a 4000-year-old tooth.[6] The genus is named for Alberto Leonardo Barton Thompson (1871–October 26, 1950), a Peruvian scientist.[7]

Infection cycle

The currently accepted model explaining the infection cycle holds that the transmitting vectors are blood-sucking arthropods and the reservoir hosts are mammals. Immediately after infection, the bacteria colonize a primary niche, the endothelial cells. Every five days, some of the Bartonella bacteria in the endothelial cells are released into the blood stream, where they infect erythrocytes. The bacteria then invade a phagosomal membrane inside the erythrocytes, where they multiply until they reach a critical population density. At this point, they simply wait until they are taken up with the erythrocytes by a blood-sucking arthropod.[citation needed]

Though some studies have found "no definitive evidence of transmission by a tick to a vertebrate host,"[8][9] Bartonella species are well-known to be transmissible to both animals and humans through various other vectors, such as fleas, lice, and sand flies.[10] Bartonella bacteria are associated with cat-scratch disease, but a study in 2010 concluded, "Clinicians should be aware that ... a history of an animal scratch or bite is not necessary for disease transmission."[11] All current Bartonella species identified in canines are human pathogens.[12]

Pathophysiology

Bartonella infections are remarkable in the wide range of symptoms they can produce. The course of the diseases (acute or chronic) and the underlying pathologies are highly variable.[13]

| Bartonella pathophysiology in humans | ||||

| Species | Human reservoir or incidental host? |

Animal reservoir |

Pathophysiology | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. bacilliformis | Reservoir | Causes Carrion's disease (Oroya fever, Verruga peruana) | Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia | |

| B. quintana | Reservoir | Japanese macaque | Causes trench fever, bacillary angiomatosis, and endocarditis | Worldwide |

| B. clarridgeiae | Incidental | Domestic cat | Cat scratch disease | |

| B. elizabethae | Incidental | Rat | Endocarditis | |

| B. grahamii | Incidental | Mouse | Endocarditis and neuroretinitis | |

| B. henselae | Incidental | Domestic cat | Cat scratch disease, bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatis, endocarditis, bacteremia with fever, neuroretinitis, meningitis, encephalitis | Worldwide |

| B. koehlerae | Incidental | Domestic cat | ||

| B. naantaliensis | Reservoir | Myotis daubentonii | ||

| B. vinsonii | Incidental | Mouse, dog, domestic cat | Endocarditis, bacteremia | |

| B. washoensis | Incidental | Squirrel | Myocarditis | |

| B. rochalimae | Incidental | Unknown | Carrion's disease-like symptoms | |

| References:[14][15][16][17][13] | ||||

Treatment

Treatment is dependent on which species or strain of Bartonella is found in a given patient. While Bartonella species are susceptible to a number of standard antibiotics in vitro—macrolides and tetracycline, for example—the efficacy of antibiotic treatment in immunocompetent individuals is uncertain.[13] Immunocompromised patients should be treated with antibiotics because they are particularly susceptible to systemic disease and bacteremia. Drugs of particular effectiveness include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and rifampin; B. henselae is generally resistant to penicillin, amoxicillin, and nafcillin.[13]

Epidemiology

Homeless intravenous drug users are at high risk for Bartonella infections, particularly B. elizabethae. B. elizabethae seropositivity rates in this population range from 12.5% in Los Angeles ,[18] to 33% in Baltimore, Maryland,[19] 46% in New York City ,[20] and 39% in Sweden.[21]

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN).[1] The phylogeny is based on whole-genome analysis.[22]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature". https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/bartonella.

- ↑ Brenner, D. J.; O'Connor, S. P.; Winkler, H. H.; Steigerwalt, A. G. (1993). "Proposals To Unify the Genera Bartonella and Rochalimaea, with Descriptions of Bartonella quintana comb. nov., Bartonella vinsonii comb. nov., Bartonella henselae comb. nov., and Bartonella elizabethae comb. nov., and To Remove the Family Bartonellaceae from the Order Rickettsiales". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 43 (4): 777–786. doi:10.1099/00207713-43-4-777. ISSN 0020-7713. PMID 8240958.

- ↑ Peters, D.; R. Wigand (1955). "Bartonellaceae". Bacteriol. Rev. 19 (3): 150–159. doi:10.1128/MMBR.19.3.150-159.1955. PMID 13260099.

- ↑ Walker DH (1996). "Rickettsiae". in Baron S. Rickettsiae. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.section.2138.

- ↑ "Zoonoses dues aux bactéries du genre Bartonella: nouveaux réservoirs? nouveaux vecteurs?" (in fr). Bull. Acad. Natl. Med. 189 (3): 465–77; discussion 477–80. 2005. PMID 16149211. http://www.academie-medecine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/2005.3.pdf.

- ↑ "Bartonella quintana in a 4000-year-old human tooth". J. Infect. Dis. 191 (4): 607–11. 2005. doi:10.1086/427041. PMID 15655785.

- ↑ "etymologia: Bartonella henselae". Emerging Infectious Diseases 14 (6): 980. June 2008. doi:10.3201/eid1406.080980. ISSN 1080-6040.

- ↑ "Potential for tick-borne bartonellosis". Emerg Infect Dis 16 (3): 385–91. March 2010. doi:10.3201/eid1603.091685. PMID 20202411.

- ↑ Telford SR III; Wormser GP (March 2010). "Bartonella spp. transmission by ticks not established". Emerg Infect Dis 16 (3): 379–84. doi:10.3201/eid1603.090443. PMID 20202410.

- ↑ "Vector transmission of Bartonella species with emphasis on the potential for tick transmission". Med Vet Entomol 22 (1): 1–15. Mar 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00713.x. PMID 18380649.

- ↑ "Cat scratch disease and arthropod vectors: more to it than a scratch?". J Am Board Fam Med 23 (5): 685–6. Sep–Oct 2010. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.05.100025. PMID 20823366.

- ↑ "Bartonella spp. in pets and effect on human health". Emerg Infect Dis 12 (3): 389–94. Mar 2006. doi:10.3201/eid1203.050931. PMID 16704774.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Recommendations for treatment of human infections caused by Bartonella species". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 (6): 1921–33. 2004. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.6.1921-1933.2004. PMID 15155180.

- ↑ "Genetic classification and differentiation of Bartonella species based on comparison of partial ftsZ gene sequences". J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 (10): 3641–7. 2002. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.10.3641-3647.2002. PMID 12354859.

- ↑ "Natural history of Bartonella infections (an exception to Koch's postulate)". Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9 (1): 8–18. 2002. doi:10.1128/CDLI.9.1.8-18.2002. PMID 11777823. PMC 119901. http://cdli.asm.org/cgi/content/full/9/1/8.

- ↑ "Carrion's disease (Bartonellosis bacilliformis) confirmed by histopathology in the High Forest of Peru". Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 46 (3): 171–4. 2004. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652004000300010. PMID 15286824.

- ↑ Pulliainen, Arto T.; Lilley, Thomas M.; Vesterinen, Eero J.; Veikkolainen, Ville (2014). "Bats as Reservoir Hosts of Human Bacterial Pathogen, Bartonella mayotimonensis - Volume 20, Number 6—June 2014 - Emerging Infectious Disease journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases 20 (6): 960–7. doi:10.3201/eid2006.130956. PMID 24856523.

- ↑ Smith HM; Reporter R; Rood MP et al. (2002). "Prevalence study of antibody to ratborne pathogens and other agents among patients using a free clinic in downtown Los Angeles". J. Infect. Dis. 186 (11): 1673–6. doi:10.1086/345377. PMID 12447746.

- ↑ "Antibodies to Bartonella species in inner-city intravenous drug users in Baltimore, Md". Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (21): 2491–5. 1996. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.21.2491. PMID 8944742.

- ↑ "Evidence of rodent-associated Bartonella and Rickettsia infections among intravenous drug users from Central and East Harlem, New York City". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65 (6): 855–60. 2001. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.855. PMID 11791987.

- ↑ "Bartonella spp. antibodies in forensic samples from Swedish heroin addicts". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 990 (1): 409–13. 2003. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07402.x. PMID 12860665. Bibcode: 2003NYASA.990..409M.

- ↑ "Analysis of 1,000+ Type-Strain Genomes Substantially Improves Taxonomic Classification of Alphaproteobacteria". Front. Microbiol. 11: 468. 2020. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00468. PMID 32373076.

External links

- Bartonella genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- New Bartonella Species That Infects Humans Discovered

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|