Biology:Elephantidae

Elephantidae is a family of large, herbivorous proboscidean mammals which includes the living elephants (belonging to the genera Elephas and Loxodonta), as well as a number of extinct genera like Mammuthus (mammoths) and Palaeoloxodon. They are large terrestrial mammals with a snout modified into a trunk and teeth modified into tusks. Most genera and species in the family are extinct. Some extinct members are among the largest known terrestrial mammals ever.

The family was first described by John Edward Gray in 1821,[1] and later assigned to taxonomic ranks within the order Proboscidea. Elephantidae has been revised by various authors to include or exclude other extinct proboscidean genera.

Description

Elephantids are distinguished from more basal proboscideans like gomphotheres by their teeth, which have parallel lophs, formed from the merger of the cusps found in the teeth of more basal proboscideans, which are bound by cementum.[2] In later elephantids, these lophs became narrow lamellae/plates,[3] which are pockets of enamel filled with dentine, which are arranged successively like a concertina.[4] The number of lophs/lamellae per tooth, as well as the tooth crown height (hypsodonty) is greater in later species.[5] Elephantids chew using a proal jaw movement involving a forward stroke of the lower jaws, different from the oblique movement using side to side motion of the jaws in more primitive proboscideans.[6] The most primitive elephantid Stegotetrabelodon had a long lower jaw with lower tusks and retained permanent premolars similar to many gomphotheres, while modern elephantids lack permanent premolars, with the lower jaw being shortened (brevirostrine) and lower tusks being absent.[5]

-

Molar of Tetralophodon, a "tetralophodont gomphothere"

-

Worn molar of Stegotetrabelodon, a primitive elephantid

-

Molar of a modern African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana)

-

Tooth of Mammuthus sp.

-

Cross section through elephantid molars

Elephantids are typically sexually dimorphic, with substantially larger males, with an accelerated growth rate over a longer period of time than females. Elephantidae contains some of the largest known proboscideans, with fully-grown males of some species of mammoths and Palaeoloxodon having average body masses of 11 tonnes (24,000 lb) and 13 tonnes (29,000 lb) respectively, making them among the largest terrestrial mammals ever. One species of Palaeoloxodon, Palaeoloxodon namadicus, has been suggested to have been possibly the largest land mammal of all time, though this remains speculative due to the fragmentary nature of known remains.[7] In comparison to more basal elephantimorphs like gomphotheres, the bodies of elephantids tend to be proportionally shorter from front to back, as well having more elongate limbs with more slender limb bones.[8]

-

Skeleton of an African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) bull

-

Skeleton of a steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii) in front-on (without head) side-on and top-down views

-

Skeleton of an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus)

-

Skeleton of a straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) bull

-

Size comparison of Palaeoloxodon falconeri a dwarf elephant species from Sicily, and one of the smallest elephantids known

Ecology

Living female and juvenile elephants live in matriarchal (female-led) herds of related individuals, with males leaving these groups to live solitarily or in loose male bonding groups upon reaching adolescence around 14–15 years of age.[9][10] Evidence has been found that extinct elephantids, including the most primitive elephantid, Stegotetrabelodon, also lived in herds based on footprint tracks.[9][11] From around the age of 20, adult male elephants peridiodically enter a state of heightened aggression known as musth, where stronger males assert dominance over weaker males, on rare occasions breaking out into fights between rival males.[10] Analysis of testosterone levels in woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) tusks indicates that they also went into musth,[12] and healed wounds to some straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) skeletons may have been the result of fighting between rival males.[13] The earliest elephantid, Stegotetrabelodon, was a mixed feeder to a grazer based on dental mesowear analysis.[14] Modern elephants are browsers[15] to mixed feeders.[16] Some extinct elephantids, like Palaeoloxodon recki and the woolly mammoth, were dedicated grazers.[17][18]

Classification

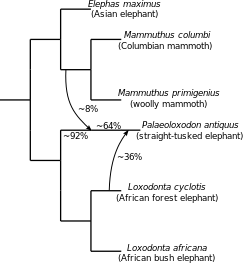

Some authors have suggested to classify the family into two subfamilies, Stegotetrabelodontinae, which is monotypic, only containing Stegotetrabelodon, and Elephantinae, containing all other elephantids.[5] Recent genetic research has indicated that Elephas and Mammuthus are more closely related to each other than to Loxodonta, with Palaeoloxodon closely related to Loxodonta. Palaeoloxodon also appears to have received extensive hybridisation with the African forest elephant, and to a lesser extent with mammoths.[19]

Living species

- Loxodonta (African)

- L. africana African bush elephant

- L. cyclotis African forest elephant

- Elephas (Asiatic)

- E. maximus Asian elephant

- E. m. maximus Sri Lankan elephant

- E. m. indicus Indian elephant

- E. m. sumatranus Sumatran elephant

- E. m. borneensis Borneo elephant

- E. maximus Asian elephant

Classification

- Elephantidae

- Subfamily Stegotetrabelodontinae

- †Stegotetrabelodon (4 species)

- Subfamily Elephantinae

- †Primelephas (2 species)

- Elephas (7+ species)

- †Stegoloxodon (2 species)

- Loxodonta (6 species)

- †Palaeoloxodon (14+ species)

- †Phanagoroloxodon (1 species)

- †Mammuthus (10 species)

- †Stegodibelodon (1 species)

- †Selenetherium (1 species)

- Subfamily Stegotetrabelodontinae

Evolutionary history

During the Late Miocene, around 10-8 million years ago, the earliest members of the family Elephantidae emerged in Afro-Arabia, having originated from gomphotheres, most likely from members of the genus Tetralophodon.[20][21] The earliest members of the modern genera of Elephantidae appeared during the latest Miocene–early Pliocene around 6-5 million years ago. The elephantid genera Elephas (which includes the living Asian elephant) and Mammuthus (mammoths) migrated out of Africa during the late Pliocene, around 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago.[22] Mammoths then migrated into North America around 1.5 million years ago.[23] At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago the elephantid genus Palaeoloxodon dispersed outside of Africa, becoming widely distributed in Eurasia.[24] Palaeoloxodon became extinct as part of the Late Pleistocene extinctions, with mammoths only surviving in relict populations on islands around the Bering Strait into the Holocene, with their latest survival being on Wrangel Island, where they persisted until around 4,000 years ago.[25][26]

See also

References

- ↑ Gray, John Edward (1821). "On the natural arrangement of vertebrose animals". London Medical Repository 15: 297–310. https://archive.org/details/londonmedicalre08unkngoog.

- ↑ Lister, Adrian M. (2013-06-26). "The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans". Nature 500 (7462): 331–334. doi:10.1038/nature12275. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23803767. Bibcode: 2013Natur.500..331L.

- ↑ Saarinen, Juha; Lister, Adrian M. (2023-08-14). "Fluctuating climate and dietary innovation drove ratcheted evolution of proboscidean dental traits" (in en). Nature Ecology & Evolution 7 (9): 1490–1502. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02151-4. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 37580434. Bibcode: 2023NatEE...7.1490S.

- ↑ V.L. Herridge Dwarf Elephants on Mediterranean Islands: A Natural Experiment in Parallel Evolution. PhD Thesis, Vol 1. p. 32 University College London (2010)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Athanassiou, Athanassios (2022), Vlachos, Evangelos, ed., "The Fossil Record of Continental Elephants and Mammoths (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Elephantidae) in Greece" (in en), Fossil Vertebrates of Greece Vol. 1 (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 345–391, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68398-6_13, ISBN 978-3-030-68397-9, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-68398-6_13, retrieved 2023-11-21

- ↑ Saegusa, Haruo (March 2020). "Stegodontidae and Anancus: Keys to understanding dental evolution in Elephantidae" (in en). Quaternary Science Reviews 231. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106176. Bibcode: 2020QSRv..23106176S. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277379119302665.

- ↑ Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app61/app001362014.pdf.

- ↑ Bader, Camille; Delapré, Arnaud; Göhlich, Ursula B.; Houssaye, Alexandra (November 2024). "Diversity of limb long bone morphology among proboscideans: how to be the biggest one in the family" (in en). Papers in Palaeontology 10 (6). doi:10.1002/spp2.1597. ISSN 2056-2799. Bibcode: 2024PPal...10E1597B.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Neto de Carvalho, Carlos; Belaústegui, Zain; Toscano, Antonio; Muñiz, Fernando; Belo, João; Galán, Jose María; Gómez, Paula; Cáceres, Luis M. et al. (2021-09-16). "First tracks of newborn straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus)" (in en). Scientific Reports 11 (1): 17311. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-96754-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 34531420. Bibcode: 2021NatSR..1117311N.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 LaDue, Chase A.; Schulte, Bruce A.; Kiso, Wendy K.; Freeman, Elizabeth W. (2021-09-17). "Musth and sexual selection in elephants: a review of signalling properties and potential fitness consequences". Behaviour 159 (3–4): 207–242. doi:10.1163/1568539x-bja10120. ISSN 0005-7959. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539x-bja10120.

- ↑ Bibi, Faysal; Kraatz, Brian; J. Beech, Mark; Hill, Andrew (2022), Bibi, Faysal; Kraatz, Brian; Beech, Mark J. et al., eds., "Fossil Trackways of the Baynunah Formation" (in en), Sands of Time (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 283–298, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-83883-6_17, ISBN 978-3-030-83882-9, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-83883-6_17, retrieved 2024-01-18

- ↑ Cherney, Michael D.; Fisher, Daniel C.; Auchus, Richard J.; Rountrey, Adam N.; Selcer, Perrin; Shirley, Ethan A.; Beld, Scott G.; Buigues, Bernard et al. (2023-05-18). "Testosterone histories from tusks reveal woolly mammoth musth episodes" (in en). Nature 617 (7961): 533–539. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06020-9. ISSN 0028-0836. Bibcode: 2023Natur.617..533C. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06020-9.

- ↑ MR Palombo, E Albayrak, F Marano (2010) The straight-tusked Elephants from Neumark Nord, a glance to a lost world. In: Meller H (ed) Elefantenreich—eine Fossilwelt in Europa. Archäologie in Sachsen-Anhalt, Sonderband, Halle-Saale, pp 219–247 (p. 237 for relevant content)

- ↑ Saarinen, Juha; Lister, Adrian M. (2023-08-14). "Fluctuating climate and dietary innovation drove ratcheted evolution of proboscidean dental traits" (in en). Nature Ecology & Evolution 7 (9): 1490–1502. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02151-4. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 37580434. Bibcode: 2023NatEE...7.1490S.

- ↑ Cerling, Thure E.; Harris, John M.; Leakey, Meave G. (1999-08-20). "Browsing and grazing in elephants: the isotope record of modern and fossil proboscideans". Oecologia 120 (3): 364–374. doi:10.1007/s004420050869. ISSN 0029-8549. Bibcode: 1999Oecol.120..364C. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s004420050869.

- ↑ Koirala, Raj Kumar; Raubenheimer, David; Aryal, Achyut; Pathak, Mitra Lal; Ji, Weihong (December 2016). "Feeding preferences of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in Nepal" (in en). BMC Ecology 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s12898-016-0105-9. ISSN 1472-6785. PMID 27855704. Bibcode: 2016BMCE...16...54K.

- ↑ Manthi, Fredrick Kyalo; Sanders, William J.; Plavcan, J. Michael; Cerling, Thure E.; Brown, Francis H. (September 2020). "Late Middle Pleistocene Elephants from Natodomeri, Kenya and the Disappearance of Elephas (Proboscidea, Mammalia) in Africa" (in en). Journal of Mammalian Evolution 27 (3): 483–495. doi:10.1007/s10914-019-09474-9. ISSN 1064-7554. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10914-019-09474-9.

- ↑ Rivals, Florent; Semprebon, Gina M.; Lister, Adrian M. (September 2019). "Feeding traits and dietary variation in Pleistocene proboscideans: A tooth microwear review". Quaternary Science Reviews 219: 145–153. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.06.027. Bibcode: 2019QSRv..219..145R. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277379119302641.

- ↑ Palkopoulou, Eleftheria; Lipson, Mark; Mallick, Swapan; Nielsen, Svend; Rohland, Nadin; Baleka, Sina; Karpinski, Emil; Ivancevic, Atma M. et al. (2018-03-13). "A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (11): E2566–E2574. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720554115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 29483247. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115E2566P.

- ↑ Saegusa, H.; Nakaya, H.; Kunimatsu, Y.; Nakatsukasa, M.; Tsujikawa, H.; Sawada, Y.; Saneyoshi, M.; Sakai, T. (2014). "Earliest elephantid remains from the late Miocene locality, Nakali, Kenya". VIth International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives. 102. Thessaloniki: School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. p. 175. ISBN 978-960-9502-14-6. https://apo.ansto.gov.au/dspace/bitstream/10238/9340/2/icmr_volume_low.pdf#page=188.

- ↑ Sanders, William J. (2022), Bibi, Faysal; Kraatz, Brian; Beech, Mark J. et al., eds., "Proboscidea from the Baynunah Formation" (in en), Sands of Time, Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 141–177, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-83883-6_10, ISBN 978-3-030-83882-9, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-83883-6_10, retrieved 2025-04-17

- ↑ Iannucci, Alessio; Sardella, Raffaele (2023-02-28). "What Does the "Elephant-Equus" Event Mean Today? Reflections on Mammal Dispersal Events around the Pliocene-Pleistocene Boundary and the Flexible Ambiguity of Biochronology". Quaternary 6 (1): 16. doi:10.3390/quat6010016. Bibcode: 2023Quat....6...16I.

- ↑ Lister, A. M.; Sher, A. V. (2015). "Evolution and dispersal of mammoths across the Northern Hemisphere". Science 350 (6262): 805–809. doi:10.1126/science.aac5660. PMID 26564853. Bibcode: 2015Sci...350..805L.

- ↑ Lister, A. M. (2004). "Ecological Interactions of Elephantids in Pleistocene Eurasia". Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor. Oxbow Books. pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-1-78570-965-4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264788794.

- ↑ Cantalapiedra, J. L.; Sanisidro, Ó.; Zhang, H.; Alberdi, M. T.; Prado, J. L.; Blanco, F.; Saarinen, J. (2021). "The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity". Nature Ecology & Evolution 5 (9): 1266–1272. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w. PMID 34211141. Bibcode: 2021NatEE...5.1266C. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01498-w.

- ↑ Rogers, R. L.; Slatkin, M. (2017). "Excess of genomic defects in a woolly mammoth on Wrangel island". PLOS Genetics 13 (3). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006601. ISSN 1553-7404. PMID 28253255.

External links

Data related to Elephantidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Elephantidae at Wikispecies

Wikidata ☰ Q2372824 entry

|