Biology:European anchovy

| European anchovy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Animalia |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Chordata |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Actinopterygii |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Clupeiformes |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Engraulidae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Engraulis |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">E. encrasicolus |

| Binomial name | |

| Engraulis encrasicolus | |

The European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) is a forage fish somewhat related to the herring. It is a type of anchovy; anchovies are placed in the family Engraulidae. It lives off the coasts of Europe and Africa, including in the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, and the Sea of Azov. It is fished by humans throughout much of its range.[1]

Etymology

This species can be fished from the shore with simpler gear, such as beach seines,[1] and it has been widely-eaten for millennia.[2] The species has been fished since ancient times.[1] Both the species name, "Engraulis" (ἐγγραυλίς), and the specific name "encrasicolus" (ἐγκρασίχολος) are names from Ancient Greek, meaning "anchovy" and "small fish" respectively.[3]

Description

It is easily distinguished by its deeply cleft mouth, the angle of the gape being behind the eyes. The pointed snout extends beyond the lower jaw. The fish resembles a sprat in having a forked tail and a single dorsal fin, but the body is round and slender.[citation needed] The record weight for a single fish is 49 g (1.7 oz).[4] The maximum recorded length is 21 cm (8 1⁄8 in).[citation needed] 13.5 cm (5.3 in) is a more typical length.[5] It has a silver underbelly and blue, green or grey back and sides.[4] A silver stripe along the side fades away with age.[5]

Habitat and ecology

The European anchovy is a coastal pelagic species; in summer, it usually lives in water less than 50 m deep (although, in the Mediterranean, it goes to depths of 200 m in winter), and it may go as deep as 400 m. As it is euryhaline, it can live in water with a salinity of 5–41[1] PSU (sea water salinity is usually 35 PSU[6]). It can therefore live in brackish water in lagoons, estuaries, and lakes.[1]

European anchovies eat plankton, mostly copepods and the eggs and larvae of fish, molluscs, and cirripedes.[7] They are migratory, often travelling northwards in summer and south in winter. They form large schools,[1] and may form bait balls when threatened (see image, below).

European anchovies are eaten by many species of fish, birds and marine mammals.[4]

Life cycle

The species spawn multiply[5] in warm periods from about April to November, depending on when the temperatures are warm enough. At least some local subpopulations have separate spawning grounds, and are thus genetically distinct,[1] although spawning grounds shift.[5] Some spawn in fresh water. The shape of the eggs is ellipsoidal to oval.[5] The eggs float as plankton in the upper 50 m of the water column for about 24–65 hours before hatching. The hatched larvae are transparent and grow rapidly; a year later, in the unlikely event that they survive, they will be 9–10 cm (3.5–3.9 in) long.[1] The females are larger than the males.[8] When they reach a length of 12–13 cm (4.7–5.1 in), they spawn for the first time. A survey in southwestern Africa found no specimens older than three years.[1]

Distribution

Europe

European anchovies are abundant in the Mediterranean and formerly also the Black and Azov seas (see below). They are regularly caught on the coasts of Bulgaria, Croatia, France , Georgia, Greece, Italy, Albania, Romania, Russia , Spain , Turkey and Ukraine . The range of the species also extends along the Atlantic coast of Europe to the south of Norway . In winter it is common off Devon and Cornwall (United Kingdom ), but has not hitherto been caught in such numbers as to be of commercial importance.

Zuiderzee and English Channel

Formerly they were caught in large numbers off the coast of the Netherlands in summer when they entered the Wadden Sea and Zuiderzee. After the closing of the Zuiderzee they were still found in the Wadden Sea until the 1960s. They were also caught in the estuary of the Scheldt.

There is reason to believe that anchovies at the western end of the English Channel in November and December migrate from the Zuiderzee and the Scheldt in the autumn, returning there the following spring. They were believed to be an isolated population, for none come from the south in summer to occupy the English Channel, though the species does exist off the coast of Portugal. The explanation appears to be that in summer, the shallow and landlocked waters of the Zuiderzee and the sea off the Dutch coast get warmer than the coastal waters off Britain, so anchovies can spawn and maintain their numbers in warmer Dutch waters better.

Dutch naturalists on the shores of the Zuiderzee first described their reproduction and development. Spawning takes place in June and July. The eggs are buoyant and transparent like most fish eggs, but are unusual in being sausage-shaped, instead of globular. They resemble sprat and pilchard eggs in having a segmented yolk and no oil globule. Larvæ hatch two or three days after fertilization, and are minute and transparent. In August young specimens, c. 38 to 89 mm (1 1⁄2 to 3 1⁄2 in) in length, are found in the Zuiderzee, and these must derive from the previous summer's spawning.

There is no evidence to decide the question whether all the young anchovies as well as the adults leave the Zuiderzee in autumn, but, considering the winter temperature there, it is probable that they do. Eggs have also been found in the Bay of Naples, near Marseilles, off the coast of the Netherlands, and once at least off the coast of Lancashire. The occurrence of anchovies in the English Channel has been carefully studied at the Marine Biological Association Laboratory in Plymouth. They were most abundant in 1889 and 1890. In the former year considerable numbers were taken off Dover in drift nets of small mesh used for the capture of sprats. In the following December large numbers were taken together with sprats at Torquay. In November 1890 a thousand of the fish were obtained in two days from the pilchard boats fishing near Plymouth; these were caught near the Eddystone.

Mediterranean, Black Sea and Azov Sea

In areas around the Black Sea, the European anchovy is called gávros (Γαύρος) in Greek, hamsie in Romanian, ქაფშია (Kapshia) or ქაფშა (Kapsha) in Georgian, hamsi in Turkish, hapsi in Pontic dialect of Turkish, hapsia (plural) in Pontic Greek, Hapchia in Laz,[9] хамсия (hamsiya) in Bulgarian, and хамса (hamsa) in Russian and Ukrainian. Its Ancient Greek name was ἀφύη, aphýē, later Latinized into apiuva, hence the standard Italian acciuga and the Croatian inćun through the Genoese dialectal anciúa. Modern Greek also uses αντζούγια antsúya, a variant of the Genoese form, for processed – as opposed to the fresh gávros – anchovy products.

Black Sea adult anchovies can reach around 12–15 cm (4 1⁄2–6 in). In the summer, hamsi migrates north to warm shallow waters of the Azov Sea to feed and breed, returning to the deep for the winter by migrating through the Strait of Kerch. During migration the fish moves in huge schools, and are actively hunted by gulls and dolphins. Hamsi makes up a considerable part of fishing and fish processing industries, either canned or frozen. In Turkey, it is the staple food of the local Black Sea cuisine,[10] widely used in pan dishes, baked goods, even as dessert. In Bulgaria hamsiya is traditionally fried and served in cheap fast-food restaurants along the shore, typically with beer. Since the 1990s the dominant position of fried hamsiya is fading but still popular.

Anchovy populations in the Mediterranean were severely depleted in the 1980s by the invasive comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi which eats the eggs and young, they have since stabilized albeit at a much lower level.

Off Africa (East Atlantic and West Indian Oceans)

European anchovies are commercially important down the west coast of Africa, although they are most abundant at the north end of this range. The species is most commercially important in Morocco. In Mauritania, artisanal fishers do not target the species, and commercial fisheries have size limitations.

In West Africa, these anchovies are widely fished and eaten. In Nigeria, Ghana, and Benin, it is an abundant and important commercial species. After the end of the upwelling season ends the Sardinella fishery, fishers change net size to catch anchovies. In Guinea, the Gambia, and Senegal, it is not an important commercial species.

South of the Angola/Namibia border, Engraulis encrasicolus (the European anchovy) mixes with Engraulis capensis, the South African anchovy. The Namibian fishery is significantly involved in fishmeal and fish oil production.

European anchovies are also found in upwelling areas off the east coast of Africa.[1]

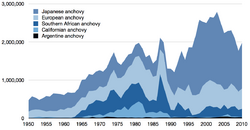

Fisheries

The IUCN considers the fisheries to be abundant and fully exploited, and in need of careful monitoring.[1] The highly international species has no concerted management plan.[5]

Local populations fluctuate, and have shown large fluctuations in the past.[1] These fluctuations are not well understood.[5] Some past declines have been due to environmental problems, local overfishing, and invasive species from ballast water. Mnemiopsis leidyi is an invasive species which eats European anchovy eggs.[1] Some past fluctuations are likely due to climate change.[4]

European anchovies are caught with purse seines, lamparas, trawls and beach seines.[1] Bycatch is thought, on the basis of insufficient data, to be minor.[5]

Human uses

European anchovies are widely eaten.[1] Anchovies are considered an oily fish; they have a salty, strong taste. Some people eat them raw.[4] European anchovies are sold fresh, dried, smoked, salted, in oil, frozen, canned, and processed into fishmeal and fish oil.[4][1] Their ease of preservation has made them a traditional item for long-distance trade.[4] Anchovies are also used as fishing bait.[1][8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Tous, P.; Sidibé, A.; Mbye, E.; de Morais, L.; Camara, Y.H.; Adeofe, T.A.; Monroe, T.; Camara, K. et al. (2015). "Engraulis encrasicolus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T198568A15546291. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T198568A15546291.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/198568/15546291. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Thring, Oliver (18 January 2011). "Consider the anchovy" (in en). https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/wordofmouth/2011/jan/18/consider-the-anchovy.

- ↑ "Family ENGRAULIDAE Gill 1861 (Anchovies)". https://etyfish.org/engraulidae/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "European Anchovy". 12 March 2014. http://britishseafishing.co.uk/european-anchovy/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "FishSource – European anchovy – Black Sea". https://www.fishsource.org/stock_page/1739.

- ↑ Culkin, F.; Smith, N. D. (1980). "Determination of the Concentration of Potassium Chloride Solution Having the Same Electrical Conductivity, at 15 C and Infinite Frequency, as Standard Seawater of Salinity 35.0000 ‰ (Chlorinity 19.37394 ‰)". IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. OE-5 (1): 22–23. doi:10.1109/JOE.1980.1145443. Bibcode: 1980IJOE....5...22C.

- ↑ Mustać, Bosiljka; Hure, Marijana (15 July 2020). "The diet of the anchovy Engraulis encrasicolus (Linnaeus, 1758) during the spawning season in the eastern Adriatic Sea". Acta Adriatica 61 (1): 57–66. doi:10.32582/aa.61.1.4.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 http://aquaticcommons.org/9289/1/na_2684.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ Özhan Öztürk. Karadeniz Ansiklopedik Sözlük. 2005. pp. 486–488

- ↑ Black Sea Region cuisine of Turkey

References

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Engraulis encrasicolus" in FishBase. October 2005 version.

- Kube, Sandra; Postel, Lutz; Honnef, Christopher & Augustin, Christina B. (2007): Mnemiopsis leidyi in the Baltic Sea – distribution and overwintering between autumn 2006 and spring 2007. Aquatic Invasions 2(2): 137–145.

Wikidata ☰ Q188387 entry

|