Biology:Electrocommunication

Electrocommunication is the communication method used by weakly-electric fish. Weakly-electric fish are a group of animals that utilize a communicating channel that is "invisible" to most other animals: electric signaling. Electric fish communicate by generating an electric field that a second individual receives with its electroreceptors. The fish interprets the message using the signal's frequencies, waveforms, delay, etc.[1] The best studied species are two freshwater lineages- the African Mormyridae and the South American Gymnotiformes.[2] While weakly-electric fish are the only group that have been identified to carry out both generation and reception of electric fields, other species either generate signals or receive them, but not both. Animals that either generate or receive electric fields are found only in wet or aquatic environments due to water's relatively low electrical resistance, compared to other substances (e.g. air).[3] So far, communication between electric fish has been identified mainly to serve the purpose of conveying information such as:

- species

- courtship and biological sex

- motivational status (e.g. attack warning, submission, etc.)

- environmental conditions

Overview of weakly-electric fish

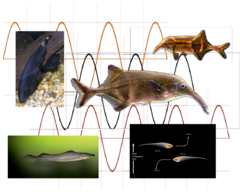

File:Vadamans rasp movie 1.theora.ogv Electric fish are capable of generating external electric fields or receiving electric fields (electroreception). Electric fish can be further divided into three categories: strongly discharging, weakly discharging, and fish that sense but are unable to generate electric fields.[1] Strongly electric fish generate strong electric field up to 500 volts for predatory purposes;[4] Strongly electric fish include both marine and fresh water fish: (two freshwater taxa - African electric catfish (Malapterurus electricus) and the Neotropical electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and the marine torpedo rays (Torpedo)). Weakly-electric fish generate electric fields mainly for communication and electrolocation purposes. Weakly-electric fish are found in fresh water only and include African freshwater Mormyridae and Gymnarchus and Neotropical electric knifefish. Lastly, fish that are only able to detect electrical signals include sharks, rays, skates, catfish, and a number of other groups (see Electroreception).[4]

Electric fish generate discharge from electric organs located near the tail region. Electric organs are mostly derived from muscle cells (myogenic); except in one gymnotiform family, which has electric organs derived from neurons (neurogenic organs). To detect the electric signals, electric fish have two types of receptive cells - ampullary and tuberous electroreceptors.

Electroreceptor organs

All organisms respond to sufficiently strong electric shocks, but only some aquatic vertebrates can detect and utilize weak electric fields such as those that occur naturally. These aquatic organisms are therefore called electroreceptive. (For an example, human-beings react to strong electric currents with a sense of pain and sometimes a mixture of other senses; however, we cannot detect weakly-electric fields and therefore are not electroreceptive.) The ability to sense and utilize electric fields was found almost solely in lower, aquatic vertebrates (fish and some amphibians). Terrestrial animals, with very few exceptions, lack this electric sensing channel due to low conductivity of air, soil, or media other than aqueous environment. Exceptions include the Australian monotremes, i.e. the echidna which eats mainly ants and termites, and the semi-aquatic platypus that hunts by utilizing electric fields generated by invertebrate prey.[5]

In order to detect weakly-electric fields, animals must possess electroreceptors (receptive organs) that detect electric potential differences. For electric fish, receptive organs are groups of sensory cells rooted in epidermal pits, which look like small spots on the skin. In each receptive organ, there are sensory cells embedded in the bottom of the opened "pit" that faces outside. Electroreceptors detect electric signals by building up a potential difference between the outside environment and the fish body's internal environment. Current flow due to such potential difference further results in a receptor potential that is presynaptic to the sensory fibers. Finally, this receptor potential leads to action potential fired by sensory cells.[6]

Electric fish carry a variety of sensitive receptive organs that are tuned to different types and ranges of signals. To classify types of electroreceptors, the first differentiation point should be made between ampullary and tuberous organs, which exist in both mormyrids and gymnotiforms. These two types of electric receptors have very distinct anatomical differences- ampullary organs have their opened "pit" formed in a duct-like structure and filled with mucous substance; the "pit" of a tuberous organ, on the other hand, is loosely packed with epithelial cells. In addition to anatomical differences, these two receptors also have distinctive functional differences. Ampullary organs are more sensitive and tuned to a low frequency range of 1–10 Hz, which is the range of non-electrogenic, biological source of electricity. Therefore, ampullary organs are mainly used for passive electrolocation. On the other hand, tuberous, which are used for electrocommunication by weakly-electric fish, are less sensitive and tuned to much higher frequencies.[6][7]

Classification of the two types of receptive organs

| Type | Structure | Function | Sensitivity | Where found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampullary | Open pit/ Filled with mucous | Electrolocation/ Locate preys | 0.01 μV/cm in marine species, 0.01 mV/cm in freshwater; Sensitive to DC fields/ Low frequencies less than 50 Hz | Sharks & Rays; Non-teleost fish; Certain teleosts (mormyrids, certain notopterus, gymnotiforms, catfish); Amphibians (except frogs and toads) |

| Tuberous | Covered by skin - loosely packed with epithelia cells | Electrocommunication | 0.1 mV to 10 mV/cm/ Tens of Hz to more than 1 kHz. | Mormyrid fish; Gymnotiform fish |

Tuberous organs

Tuberous organs, the type of receptive organ used for electrocommunication, can be divided into two types, depending on the way information is encoded: time coders and amplitude coders. There are multiple forms of tuberous organs in each time and amplitude coders, and all weakly-electric fish species possess at least one form of the two coders. Time coder fires phase-locked action potential (meaning, the waveform of the action potential is always the same) at a fixed delay time after each outside transient is formed. Therefore, time coders neglect information about waveform and amplitude but focus on frequency of the signal and fire action potentials on a 1:1 basis to the outside transient. Amplitude coders, on the contrary, fire according to the EOD amplitude. While both wave-type and pulse-type fish have amplitude coders, they fire in different ways: Receptors of wave-type fish continuously fire at a rate according to their own EOD amplitude; on the other hand, receptors of pulse-type fish fire burst of spikes to each EOD detected, and the number of spikes in each burst is correlated to the amplitude of the EOD. Tuberous electroreceptors show a V-shaped threshold tuning curve (similar to auditory system), which means that they are tuned to a particular frequency. This particular tuned-in frequency is usually closely matched to their own EOD frequency.[9]

Classification of tuberous organs

| Type | Fire according to | Method of encoding | Found in |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Coder | Frequency of received EOD | Fires action potential in a 1:1 ratio to the received EOD | Both types of weakly-electric fish |

| Amplitude Coder | Amplitude of received EOD | Wave-type: continuously fire at a rate according to EOD amplitude/ Pulse-type: number of bursts in each spike is depend on the amplitude of EOD | Both types of weakly-electric fish |

Electric organs

Weakly-electric fish generate Electric Organ Discharge (EOD) with specialized compartments called electric organ. Almost all the weakly-electric fish have electric organs derived from muscle cells (myogenic) ; the only exception is the Apteronotidae, a family under Gymnotiforms that has electric organs derived from nerve cells (neurogenic). Myogenic electrocytes are arranged into columns of small, disks-like cells called electroplate. The exceptional family, Apteronotidae, also carries myogenic electric organs in larval stages. However, as the fish matures, electrogenic organs derived from central spinal cord gradually replace the muscle cell-derived electric cells.[10]

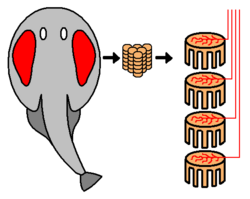

Discharge of an electric organ begins with central command from a medullary pacemaker that determines the frequency and rhythm of EODs. These two characteristics (frequency and rhythm) of EODs are also referred to as SPI- sequence of pulse intervals. The command from medullary pacemaker is then passed on by spinal electromotor neurons to electrocytes forming the electric organ, which determine the waveform of the EODs based on its morphophysiological properties. As command from pacemaker reaches electric organ, it opens up all the sodium channels, causing net sodium ion flux in one direction. The direction will either be towards or away from the head, and brings simultaneous depolarization of all electrocytes on the same side of cell. The result is a positive polarity at the fish's head relative to the tail, or vice versa: a dipole system. The polarity built up by the electric organ therefore sets up an electrostatic field in the water.[4][11]

Electric organs are quite different between mormyrids and gymnotiforms and therefore will be presented separately:

Mormyrids

In mormyrids, the electric organ is fairly small and located only in the caudal peduncle region (the narrow part of a fish's body where the caudal fin is attached). Electric organs are composed of disk-like electrocytes serially connected together in two columns, and each column resides on one side of the spinal cord. The myogenic electrocytes are identical to each other and are discharged in synchrony. The electrical potential recorded from a single electrocyte is equivalent to the miniature version a complete EOD measured outside of the fish. Electrocytes also have an important structure called "stalk," which are tentacle or tube-like structures that extend out from each electrocyte. Different stalk-electrocyte systems have been observed, which include stalks that penetrate the electrocytes, innervate electrocytes from the posterior or anterior side. Multiple stalks from one electrocyte eventually fuse together to form a large stalk that receives innervation from spinal-electromotor neurons. Different morphological structures of the stalk/ electrocyte systems result in differences in electric current flow, which further lead to various waveforms.[4][9][12]

Gymnotiforms

In gymnotiforms, electrocytes differ between wave-type and pulse-type electric fish. In wave-type fish, electrocytes are in a tubular form. In pulse fish the electrocytes tend to be flattened disks. The electrocytes also form columns, but unlike the shorter size of electric organ in mormyrids, gymnotiforms have long electric organs that extend throughout almost the entire longitudinal body length. Also different from the stalk system in mormyrids, stalks in gymnotiforms only make one type of innervation at the posterior side of electrocyte. Pulse-type gymnotifoms generally show a higher complexity than the wave-type fish. For instance, their electrocytes can be either cylindrical or drum-shaped with stalks innervating from either posterior or anterior side. Another important difference is that, unlike mormyrids or wave-type gymnotiforms, electrocytes of pulse-type gymnotiforms are not homogenous along the long electric organ that traverses the fish body. Different parts of the electric organs of some gymnotoiforms are innervated differently or may have different cellular firing properties.

Apternotids, a member of the wave-type gymnotiforms, is different from all other electric fish as being the only family possessing neurogenic electrocytes. Electric organ of Apternotids is derived from neurons; more specifically, they are formed from the axons of spinal electromotor neurons. Such structure eliminates one [synapse|synaptic gap] between spinal electromotor neuron and the myogenic electrocytes, which might contribute to Apternotids' highest EOD frequency (>2000 Hz) among electric fish.[9]

Signals

Types of signals

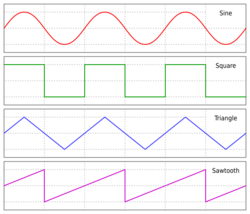

There are two types of signals generated by electric fish: pulse-type and wave-type. A pulse-type EOD is characterized by discrete EOD pulse separated by relatively long silent intervals much longer than the discharges; contrarily, a wave-type EOD has its firing period and silence period approximately the same in length, and therefore a continuous signal with quasi-sinusoidal waveform is formed. Among the mormyrids and gymnotiforms, both pulse-type and wave-type fish are consistent within grouped by families.[13]

Physical properties of signals

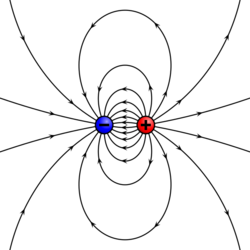

Electric field

Electric fish generate an electrostatic field shaped like a dipole, with field lines describing a curved arc from positive pole to negative. The electric field signals differ from other communicating modes of communication such as sound or optical, which use signals that propagate as waves. While sound waves for acoustic communication or light waves (electromagnetic waves) for visual communications all propagate, electric signals do not (it is different from electromagnetic waves). As an electric field, the signal magnitude decreases in accordance with the inverse square law, which makes the signal sending and formation an energy-costly process. Electric fish match the impedance of their electric organ to the conductivity of water in order to achieve minimum energy lost, and the final result is electric signals traveling for at most a few meters. Although electric fish are limited to a short communication range, the signals remain uncorrupted by echo and reverberation, which affects sound and light. Deterioration of waves includes reflection, refraction, absorption, interference, and so on. As a result, the temporal features, which are very important for electric fish signals, remain constant during transmission.[14]

Active space

When transmitting electric signals in aquatic environment, the physical and chemical nature of the surroundings can make big differences to signal transmission. Environmental factors that might impose influences include solute concentration, temperature, and background electrical noise (lightning or artificial facilities), etc. To understand the effectiveness of electric signal transmission, it is necessary to define the term "active space-" the area/ volume within which a signal can elicit responses from other organisms. The active space of an electric fish normally has an ellipsoid shape due to the arrangement of dipoles formed by its electric organs. While both electric communication and electrolocation rely on signals generated by electric organs, electrocommunication has an active space tenfold larger than electrolocation because of the extreme sensitivity of tuberous electrocommunication receptors.[15]

One of the biggest factors that affect active space size will be the water conductance mediated by solute concentration in the water. It has been shown that mormyrids have adapted its optimal active range in lower-conductivity habitats. One natural phenomenon that supports such theory is that, many species spawn during the time when rivers/ lakes have the lowest conductivity due to heavy rains. Having bigger active space in water with low conductivity will therefore benefit mating and courting.[16] One other explanation tested by Kim and Moller is that, having smaller active space during dry season when mating is not occurring accommodates crowded social spacing without unnecessary signal transmission between individuals.[4]

Frequency and waveform

Electric fish communicate with electric signals that possess two main qualities - frequency and waveform. The information in waveform is embedded in the electric organ discharge (EOD) itself, which is determined and fixed by the anatomy and physiology of the electric organ. EOD waveform, in some species, changes with developmental stages. Frequency of EODs and interval duration between them are called sequence of pulse intervals (SPI), which are controlled by the command interneurons in the midbrain and medulla, as stated under electric organs. Alteration in SPI produces widely varying social signals among electric fish during mating, warning, or identifying. These two properties (waveform/EOD and frequency/SPI) are used by both wave and pulse type fish for recognition and communication.[17]

EOD frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit time. Here, EOD frequency is referred to the firing rate of an electric fish. Wave-type fish carry out species recognition by mediating their EOD frequencies, which include their baseline firing frequencies and modulation of frequencies that results in rising, falling, warbling, and cessations of EOD frequencies. For an example, some gymnotiform species use "chirps," a sudden frequency increase, during courtship.

EOD waveform

Waveform is the shape and form of a wave. Each species of electric fish has their distinct EOD waveform. Pulse-type fish conduct species recognition by paying attention to the differences of EOD waveform, which include properties such as: EOD duration, number of phases, and form of the phases. Meanwhile, some indirect properties hidden in waveform are also used by pulse-type fish: amplitude gradient, duration ratios of phases, and the order and signs of phases.

Differences and changes in signals

Electric fish normally possess a baseline frequency and waveform of their signals, alteration in both qualities occur all the time- among different species, sex, development stages, and dominance status. While different alterations occur to signal generations based on the fish's identities, the level and types of alteration is limited by the fish's own sensory system, which is biased to sense signals that have similar frequency to its own discharge frequency.[6]

Signals and sex

As electric fish mature, some taxa develop differences in EOD between males and females (i.e. sexual dimorphism). Typically, male electric fish have lower EOD frequency and longer EOD duration than females; among males, the dominant and largest fish generally possesses the lowest frequency. For example, measurements made in Sternopygus marucus (Hagedorn, 1986) showed that males usually generate EOD at about 80 Hz, while females generate EOD at around 150 Hz. Such differences in EOD between the sexes can be traced back to changes in the action potential in electrocytes. As electric fish mature from the juvenile stage, male fish grow larger with longer and thicker tails, which might result in larger electric organs that generate lower frequency EODs.[18][19] One of the physiological factors that have been proven to contribute to the sexual dimorphism of EODs is the level of teleost hormone- androgen 11-keto-testosterone (11-KT) and estrogen. Experiments shown that by injecting 11-KT into female electric fish, not only did their EOD waveforms and frequencies become closer to that of the males, but their tuberous electroreceptors were also modified to be able to detect signals according to the newly transformed EOD properties. However, when estrogen was applied, the EODs of male electric fish gradually became closer to the female EODs.[6][20]

Sexual dimorphism in EOD waveforms and frequencies also imposes an influence on active space size. Using Sternopygus marucus as example, males and emit frequencies almost half those of females (80 Hz cf. 150 Hz). However, since most electroreceptors are tuned to signal frequencies that are closer to the receivers' own frequency, the difference in EOD frequency results in a different ability of electric fish to sense signals from either sex, which further leads to different active space sizes. As measured in Sternopygus marucus by Hagedorn, male fish can only detect females in a range of 6 cm, while female fish can detect a male fish in a much bigger range of 39 cm. This active space size difference is hypothesized to give female fish a better probability of getting closer to potential mates and select an individual to mate with.[4][18][19]

Signals and development stages

Studies done on both gymnotiforms and mormyrids have shown that there are species in both groups that have significant EOD changes from larvae to adult. Gymnotiform larvae all have EODs that are simple, monophasically similar to a single period cosine function, and formed with a very broad spectrum at lower frequency range. It is observed that, as the larvae mature, the frequency spectrum decreases, the discharge waveform becomes sharper, and more complex waveforms that may consist of multiple phases gradually replace the simple larval EOD.[21]

For the myogenic fish, this change in signal waveform occurs with the initial larval electrocytes fusing together forming new electrocytes with different shapes, along with redistribution of ion-gated channels, formation of new extracellular structures on the electrocytes, etc. Some pulse fish also develop accessory electric organs located on other parts of the body; these extra electric organs further play a role in adding phases to the EODs. For the only neurogenic fish known so far, apteronotids, EOD changes during the developmental process seemed to be more dramatic than that of the myogenic fish, which might indicate that neurogenic electrocytes are more easily prone to modifications. Similar with the myogenic fish, apteronotids has its electric organ formed by myocytes. As apteronotids matures, new neurogenic electrocytes derived from spinal motoneurons replace the myogenic electrocytes.[10]

There were two hypotheses proposed for the reason why electric signals were modified during the fish's development stages. Firstly, as stated above, the fish's electroreceptors are usually tuned to a specific range of frequencies. Therefore, to make effective communication, it is necessary for the electric fish to narrow the broad frequency spectrum of the larval EOD. Secondly, it is known that the electroreceptors of catfish, gymnotiforms, and most pre-teleost fish are tuned to lower frequencies. Therefore, keeping the low frequency of larval EOD will increase the risk of being detected by predators.[6]

Signals and dominance status

Measurements have shown that typically, male electric fish that's dominating usually has lower EOD frequency and longer EOD duration. An experiment has shown that, when two males are placed in the same fish tank, both fish enhance their EOD in the first short period of time. However, after leaving the fish in a dark period (mimicking night time), the male with higher EOD amplitude, which is also usually the male with bigger body size, will further enhance its EOD; on the contrary, the male with smaller body size/ smaller EOD does not enhance its EOD.[22]

Signals and the environment

Signals may differ due features of the environment. Pulse-type EODs are better suited for slow-flowing drainages with high levels of vegetation because they can detect a wider range of frequency than wave-type signals, allowing for detection of finer detail in a more crowded environment. In contrast, wave-type EODs are better suited for fast-flowing waters and low vegetation because the rate of the signal is faster than pulse-type, enabling better detection of rapidly moving objects. There is therefore a trade-off between wave-type and pulse-type EODs, where wave-type signals have high temporal detection but low spatial detection, and pulse-type signals have the opposite.[23]

Special signals

In electric communication, there are some distinct types of signals that serve special purposes such as courting or aggression. Examples of these special EODs include: "rasps", "chirps" and "smooth acceleration". Rasp is a burst of pulses at a relatively constant frequency performed by some species during courtship. Chirp is a rapid increase or decrease in frequency. Smooth acceleration is a period of tens to hundreds of milliseconds that EOD rate increases but in a smooth way. Due to law of conservation of energy, the amplitude of the EOD might lower for a few percent, but the overall changes in waveform and amplitude Is small. Male gymnotiforms emit these accelerated signals during aggression and courtship. In the fish studied, if courtship goes well and proceeds to spawning, male electric fish starts to use another special type of EOD- the chirp. Chirp also lasts for tens to hundreds milliseconds; however, the increase in frequency was so high that electrocytes could not recover soon enough, and therefore, chirps has a very small amplitude and a waveform deviated from the original waveform.[17][24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Masashi Kawasaki. The electric fish. [1] Retrieved 12/3/2011

- ↑ Map of Life, 2011

- ↑ "Electroreception in the Guiana dolphin (Sotalia guianensis)". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 279 (1729): 663–8. February 2012. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1127. PMID 21795271.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Moller, P. (1995) Electric Fishes: History and Behavior. Chapman & Hall

- ↑ Electroreception and Communication in Fishes / Bernd Kramer - Stuttgart; Jena ;Lübeck ; Ulm : G. Fischer, 1996. Progress in Zoology ; Vol. 42.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Ladich, Friedrich. 2006. Communication in fishes. Enfield, NH: Science Publishers

- ↑ Carl Hopkins. Electroreception. [2] Retrieved 12/5/2011

- ↑ Zakon, H. (1986). The electroreceptive periphery. In Electroreception, eds. T. H. Bullock and W. F. Heiligenberg), pp. 103-156. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Masashi Kawasaki Chapter 7: Physiology of Tuberous Electrosensory Systems. In: Theodore H. Bullock, Carl D. Hopkins, Arthur N. Popper and Richard R. Fay. 2005 (eds), Electroreception. New York: Springer.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bennett MVL (1971) Electric organs. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ (eds), Fish Physiology. London: Academic Press

- ↑ "Philip K. Stoddard, Electric Signals and Electric Fishes. 2009". http://www2.fiu.edu/~efish/publications/Stoddard_Electric_Signals_2009.pdf.

- ↑ Hopkins, CD, Design features for electric communication Journal of Experimental Biology Vol. 202, 10, 1999, p. 1217

- ↑ Stoddard PK. (2002) Electric signals: predation, sex, and environmental constraints. Advances in the Study of Behavior

- ↑ Hopkins, CD, Temporal structure of non-propagated electric communication signals brain behavior and evolution Vol. 28, 1986, p. 43 [3]

- ↑ Bossert, WH, The analysis of olfactory communication among animals. Journal of Theoretical Biology. Vol. 5, 3, 1963, p. 443

- ↑ Squire, A; Moller, P. Effects of water conductivity on electrocommunication in the weak-electric fish Brienomyrus niger (Mormyriformes)animal behaviourVol. 30, 2, 1982, p. 375

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hopkins, C.D., Neuroethology of electric communicationannual review of neuroscienceVol. 11, 1, 1988, p. 497

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hopkins, C. D. (1972). Sex differences in electric signaling in anelectric fish. Science 176

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hagedorm, M.(1986) The ecology, courtship and mating of gymnotiform electric fish. (eds. Bullock, T. H.Heiligenberg, W.), Wiley, NY

- ↑ Bass, A. H.; Hopkins, C.D., Shifts in frequency tuning of electroreceptors in androgen-treated mormyrid fish, Journal of Comparative Physiology, Volume 155, Number 6, 713-724, doi:10.1007/BF00611588

- ↑ Emergence and development of the electric organ discharge in the mormyrid fish, Pollimyrus isidori, G. W. Max Westby and Frank Kirschbaum, Journal of Comparative Physiology A, Volume 122, Number 2, 251-271, doi:10.1007/BF00611894

- ↑ Franchina,C.R.; Salazar, V.L.; Volmar, C. H, and Stoddard, P.K., Plasticity of the electric organ discharge waveform of male Brachyhypopomus pinnicaudatus. II. Social effects Journal of Comparative Physiology B Vol. 187, 1, 2001, p. 45

- ↑ Crampton, William G. R. (2019). "Electroreception, electrogenesis and electric signal evolution" (in en). Journal of Fish Biology 95 (1): 92–134. doi:10.1111/jfb.13922. ISSN 1095-8649. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jfb.13922.

- ↑ Carl Hopkins, Behavioral Evidence for Species Recognition [4], Retrieved 12/6/2011

External links

- A video of courtship and pawning behavior between a male and female Brienomyrus brachyistius can be seen here.

- Methods for listening to electric fish at home.