Biology:Onager

| Onager | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Persian onager (Equus hemionus onager) at Rostov-on-Don Zoo, Russia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Subgenus: | Asinus |

| Species: | E. hemionus[1]

|

| Binomial name | |

| Equus hemionus[1] Pallas, 1775

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Onager range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Equus onager (Boddaert, 1785) | |

The onager (/ˈɒnədʒər/;[3] Equus hemionus /ˈɛkwəs hɪˈmaɪənəs/),[4][5] also known as hemione or Asiatic wild ass,[6] is a species of the family Equidae native to Asia. A member of the subgenus Asinus, the onager was described and given its binomial name by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1775. Six subspecies have been recognized, two of which are extinct.

The Asiatic wild ass is larger than the African wild ass at about 290 kg (640 lb) and 2.1 m (6.9 ft) (head-body length). They are reddish-brown or yellowish-brown in color and have broad dorsal stripe on the middle of the back. Unlike most horses and donkeys, onagers have never been domesticated. They are among the fastest mammals, as they can run as fast as 64 km/h (40 mph) to 70 km/h (43 mph). The onager is closely related to the African wild ass, as they both shared the same ancestor. The kiang, formerly considered a subspecies of Equus hemionus, is generally considered a distinct species,[7] however, this has been questioned, with some genomic studies finding the kiang to be nested within the diversity of Equus hemionus.[8]

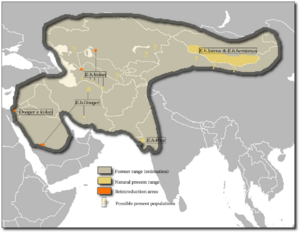

The onager formerly had a wider range from southwest and central to northern Asian countries, such as Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Afghanistan, Russia , and Siberia; the prehistoric European wild ass subspecies ranged through Europe until the Bronze age.[9] During early 20th century, the species lost most of its ranges in the Middle East and Eastern Asia. Today, onagers live in deserts and other arid regions of Iran, Pakistan , India , and Mongolia, including in Central Asian hot and cold deserts of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and China .[1]

Other than deserts, it lives in grasslands, plains, steppes, and savannahs. Like many other large grazing animals, the onager's range has contracted greatly under the pressures of poaching and habitat loss.[6] Previously listed as Endangered, the onager has been classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List in 2015.[2] Of the five subspecies, one is extinct, two are endangered, and two are near threatened; its status in China is not well known.[6] Persian onagers are currently being reintroduced in the Middle East as replacements for the extinct Syrian wild ass in the Arabian Peninsula, Israel and Jordan.

Etymology

The specific name is from the Ancient Greek Ancient Greek:, from Ancient Greek:, and Ancient Greek:; thus, 'half-donkey' or mule. The term onager comes from the ancient Greek ὄναγρος, again from Ancient Greek:, and Ancient Greek:.

The species was commonly known as Asian wild ass, in which case the term onager was reserved for the E. h. onager subspecies,[6] more specifically known as the Persian onager. Until this day, the species share the same name, onager.

Taxonomy and evolution

The onager is a member of the subgenus Asinus, belonging to the genus Equus and is classified under the family Equidae. The species was described and given its binomial name Equus hemionus by German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1775.

The Asiatic wild ass, among Old World equids, existed for more than 4 million years. The oldest divergence of Equus was the onager followed by the zebras and onwards.[10] A new species called the kiang (E. kiang), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as E. hemionus kiang, but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct species, having diverged from the closest relative of the Mongolian wild ass's ancestor less than 500,000 years ago.[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subspecies

Five widely recognized subspecies of the onager include:[6]

| Subspecies | Image | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pallas, 1775 | Northern China , eastern Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Siberia |

| ||

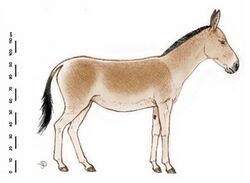

|

Groves and Mazák, 1967 | One of the largest subspecies of onager. It is 200–250 cm (79–98 in) long, 100–140 cm (39–55 in) tall at the withers, and weighs 200–240 kg (440–530 lb). Male onagers are larger than the females. | Northeastern Iran, Northern Afghanistan, western China, Kazakhstan, southern Siberia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine , Northern Mongolia, and Uzbekistan | finschi (Matschie, 1911) | |

|

Boddaert, 1785 | Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan . | |||

|

Lesson, 1827 | Southern Afghanistan, India , southeast Iran and Pakistan | indicus (Sclater, 1862) | ||

|

Geoffroy, 1855 | Smallest subspecies, also the smallest form of Equidae | Western Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey | syriacus (Milne-Edwards, 1869) | |

|

Regalia, 1907 | Formerly thought to be a distinct species, shown to be a subspecies of Onager by genetic studies in 2017.[8] | Europe, Western Asia |

A sixth possible subspecies, the Gobi khulan (E. h. luteus,[2] also called the chigetai[11] or dziggetai) has been proposed, but may be synonymous with E. h. hemionus.

Debates over the taxonomic identity of the onager occurred until 1980. (As of 2015), four living subspecies and one extinct subspecies of the Asiatic wild ass have been recognized. The Persian onager was formerly known as Equus onager, as it was thought to be a distinct species.

Characteristics

Onagers are the most horse-like of wild asses. They are short-legged compared with horses, and their coloring varies depending on the season. They are generally reddish-brown in color during the summer, becoming yellowish-brown or grayish-brown in the winter. They have a black stripe bordered in white that extends down the middle of the back. The belly, the rump, and the muzzle are white in most onagers, except for the Mongolian wild ass that has a broad black dorsal stripe bordered with white.

Onagers are larger than donkeys at about 200 to 290 kg (440 to 640 lb) in size and 2.1 to 2.5 m (6.9 to 8.2 ft) in head-body length. Male onagers are usually larger than females.

Evolution

The genus Equus, which includes all extant equines, is believed to have evolved from Dinohippus via the intermediate form Plesippus. One of the oldest species is Equus simplicidens, described as zebra-like with a donkey-shaped head. The oldest fossil to date is about 3.5 million years old from Idaho, USA. The genus appears to have spread quickly into the Old World, with the similarly aged Equus livenzovensis documented from western Europe and Russia.[12]

Molecular phylogenies indicate the most recent common ancestor of all modern equids (members of the genus Equus) lived around 5.6 (3.9–7.8) million years ago (Mya). Direct paleogenomic sequencing of a 700,000-year-old middle Pleistocene horse metapodial bone from Canada implies a more recent 4.07 Mya for the most recent common ancestor within the range of 4.0 to 4.5 Mya.[13] The oldest divergencies are the Asian hemiones (subgenus E. (Asinus), including the kulan, onager, and kiang), followed by the African zebras (subgenera E. (Dolichohippus), and E. (Hippotigris)). All other modern forms including the domesticated horse (and many fossil Pliocene and Pleistocene forms) belong to the subgenus E. (Equus) which diverged about 4.8 (3.2–6.5) Mya.[10]

Distribution and habitat

The onagers' favored habitats consist of desert plains, semideserts, oases, arid grasslands, savannahs, shrublands, steppes, mountainous steppes, and mountain ranges. The Turkmenian kulan and Mongolian wild asses are known to live in hot and colder deserts. The IUCN estimates about 28,000 mature individuals in total remain in the wild.[2]

During the late Pleistocene era around 40,000 years ago, the Asiatic wild ass ranged widely across Europe and in southwestern to northeastern Asia. The onager has been regionally extinct in Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, and southern regions of Siberia.

The Mongolian wild ass lives in deserts, mountains, and grasslands of Mongolia and Inner Mongolian region of northern China. A few live in northern Xinjiang region of northwestern China, most of which live mainly in Kalamaili Nature Reserve. It is the most common subspecies, but its populations have drastically decreased to a few thousand due to years of poaching and habitat loss in East Asia. The Gobi Desert is the onager's main stronghold. It is regionally extinct in eastern Kazakhstan, southern Siberia, and the Manchurian region of China.

The Indian wild ass was once found throughout the arid parts and desert steppes of northwest India and Pakistan, but about 4,500 of them are found in a few very hot wildlife sanctuaries of Gujarat. The Persian onager is found in two subpopulations in southern and northern Iran. The larger population is found at Khar Turan National Park. However, it is extirpated from Afghanistan. The Turkmenian kulan used to be widespread in central to north Asia. However, it is now found in Turkmenistan and has been reintroduced in southern Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Biology and behavior

Asiatic wild asses are mostly active at dawn and dusk, even during the intense heat.

Social structure

Like most equids, onagers are social animals. Stallions are either solitary or live in groups of two or three. The males have been observed holding harems of females, but in other studies, the dominant stallions defend territories that attract females. Differences in behaviour and social structure likely are the result of changes in climate, vegetation cover, predation, and hunting.

The social behavior of the Asian wild ass can vary widely, depending on different habitats and ranges, and on threats by predators including humans. In Mongolia and Central Asia (E. h. hemionus and E. h. kulan), an onager stallion can adopt harem-type social groups, with several mares and foals in large home areas in the southwest, or in territory-based social groups in the south and southeast. Also, annual large hikes occur, covering 4.5 km2 (1.7 sq mi) to 40 km2 (15 sq mi), where hiking[clarification needed] in summer is more limited than in the winter. Onagers also occasionally form large group associations of 450 to 1,200 individuals, but this usually only occurs in places with food or water sources. As these larger groups dissolve again within a day, no overarching hierarchy apart from the ranking of the individual herds seems to exist. Young male onagers also frequently form "bachelor groups" during the winter. Such a lifestyle is also seen in the wild horse, the plains zebras (E. quagga) and mountain zebras (E. zebra).

Southern populations of onagers in the Middle East and South Asia tend to have a purely territorial life, where areas partly overlap. Dominant stallions have home ranges of 9 km2 (3.5 sq mi), but they can also be significantly larger. These territories include food and rest stops and permanent or periodic water sources. The waters are usually at the edge of a coalfield[clarification needed] and not in the center. Mares with foals sometimes find themselves in small groups, in areas up to 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi), which overlap with those of the other groups and dominant stallions. Such features are also seen among Grévy's zebras (E. grevyi) and the African wild asses.

Reproduction

The Asian wild ass is sexually mature at two years old, and the first mating usually takes place at three to four years old.

Breeding is seasonal, and the gestation period of onagers is 11 months; the birth lasts a little more than 10 minutes. Mating and births occur from April to September, with an accumulation from June to July. The mating season in India is in the rainy season. The foal can stand and starts to nurse within 15 to 20 minutes. Females with young tend to form groups of up to five females. During rearing, a foal and dam remain close, but other animals and her own older offspring are displaced by the dam. Occasionally, stallions in territorial wild populations expel the young to mate with the mare again. Wild Asian wild asses reach an age of 14 years, but in captivity, they can live up to 26 years.

Diet

Like all equids, onagers are herbivorous mammals. They eat grasses, herbs, leaves, fruits, and saline vegetation when available, but browse on shrubs and trees in drier habitats. They have also been seen feeding on seed pods such as Prosopis and breaking up woody vegetation with their hooves to get at more succulent herbs growing at the base of woody plants.

During the winter, onagers also eat snow as a substitute for water. When natural water sources are unavailable, the onager digs holes in dry riverbeds to reach subsurface water. The water holes dug by the onagers are often subsequently visited by domestic livestock, as well as other wild animals. Water is also found in the plants on which the onagers feed.

During spring and summer in Mongolia, the succulent plants of the Zygophyllaceae form an important component of the diet of the Mongolian wild ass.

Predation

The onager is preyed upon by predators such as Persian leopards and striped hyenas. A few cases of onager deaths due to predation by leopards have been recorded in Iran. Though leopards do not usually feed on equids as in Africa, this may be because Persian leopards are larger and strong enough to prey on Asiatic wild asses.[14][15]

In the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, Asiatic lions and tigers were the main predators of onagers. They were also formerly preyed upon by dholes, Asiatic cheetahs, and possibly bears, though they may have mostly preyed only on onager foals.[citation needed] In India, mugger crocodiles can be great threats to onagers during migratory river crossings.[citation needed]

Currently, the main predator for onagers are gray wolves. However, like most equids, they are known to have antipredator behaviour. Groups of stallions cooperate and try to chase off predators. If threatened, onagers defend themselves and violently kick at the incoming predator.[citation needed]

Threats

The greatest threat facing the onager is poaching for meat and hides, and in some areas for use in traditional medicine. It[clarification needed] is one of the highest threats for the Mongolian wild ass. The extreme isolation of many subpopulations also threatens the species, as genetic problems can result from inbreeding. Overgrazing by livestock reduces food availability, and herders also reduce the availability of water at springs. The cutting down of nutritious shrubs and bushes exacerbates the problem. Furthermore, a series of drought years could have devastating effects on this beleaguered species.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are also major threats to the onager, a particular concern in Mongolia as a result of the increasingly dense network of roads, railway lines, and fences required to support mining activities.

The Asiatic wild ass is also vulnerable to diseases. A disease known as the "South African horse sickness" caused a major decline to the Indian wild ass population in the 1960s. However, the subspecies is no longer under threat to such disease and is continuously increasing in number.

Conservation

Various breeding programs have been started for the onager subspecies in captivity and in the wild, which increases their numbers to save the endangered species. The species is legally protected in many of the countries in which it occurs. The priority for future conservation measures is to ensure the protection of this species in particularly vulnerable parts of its range, to encourage the involvement of local people in the conservation of the onager, and to conduct further research into the behavior, ecology, and taxonomy of the species.

Two onager subspecies, the Persian onager and the Turkmenian kulan are being reintroduced to their former ranges, including in other regions the Syrian wild ass used to occur in the Middle East. The two subspecies have been reintroduced to the wild of Israel since 1982, and had been breeding hybrids there,[16] whilst the Persian onager alone has been reintroduced to Jordan and the deserts of Saudi Arabia.

Relationship with humans

Onagers are notoriously difficult to tame. Equids were used in ancient Sumer to pull wagons c. 2600 BC, and then chariots on the Standard of Ur, c. 2550 BC. Clutton-Brock (1992) suggests that these were donkeys rather than onagers on the basis of a "shoulder stripe".[17] However, close examination of the animals (equids, sheep and cattle) on both sides of the piece indicate that what appears to be a stripe may well be a harness, a trapping, or a joint in the inlay.[18][19] Genetic testing of skeletons from that era shows that they were kungas, a cross between an onager and a donkey.

In literature

In the Hebrew Bible there is a reference to the onager in Job 39:5:

Who freed the wild donkey, loosed the ropes of the onager?—Job 39:5[20]

In La Peau de Chagrin by Honoré de Balzac, the onager is identified as the animal from which comes the ass' skin or shagreen of the title.[citation needed]

A short poem by Ogden Nash also features the onager:

Have you ever harked to the jackass wild, which scientists call the onager?

It sounds like the laugh of an idiot child, or a hepcat on a harmonager.

But do not laugh at the jackass wild, for there is method in his he-haw:

for with maidenly blush, and accent mild, the jenny-ass answers "She-haw".

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 632. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14100020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kaczensky, P.; Lkhagvasuren, B.; Pereladova, O.; Hemami, M.; Bouskila, A. (2020). "Equus hemionus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T7951A166520460. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T7951A166520460.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/7951/166520460. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Longman, J.C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3 ed.). Pearson Education ESL. ISBN 978-1405881173.

- ↑ "Equus". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Equus.

- ↑ "Hemionus". https://www.websters1913.com/words/Hemionus.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Asiatic Wild Ass Equus hemionus". IUCN. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. http://data.iucn.org/themes/ssc/sgs/equid/ASWAss.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ryder, O.A.; Chemnick, L.G. (1990). "Chromosomal and molecular evolution in Asiatic wild asses". Genetica 83 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1007/BF00774690. PMID 2090563.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bennett, E. Andrew; Champlot, Sophie; Peters, Joris; Arbuckle, Benjamin S.; Guimaraes, Silvia; Pruvost, Mélanie; Bar-David, Shirli; Davis, Simon J. M. et al. (2017-04-19). Janke, Axel. ed. "Taming the late Quaternary phylogeography of the Eurasiatic wild ass through ancient and modern DNA" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (4): e0174216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174216. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28422966. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1274216B.

- ↑ Crees, Jennifer J.; Turvey, Samuel T. (2014). "Holocene extinction dynamics of Equus hydruntinus, a late-surviving European megafaunal mammal". Quaternary Science Reviews 91: 16–29. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.03.003. Bibcode: 2014QSRv...91...16C.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Weinstock, J. (2005). "Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Pleistocene horses in the New World: a molecular perspective". PLOS Biology 3 (8): e241. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030241. PMID 15974804.

- ↑ Ian Lauder Mason (2002). Porter, Valerie. ed. Mason's World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types, and Varieties (5th ed.). Wallingford: CABI. ISBN 0-85199-430-X.

- ↑ Azzaroli, A. (1992). "Ascent and decline of monodactyl equids: a case for prehistoric overkill". Ann. Zool. Finnici 28: 151–163. http://www.sekj.org/PDF/anzf28/anz28-151-163.pdf.

- ↑ Orlando, L. et al. (4 July 2013). "Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse". Nature 499 (7456): 74–8. doi:10.1038/nature12323. PMID 23803765. Bibcode: 2013Natur.499...74O.

- ↑ Sanei, A., Zakaria, M., Hermidas, S. (2011). "Prey composition in the Persian leopard distribution range in Iran". Asia Life Sciences Supplement 7 (1): 19−30. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258220097.

- ↑ Persian Leopard Newsletter No.4. Wildlife.ir. 2010. http://www.yemenileopard.org/files/cms/reports/No._4_September_and_October_2010.pdf. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Saltz, D. (1995). "Population dynamics of a reintroduced Asiatic wild ass (Equus Hemionus) herd". Ecological Applications 5 (2): 327–335. doi:10.2307/1942025.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1992). Horse Power: A History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies. Boston, Massachusetts, US: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-40646-9.

- ↑ Heimpel, Wolfgang (1968). Tierbilder in der Sumerische Literatur. Italy: Studia Pohl 2.

- ↑ Maekawa, K. (1979). "The Ass and the Onager in Sumer in the Late Third Millennium B.C.". Acta Sumerologica (Hiroshima) I: 35–62.

- ↑ Job 39:5: Common English Bible translation, also in New King James Version

- Duncan, P., ed (1992). Zebras, Asses, and Horses: An Action Plan for the Conservation of Wild Equids. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. ISBN 9782831700526. OCLC 468402451.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- "Ass"—Encyclopædia Britannica

- Equus hemionus bibliography at The Biodiversity Heritage Library

Wikidata ☰ Q180960 entry

|