Biology:List of lilioid families

Template:Featured list is only for Wikipedia:Featured lists.

The lilioid monocots are a group of 33 interrelated families of flowering plants.[lower-alpha 1] They generally have tepals (indistinguishable petals and sepals) similar to those on the true lilies (Lilium).[5][6][7] Like other monocots[lower-alpha 2] they usually have a single embryonic leaf (cotyledon) in their seeds, scattered vascular systems, leaves with parallel veins, flower parts in multiples of three, and roots that can develop in more than one place along the stems.[11]

The lilioids can be subdivided into five orders: Asparagales, Dioscoreales, Liliales, Pandanales and Petrosaviales. Asparagales is roughly tied with Poales for the most diverse monocot order and includes Orchidaceae, the largest flowering plant family, with more than 26,000 species.[1][12] Plants in Dioscoreales, such as yams, usually have inflorescences with glandular hairs.[13] In Liliales, plants often have elliptical leaves with up to seven primary veins, inflorescences at the tips of stems, and nectar-producing glands on the tepals.[14] Pandanales includes fragile, non-herbaceous and drought-tolerant species, with leaves often arranged in three vertical rows.[15][16] Petrosaviales includes species with spirally arranged leaves, nectar-producing glands, and racemes (unbranched inflorescences with short flower stalks).[17]

Glossary

From the glossary of botanical terms:

- annual: a plant species that completes its life cycle within a single year or growing season

- basal: attached close to the base (of a plant or an evolutionary tree diagram)

- climber: a vine that leans on, twines around or clings to other plants for vertical support

- glandular hair: a hair tipped with a secretory structure

- herbaceous: not woody; usually green and soft in texture

- perennial: not an annual or biennial

- woody: hard and lignified; not herbaceous[18]

The APG IV system is the fourth in a series of plant taxonomies from the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group.[3]

Families

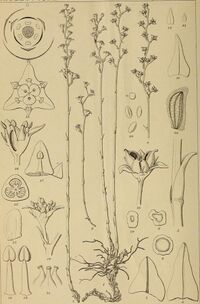

| Family and a common name[5][lower-alpha 3] | Type genus and etymology[lower-alpha 4] | Total genera; global distribution | Description and uses | Order[20] | Type genus images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alstroemeriaceae (Inca-lily family) |

Alstroemeria was named for Clas Alströmer (1736–1794).[21][22] | 4 genera, in Australia, New Zealand and central and southern parts of the Americas[21][23] | Generally rhizomatous herbaceous perennials, erect or climbing. Alstroemeria ligtu and Bomerea edulis are cultivated as food crops, and Alstroemeria flowers are bred by horticulturists for the cut-flower trade.[21][24][lower-alpha 5] | Liliales | |

| Amaryllidaceae (onion family) |

Amaryllis was the name of a mythical Greek shepherdess.[25][26] | 69 genera, almost worldwide[27][28] | Herbaceous perennials growing from fleshy rhizomes or bulbs. Allium has been consumed as food or seasoning since the Bronze Age or earlier; today it includes onions, shallots, leeks and garlic. Many bulbs in this family are commercially important in the bulb trade, and Hippeastrum and Narcissus are popular in the cut-flower trade.[27][29] | Asparagales | |

| Asparagaceae (hyacinth family) |

Asparagus comes from a Latin plant name.[30][31] | 120 genera, worldwide, except in the eastern Amazon basin and some deserts[32][33] | Trees, shrubs or herbaceous plants that grow in soil or rarely on other plants. Asparagus and Agave have long histories of use in food and drink, while sisal is used for rope-making. Many species are grown as ornamentals or cut-flowers.[32][34] | Asparagales | |

| Asphodelaceae (daylily family) |

Asphodelus is from a Greek plant name.[35][36] | 41 genera, worldwide, except in North America[37][38] | Climbing, shrubby, tree-like or herbaceous perennials. The sap of Aloe vera has widespread use in cosmetics and food. Aloe, Asphodeline, Bulbine, Eremurus, Gasteria, Haworthia and Kniphofia are popular ornamentals.[37][39] | Asparagales | |

| Asteliaceae (pineapple-grass family) |

Astelia is from the Greek for "columnless" (or "trunkless").[40][41] | 3 genera, scattered in the Southern Hemisphere, mostly[42][43] | Herbaceous tufted perennials that grow in soil, or sometimes on other plants. Leaves of Astelia grandis are used in woven handicrafts in New Zealand.[42] | Asparagales | |

| Blandfordiaceae (Christmas-bells family) |

Blandfordia was named for George Spencer-Churchill, 5th Duke of Marlborough (1766–1840).[44] | 1 genus, in Eastern Australia, including Tasmania[44][45] | Herbaceous tufted perennials growing from thickened rhizomes. The sole genus is bred and cultivated for the cut-flower trade.[44] | Asparagales | |

| Boryaceae (pincushion-lily family) |

Borya was named for Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent (1778–1846).[46][47] | 2 genera, in Australia[48][49] | Perennial clumpy shrubs[48] | Asparagales | |

| Burmanniaceae (bluethreads family) |

Burmannia was named for Johannes Burman (1707–1780).[50][51] | 14 genera, in the tropics worldwide, the United States, Japan, and Oceania[50][52] | Generally blue, purple or white herbaceous plants. Some species rely on fungi and organic material rather than photosynthesis.[50][53][lower-alpha 5] | Dioscoreales | |

| Campynemataceae (green-mountainlily family) |

Campynema is from the Greek for "bent thread".[54][55] | 2 genera, in Tasmania and New Caledonia[54][56] | Rhizomatous herbaceous perennials, with just one or a few leaves clustered at the plant's base[54] | Liliales | |

| Colchicaceae (naked-ladies family) |

Colchicum was named for Colchis (on the Black Sea, in modern-day Georgia).[57][58] | 15 genera, in a variety of temperate and tropical habitats, although not in South America[59][60] | Herbaceous or slightly woody perennials, erect or climbing, with rhizomes, tubers or corms. Most species are toxic, and sometimes deadly to livestock. Colchicine (from Colchicum) is used in the study of cell division.[59][61] | Liliales | |

| Corsiaceae (ghost-flower family) |

Corsia was named for Bardo Corsi Salviati (1844–1907), an Italian nobleman.[62][63] | 3 genera, in Southern South America, southern China and Oceania[64][65] | Rhizomatous or tuberous herbaceous perennials, relying on fungi and organic matter instead of photosynthesis[64][66] | Liliales | |

| Cyclanthaceae (Panama hat family) |

Cyclanthus is from the Greek for "circle of flowers".[67][68] | 12 genera, in the tropical Americas[69][70] | Perennials growing in soil or on other plants. Straw from Carludovica palmata is woven into baskets and Panama hats (which originated in Ecuador).[69][71] | Pandanales | |

| Dioscoreaceae (yam family) |

Dioscorea was named for Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 – c. 90).[72][73] | 4 genera, in the tropics and some temperate regions[72][74] | Rhizomatous or tuberous plants, mostly vines. Yam species were first domesticated around 11,000 years ago, independently in West Africa and southern China.[72][75] | Dioscoreales | |

| Doryanthaceae (gymea-lily family) |

Doryanthes is from the Greek for "spear of flowers".[76] | 1 genus, in Eastern Australia[77][78] | One genus of large tufted perennials. Their nectar helps sustain honeyeaters.[77] | Asparagales | |

| Hypoxidaceae (stargrass family) |

Hypoxis comes from a Greek plant name.[79][80] | 5 genera, throughout the tropics and in a few temperate zones in North America, Japan and Australia[81][82] | Herbaceous perennials. The thickened rhizomes are covered with dead leaf sheaths and soft, short hairs.[81][83] | Asparagales | |

| Iridaceae (iris family) |

Iris comes from the Greek for "goddess of the rainbow".[84][85] | 69 genera, worldwide, except in deserts[86][87] | Generally herbaceous perennials growing from bulbs, rhizomes or corms. Crocus sativus is grown commercially for the spice saffron. Many plants in this family are bred and cultivated as ornamentals, especially Freesia, Gladiolus, Iris and Ixia.[86][88] | Asparagales | |

| Ixioliriaceae (tartar-lily family) |

Ixiolirion comes from the genus Ixia and the Greek word for "lily".[89][90] | 1 genus, in semi-desert zones from Egypt to Central Asia[91][92] | Herbaceous perennials with corms and erect stems. Ixiolirion tataricum bulbs are sold as ornamentals.[91] | Asparagales | |

| Lanariaceae (lambtails family) |

Lanaria is from the Greek for "woolly".[93] | 1 genus, in Fynbos shrubland in southern South Africa[93][94] | One species, a herbaceous perennial with erect, leafy rhizomes[93] | Asparagales | |

| Liliaceae (lily family) |

Lilium comes from a Latin plant name.[95][96] | 15 genera, in the Northern Hemisphere, particularly in temperate zones[97][98] | Herbaceous perennials with erect stems that grow from bulbs or rhizomes. Tulips (Tulipa) and true lilies (Lilium) are mainly bred for the cut-flower trade, but bulbs of some species are also consumed as food.[97][99] | Liliales | |

| Melanthiaceae (wake robin family) |

Melanthium is from the Greek for "dark flowers".[100][101] | 14 genera, in the non-tropical Northern Hemisphere, and in Peru, Taiwan and the Himalayas[102][103] | Herbaceous perennials with rhizomes and bulbs or other underground organs. Paris japonica has the largest known genome of any living thing.[102] | Liliales | |

| Nartheciaceae (bog asphodel family) |

Narthecium comes from a Greek plant name.[104][105] | 5 genera, in parts of the United States, northern South America and Eurasia[106][107] | Herbaceous rhizomatous perennials.[106][108] Narthecium ossifragum has been used for dyeing.[106] | Dioscoreales | |

| Orchidaceae (orchid family) |

Orchis comes from the Greek for "testicle", from the shape of the paired root tubers of many Mediterranean species.[1][109][110] | 707 genera, worldwide, especially in the tropics[1][111] | Largely herbaceous plants that generally grow in soil or on other plants. Orchids are the largest family of vascular plants, with more than 26,000 species and 100,000 recorded cultivars. Vanilla is derived from the fermentation of Vanilla planifolia. Cattleya, Cymbidium, Oncidium, Phalaenopsis, Paphiopedilum and Vanda are commonly grown ornamentals.[1][112] | Asparagales | |

| Pandanaceae (screwpine family) |

Pandanus was named for the Malay plant pandan, a curry spice.[113][114][115] | 5 genera, scattered throughout the Old World tropics[113][116] | Woody vines, shrubs or palm-like trees, often with aerial roots. Pandanus conoideus is an important crop in Papua New Guinea. Other species of the genus are consumed in Indonesia, Micronesia and New Zealand.[113][117] | Pandanales | |

| Petermanniaceae (Petermann's-vine family) |

Petermannia was named for August Heinrich Petermann (1822–1878), a cartographer.[118] | 1 genus, in Eastern Australia[119][120] | One species, a rhizomatous perennial with tendrils, woody vines and prickly stems[119] | Liliales | |

| Petrosaviaceae (oze-so family) |

Petrosavia was named for Pietro Savi (1811–1871), an Italian professor of botany.[121][122] | 2 genera, in several eastern Asian countries[123][124] | Herbaceous rhizomatous plants, sometimes relying on fungi and organic matter instead of photosynthesis[123] | Petrosaviales | |

| Philesiaceae (Chilean-bellflower family) |

Philesia comes from the Greek for "loving".[125][126] | 2 genera, in Chile[127][128] | Climbers or shrubs, found in beech forests in the cooler parts of Chile. Lapageria rosea is the country's national flower.[127] | Liliales | |

| Ripogonaceae (supplejack family) |

Ripogonum comes from the Greek for "wicker knees", referring to the joints on tangled stalks.[129][130] | 1 genus, in Oceania[131][132] | Woody rhizomatous evergreen shrubs or vines. Stems have been used for handicrafts and in construction.[131] | Liliales | |

| Smilacaceae (catbrier family) |

Smilax comes from a Greek plant name.[133][134] | 1 genus, found throughout the tropics and in some temperate zones[135][136] | Perennial vines or shrubs, often with prickly stems. Some Smilax species have been used in root beer and other soft drinks.[135][137] | Liliales | |

| Stemonaceae (baibu family) |

Stemona comes from the Greek for "stamens".[138][139] | 4 genera, in the southern United States, tropical and subtropical Asia, and Oceania[138][140] | Herbaceous perennials, usually twining or erect. They rely on ants for seed propagation.[138] | Pandanales | |

| Tecophilaeaceae (Chilean-crocus family) |

Tecophilaea was named for Tecophila Billotti, a 19th-century Italian botanical artist.[141][142] | 9 genera, in Sub-Saharan Africa, California and Chile[141][143] | Herbaceous perennials sprouting from tubers or rounded corms[141][144] | Asparagales | |

| Triuridaceae (threetails family) |

Triuris comes from the Greek for "three tails".[15][145] | 8 genera, scattered throughout the tropics[146] | White, yellow, purple or red rhizomatous plants, relying on fungi and organic material rather than photosynthesis[15][147] | Pandanales | |

| Velloziaceae (baboon-tail family) |

Vellozia was named for Joaquim Velloso de Miranda (1733–1815), a Brazilian clergyman and plant collector.[148][149] | 6 genera, widespread in South America and Africa (except North Africa), with some species in Asia[150][151] | Woody or herbaceous perennials. They can reach 6 m (20 ft) in height.[150][152] | Pandanales | |

| Xeronemataceae (Poor-Knights-lily family) |

Xeronema is from the Greek for "dry thread".[153][154] | 1 genus, in Poor Knights and other New Zealand islands, and New Caledonia[153][155] | Stemless tufted evergreen perennials[153] | Asparagales |

See also

Notes

- ↑ The taxonomy (classification) in this list follows Plants of the World (2017)[2] and the fourth Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system.[3] Total counts of genera for each family come from Plants of the World Online.[4] (See the POWO license.) Extinct taxa are not included.

- ↑ The lilioids and the commelinids together form a clade of the monocots, that is, a subgroup consisting of all the descendants of a theoretical ancient ancestor. The monocots, including the grass, palm, banana, ginger, asparagus, pineapple, sedge and onion families, are the plants responsible for most of the global agricultural output.[8][9][10]

- ↑ Each family's formal name ends in the Latin suffix -aceae and is derived from the name of a genus that is or once was part of the family.[19]

- ↑ Some plants were named for naturalists (unless otherwise noted).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Some taxonomists prefer to place some of Burmanniaceae's genera in two additional families, named Thismiaceae and Taccaceae, and some of Alstroemeriaceae's genera in one additional family, named Luzuriagaceae.[3]

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 151–159.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016.

- ↑ POWO.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 131–174.

- ↑ Zomlefer et al. 2001, Abstract

- ↑ Meerow 2002, p. 37.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 10,642.

- ↑ Givnish et al. 2010, p. 585.

- ↑ Royal Botanic Gardens.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Asparagales.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Dioscoreales.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Liliales.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 136.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Pandanales.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Petrosaviales.

- ↑ Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 638–670.

- ↑ ICN, art. 18.

- ↑ Stevens 2023, Summary of APG IV.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ IPNI, Alstroemeriaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Alstroemeriaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Alstroemeriaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ IPNI, Amaryllidaceae, Type.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ POWO, Amaryllidaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Amaryllidaceae, Flora of West Tropical Africa.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 54.

- ↑ IPNI, Asparagaceae, Type.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 171–174.

- ↑ POWO, Asparagaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Asparagaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ USDA, Asphodelaceae, Type.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 168.

- ↑ POWO, Asphodelaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Asphodelaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ Bayton 2020, p. 51.

- ↑ USDA, Asteliaceae, Type.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ POWO, Asteliaceae.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 160.

- ↑ POWO, Blandfordiaceae.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. B-79.

- ↑ USDA, Boryaceae, Type.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ POWO, Boryaceae.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ IPNI, Burmanniaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Burmanniaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Burmanniaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 141.

- ↑ USDA, Campynemataceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Campynemataceae.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 100.

- ↑ IPNI, Colchicaceae, Type.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ POWO, Colchicaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Colchicaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. C-63.

- ↑ IPNI, Corsiaceae, Type.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ POWO, Corsiaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Corsiaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 110.

- ↑ IPNI, Cyclanthaceae, Type.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 139.

- ↑ POWO, Cyclanthaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Cyclanthaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ IPNI, Dioscoreaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Dioscoreaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Dioscoreaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 123.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ POWO, Doryanthaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 172.

- ↑ IPNI, Hypoxidaceae, Type.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ POWO, Hypoxidaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Hypoxidaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 177.

- ↑ IPNI, Iridaceae, Type.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ POWO, Iridaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Iridaceae, Flora of West Tropical Africa.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 177.

- ↑ USDA, Ixioliriaceae, Type.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 164.

- ↑ POWO, Ixioliriaceae.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ POWO, Lanariaceae.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 191.

- ↑ IPNI, Liliaceae, Type.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ POWO, Liliaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Liliaceae, Flora of West Tropical Africa.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 204.

- ↑ IPNI, Melanthiaceae, Type.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ POWO, Melanthiaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 215.

- ↑ IPNI, Nartheciaceae, Type.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ POWO, Nartheciaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Nartheciaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 225.

- ↑ IPNI, Orchidaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Orchidaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Orchidaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 140.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 229.

- ↑ USDA, Pandanaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Pandanaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Pandanaceae, Flora of West Tropical Africa.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. P-29.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 143.

- ↑ POWO, Petermanniaceae.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. P-32.

- ↑ IPNI, Petrosaviaceae, Type.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ POWO, Petrosaviaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 238.

- ↑ IPNI, Philesiaceae, Type.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 147.

- ↑ POWO, Philesiaceae.

- ↑ Stearn 2002, p. 260.

- ↑ USDA, Ripogonaceae, Type.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ POWO, Ripogonaceae.

- ↑ Coombes 2012, p. 275.

- ↑ IPNI, Smilacaceae, Type.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ POWO, Smilacaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Smilacaceae, Flora of Tropical East Africa.

- ↑ 138.0 138.1 138.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 138.

- ↑ IPNI, Stemonaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Stemonaceae.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 141.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ IPNI, Tecophilaeaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Tecophilaeaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Tecophilaeaceae, Flora of Zambesiaca.

- ↑ IPNI, Triuridaceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Triuridaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Triuridaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2018, p. V-11.

- ↑ IPNI, Velloziaceae, Type.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, p. 137.

- ↑ POWO, Velloziaceae.

- ↑ POWO, Velloziaceae, Neotropikey.

- ↑ 153.0 153.1 153.2 Christenhusz, Fay & Chase 2017, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ USDA, Xeronemataceae, Type.

- ↑ POWO, Xeronemataceae.

References

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2016). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 181 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/boj.12385.

- Bayton, Ross (2020). The Gardener's Botanical: An Encyclopedia of Latin Plant Names. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20017-0.

- Burkhardt, Lotte (2018) (in German) (pdf). Verzeichnis eponymischer Pflanzennamen – Erweiterte Edition. Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.3372/epolist2018. ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5. https://doi.org/10.3372/epolist2018. Retrieved January 1, 2021. See the Creative Commons license.

- Christenhusz, Maarten; Fay, Michael Francis; Chase, Mark Wayne (2017). Plants of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Vascular Plants. Chicago, Illinois: Kew Publishing and The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-52292-0.

- Coombes, Allen (2012). The A to Z of Plant Names: A Quick Reference Guide to 4000 Garden Plants. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-60469-196-2.

- Givnish, Thomas J.; Ames, Mercedes; McNeal, Joel R.; McKain, Michael R.; Steele, P. Roxanne; dePamphilis, Claude W.; Graham, Sean W.; Pires, J. Chris et al. (December 27, 2010). "Assembling the Tree of the Monocotyledons: Plastome Sequence Phylogeny and Evolution of Poales". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 97 (4): 584–616. doi:10.3417/2010023. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/172229. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- IPNI (2022). "International Plant Names Index". London, Boston and Canberra: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and the Australian National Botanic Gardens. https://www.ipni.org.

- Meerow, A.W. (2002). "The new phylogeny of the Lilioid Monocotyledons". Acta Horticulturae 570 (570): 31–45. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2002.570.2. http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/2962/PDF.

- POWO (2019). "Plants of the World Online". London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/. See their terms-of-use license.

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (2010). "Monocots I: General Alismatids & Lilioids". London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. http://www.kew.org/science/directory/teams/MonocotsI/index.html.

- Stearn, William (2002). Stearn's Dictionary of Plant Names for Gardeners. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36469-5.

- Stevens, P.F. (2023). "Angiosperm Phylogeny Website". Missouri Botanical Garden. http://www.mobot.org/mobot/research/APWeb.

- Turland, N. J., ed. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017 (electronic ed.). Glashütten: International Association for Plant Taxonomy. https://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/pages/main/art_18.html. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- "USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Plant Germplasm System". Beltsville, Maryland: National Germplasm Resources Laboratory. 2022. https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomysearch?t=family.

- Zomlefer, Wendy B.; Williams, Norris H.; Whitten, W. Mark; Judd, Walter S. (September 2001). "Generic circumscription and relationships in the tribe Melanthieae (Liliales, Melanthiaceae), with emphasis on Zigadenus: evidence from ITS and trnL-F sequence data". American Journal of Botany 88 (9): 1657–1669. doi:10.2307/3558411. PMID 21669700. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2307/3558411?sid=nlm%3Apubmed. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

|