Biology:Magnolia grandiflora

| Southern magnolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Magnoliaceae |

| Genus: | Magnolia |

| Section: | Magnolia sect. Magnolia |

| Species: | M. grandiflora

|

| Binomial name | |

| Magnolia grandiflora | |

| |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

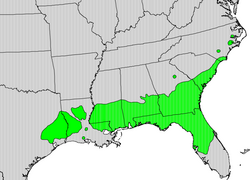

Magnolia grandiflora, commonly known as the southern magnolia or bull bay, is a tree of the family Magnoliaceae native to the Southeastern United States, from Virginia to central Florida, and west to East Texas.[5] Reaching 27.5 m (90 ft) in height, it is a large, striking evergreen tree, with large, dark-green leaves up to 20 cm (7 3⁄4 in) long and 12 cm (4 3⁄4 in) wide, and large, white, fragrant flowers up to 30 cm (12 in) in diameter.

Although endemic to the evergreen lowland subtropical forests on the Gulf and South Atlantic coastal plain, M. grandiflora is widely cultivated in warmer areas around the world. The timber is hard and heavy, and has been used commercially to make furniture, pallets, and veneer.

Description

Magnolia grandiflora is a medium to large evergreen tree which may grow 120 ft (37 m) tall.[6] It typically has a single stem (or trunk) and a pyramidal shape.[7] The leaves are simple and broadly ovate, 12–20 cm (4 3⁄4–7 3⁄4 in) long and 6–12 cm (2 1⁄4–4 3⁄4 in) broad,[7] with smooth margins. They are dark green, stiff, and leathery, and often scurfy underneath with yellow-brown pubescence.

The large, showy, lemon citronella-scented flowers are white, up to 30 cm (11 3⁄4 in) across and fragrant, with six to 12 petals with a waxy texture, emerging from the tips of twigs on mature trees in late spring.[8]

Flowering is followed by the rose-colored fruit, ovoid polyfollicle, 7.5–10 cm (3–3 7⁄8 in) long, and 3–5 cm (1 1⁄4–2 in) wide.[9]

Exceptionally large trees have been reported in the far Southern United States. The national champion is a specimen in Smith County, Mississippi, that stands 37 m (121 ft). Another record includes a 35-m-high specimen from the Chickasawhay District, De Soto National Forest, in Mississippi, which measured 17.75 ft (5.4 m) in circumference at breast height, from 1961, and a 30-m-tall tree from Baton Rouge, which reached 18 ft in circumference at breast height.[9]

Taxonomy

M. grandiflora was one of the many species first described by Linnaeus in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae in 1759,[10] basing his description on the earlier notes of Miller. He did not select a type specimen. Its specific epithet is derived from the Latin words grandis "big", and flor- "flower".[11] The genus name Magnolia honors Pierre Magnol, a French botanist.[8]

M. grandiflora is most commonly known as southern magnolia, a name derived from its range in the Southern United States. Many broadleaved evergreen trees are known as bays for their resemblance to the leaves of the red bay (Persea borbonia), with this species known as the bull bay for its huge size or alternatively because cattle have been reported eating its leaves. Laurel magnolia,[11] evergreen magnolia,[9] large-flower magnolia or big laurel are alternative names.[12] The timber is known simply as magnolia.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Southern magnolias are native to the Southeastern United States, from Virginia south to central Florida, and then west to East Texas. The tree is found on the edges of bodies of water and swamps, in association with sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), water oak (Quercus nigra), and black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica). In more sheltered habitats, it grows into a large tree, but can be a low shrub when found on coastal dunes.[13] It is killed by summer fires, and is missing from habitats that undergo regular burning.[14]

In Florida, it is found in a number of different ecological areas that are typically shady and have well-draining soils; it is also found in hummocks, along ravines, on slopes, and in wooded floodplains.[15] Despite preferring sites with increased moisture, it does not tolerate inundation.[9] It grows on sandhills in maritime forests, where it is found growing with live oaks and saw palmetto (Serenoa repens).[14] In the eastern United States, it has become an escapee, and has become naturalized in the tidewater area of Virginia and locally in other areas outside of its historically natural range.[16][17]

Ecology

M. grandiflora can produce seed by 10 years of age, although peak seed production is achieved closer to 25 years of age. Around 50% of seeds can germinate, and they are spread by birds and mammals.[9] Squirrels, possums, quail, and turkey are known to eat the seeds.[18]

Cultivation and uses

Plant collector Mark Catesby, the first in North America, brought M. grandiflora to Britain in 1726, where it entered cultivation and overshadowed M. virginiana, which had been collected a few years earlier. It had also come to France, the French having collected it in the vicinity of the Mississippi River in Louisiana.[19] It was glowingly described by Philip Miller in his 1731 work The Gardeners' Dictionary.[20] One of the earliest people to cultivate it in Europe was Sir John Colliton of Exeter in Devon; scaffolding and tubs surrounded his tree, where gardeners propagated its branches by layering, the daughter plants initially selling for five guineas each (but later falling to half a guinea).[20]

It is often planted in university campuses and allowed to grow into a large tree, either with dependent branches, or with the lower branches removed to display the bare trunks. It is also espaliered against walls, which improves its frost hardiness.[11] It is often planted ornamentally in urban areas due to its resistance to air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide[21]

United States cultivation

M. grandiflora is a very popular ornamental tree throughout its native range in the coastal plain of the Gulf/South Atlantic states. Grown for its attractive, shiny green leaves and fragrant flowers, it has a long history in the Southern United States. Many large and very old specimens can be found in the subtropical port cities such as Houston; New Orleans; Mobile, Alabama; Jacksonville, Florida; Savannah, Georgia; Charleston, South Carolina; and Wilmington, North Carolina. M. grandiflora is the state tree of Mississippi and the state flower of Louisiana. The species is also cultivated as far north as coastal areas of New Jersey, Connecticut, Long Island, New York, and Delaware, and in much of the Chesapeake Bay region in Maryland, and eastern Virginia. On the West Coast, it can be grown as far north as the Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada area, though cooler summers on the West Coast slow its growth compared to the East Coast.[11] In the interior of the US, some of the cold-hardy cultivars have flourished as far north as Louisville, Kentucky and Cincinnati, Ohio, where a sizable population exists. Farther north, few known long-term specimens are found due to the severe winters, and/or lack of sufficient summer heat. Seeds may promote health and prevent diseases like high blood pressure, heart disturbances and epilepsy.[22]

M. grandiflora is also grown in parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America, as well as parts of Asia.[11]

Until early 2018, an iconic southern magnolia planted by President Andrew Jackson nearly 200 years earlier grew near the South Portico of the White House.[23] It was reputedly planted as a seedling taken from Jackson's plantation, The Hermitage in Tennessee. It was the oldest tree on the White House grounds and was so famous that it was for decades pictured on the back of the $20 bill as part of a view of the South Front.[24] There was a tradition of giving cuttings or seedlings grown from the tree: Reagan gave a cutting to his Chief of Staff Howard Baker upon his retirement, and Michelle Obama donated a seedling to the "people's garden" of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[24] Since the 1940s, when the tree suffered a gash that caused a large section of its trunk to rot, the tree had been supported by metal poles and cables. In 2017, it was decided on the advice of the National Arboretum to cut down and remove the magnolia because the trunk was in an extremely fragile condition and the supports had been compromised. Offshoots from the Jackson magnolia have been saved, grown up to 10ft and one was planted[25] at the place of the original tree. [24]

It is recommended for seashore plantings in areas that are windy but have little salt spray.[26] The foliage will bronze, blotch, and burn in severe winters at the northern limits of cultivation, especially when grown in full winter sun,[27] but most leaves remain until they are replaced by new foliage in the spring. In climates where the ground freezes, winter sun appears to do more damage than the cold. In the Northern Hemisphere, the south side of the tree experiences more leaf damage than the north side. Two extremes are known, with leaves white underneath and with leaves brown underneath. The brown varieties are claimed to be more cold hardy than the white varieties, but this does not appear to be proven as yet. Once established, the plants are drought tolerant, and the most drought tolerant of all the Magnolia species.[27]

The leaves are heavy and tend to fall year round from the interior of the crown and form a dense cover over the soil surface,[27] and they have been used in decorative floral arrangements.[28] The leaves have a waxy coating that makes them resistant to damage from salt and air pollution.[27]

In the United States, southern magnolia, along with sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana) and cucumbertree (Magnolia acuminata), is commercially harvested. Lumber from all three species is simply called magnolia, which is used in the construction of furniture, boxes, pallets, venetian blinds, sashes, and doors, and used as veneers. Southern magnolia has yellowish-white sapwood and light to dark brown heartwood tinted yellow or green. The usually straight-grained wood has uniform texture with closely spaced rings. The wood is ranked moderate in heaviness, hardness, and stiffness, and moderately low in shrinkage, bending, and compression strength; it is ranked moderately high in shock resistance.[29] Its use in the Southeastern United States has been supplanted by the availability of harder woods.[30]

Cultivars

Over 150 cultivars have been developed and named, although only 30 to 40 of these still exist and still fewer are commercially propagated and sold.[31] Most plants in nurseries are propagated by cuttings, resulting in more consistent form in the various varieties available.[32] Many older cultivars have been superseded by newer ones and are no longer available.[33] Some cultivars have been found to be more cold hardy, they include:

- 'Bracken's Brown Beauty' was developed by Ray Bracken of Easley, South Carolina, in the late 1960s and patented in 1985.[31] It is a popular cultivar that has survived long-term in West Virginia, New Jersey, and Long Island, NY. This cultivar grows in a dense and compact pattern, with narrow, medium-sized, glossy leaves. Flowers measure 5–6 in (13–15 cm).

- 'Edith Bogue' was brought to the coastal plain of New Jersey from Florida in the 1920s. The original tree sent to Edith A. Bogue from Florida helped to establish cold-hardy specimens in the Middle Atlantic states from Delaware to coastal Connecticut. Once established, 'Edith Bogue' has been known to have only minor spotting and margin burn on the leaf in temperatures as low as −5 °F (−21 °C). With a vigorous classic pyramidal shape, this cultivar grows to 35 ft with a 15-ft spread. The leaves are large and deep green, but lack the brown indumentum on their undersides which make other cultivars so distinctive.

- 'Angustifolia', developed in France in 1825, has narrow, spear-shaped leaves 20 cm (7.9 in) long by 11 cm (4.3 in) wide, as its name suggests.[32]

- 'Exmouth' was developed in the early 18th century by John Colliton in Devon. It is notable for its huge flowers, with up to 20 petals, and vigorous growth. Erect in habit, it is often planted against walls. The leaves are green above and brownish underneath.[34] The flowers are very fragrant and the leaves are narrow and leathery.[35]

- 'Goliath' was developed by Caledonia Nurseries of Guernsey, and has a bushier habit and globular flowers of up to 30 cm (12 in) diameter. Long-flowering, it has oval leaves which lack the brownish hair underneath.[34]

- 'Little Gem', a dwarf cultivar, is grown in more moderate climates, roughly from New Jersey, Maryland and the Virginias southward. Originally developed in 1952 by Steed's Nursery in Candor, North Carolina, it is a slower-growing form with a columnar shape which reaches around 4.25 m (13.9 ft) high and 1.2 m (3.9 ft) wide. Flowering heavily over an extended period in warmer climate, it bears medium-sized, cup-shaped flowers, and has elliptic leaves 12.5 cm (4.9 in) long by 5 cm (2.0 in) wide.[34] It flowers relatively quickly after planting compared with other cultivars.[36]

- "Victoria" is a form grown in the Pacific Northwest that is reportedly hardy to -12 F. It has a more open habit and shiny dark green leaves with brown undersides.[31]

Other commonly grown cultivars include:

- 'Ferruginea' has dark-green leaves with rust-brown undersides.[35]

- 'Southern Charm' is a dwarf form that grows into a bushy shrub with a pyramidal shape up to 20–25 ft high and 10 ft wide. It has dark green shiny leaves 3-6 in long and 2-4 in wide with brown undersides. It is also known as 'Teddy Bear',[31] for the fuzzy brown undersurface of the leaves.[36]

Chemistry

Magnolia grandiflora contains phenolic constituents shown to possess significant antimicrobial activity. Magnolol, honokiol, and 3,5′-diallyl-2′-hydroxy-4-methoxybiphenyl exhibited significant activity against Gram-positive and acid-fast bacteria and fungi.[37] The leaves contain coumarins and sesquiterpene lactones.[38] The sesquiterpenes are known to be costunolide, parthenolide, costunolide diepoxide, santamarine, and reynosin.[39]

Gallery

-

Magnolia grandiflora (southern magnolia) – a large tree at Hemingway, South Carolina

-

Bark on trunk

-

Southern magnolia blossom & bud

-

Southern magnolia foliage and flower

-

A cluster of leaves

-

Southern magnolia bud

-

Inside the flower

-

Seed cluster of M. grandiflora

-

Southern magnolia blossom

-

From below

-

Martin Johnson Heade: Magnolia

-

Before the opening act

-

Flower in three stages of blossoming

-

Foliage 'Bracken's Brown Beauty'

-

Mature fruit

References

- ↑ Khela, S. (2014). "Magnolia grandiflora". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T193948A2291865. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T193948A2291865.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/193948/2291865. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "NatureServe Explorer". https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.146090/Magnolia_grandiflora.

- ↑ "Magnolia grandiflora". https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/magnolia-grandiflora/.

- ↑ "Plants of the World Online". https://powo.science.kew.org/?.

- ↑ "Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center - The University of Texas at Austin". https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=MAGR4.

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 144

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Zion, Robert L. (1995). Trees for architecture and landscape. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-471-28524-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=aaKTWJG4-iQC&pg=PA224.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Magnolia grandiflora - Plant Finder". https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=282515&isprofile=1&basic=magnolia%20grandiflora.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Maisenhelder, Louis C. (1970). "Magnolia". American Woods FS-245. US Dept. of Agriculture. http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/usda/amwood/245magno.pdf.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1758) (in la). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. 2 (10th revised ed.). Holmiae: (Laurentii Salvii). p. 1082. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/587001.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Callaway, p. 99

- ↑ Coladonato, Milo (1991). "Magnolia grandiflora". Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/maggra/all.html.

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 143

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Whitney, Eleanor Noss; Rudloe, Anne; Jadaszewski, Erick (2004). Priceless Florida: Natural Ecosystems and Native Species. Pineapple Press (FL). p. 36. ISBN 978-1-56164-308-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=NXrygt0m50oC&pg=PA36.

- ↑ Nelson, Gil; Marvin, Jr Cook (1994). The Trees of Florida: A Reference and Field Guide (Reference and Field Guides (Paperback)). Pineapple Press (FL). p. 17. ISBN 978-1-56164-055-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wzmo7cHvhZkC&pg=PA17.

- ↑ "Magnolia grandiflora in Flora of North America @". Efloras.org. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=200008470. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- ↑ http://bonap.net/MapGallery/County/Magnolia%20grandiflora.png Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2015. North American Plant Atlas. (http://bonap.net/napa ). Chapel Hill, N.C. [maps generated from Kartesz, J.T. 2015. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). (in press)].

- ↑ Halls, L. K. 1977. Southern magnolia/Magnolia grandiflora L. In Southern fruit-producing woody plants used by wildlife. p. 196-197. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report SO-16. Southern Forest Experiment Station, New Orleans, LA.

- ↑ Aitken, Richard (2008). Botanical Riches: Stories of Botanical Exploration. Melbourne, Victoria: Miegunyah Press: State Library of Victoria. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-522-85505-0.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gardiner, p. 18

- ↑ Outcalt, Kenneth (1990). Magnolia grandiflora L. southern magnolia. Silvics of North America, 2. pp. 445-448.

- ↑ Lee, Yang Deok (2011-01-01), Preedy, Victor R.; Watson, Ronald Ross; Patel, Vinood B., eds., "Chapter 86 - Use of Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) Seeds in Medicine, and Possible Mechanisms of Action", Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention (San Diego: Academic Press): pp. 727–732, ISBN 978-0-12-375688-6, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123756886100866, retrieved 2023-10-04

- ↑ Kate Bennett (2017-12-27). "Exclusive: Iconic White House tree to be cut down". CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/26/politics/white-house-jackson-magnolia-south-facade/index.html.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Sarah Kaplan (2017-12-26). "White House to cut back magnolia tree planted by Andrew Jackson". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2017/12/26/white-house-to-cut-down-magnolia-tree-planted-by-andrew-jackson/.

- ↑ "However disappointing the removal of the Jackson Magnolia, the silver lining of its demise is that White House groundskeepers were prepared. For several months, at an undisclosed greenhouse-like location nearby, healthy offshoots of the tree have been growing, tended to with care and now somewhere around eight to 10 feet tall. CNN has learned the plan is that another Jackson Magnolia, born directly from the original, will soon be planted in its place, for history to live on." Bennett, CNN report, as note 2

- ↑ Bush-Brown, Louise Carter; Bush-Brown, James; Irwin, Howard S. (1996). America's garden book. New York: Macmillan USA. pp. 537. ISBN 0-02-860995-6. https://archive.org/details/americasgardenbo00bush_0/page/537.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Sternberg, Guy; Wilson, James; Wilson, Jim (2004). Native trees for North American landscapes: from the Atlantic to the Rockies. Portland: Timber Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-88192-607-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=qOq5v4fd1kcC&pg=PA268.

- ↑ Callaway, p. 13

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Wood. Skyhorse Publishing. 17 May 2007. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-1-60239-057-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=mUGSaiTsBAIC&pg=PT8.

- ↑ Callaway, p. 14

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Dirr, Michael A. (2011). Dirr's Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 478–481. ISBN 978-0-88192-901-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=OCVFA1hm8qUC&q=%27Southern+Charm%27+magnolia+%27Teddy+Bear&pg=PA936.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Gardiner, p. 145

- ↑ Callaway, p. 100

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Gardiner, p. 147

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Brickell, Christopher (1989). The American Horticultural Society encyclopedia of garden plants. New York: Macmillan. pp. 51. ISBN 0-02-557920-7. https://archive.org/details/americanhorticul00chri_0/page/51.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Wolfe, Judy. "Little Gem vs. Teddy Bear Magnolia Trees". Leaf Group. https://www.hunker.com/12459868/little-gem-vs-teddy-bear-magnolia-trees.

- ↑ Antimicrobial activity of phenolic constituents of magnolia grandiflora L. Alice M. Clark, Arouk S. El-Feraly, Wen-Shyong Li, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, August 1981, Volume 70, Issue 8, pages 951–952, doi:10.1002/jps.2600700833

- ↑ Coumarins and sesquiterpene lactones from Magnolia grandiflora leaves. Yang MH, Blunden G, Patel AV, O'Neill MJ and Lewis JA, Planta medica, 1994, vol. 60, no 4, pages 390-390, INIST:11250251

- ↑ Isolation and characterization of the sesquiterpene lactones costunolide, parthenolide, costunolide diepoxide, santamarine, and reynosin from Magnolia grandiflora L. Farouk S. El-Feraly and Yee-Ming Chan, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, March 1978, Volume 67, Issue 3, pages 347–350, doi:10.1002/jps.2600670319

Cited texts

- Callaway, Dorothy Johnson (1994). The world of magnolias. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-236-6.

- Gardiner, Jim (2000). Magnolias: A Gardener's Guide. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-446-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern magnolia. |

- United States Department of Agriculture Plants Profile for Magnolia grandiflora (southern magnolia)

- Magnolia grandiflora images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

Wikidata ☰ Q161116 entry

|