Pyramid (geometry)

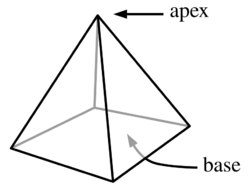

In geometry, a pyramid (from grc πυραμίς (puramís))[1][2] is a polyhedron formed by connecting a polygonal base and a point, called the apex. Each base edge and apex form a triangle, called a lateral face. It is a conic solid with a polygonal base. Many types of pyramids can be found by determining the shape of bases, or cutting off the apex. It can be generalized into higher dimension, known as hyperpyramid. All pyramids are self-dual.

Definition

A pyramid is a polyhedron that may be formed by connecting a polygonal base and a point, called the apex. Each base edge and apex form an isosceles triangle, called a lateral face.[3] The edges connected from the polygonal base's vertices to the apex are called lateral edges.[4] Historically, the definition of a pyramid has been described by many mathematicians in ancient times. Euclides in his Elements defined a pyramid as a solid figure, constructed from one plane to one point. The context of his definition was vague until Heron of Alexandria defined it as the figure by putting the point together with a polygonal base.[5]

A prismatoid is defined as a polyhedron where its vertices lie on two parallel planes, with its lateral faces are triangles, trapezoids, and parallelograms.[6] Pyramids are classified as prismatoid.[7]

Classification and types

A right pyramid is a pyramid where the base is circumscribed about the circle and the altitude of the pyramid meets at the circle's center.[8] This pyramid may be classified based on the regularity of its bases. A pyramid with a regular polygon as the base is called a regular pyramid.[9] For the pyramid with an n-sided regular base, it has n + 1 vertices, n + 1 faces, and 2n edges.[10] Such pyramid has isosceles triangles as its faces, with its symmetry is Cnv, a symmetry of order 2n: the pyramids are symmetrical as they rotated around their axis of symmetry (a line passing through the apex and the base centroid), and they are mirror symmetric relative to any perpendicular plane passing through a bisector of the base.[11][12] Examples are square pyramid and pentagonal pyramid, a four- and five-triangular faces pyramid with a square and pentagon base, respectively; they are classified as the first and second Johnson solid if their regular faces and edges that are equal in length, and their symmetries are C4v of order 8 and C5v of order 10, respectively. A tetrahedron or triangular pyramid is an example that has four equilateral triangles, with all edges equal in length, and one of them considered as the base. Because the faces are regular, it is an example of a Platonic solid and deltahedra, and it has tetrahedral symmetry.[13][14] A pyramid with the base as circle is known as cone.[15] Pyramids have the property of self-dual, meaning their duals are the same as vertices corresponding to the edges and vice versa.[16] Their skeleton may be represented as the wheel graph.[17]

A right pyramid may also have a base with an irregular polygon. Examples are the pyramids with rectangle and rhombus as their bases. These two pyramids have the symmetry of C2v of order 4.

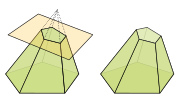

The type of pyramids can be derived in many ways. The base regularity of a pyramid's base may be classified based on the type of polygon, and one example is the pyramid with regular star polygon as its base, known as the star pyramid.[18] The pyramid cut off by a plane is called a Lua error: not enough memory.truncated pyramid; if the truncation plane is parallel to the base of a pyramid, it is called a frustum.

Mensuration

The surface area is the total area of each polyhedra's faces. In the case of a pyramid, its surface area is the sum of the area of triangles and the area of the polygonal base.

The volume of a pyramid is the one-third product of the base's area and the height. Given that is the base's area and is the height of a pyramid. Mathematically, the volume of a pyramid is:[19]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. The volume of a pyramid was recorded back in ancient Egypt, where they calculated the volume of a square frustum, suggesting they acquainted the volume of a square pyramid.[20]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. The formula of volume for a general pyramid was discovered by Indian mathematician Aryabhata, where he quoted in his Aryabhatiya that the volume of a pyramid is incorrectly the half product of area's base and the height.[21]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

Generalization

The hyperpyramid is the generalization of a pyramid in n-dimensional space. In the case of the pyramid, one connects all vertices of the base, a polygon in a plane, to a point outside the plane, which is the peak. The pyramid's height is the distance of the peak from the plane. This construction gets generalized to n dimensions. The base becomes a (n − 1)-polytope in a (n − 1)-dimensional hyperplane. A point called the apex is located outside the hyperplane and gets connected to all the vertices of the polytope and the distance of the apex from the hyperplane is called height.[22]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

The n-dimensional volume of a n-dimensional hyperpyramid can be computed as follows: Here Vn denotes the n-dimensional volume of the hyperpyramid. A the (n − 1)-dimensional volume of the base and h the height, that is the distance between the apex and the (n − 1)-dimensional hyperplane containing the base A.[22]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

References

- ↑ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, πυραμίς, https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dpurami%2Fs.

- ↑ The word meant "a kind of cake of roasted wheat-grains preserved in honey"; the Egyptian pyramids were named after its form. See Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1261.

- ↑ Cromwell, Peter R. (1997), Polyhedra, Cambridge University Press, p. 13, https://archive.org/details/polyhedra0000crom/page/13/mode/2up?view=theater.

- ↑ Smith, James T. (2000), Methods of Geometry, John Wiley & Sons, p. 98, ISBN 0-471-25183-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=B0khWEZmOlwC&pg=PA98.

- ↑ Heath, Thomas (1908), Euclid: The Thirteen Books of the Elements, 3, Cambridge University Press, p. 268, https://archive.org/details/euclids-elements-vol.-3/page/268/mode/1up?view=theater.

- ↑ Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2015), A Mathematical Space Odyssey: Solid Geometry in the 21st Century, Mathematical Association of America, p. 85, https://books.google.com/books?id=FEl2CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA85.

- ↑ Grünbaum, Branko (1997), "Isogonal Prismatoids", Discrete & Computational Geometry 18: 13–52, doi:10.1007/PL00009307.

- ↑ Polya, G. (1954), Mathematics and Plausible Reasoning: Induction and analogy in mathematics, Princeton University Press, p. 138, https://books.google.com/books?id=-TWTcSa19jkC&pg=PA138.

- ↑ O'Leary, Michael (2010), Revolutions of Geometry, John Wiley & Sons, p. 10, https://books.google.com/books?id=Ch5CrMtyniEC&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Humble, Steve (2016), The Experimenter's A-Z of Mathematics: Math Activities with Computer Support, Taylor & Francis, p. 23, https://books.google.com/books?id=S-80DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23.

- ↑ Geometries and Transformations, 2018, ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5. See Chapter 11: Finite Symmetry Groups, 11.3 Pyramids, Prisms, and Antiprisms.

- ↑ Alexandroff, Paul (2012), An Introduction to the Theory of Groups, Dover Publications, p. 48, ISBN 978-0-486-48813-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=DPrDAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA48.

- ↑ "Convex polyhedra with regular faces", Canadian Journal of Mathematics 18: 169–200, 1966, doi:10.4153/cjm-1966-021-8. See table III, line 1.

- ↑ Uehara, Ryuhei (2020), Introduction to Computational Origami: The World of New Computational Geometry, Springer, p. 62, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-4470-5, ISBN 978-981-15-4470-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=51juDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA62.

- ↑ Kelley (2009), The Humongous Book of Geometry Problems, Penguin Group, p. 455, https://books.google.com/books?id=3XSjAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA455.

- ↑ Wohlleben, Eva (2019), "Duality in Non-Polyhedral Bodies Part I: Polyliner", in Cocchiarella, Luigi, ICGG 2018 - Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Geometry and Graphics: 40th Anniversary - Milan, Italy, August 3-7, 2018, Springer, p. 485–486, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95588-9, ISBN 978-3-319-95588-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=rEpjDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA485

- ↑ Pisanski, Tomaž; Servatius, Brigitte (2013), Configuration from a Graphical Viewpoint, Springer, p. 21, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-8364-1, ISBN 978-0-8176-8363-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=3vnEcMCx0HkC&pg=PA21.

- ↑ Wenninger, Magnus J. (1974), Polyhedron Models, Cambridge University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-521-09859-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=N8lX2T-4njIC&pg=PA50

- ↑ Alexander, Daniel C.; Koeberlin, Geralyn M. (2014), Elementary Geometry for College Students (6th ed.), Cengage Learning, p. 403, ISBN 978-1-285-19569-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=EN_KAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA403.

- ↑ Gillings, R. J. (1964), "The volume of a truncated pyramid in ancient Egyptian papyri", The Mathematics Teacher 57 (8): 552–555.

- ↑ Cajori, Florian (1991), History of Mathematics (5th ed.), American Mathematical Society, p. 87, ISBN 978-1-4704-7059-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=0BZuEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA87.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Mathai, A. M. (1999), An Introduction to Geometrical Probability: Distributional Aspects with Applications, Taylor & Francis, p. 42–43, https://books.google.com/books?id=FV6XncZgfcwC&pg=PA43.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

See also

External links

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.