Biology:Near Eastern fire salamander

| Near Eastern fire salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Salamandra |

| Species: | S. infraimmaculata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Salamandra infraimmaculata Martens, 1885

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Near Eastern fire salamander[2] (Salamandra infraimmaculata), in Arabic arouss al-ayn,[3] is a species of salamander in the family Salamandridae found in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel.[4][5] Its natural habitats are subtropical dry shrubland and forests, often near rivers and freshwater springs. It is threatened by habitat loss.

Description

This species is a black salamander with yellow spots on its back as warning coloration, but none on its belly. It has smooth, shiny skin, usually with four large, yellow blotches on the head. Various subspecies have different patterns of colours, for example, S. i. orientalis is virtually identical to S. i. infraimmaculata, but has a large number of yellow dots all over its body. However, the validity of this subspecies is in question. Another subspecies, S. i. semenovi, has a more rounded head and rose-shaped spots over the top part of the body. It can grow to 324 mm (12.8 in) in length with S. i. infraimmaculata being the largest subspecies. Females are in general larger than males.[5]

Distribution and habitat

In Turkey, Near Eastern fire salamanders can be found in Anatolia. The species is also native to north-western Iran, northern Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, northern Israel near the ancient city of Tel Dan and northern and western Galilee, and the Mount Carmel area. It is found at altitudes of between 180 and 2,000 metres (590 and 6,560 ft).[1][2]

Depending on the terrain, it can be found in various kinds of forests. For example, in Iran, it inhabits open cork forests with scattered trees, while in Turkey and Lebanon, it can be found in damp woods and groves in mountainous and hilly regions, especially near water. It protects itself during the day by hiding under leaves, roots, or rocks and emerges at night to forage. Besides those terrains, it can also be found near springs and the temporary pools that form after winter rains. In Israel, it can be found around pools and spring-fed, slow-moving streams.[1][2]

In spring, to infester their reproductive chances, those animals tend to grow singular yellowish swelling around their eyes: the bigger those heaves are, the better possibilities they have to find a female partner.

Physiology

When these salamanders are larvae, they are able to detect whether the water volume from their pond drops and then they must morph to the next terrestrial phase before the water drops which is developing bigger heads.[6]

Ecology

Salamanders of this species can live up to 23 years for males and 21 years for females. Adults normally live on land, but water is used for breeding. Females lay their eggs in ponds, and both males and females visit the same body of water time after time.[7] The adults are active at night and spend the day in hiding. During the hottest months of summer they may aestivate, depending on location, and individuals at higher elevations hibernate during the winter. They show great fidelity to their hiding and breeding places. It used to be thought that they were resident within small home ranges but it has now been shown that this is not the case. Migrations of populations sometimes take place and individuals sometimes wander far from their normal bases.[8]

Diet

Adults live on land and feed on insects, earthworms, slugs, snails, other small invertebrates, and even young salamanders of other species. The larvae (tadpoles) feed mainly on small crustaceans, mosquito larvae, and tadpoles of frogs and toads. They are very aggressive towards each other and often resort to cannibalism. They are more likely to eat unrelated tadpoles than their litter mates.[9] If fish inhabit the pond, they prey heavily on newt tadpoles, but if not, the salamander tadpoles are at the top of the food chain and have a significant impact on the composition and diversity of species in the pool.[10]

Breeding

Breeding takes place during the cooler months of winter. Although courtship has not been much studied, it is believed to be similar to that of the fire salamander. The male holds the female in a ventral amplexus. He deposits a spermatophore on the ground underneath her and moves his tail and sacrum in such a way that her abdomen comes into contact with it. She grasps it with the lips of her cloaca and draws it inside. A female may receive spermatophores from several different males.[2]

This salamander is ovoviviparous, with the developing embryos being retained in the female's oviduct. There may be about a year between the fertilisation of the eggs and the deposition of live tadpoles into pools. They are not all deposited at one time, and the female visits several ponds, choosing ones without large salamander larvae already present and those with plenty of crevices in which the young tadpoles hide.[11]

Larvae

When born, the larvae weigh about 20 g (0.7 oz) and already have two pairs of legs and two sets of external gills. They use their finned tails for swimming and grow rapidly. They soon encounter others of their kind, and if food is scarce, may become cannibalistic.[9] This may be an adaptive feature related to the decreasing quantity of water in their temporary pools and may be sparked by the presence of dead tadpoles or a change in the quality of the water. Under these circumstances, cannibalism may be an important behaviour that allows some of the tadpoles to survive.[12] Tadpoles grow in size to about 5–7 cm (2.0–2.8 in) before undergoing metamorphosis which takes place after two to four months.[2]

Status

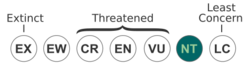

This species is listed as "Near Threatened" in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In some areas, it is quite plentiful, but in others is uncommon or rare. It is considered to be threatened in Israel and Lebanon due to road building and the pollution of water bodies by pesticides. The introduction of predatory fish such as the mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) can severely impact the number of tadpoles that survive to adulthood. In Turkey, the population trend is downwards and the threats include the drying up of water bodies due to the extraction of ground water, the damming of streams, traffic, and the fragmentation of suitable habitat by development.[1] In Israel, it is listed as "Endangered" and is protected by national legislation. In Lebanon, its status is unknown, while in Syria, it is considered to be vulnerable because of habitat destruction.[1][2] In both Turkey and Israel, it is present in some national parks and in these it should receive protection.[1]

Captivity

This salamander can be kept as a pet, and captive breeding has been successful on some occasions. A 26.5-cm female imported from Lebanon in 1966 at a larval stage successfully reproduced 79 larvae in 2007. Four years later, in another gestation period, 102 further larvae were produced.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Theodore Papenfuss; Ahmad Disi; Nasrullah Rastegar-Pouyani; Gad Degani; Ismail Ugurtas; Max Sparreboom; Sergius Kuzmin; Steven Anderson et al. (2009). "Salamandra infraimmaculata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T59466A11927871. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T59466A11927871.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/59466/11927871. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Sparreboom, Max (2014). Salamanders of the Old World. The Salamanders of Europe, Asia, and Northern Africa. Zeist: KNNV Publishing. pp. 320–323. ISBN 978-90-5011-4851.

- ↑ "Arouss al ayn (Salamandra infraimmaculata)". ARKive. http://www.arkive.org/arouss-al-ayn/salamandra-infraimmaculata/.

- ↑ Frost, Darrel R. (2022). "Salamandra infraimmaculata Martens, 1885". Amphibian Species of the World: An Online Reference. Version 6.1. American Museum of Natural History. doi:10.5531/db.vz.0001. https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/Amphibia/Caudata/Salamandridae/Salamandrinae/Salamandra/Salamandra-infraimmaculata.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Salamandra infraimmaculata". Amphibia Web. http://amphibiaweb.org/cgi/amphib_query?where-genus=Salamandra&where-species=infraimmaculata.

- ↑ "The Swiss Army knife of salamanders | The Source | Washington University in St. Louis" (in en-US). 2013-06-26. https://source.wustl.edu/2013/06/the-swiss-army-knife-of-salamanders/.

- ↑ Michael R. Warburg (2007). "Longevity in Salamandra infraimmaculata from Israel with a partial review of life expectancy in urodeles" (PDF). Salamandra 43 (1): 21–34. http://www.salamandra-journal.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=110&Itemid=67.

- ↑ Bar-David, S.; Segev, O.; Hill, N.; Templeton, A. R.; Schultz, C. B.; Blaustein, L. (2007). "Long-distance movements by fire salamanders (Salamandra infraimmaculata) and implications for habitat fragmentation". Israel Journal of Ecology & Evolution 53 (2): 143–159. doi:10.1080/15659801.2007.10639579.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Shai Markman; Naomi Hill; Josephine Todrank; Giora Heth; Leon Blaustein (2012). "Differential aggressiveness between fire salamander (Salamandra infraimmaculata) larvae covaries with their genetic similarity". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 63 (8): 1149–1155. doi:10.1007/s00265-009-0765-y. http://research.haifa.ac.il/~leon/documents/Markman%20et%20al.%20BES%202009.pdf.

- ↑ Blaustein, L.; J. Friedman; T. Fahima (1996). "Larval Salamandra drive temporary pool community dynamics: evidence from an artificial pool experiment". Oikos 76 (2): 392–402. doi:10.2307/3546211.

- ↑ Sadeh, A.; M. Mangel; L. Blaustein (2009). "Context-dependent reproductive habitat selection: the interactive roles of structural complexity and cannibalistic conspecifics". Ecology Letters 12 (11): 1158–1164. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01371.x. PMID 19708967.

- ↑ Sadeh, A.; N. Truskanov; M. Mangel; L. Blaustein (2011). "Compensatory development and costs of plasticity: larval responses to desiccated conspecifics". PLOS ONE 6 (1): e15602. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015602. PMID 21246048.

External links

- Images of Salamandra infraimmaculata on CalPhotos

Further reading

- L. Blank; I. Sinai; S. Bar-David; N. Peleg; O. Segev; A. Sadeh; N. M. Kopelman; A. R. Templeton et al. (December 13, 2012). "Genetic population structure of the endangered fire salamander (Salamandra infraimmaculata) at the southernmost extreme of its distribution". Animal Conservation 16 (4): 412–421. doi:10.1111/acv.12009. ISSN 1469-1795.

Wikidata ☰ Q348747 entry

|