Biology:Nucleoporin

| Nucleoporin 133/155, N terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This domain has a 7-blade beta-propeller structure (PDB 1XKS). | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Nucleoporin_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08801 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR014908 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1XKS / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Nucleoporin 133/155, C terminal (ACE2) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

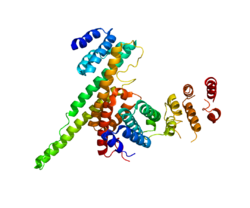

NUP133 (this domain; right) interacting with NUP107 (PDB 3CQC). | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||

| Symbol | Nucleoporin_C | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF03177 | ||||||||||

| InterPro | IPR007187 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| FG repeat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Nucleoporin_FG | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF13634 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0647 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR025574 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Nucleoporins are a family of proteins which are the constituent building blocks of the nuclear pore complex (NPC).[1] The nuclear pore complex is a massive structure embedded in the nuclear envelope at sites where the inner and outer nuclear membranes fuse, forming a gateway that regulates the flow of macromolecules between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Nuclear pores enable the passive and facilitated transport of molecules across the nuclear envelope. Nucleoporins, a family of around 30 proteins, are the main components of the nuclear pore complex in eukaryotic cells. Nucleoporin 62 is the most abundant member of this family.[2] Nucleoporins are able to transport molecules across the nuclear envelope at a very high rate. A single NPC is able to transport 60,000 protein molecules across the nuclear envelope every minute.[3]

Structure

Nucleoporins aggregate to form a nuclear pore complex, an octagonal ring that traverses the nuclear envelope. The ring consists of eight scaffold sub-complexes, with two structural layers of COPII-like coating sandwiching some proteins that line the pore. From the cytoplasm to the nucleoplasm, the three layers of the ring complex is named the cytoplasm, inner pore, and nucleoplasm rings respectively. Different sets of proteins associate on either ring, and some transmembrane proteins anchor the assembly to the lipid bilayer.[4]

In a scaffold subcomplex, both the cytoplasm and the nucleoplasm rings are made up of Y-complexes, a protein complex built out of, among others, NUP133 and NUP107. On each end of each of the eight scaffolds are two Y-complexes, adding up to 32 complexes per pore.[4] The relationship of the membrane curvature of a nuclear pore with Y-complexes can be seen as analogous to the budding formation of a COPII coated vesicle.[3] The proteins lining the inner pore make up the NUP62 complex.[4]

On the nucleoplasm side, extra proteins associated with the ring form "the nuclear basket", a complex capable of tethering the nucleoporin to the nuclear lamina and even to specific parts of the genome.[4] The cytoplasmic end is less elaborate, with eight filaments projecting into the cytoplasm. They don't seem to have a role in nuclear import.[5]

Some nucleoporins contain FG repeats. Named after phenylalanine and glycine, FG repeats are small hydrophobic segments that break up long stretches of hydrophilic amino acids. These flexible parts form unfolded, or disordered segments without a fixed structure.[6] They form a mass of chains which allow smaller molecules to diffuse through, but exclude large hydrophilic macromolecules. These large molecules are only able to cross a nuclear pore if they are accompanied by a signaling molecule that temporarily interacts with a nucleoporin's FG repeat segment. FG nucleoporins also contain a globular portion that serves as an anchor for attachment to the nuclear pore complex.[3]

Membrane nucleoporins associate with both the scaffold and the nuclear membrane. Some of them, like GP210, cross the entire membrane, others (like NUP98) act like nails with structural parts for the lining as well as parts that punch into the membrane.[4] NUP98 was previously thought to be an FG nucleoporin, until it was demonstrated that the "FG" in it have a coiled-coil fold.[4]

Nucleoporins have been shown to form various subcomplexes with one another. The most common of these complexes is the nup62 complex, which is an assembly composed of NUP62, NUP58, NUP54 and NUP45.[7] Another example of such a complex is the Y (NUP107-160) complex, composed of many different nucleoporins. The NUP107-160 complex has been localized to kinetochores and plays a role in mitosis.[8]

Evolution

Many structural nucleoporins contain solenoid protein domains, domains consisting of repeats that can be stacked together as bulk building blocks. There are beta-propeller domain with similarities to WD40 repeats, and more interestingly, unique types of alpha solenoid (bundles of helixes) repeats that form a class of their own, the ancestral coatomer elements (ACE). To date, two classes of ACEs have been identified. ACE1 is a 28-helix domain found in many scaffolding nucleoproteins as well as SEC31, a component of COPII. ACE2, shown in the infobox, is found in yeast Nup157/Nup170 (human Nup155) and Nup133. In either case, the shared domains, like their names suggest, indicate a shared ancestry both within nucleoproteins and between nucleoproteins and cotamers.[9]

All living eukaryotes share many important components of the NPC, indicating that a complete complex is present in their common ancestor.[10]

Function

Nucleoporins mediate transport of macromolecules between the cell nucleus and cytoplasm in eukaryotes. Certain members of the nucleoporin family form the structural scaffolding of the nuclear pore complex. However, nucleoporins primarily function by interacting with transport molecules known as karyopherins.[11] These karyopherins interact with nucleoporins that contain repeating sequences of the amino acids phenylalanine (F) and glycine (G) (FG repeats).[12] In doing so, karyopherins are able to shuttle their cargo across the nuclear envelope. Nucleoporins are only required for the transport of large hydrophilic molecules above 40 kDa, as smaller molecules pass through nuclear pores via passive diffusion. Nucleoporins play an important role in the transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm after transcription.[13] Depending on their function, certain nucleoporins are localized to either the cytosolic or nucleoplasmic side of the nuclear pore complex. Other nucleoporins may be found on both sides. It has been recently shown that FG nucleoporins have specific evolutionary conserved features encoded in their sequences that provide insight into how they regulate the transport of molecules through the nuclear pore complex.[14][15]

Transport mechanism

Nucleoporins regulate the transport of macromolecules through the nuclear envelope via interactions with the transporter molecules karyopherins. Karyopherins will bind to their cargo, and reversibly interact with the FG repeats in nucleoporins. Karyopherins and their cargo are passed between FG repeats until they diffuse down their concentration gradient and through the nuclear pore complex. Karyopherins can serve as an importin (transporting proteins into the nucleus) or an exportin (transporting proteins out of the nucleus).[3] Karyopherins release of their cargo is driven by Ran, a G protein. Ran is small enough that it can diffuse through nuclear pores down its concentration gradient without interacting with nucleoporins. Ran will bind to either GTP or GDP and has the ability to change a karyopherin's affinity for its cargo. Inside the nucleus, RanGTP causes an importin karyopherin to change conformation, allowing its cargo to be released. RanGTP can also bind to exportin karyopherins and pass through the nuclear pore. Once it has reached the cytosol, RanGTP can be hydrolyzed to RanGDP, allowing the exportin's cargo to be released.[16]

Pathology

Several diseases have been linked to pathologies of nucleoporins, notably diabetes, primary biliary cirrhosis, Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Overexpression of the genes that encode for different nucleoporins also have been shown to be related to the formation of cancerous tumors.

Nucleoporins have been shown to be highly sensitive to glucose concentration changes. Therefore, individuals affected by diabetes often exhibit increased glycosylation of nucleoporins, particularly nucleoporin 62.[2]

Autoimmune conditions such as anti-p62 antibodies, which inhibit p62 complexes have links to primary biliary cirrhosis which destroys the bile ducts of the liver.[7]

Decreases in the production of the p62 complex are common to many neurodegenerative diseases. Modification of the p62 promoter by oxidation is correlated with Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and Parkinson's disease among other neurodegenerative disorders.[17]

Increased expression of the NUP88 gene, which encodes for nucleoporin 88, is commonly found in precancerous dysplasias and malignant neoplasms.[18]

Nucleoporin protein aladin is a component of the nuclear pore complex. Mutations in the aladin gene are responsible for triple-A syndrome, an autosomal recessive neuroendocrinological disease. Mutant aladin causes selective failure of nuclear protein import and hypersensitivity to oxidative stress.[19] The import of DNA repair proteins aprataxin and DNA ligase I is selectively decreased, and this may increase the vulnerability of the cell's DNA to oxidative stress induced damages that trigger cell death.[19]

Examples

Each individual nucleoporin is named according to its molecular weight (in kilodaltons). Below are several examples of proteins in the nucleoporin family:

- NUP35, NUP37, NUP43, NUP50

- NUP54, NUP62, NUP85, NUP88, NUP93, NUP98

- NUP107, NUP133, NUP153, NUP155, NUP160, NUP188

- NUP205, NUP210, NUP214

References

- ↑ "From nucleoporins to nuclear pore complexes". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 9 (3): 401–11. June 1997. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(97)80014-2. PMID 9159086.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Responsiveness of the state of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of nuclear pore protein p62 to the extracellular glucose concentration". The Biochemical Journal 350 Pt 1 (Pt 1): 109–14. August 2000. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3500109. PMID 10926833.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Lodish H (2013). Molecular Cell Biology (Seventh ed.). New York: Worth Publ.. ISBN 978-1-4292-3413-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Beck, Martin; Hurt, Ed (21 December 2016). "The nuclear pore complex: understanding its function through structural insight". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 18 (2): 73–89. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.147. PMID 27999437. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311776942. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ Walther, TC; Pickersgill, HS; Cordes, VC; Goldberg, MW; Allen, TD; Mattaj, IW; Fornerod, M (8 July 2002). "The cytoplasmic filaments of the nuclear pore complex are dispensable for selective nuclear protein import.". The Journal of Cell Biology 158 (1): 63–77. doi:10.1083/jcb.200202088. PMID 12105182.

- ↑ "Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: The FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 (5): 2450–5. 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0437902100. PMID 12604785. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.2450D.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Profile and clinical significance of anti-nuclear envelope antibodies found in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: a multicenter study". Journal of Autoimmunity 20 (3): 247–54. May 2003. doi:10.1016/S0896-8411(03)00033-7. PMID 12753810.

- ↑ "The entire Nup107-160 complex, including three new members, is targeted as one entity to kinetochores in mitosis". Molecular Biology of the Cell 15 (7): 3333–44. July 2004. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0878. PMID 15146057.

- ↑ Whittle, JR; Schwartz, TU (9 October 2009). "Architectural nucleoporins Nup157/170 and Nup133 are structurally related and descend from a second ancestral element.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (41): 28442–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.023580. PMID 19674973.

- ↑ Neumann, N; Lundin, D; Poole, AM (8 October 2010). "Comparative genomic evidence for a complete nuclear pore complex in the last eukaryotic common ancestor.". PLOS ONE 5 (10): e13241. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013241. PMID 20949036. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...513241N.

- ↑ "Deciphering networks of protein interactions at the nuclear pore complex". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 1 (12): 930–46. December 2002. doi:10.1074/mcp.t200012-mcp200. PMID 12543930.

- ↑ "Introduction to Nucleocytoplasmic Transport". Xenopus Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. 322. 2006. pp. 235–58. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-000-3_17. ISBN 978-1-58829-362-6.

- ↑ "Molecular basis for specificity of nuclear import and prediction of nuclear localization". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1813 (9): 1562–77. September 2011. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.013. PMID 20977914.

- ↑ "Evolutionarily Conserved Sequence Features Regulate the Formation of the FG Network at the Center of the Nuclear Pore Complex". Scientific Reports 5: 15795. November 2015. doi:10.1038/srep15795. PMID 26541386. Bibcode: 2015NatSR...515795P.

- ↑ "Physical motif clustering within intrinsically disordered nucleoporin sequences reveals universal functional features". PLOS ONE 8 (9): e73831. 2013-09-16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073831. PMID 24066078. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...873831A.

- ↑ "Ran, a GTPase involved in nuclear processes: its regulators and effectors". Journal of Cell Science 109 ( Pt 10) (10): 2423–7. October 1996. doi:10.1242/jcs.109.10.2423. PMID 8923203.

- ↑ "Oxidative damage to the promoter region of SQSTM1/p62 is common to neurodegenerative disease". Neurobiology of Disease 35 (2): 302–10. August 2009. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.015. PMID 19481605.

- ↑ "Entrez Gene: NUP88 nucleoporin 88kDa"

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "ALADINI482S causes selective failure of nuclear protein import and hypersensitivity to oxidative stress in triple A syndrome". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (7): 2298–303. February 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505598103. PMID 16467144. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.2298H.

External links

- Nucleoporin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Nucleoporin (InterPro search)

|