Biology:Ornamental bulbous plant

Ornamental bulbous plants, often called ornamental bulbs or just bulbs in gardening and horticulture, are herbaceous perennials grown for ornamental purposes, which have underground or near ground storage organs. Botanists distinguish between true bulbs, corms, rhizomes, tubers and tuberous roots, any of which may be termed "bulbs" in horticulture. Bulb species usually lose their upper parts during adverse conditions such as summer drought and heat or winter cold. The bulb's storage organs contain moisture and nutrients that are used to survive these adverse conditions in a dormant state. When conditions become favourable the reserves sustain a new growth cycle. In addition, bulbs permit vegetative or asexual multiplication in these species.[1][2] Ornamental bulbs are used in parks and gardens and as cut flowers.[2]

Terminology

The word "bulb" has a somewhat different meaning to botanists than it does to gardeners and horticulturalists. In gardening, a "bulb" is a plant's underground or ground-level storage organ that can be dried, stored and sold in this state, and then planted to grow again. Many bulbs in this sense are produced by geophytes – plants whose growing point is below ground level. However, not all bulbs in the gardening sense are produced by geophytes. For example, rhizomatous irises are included in books on ornamental bulbs, but their growing points are above ground. Many bulbs are produced by lilioid monocots, but not all lilioid monocots have bulbs. Brian Mathew says that "we just have to accept that there is no accurate term which we can use for this group of plants and we are left with 'bulbs' as the snappiest and most convenient."[3]

Botanically, gardeners' "bulbs" may be true bulbs, corms, rhizomes or tubers,[1][2] or combinations of these.

Types

True bulbs

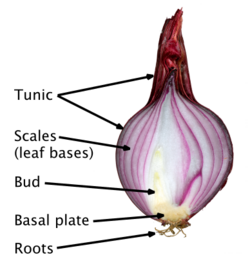

A true bulb (i.e. a bulb in the botanical sense) is an underground vertical shoot that has modified leaves (or thickened leaf bases) that are used as food storage organs by the plant. The bottom of the bulb is made up of a short section of stem forming the basal plate. Storage leaves are produced from the top of the basal plate, roots from the underside.[4] Genera with true bulbs are Muscari, Allium, Tulipa and Narcissus.[5]

Corms

A corm is a short, vertical, swollen underground plant stem consisting of one or more internodes with at least one growing point, with protective leaves modified into skins or tunics. The thin tunic leaves are dry papery, dead sheaths, formed from the leaves produced the year before. They act as a covering that protects the corm from insects and water loss. Internally a corm is mostly made of starch-containing parenchyma cells above a more-or-less circular basal node that grows roots. Corms are sometimes confused with true bulbs; they are often similar in appearance to bulbs externally, but corms are internally structured with solid tissues, which distinguishes them from bulbs, which are mostly made up of layered fleshy scales.[4]

Rhizomes

A rhizome is a horizontal stem that often grows underground, usually sending out roots and shoots from its nodes. Some plants have rhizomes that grow above ground or that lie at the soil surface, including some Iris species. Usually, rhizomes have short internodes; they send out roots from the bottom of the nodes and new upward-growing shoots from the top of the nodes. Examples of plants that grow in this way include irises, lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis) and cannas.[4]

Tubers

A stem tuber may form from thickened rhizomes or stolons. The tops or sides of the tuber produce shoots that grow into typical stems and leaves, and the undersides produce roots. Such tubers tend to form at the sides of the parent plant and are most often located near the soil surface. A below ground stem tuber is normally a short-lived storage and regenerative organ developing from a shoot that branches off a mature plant. The new tubers are attached to a parent tuber or form at the end of an underground rhizome. In the autumn the plant dies except for the new offspring stem tubers, which in spring regrow one or more new shoots producing stems and leaves. Some plants also form smaller tubers and/or tubercules, which act like seeds, producing small plants that resemble (in morphology and size) seedlings. Some stem tubers, such as those of tuberous begonias, are long lived, but many tuberous plants have tubers that survive only until the plants are in full leaf, at which point the tuber is reduced to a shrivelled up husk.[4]

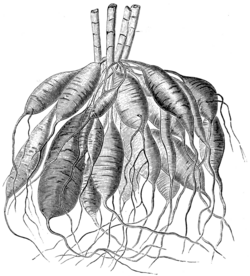

Roots can also form tuberous structures (tuberous roots) that are in some ways similar to stem tubers, but of a different anatomical origin. Ornamental plants with tuberous roots include the Persian buttercup, Ranunculus asiaticus,[6] and dahlias.[7] When sold in the dry form, dahlia "bulbs" consist of a cluster of tuberous roots attached to one or more stems. Only the stems produce buds, from around the "collar" close to where the roots are attached. A tuber without any attached stem will not grow.[8]

Tubers may form from the hypocotyl of the young seedling, as in Cyclamen.[9] Since the hypocotyl is a region between the stem and the roots, such tubers are variable in their anatomy and growth habits. Thus the roots of Cyclamen graecum grow from the base of the tuber, suggesting it is a stem tuber, whereas those of Cyclamen hederifolium mostly grow from the upper surface of the tuber, suggesting it is a root tuber.[10]

Environmental adaptations and distribution

Annual species complete their life cycle during favourable seasons and pass unfavourable ones as seeds. Bulbous plants, on the other hand, have developed storage organs as a reserve to allow them to survive unfavourable conditions in a resting condition in order to begin growth again when environmental conditions become more favourable.[1] The dormant or resting period may be in summer or winter, or may depend on rainfall, as in the tropics.[11] The different strategies enable bulbous plants to survive adverse conditions such as extremely hot and dry summers, very cold winters, or periods of drought.[citation needed]

Summer dormancy

Most bulbous plants are adapted to hot, dry summers and cooler, wetter winters. They are dormant through the summer and grow during the autumn, winter and spring.[12] Within this group, there are variations, largely determined by how cold the winter is. Many tulips (Tulipa species) of Asian origins, for example, have adapted to an extreme continental climate, with dry, very hot summers, very cold winters and springs with short showers. They grow mainly during the spring.[1] In cultivation such tulips may be planted in late autumn (e.g. November in the northern hemisphere).[13] In regions where winters are milder, some species, such as Crocus cartwrightianus, flower in the autumn, either at the same time as the leaves appear or before.[14] Others, such as Arum creticum, produce leaves in the autumn which last through the winter until the plant flowers in the spring.[15]

Summer drought occurs particularly, but not exclusively, in those regions of the world with a Mediterranean climate, which are rich in bulbous plants. Such regions include the Mediterranean itself through to Central Asia, the south west of South Africa , the south west of Australia , parts of the western United States, such as California , and parts of western South America, particularly Chile .[11]

Many species that grow in the understory of deciduous woods or forests are also summer dormant. They use their stored reserves in order to grow rapidly and complete their annual growth-cycle at the beginning of spring before the developing tree canopy blocks out the sun's light.[1] North America is home to many such woodland bulbs, including Erythronium, Trillium and some lilies, such as Lilium pardalinum.[16] The common bluebell, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, is native to western parts of Europe, but particularly the British Isles,[17] where it carpets the floor of some woods. The woodlands of Asia, including China and Japan , are home to bulbous plants such as arisaemas and the giant cardiocrinums.[16]

Some bulbous plants grow in communities that are adapted to recurrent fires during the dry season (for example, many Iridaceae species). During these periods the plants are dormant and in this way can survive the heat of the fire. The fires clean the surface vegetation, eliminating competition and also supplying nutrients to the ground from the ashes of the burnt plants. When the first rains fall, the bulbs, corms and rhizomes rapidly start to shoot, starting a new period of growth and development sustained by the reserves accumulated in their storage tissues during the previous season. Various South African species from the genus Cyrtanthus, for example, are well known for their ability to flower rapidly after natural grassland wildfires, and for this reason several of these species are known as "fire lilies". In fact, some species, such as Cyrtanthus contractus, only flower after a wildfire.[18]

Winter dormancy

A second category of bulbous plants are those adapted to dry, generally cool winters and warmer, wetter summers. They are dormant through the winter and grow in spring, summer and autumn. Regions of South Africa and Lesotho with this type of climate include the East Cape, and the Drakensberg mountains in the north east of Western Cape province, which are particularly rich in bulbous species,[19] including plants such as gladioli, Eucomis and Rhodohypoxis. Other areas with similar winter drought include parts of Central America, such as Mexico where the tiger flower (Tigridia pavonia) is found.[20]

Seasonal dormancy

In some areas of the tropics, rainfall is interspersed with periods of dryness; more than one wet/dry cycle may occur in a year. Bulbous plants in these areas are adapted to warm, wet periods followed by warm, dry periods. They typically flower near the beginning of the rainy season. Such a climate occurs in Kenya, which has wet conditions in October to December and then again in February to May. Glory-lilies (Gloriosa) and Crinum species are examples of bulbous plants adapted to these conditions. Tropical Asia has similarly adapted bulbous plants, such as species of Hedychium (gingers).[21]

History of use

Plants with fleshy underground parts were probably first used as food. Onions (Allium cepa) were cultivated in Ancient Egypt. In South America, the potato (Solanum tuberosum), oca (Oxalis tuberosa) and the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) were cultivated for thousands of years.[1] Other parts of bulbous plants were also used in cooking. The Minoans of Crete grew and traded saffron (either the wild species Crocus cartwrightianus or the cultivated Crocus sativus). The plant is depicted in paintings from around 1550 BC.[22] Saffron consists of the dried stigmas of the flowers, and is used as a spice and also as a dye.[14] Some bulbous plants were used in medicine in classical times; one example is the sea squill (Drimia maritima) which grows from a true bulb.[22]

Wall paintings dated to around 1700–1600 BC from Minoan Akrotiri provide some of the earliest evidence for the apparently ornamental use of bulbous plants. Some of the plants in the frescos are clearly lilies, which have usually been identified as Lilium candidum. However, this species has white flowers, and those in the frescos are red, which suggests they may be Lilium chalcedonicum.[23] L. candidum, the Madonna lily, was later used as a symbol in Christianity, where the Virgin Mary was represented with lilies in her hands.[24] The symbol of the Fleur de Lys was originally based on the flower of a species of Iris (Iris pseudacorus) that appeared in Egyptian and Indian religious paintings long before it was adopted as the emblem of the kings of France in the 5th Century.[citation needed]

Many ornamental bulbs were introduced into Europe via Turkey and the Ottoman Empire. Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (who reigned 1520–1566) was noted for his love of gardens, where tulips and other bulbs were grown. Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, the ambassador to the sultan from Emperor Ferdinand I in Vienna, observed ornamental bulbous plants such as narcissi, hyacinths and "those which the Turks call tulipam".[22] The botanist Carolus Clusius, who was based in Vienna from 1573 to around 1580, devoted one volume of his 1576 botanical work Rariorum Plantarum Historia to bulbs, some of which he knew from introductions via Turkey, such as tulips, Iris susiana, Galanthus elwesii and Fritillaria persica. Clusius had a major impact on bulb growing in Europe. Through his later position as the Director of the Leiden Botanic Garden, he established the Netherlands as the centre of commercial ornamental bulb growing.[25]

It is therefore apparent that bulbous plants have served as food and symbols of religion and royal power for thousands of years. They have also been admired and used for the beauty of their flowers since time immemorial and by many civilizations. The list of the countries that have used bulbous plants as ornaments since the Christian era is long and includes Greece, Egypt, China , Korea and India among others. The list of genera cultivated in these countries as ornamental plants is even longer: Lycoris, Lilium, Crocus, Cyclamen, Narcissus, Scilla, Gladiolus, Muscari, Ranunculus, Allium, Iris and Hyacinthus.[1][2]

Bulbous plants in the garden

Some varieties of bulbous plants thrive under adverse conditions such as poor soil or shade, and are therefore well suited to use in a garden. Varieties can be chosen that bloom at various times of year. They can be intermingled with other plants, used in pots, or even placed in the lawn or underneath fruit trees.[2][1]

Regarding their size, it is possible to find species that only grow a few centimetres such as Crocus minimus up to examples of 3.6m such as Cardiocrinum giganteum.[1][26]

While some bulbs are poisonous or at least inedible to humans,[example needed] many bulbs – especially those of the onion family (leeks, garlic, chives, shallots) – are grown both privately and commercially as food crops. The onion especially provides the basis for a huge variety of dishes.[citation needed]

Flowerbeds and borders

Bulb species are traditionally planted in flowerbeds (parterres) and herbaceous borders in parks and gardens. The selection of species to plant depends on various factors, such as the soil type, the position (sunny or shady location), the colour or effect that is required and the season of the year when the plants are required to flower.

Some examples of bulbous plant genera and their flowering season are given below:

- Spring flowering bulbs.[27][28] Spring is the most typical season for bulbs to flower. Some examples are: Allium, Arum, Asphodelus, Camassia, Convallaria, Crocus, Cyclamen, Eranthis, Freesia, Fritillaria, Galanthus, Hyacinthus, Hippeastrum, Iris, Ixia, Leucojum, Muscari, Narcissus, Ornithogalum, Ranunculus, Scilla, Trillium and Tulipa[29] and Zephyranthes.

- Summer flowering bulbs:[30][31] Achimenes, Agapanthus, Allium, Alstroemeria, Amaryllis, Anemone, Begonia, Calochortus, Canna, Crinum, Crocosmia, Dahlia, Dierama, Eucomis, Galtonia, Gladiolus, Gloriosa, Haemanthus, Hymenocallis, Lilium,[32] Oxalis, Pancratium, Paradisea, Polianthes, Sprekelia, Tritonia, Watsonia, Zantedeschia.

- Autumn (fall) flowering bulbs:[33] Crocus, Colchicum, Cyclamen, Nerine, Sternbergia.

- Winter flowering bulbs: some species from the following genera: Galanthus, Crocus, Cyclamen and Eranthis.

Some species of bulbous plants grow naturally in shady or woodland areas, and thus are well suited to areas in a garden that have similar conditions. Some species for shade are Allium ursinum, Anemone blanda, Anemone nemorosa, Arum italicum, Convallaria majalis, Corydalis flexuosa, Cyclamen purpurascens, Disporum flavescens, Erythronium, Fritillaria pallidiflora, Galanthus, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, Iris douglasiana, Leucojum vernum, Lilium martagon, Ranunculus ficaria, Sanguinaria canadensis, Smilacina racemosa, Trillium and Uvularia grandiflora.

Naturalization

In large parks it is possible to plant some species so that they multiply spontaneously and grow amongst the grass or under trees. This practice, the naturalization of a species, is widely used in northern Europe and requires that the species' ecological requirements be satisfied. The most obvious advantage of this cultivation method is that it minimizes the attention the plants require once they have been naturalized. The plants that are suitable for naturalization are those that are sufficiently small but able to compete with the surrounding grass, they must be robust and able to withstand year after year of inclement weather and they must be prolific in order to spread rapidly.[34][35]

Some of the bulbs that are suitable for naturalization in parks include: Allium, Anemone, Arum, Colchicum, Crocus, Cyclamen, Endymion, Fritillaria, Galanthus, Ipheion, Leucojum, Lilium, Muscari, Narcissus, Ornithogalum, Scilla, Sternbergia and Tulipa.

Rock gardens

A rock garden is a garden that uses a combination of rocks and small plants. The plants are often chosen for their suitability to rocky terrain. Some of the bulb genera that are most suitable for rock gardens include:[1] Allium, Anemone, Anthericum, Bulbocodium, Chionodoxa, Cyclamen, Eranthis, Erythronium, Galanthus, Ipheion, Muscari, Ornithogalum, Oxalis, Romulea, Rhodohypoxis and Scilla.[citation needed]

Multiplication

Bulbs can reproduce sexually, through seeds, or even vegetatively. Reproduction through seeds is generally used to rapidly increase the number of individuals of a given species and to improve genetic diversity. Many of the bulb species are self-incompatible, so pollination can only occur between clones of different plants in order to obtain seeds. The majority of seeds from bulbous plants germinate well if they are sown as soon as they reach maturity. Some species need a cold period in order to germinate. The biggest problem in reproducing through seeds is that the resulting plants have a greater variability in a wide range of characteristics, such as flower colour and height and flowering period. This means that asexual or vegetative reproduction is normally used commercially to propagate this type of plant. This means that the characteristics of a determined cultivar remain unaltered.[36]

Bulbs can reproduce vegetatively in a number of ways depending on the type of storage organ the plant has.[36][37][38][39]

Commercial production

Bulbs can be evergreen, such as Clivia, Agapanthus and some species and varieties of Iris and Hemerocallis. However, the majority are deciduous, dying down to the storage organ for part of the year. This characteristic has been taken advantage of in the commercialization of these plants. At the beginning of the rest period the bulbs can be dug out of the ground and prepared for sale as if they remain dry they do not need any nutrition for weeks or months.[1][2]

Bulbous plants are produced on an industrial scale for two main markets, cut flowers and dried bulbs. The bulbs are produced to satisfy the demand for bulbs for parks, gardens and as house plants, in addition to providing the bulbs necessary for the production of cut flowers. The international trade in cut flowers has a worldwide value of approximately 11,000 million Euros, which gives an idea of the economic importance of this activity.

The Netherlands has been the leader in commercial production since the start of the 16th Century, both for the dried bulb market and for cut flowers. In fact, with approximately 30,000 hectares dedicated to this activity the production of bulbs in the Netherlands represents 65% of global production. The Netherlands also produces 95% of the international market in bulbs dedicated to the production of cut flowers. The United States is the second largest producer followed by France , Japan , Italy, United Kingdom , Israel, Brazil and Spain .[40]

International societies dedicated to bulbous plants

- Established in 1933, this society is an international educational and scientific organization, it is a charity dedicated to the dissemination of information regarding the cultivation, conservation and botany of all types of bulbous plants. Their website contains an excellent gallery of high quality photographs of bulbous plants.

- Organized in 2002, this society disseminates information and shares experiences regarding the cultivation of ornamental bulbous plants. Their website contains an exceptional educational resource, "Pacific Bulb Society Wiki", with images and information regarding numerous species of bulbous plants.

- Australian Bulb Association. https://web.archive.org/web/20090518011847/http://www.ausbulbs.org/index.htm

- Organized in 2001 it possessed an excellent collection of photographs of bulbous plants on its website.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Rossi 1990.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Hessayon 1999.

- ↑ Mathew 1997, p. 1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Stern, Kingsley R. (2006). Introductory Plant Biology, 10th ed.. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-111666-4.

- ↑ Schauenberg 1965, p. 2.

- ↑ Mathew 1997, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Mathew 1997, p. 84.

- ↑ Schauenberg, Paul (1965). The Bulb Book. London: Frederick Warne. OCLC 3012223. p. 146.

- ↑ Grey-Wilson, Christopher (1988). The Genus Cyclamen. Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-111-3. pp. 17–18, 58.

- ↑ Rix 1983, p. 12.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Mathew 1997, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Rix 1983, p. 43.

- ↑ Schauenberg 1965, p. 267.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mathew 1987, p. 56.

- ↑ Mathew 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Rix 1983, pp. 128–130.

- ↑ Fred Rumsey. "Hyacinthoides non-scripta (British bluebell) > Distribution and ecology". Species of the day. Natural History Museum. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/species-of-the-day/biodiversity/endangered-species/hyacinthoides-non-scripta/distribution-ecology/index.html.

- ↑ Duncan, G.. "Cyrtanthus". National Botanical Garden in Kirstenbosch, South Africa. http://www.plantzafrica.com/plantcd/cyrtanthus.htm.

- ↑ Phillips & Rix 1989.

- ↑ Mathew 1997, p. 11–12.

- ↑ Rix 1983, pp. 89–92.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Rix 1983, p. 93.

- ↑ Nugent, Marcia (2008). "Seasonal Flux—Three Flowers for Three Seasons: Seasonal Ritual at Akrotiri, Thera". Iris 21: 2–20. http://classics-archaeology.unimelb.edu.au/CAV/iris/volume21/nugent.pdf. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ↑ Schauenberg 1965, p. 204.

- ↑ Rix 1983, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Taylor 1996.

- ↑ "International bulb center spring blooming bulbs". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/spring-blooming-bulbs.

- ↑ "Spring Flowering Bulbs Picture Book". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/photos/Spring-flowering-Picture-Book.xml.

- ↑ "Tulip Picture Book". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/photos/Tulip-book.xml.

- ↑ "International bulb center summer blooming bulbs". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/summer-blooming-bulbs.

- ↑ "Summer Flowering Bulbs Picture Book". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/photos/Summer-flowering-bulbs-Picture-Book.xml.

- ↑ "Lily Picture Book". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/photos/Lily-book.xml.

- ↑ "International bulb center autumn blooming bulbs". http://www.bulbsonline.org/ibc-jsp/en/education/beroepsonderwijs/autumn-blooming-bulbs.

- ↑ "Landscaping brochure, International bulb centre". http://video.bulbsonline.org/emag/HOVUK/flash.html.

- ↑ "Flower Bulb Research Program". https://flowerbulbs.cornell.edu/.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Skelmersdale, L. (1978). "Propagation of bulbous and bulbous-like plants.". Proc. Inter. Plant Prop. Soc. 28: 209–215.

- ↑ Hartmann, H.; Kester, D. (1987) (in es). Propagación de plantas, principios y prácticas. México: Compañía Editorial Continental. ISBN 968-26-0789-2.

- ↑ "Multiplicacion de plantas bulbosas" (in es). Infojardin. http://articulos.infojardin.com/bulbosas/multiplicacion-bulbosas.htm.

- ↑ Keener, E. (2004). "Propagating bulbous plants". http://ucce.ucdavis.edu/files/filelibrary/616/13733.doc.

- ↑ Claps, L. (2001) (in es). Perfil del mercado internacional de bulbos para flor. INTA, UEM Santa Cruz.

Bibliography

- Hessayon, D.G. (1999). The Bulb Expert. London: Transworld Publishers.

- Mathew, Brian (1978). The Larger Bulbs. London: B.T. Batsford (in association with the Royal Horticultural Society). ISBN 978-0-7134-1246-8.

- Mathew, Brian (1987). The Smaller Bulbs. London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-4922-8.

- Mathew, Brian (1997). Growing Bulbs : The Complete Practical Guide. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-4920-4.

- Phillips, R.; Rix, M. (1989). Bulbs. Pan Books.

- Rix, Martyn (1983). Growing Bulbs. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-917304-87-3.

- Rossi, Rosella (1990) (in es). Guía de Bulbos. Barcelona: Grijalbo.

- Taylor, P. (1996). Gardening with Bulbs. London: Pavilion Books.

External links

- International bulb centre

- Flower Bulb Research Program, Dept. of Horticulture, Cornell University

- New York Botanical Garden: "Bulb Care and Selection"

- RHS bulbs

|