Biology:Thalassotitan

| Thalassotitan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Syntype skull and jaws (MNHM.KH.231) of T. atrox from Ouled Abdoun Basin, Morocco | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Superfamily: | †Mosasauroidea |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Tribe: | †Prognathodontini |

| Genus: | †Thalassotitan Longrich et al., 2022 |

| Type species | |

| †Thalassotitan atrox Longrich et al., 2022

| |

Thalassotitan ("titan of the seas") is an extinct genus of large mosasaurs (a group of extinct marine lizards) that lived during the late Maastrichtian of the Cretaceous period in what is now Morocco, around 66 million years ago. The only known species is T. atrox, described in 2022 from fossils discovered in the Ouled Abdoun Basin, where many other mosasaurs have been found. It was assigned to the tribe Prognathodontini alongside other mosasaurs like Prognathodon and Gnathomortis. The prognathodontines are separated from other mosasaurs based on their massive jaws and robust teeth.

This genus shows definitely that mosasaurs evolved to take over the apex predator niche in the oceans of the Late Cretaceous which is now filled by sharks and orcas. Heavy wear on its teeth and fossils found in the vicinity of the holotype etched by acid wear from partial digestion suggest that this mosasaur had a diet consisting of smaller mosasaur species, plesiosaurs, large predatory fish, and sea turtles.

Etymology

The genus name Thalassotitan is a portmanteau of the Ancient Greek θάλασσα (thálassa, "sea") and τιτάν (tītā́n, "giant"), referring to the mosasaur's large size. The specific epithet atrox is a Latin word translating to "cruel" or "merciless", which references the species' trophic position as an apex predator and frequency of intraspecific bite marks on fossils.[1]

Description

Thalassotitan was one of the largest mosasaurs. Its skull measured up to 1.3 meters (4.3 ft) in length, corresponding to a total length of 9–10 meters (30–33 ft).[1]

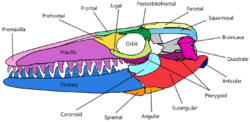

Skull

Like all prognathodontines, the skull of Thalassotitan is blunt and robust. The premaxilla, the bone bearing the tip of the skull, is very short in a lateral view but broad and convex when viewed dorsally. The body of the premaxilla contains numerous pits called neurovascular foramina, which are believed to house tactile nerves that are very sensitive to touch. The internarial bar, a long extension of the premaxilla reaching up to the frontal bone, is broad as it passes between the maxilla (the main tooth-bearing upper jaw bone) and external nares (the openings that house the nostrils) but narrows into a slender rod as it contacts with the frontal. Between the maxilla, the internarial bar forms a distinct low and short keel. The maxilla is short, robust, and deep. Its surface is flat except for a low and broad ridge lining just above the teeth.

Neurovascular foramina line this margin, increasing in size as they progress towards the back of the skull. The texture of the maxilla's surface is rough, which is especially apparent in larger individual, caused by a network of veined grooves to house blood vessels. The external nares extend from and to above the fourth and twelfth maxillary teeth. The jugal bone, which is located just below the eye, is broad and robust. The frontal bone is short and broad, shaped almost like an isosceles triangle, with large neurovascular foramina at the center. The pineal foramen, which contains the parietal eye, is small and long. The supratemporal fenestrae, large openings between the eyes and the back end of the skull, take up nearly a quarter of the entire skull length and are somewhat triangular. The dentary, the tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw, is short, wide, robust, and curved concave towards the upper jaws. Many bones of the upper jaw are tightly sutured together; its two tooth-bearing bones the premaxilla and maxilla were connected through interlocking joints containing an unusual series of flanges and grooves while an interdigitating set of tongue-and-groove joints secure the maxilla and prefrontal bone.[1]

Teeth

Thalassotitan teeth are roughly conical in shape, lightly curved, large in size, and robust in build. They are most similar to the teeth of P. saturator except in being slightly shorter and stockier. Tooth crowns are slightly swollen around its base next to the root, but they do not form a round circumference. The surfaces of the crown are generally smooth but may sometimes have faint ridges depending on individual or ontogenetic variation. The enamel at the tip contain veinous ridges and coarse bumps. Cutting edges are well-developed and finely serrated. Each tooth has two cutting edges, but their positions differ depending on the tooth's position in the jaw. Towards the front of the jaw, the front-facing cutting edges are more pronounced than the diminished back-facing edges. In the middle and near the end of the jaw, both edges are of equal development and located diametrically opposite to each other. At the end of the jaw, the back-facing edges become more pronounced. The tooth roots are massive and barrel-shaped. Deep pits occur within the roots, from which new replacement teeth are formed.[1]

Like all mosasaurs, Thalassotitan had four types of teeth, corresponding to the jaw bones they are located on. On the upper jaw were the premaxillary teeth, maxillary teeth, and pterygoid teeth (located separate from the main jawline near the rear of the skull); while on the lower jaw only the dentary teeth were present. Thalassotitan had in each jaw row from front to back: two premaxillary teeth, twelve maxillary teeth, at least six pterygoid teeth (the pterygoids were not fully preserved), and fourteen dentary teeth. The dentary teeth are generally flatter by the side than the maxillary teeth. Heterodonty is present, meaning that tooth shape changes down the jawline. The first four or five teeth are tall, narrow, and slightly curved, which become stockier, erect, and more robust around the middle of the jawline, then become shorter (as broad as they are tall), hooked, and flatter by the side. The pterygoid teeth are strongly hooked but are also large and robust, nearly approaching the size of the teeth on the main jawlines.[1]

Postcranial skeleton

The postcranial skeleton is not fully known, only fossils representing a little more than the front half of the body have been found.[1]

The general shape of the vertebrae are typical for mosasaurines. They are procoelous, meaning that the front side is deeply cupped concavely and the back side is bulged convexly. The cervical (neck) vertebrae are slightly wider than long. Its atlas holds rectangular or triangular neural arches; another single tall neural arch is also present at the top of the vertebra. The articular surfaces, which atach to the cartilage that connect vertebrae together, is initially heart-shaped but becomes rounded at the rearmost cervicals. The dorsal (back) vertebrae are slightly longer than wide with tall neural arches, rounded articular surfaces, and large rectangular transverse processes. The ribs are short and robust.[1]

The pectoral girdle is robust and most similar with that in P. overtoni and Mosasaurus conodon, albeit more square-shaped than the latter. The two bones making up the girdle, the scapula and coracoid, are similar in sizes. They loosely contact with each other, but their contact point is nevertheless wider than the glenoid fossa. The scapula is shaped like a square, being as long as it is wide. It lacks a defined scapular neck but expands from front to back, forming a fan-like convex blade. The coracoid is also somewhat squarish and lacks a well-defined neck. Its margins are weakly concave in the front and back but very convex at the bottom.[1]

The forelimbs formed long paddles that resembled mosasaurin mosasaurs like Mosasaurus and Plotosaurus but more primitive in possessing longer but fewer phalanges. The humerus is very stocky and resemble that in P. overtoni except in the expansion of the glenoid condyle beyond the postglenoid process. The radius is unusually shaped for a mosasaur. It is as large as the humerus and much larger than the ulna and takes on a crescent-like or subrectangular form, unlike smaller hourglass-shaped radii in typical mosasaurs.[1]

Classification

Thalassotitan is a member of the Prognathodontini tribe of the Mosasaurinae subfamily, with other members including Prognathodon and Gnathomortis. Morphologically, it is most similar to the giant mosasaurs P. currii and P. saturator, and a phylogenetic analysis by Longrich et al. (2022) recovered Thalassotitan in a clade between the two. This creates an unnatural paraphyletic relationship that reflects a wider issue with the genus Prognathodon as a whole. Several studies over the past decade found that Prognathodon is in general not monophyletic and in need of revision. Longrich et al. (2022) suggested such a revision may include an expansion of the Thalassotitan genus to include P. currii and P. saturator.[1] However, due to a high degree of convergent evolution in the relationship-determining traits among many mosasaurs (especially among prognathodontines), phylogenetic results between each study are seldom consistent, mystifying exactly which species must be revised to stabilize the Prognathodontini. For example, some studies recovered P. currii and P. saturator as phylogenetically unrelated species with either falling outside a monophyletic Prognathodon, while other studies yield variable placements for the type species P. solvayi as either outside a monophyletic P. currii-P. saturator clade in support of Longrich et al. (2022) or within it, which would in theory invalidate Thalassotitan as a junior synonym under the principle of priority.[1]

The following cladogram is modified from Longrich et al. (2022).[1]

| Mosasaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The phosphate deposits of Morocco have revealed an extremely diverse environment of late maastrichtian age.[1][2] The oceans of the area were full of an abundance of fish, from bony fish like Enchodus and Stratodus to cartilaginous fish like Cretalamna, Squalicorax and Rhombodus.[1] There was also an abundance of marine reptiles, most notably the mosasaurs, with more than 10 genera alone known from this single site.[3] This possibly suggests that niche partitioning took place here, in which predators take on different niches to avoid competition with one another (for example, mosasaurs like Carniodens and Globidens had blunt teeth for crushing shellfish while Thalassotitan and Mosasaurus hunted much larger food).[1][4] Other marine reptiles include the elasmosaurid plesiosaur Zarafasaura, the sea turtle Alienochelys and the gavialoid crocodilian Ocepesuchus.[5][6]

It seems that Thalassotitan was an apex predator in its ecosystem, with evidence being digestive damage found on some of the fossils in the nearby vicinity including those of plesiosaurs, turtles, and large fish.[1] In the skies flew multiple species of pterosaurs including the azhdarchid Phosphatodraco, the nyctosauromorph Alcione and Simurghia, the nyctosaurid Barbaridactylus, and the possible pteranodontid Tethydraco.[7][8] On land three species of dinosaurs are known, these being the abelisaur Chenanisaurus, the small lambeosaurine hadrosaur Ajnabia and a so far unnamed titanosaur.[9][10] Thalassotitan lived alongside other giant mosasaurs like Prognathodon, Mosasaurus and Gavialimimus, as well as smaller mosasaurs like Xenodens, Halisaurus and Pluridens.[11][1]

See also

- Mososauroidea, the large superfamily that includes all mosasaurs

- Prognathodon, a related genus of prognathodontine mosasaur

- Ouled Abdoun Basin, the deposits that contained the Thalassotitan fossil

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Nicholas R. Longrich; Nour-Eddine Jalil; Fatima Khaldoune; Oussama Khadiri Yazami; Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola; Nathalie Bardet (2022). "Thalassotitan atrox, a giant predatory mosasaurid (Squamata) from the Upper Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco". Cretaceous Research 140: 105315. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105315. ISSN 0195-6671. Bibcode: 2022CrRes.14005315L. https://mnhn.hal.science/mnhn-03861681/document.

- ↑ Johan Yans; M'Barek Amaghzaz; Baadi Bouya; Henri Cappetta; Paola Iacumin; László Kocsis; Mustapha Mouflih; Omar Selloum et al. (2014). "First carbon isotope chemostratigraphy of the Ouled Abdoun phosphate Basin, Morocco; implications for dating and evolution of earliest African placental mammals". Gondwana Research 25 (1): 257–269. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.04.004. Bibcode: 2014GondR..25..257Y.

- ↑ Catherine R. C. Strong; Michael W. Caldwell; Takuya Konishi; Alessandro Palci (2020). "A new species of longirostrine plioplatecarpine mosasaur (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco, with a re-evaluation of the problematic taxon 'Platecarpus' ptychodon". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18 (21): 1769–1804. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1818322. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ↑ Dale A. Russell (1967). Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs. 23. New Haven: Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. pp. 240. OCLC 205385. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/88808#page/7/mode/1up.

- ↑ Nathalie Bardet; Nour-Eddine Jalil; France de Lapparent de Broin; Damien Germain; Olivier Lambert; Mbarek Amaghzaz (2013). "A giant chelonioid turtle from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco with a suction feeding apparatus unique among tetrapods". PLOS ONE 8 (7): e63586. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063586. PMID 23874378. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...863586B.

- ↑ Peggy Vincent; Nathalie Bardet; Xabier Pereda Suberbiola; Baâdi Bouya; Mbarek Amaghzaz; Saïd Meslouh (2011). "Zarafasaura oceanis, a new elasmosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco and the palaeobiogeography of latest Cretaceous plesiosaurs". Gondwana Research 19 (4): 1062–1073. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.10.005. Bibcode: 2011GondR..19.1062V.

- ↑ Nicholas R. Longrich; David M. Martill; Brian Andres (2018). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLOS Biology 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. PMID 29534059.

- ↑ Fernandes, Alexandra E.; Mateus, Octávio; Andres, Brian; Polcyn, Michael J.; Schulp, Anne S.; Gonçalves, António Olímpio; Jacobs, Louis L. (2022). "Pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Angola". Diversity 14 (9): 741. doi:10.3390/d14090741.

- ↑ Nicholas R. Longrich; Xabier Pereda Suberbiola; R. Alexander Pyron; Nour-Eddine Jalil (2020). "The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research 120: 104678. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678.

- ↑ Nicholas R. Longrich; Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola; Nour-Eddine Jalil; Fatima Khaldoune; Essaid Jourani (2017). "An abelisaurid from the latest Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research 76: 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.03.021.

- ↑ Trevor Rempert; Alexander Vinkeles Melchers; Ashley Rempert; Muhammad Haque; Andrew Armstrong (2022). "Occurrence of Mosasaurus hoffmannii Mantell, 1829 (Squamata, Mosasauridae) in the Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco". The Journal of Paleontological Sciences 22: 1–22. https://www.aaps-journal.org/pdf/JPS.C.22.0001.pdf.

Wikidata ☰ Q113620659 entry

|