Biology:Therocephalia

| Therocephalians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist's impression of two representatives of the genus Alopecognathus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | Eutheriodontia |

| Clade: | †Therocephalia Broom, 1905 |

| Families | |

|

See below | |

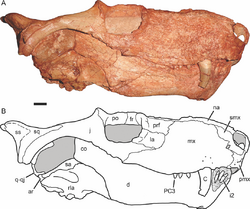

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their teeth, suggest that they were carnivores. Like other non-mammalian synapsids, therocephalians were once described as "mammal-like reptiles". Therocephalia is the group most closely related to the cynodonts, which gave rise to the mammals. This relationship takes evidence in a variety of skeletal features.

The fossils of therocephalians are numerous in the Karoo of South Africa , but have also been found in Russia , China , Tanzania, Zambia, and Antarctica. Early therocephalian fossils discovered in Middle Permian deposits of South Africa support a Gondwanan origin for the group, which seems to have spread quickly across Earth. Although almost every therocephalian lineage ended during the great Permian–Triassic extinction event, a few representatives of the subgroup called Eutherocephalia survived into the Early Triassic. Some genera belonging to this group are believed to have possessed venom, which would make them the oldest tetrapods known to have such characteristics. However, the last therocephalians became extinct by the early Middle Triassic, possibly due to climate change, along with competition with cynodonts and various groups of reptiles — mostly archosaurs and their close relatives, including archosauromorphs and archosauriforms.

Anatomy and physiology

Like the Gorgonopsia and many cynodonts, most therocephalians were presumably carnivores. The earlier therocephalians were, in many respects, as primitive as the gorgonopsians, but they did show certain advanced features. There is an enlargement of the temporal opening for broader jaw adductor muscle attachment and a reduction of the phalanges (finger and toe bones) to the mammalian phalangeal formula. The presence of an incipient secondary palate in advanced therocephalians is another feature shared with mammals. The discovery of maxilloturbinal ridges in forms such as the primitive therocephalian Glanosuchus, suggests that at least some therocephalians may have been warm-blooded.[1]

The later therocephalians included the advanced Baurioidea, which carried some theriodont characteristics to a high degree of specialization. For instance, small baurioids and the herbivorous Bauria did not have an ossified postorbital bar separating the orbit from the temporal opening—a condition typical of primitive mammals. These and other advanced features led to the long-held opinion, now rejected, that the ictidosaurs and even some early mammals arose from a baurioid therocephalian stem. Mammalian characteristics such as this seem to have evolved in parallel among a number of different therapsid groups, even within Therocephalia.[1]

Several more specialized lifestyles have been suggested for some therocephalians. Many small forms, like ictidosuchids, have been interpreted as aquatic animals. Evidence for aquatic lifestyles includes sclerotic rings that may have stabilized the eye under the pressure of water and strongly developed cranial joints, which may have supported the skull when consuming large fish and aquatic invertebrates. One therocephalian, Nothogomphodon, had large sabre-like canine teeth and may have fed on large animals, including other therocephalians. Other therocephalians such as bauriids and nanictidopids have wide teeth with many ridges similar to those of mammals, and may have been herbivores.[2]

Many small therocephalians have small pits on their snouts that probably supported vibrissae (whiskers). In 1994, the Russian paleontologist Leonid Tatarinov proposed that these pits were part of an electroreception system in aquatic therocephalians.[3] However, it is more likely that these pits are enlarged versions of the ones thought to support whiskers, or holes for blood vessels in a fleshy lip.[2] The genera Euchambersia and Ichibengops, dating from the Lopingian, particularly attract the attention of paleontologists, because the fossil skulls attributed to them have some structures which suggests that these two animals had organs for distributing venom.[4][5]

Classification

The therocephalians evolved as an early line of pre-mammalian eutheriodont therapsids, and are the sister group to the cynodonts, which includes mammals and their ancestors. Therocephalians are at least as ancient as a third large branch of therapsids, the Gorgonopsia, which they resemble in many primitive features. For example, many early therocephalians possess long canine teeth similar to those of gorgonopsians. The therocephalians, however, outlasted the gorgonopsians, persisting into the early-Middle Triassic period.

While common ancestry with cynodonts (and, thus, mammals) accounts for many similarities between these groups, some scientists believe that other similarities may be better attributed to convergent evolution, such as the loss of the postorbital bar in some forms, a mammalian phalangeal formula, and some form of a secondary palate in most taxa (see below). Therocephalians and cynodonts both survived the Permian-Triassic mass extinction; but, while therocephalians soon became extinct, cynodonts underwent rapid diversification. Therocephalians experienced a decreased rate of cladogenesis, meaning that few new groups appeared after the extinction. Most Triassic therocephalian lineages originated in the Late Permian, and lasted for only a short period of time in the Triassic,[6] going extinct during the late Anisian.[7]

Taxonomy

Some previously recognized therocephalian clades have turned out to be artificial. For example, the Scaloposauridae were classified based on fossils with mostly juvenile characteristics, but probably represent immature specimens from other known therocephalian families.

On the other hand, the aberrant therocephalian family Lycosuchidae, once identified by the presence of multiple caniniform teeth, was thought to represent an unnatural group based on a study of canine replacement in that group (van den Heever, 1980). However, subsequent analysis has exposed additional synapomorphies supporting the monophyly of this group, and Lycosuchidae is currently considered the most basal clade within a monophyletic Therocephalia (van den Heever, 1994).

Order Therapsida

- Suborder Therocephalia

- Crapartinella

- Gorynychus

- Theriodesmus

- Family Lycosuchidae

- Clade Scylacosauria

- Family Scylacosauridae

- Family Trochosuchidae

- Infraorder Eutherocephalia

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram modified from Sidor (2001) and Huttenlocker (2009):[8][9]

| Therapsida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below is a cladogram modified from an analysis published by Adam K. Huttenlocker in 2014.[10] It is based on the data matrix published by Sigurdsen et al. (2012),[11] which is itself a modified version of Huttenlocker et al. (2011).[6] Six additional characters and 22 new ingroup taxa were added to the matrix of Sigurdsen et al. (2012), resulting in a matrix that includes 58 therapsids and outgroup taxa, including 49 therocephalians, which are scored based on 135 morphological traits. Huttenlocker (2014) used this cladogram, among others, to construct an informal supertree for evaluating temporal and phylogenetic distributions of body size in Permo-Triassic eutheriodonts.[10]

| Therapsida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Evolution of mammals

- List of synapsids

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rubidge, B.S.; Sidor, C.A. (2001). "Evolutionary patterns among Permo-Triassic therapsids". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 32: 449–480. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114113. http://www11.cac.washington.edu/burkemuseum/collections/paleontology/sidor/Rubidge_Sidor2001.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ivakhnenko, M.F. (2011). "Permian and Triassic therocephals (Eutherapsida) of Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal 45 (9): 981–1144. doi:10.1134/S0031030111090012.

- ↑ Tatarinov, L.P. (1994). "On the preservation of rudimentary rostral tubular complex of crossopterygians in theriodonts and on possible development of the electroreceptor systems in some members of this group". Doklady Akademii Nauk 338 (2): 278–281.

- ↑ Benoit, J.; Norton, L.A.; Manger, P.R.; Rubidge, B.S. (2017). "Reappraisal of the envenoming capacity of Euchambersia mirabilis (Therapsida, Therocephalia) using μCT-scanning techniques". PLOS ONE 12 (2): e0172047. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172047. PMID 28187210. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1272047B.

- ↑ Field Museum (August 13, 2015). "Prehistoric carnivore dubbed 'scarface' discovered in Zambia" (Press release). Science Daily.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Huttenlocker, A.K.; Sidor, C.A.; Smith, R.M.H. (2011). "A new specimen of Promoschorhynchus (Therapsida: Therocephalia: Akidnognathidae) from the Lower Triassic of South Africa and its implications for theriodont survivorship across the Permo-Triassic boundary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31 (2): 405–421. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.546720.

- ↑ Grunert, Henrik Richard; Brocklehurst, Neil; Fröbisch, Jörg (25 March 2019). "Diversity and Disparity of Therocephalia: Macroevolutionary Patterns through Two Mass Extinctions". Scientific Reports 9 (5063): 5063. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41628-w. PMID 30911058. Bibcode: 2019NatSR...9.5063G.

- ↑ Sidor, C.A. (2001). "Simplification as a trend in synapsid cranial evolution". Evolution 55 (7): 1419–1442. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[1419:saatis2.0.co;2]. PMID 11525465. https://www11.cac.washington.edu/burkemuseum/collections/paleontology/sidor/Sidor2001.pdf.

- ↑ Huttenlocker, A. (2009). "An investigation into the cladistic relationships and monophyly of therocephalian therapsids (Amniota: Synapsida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Huttenlocker, A. K. (2014). "Body Size Reductions in Nonmammalian Eutheriodont Therapsids (Synapsida) during the End-Permian Mass Extinction". PLOS ONE 9 (2): e87553. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087553. PMID 24498335. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...987553H.

- ↑ Sigurdsen, T.; Huttenlocker, A. K.; Modesto, S. P.; Rowe, T. B.; Damiani, R. (2012). "Reassessment of the morphology and paleobiology of the therocephalian Tetracynodon darti (Therapsida), and the phylogenetic relationships of Baurioidea". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32 (5): 1113. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.688693.

Further reading

- Sigurdsen, T. (2006). "New features of the snout and orbit of a therocephalian therapsid from South Africa". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (1): 63–75.

- van den Heever, J.A. 1980. " On the validity of the therocephalian family Lycosuchidae (Reptilia, Therapsida)". Annals of the South African Museum 81: 111-125.

- van den Heever, J.A. 1994. "The cranial anatomy of the early Therocephalia (Amniota: Therapsida)." Annals of the University of Stellenbosch 1994: 1-59.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q131804 entry

|