Chemistry:Bergamottin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

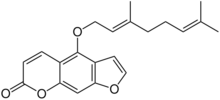

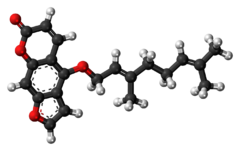

| Preferred IUPAC name

4-{[(2E)-3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl]oxy}-7H-furo[3,2-g][1]benzopyran-7-one | |

| Other names

Bergamotine

5-Geranoxypsoralen | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H22O4 | |

| Molar mass | 338.403 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 55 to 56 °C (131 to 133 °F; 328 to 329 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Bergamottin (5-geranoxypsoralen) is a natural furanocoumarin found in the pulp of pomelos and grapefruits.[1] It is also found in the peel and pulp of the bergamot orange, from which it was first isolated and from which its name is derived.

Chemistry

Bergamottin and dihydroxybergamottin are linear furanocoumarins functionalized with side chains derived from geraniol. They are inhibitors of some isoforms of the cytochrome P450 enzyme, in particular CYP3A4.[2] This prevents oxidative metabolism of certain drugs by the enzyme, resulting in an elevated concentration of drug in the bloodstream.

Under normal circumstances, the grapefruit juice effect is considered to be a negative interaction, and patients are often warned not to consume grapefruit or its juice when taking medication. However, some current research is focused on the potential benefits of cytochrome P450 inhibition.[3] Bergamottin, dihydroxybergamottin, or synthetic analogs may be developed as drugs that are targeted to increase the oral bioavailability of other drugs. Drugs that may have limited use because they are metabolized by CYP3A4 may become viable medications when taken with a CYP3A4 inhibitor because the dose required to achieve a necessary concentration in the blood would be lowered.[4]

An example of the use of this effect in current medicines is the co-administration of ritonavir, a potent inhibitor of the CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 isoforms of cytochrome P450, with other antiretroviral drugs. Although ritonavir inhibits HIV replication in its own right, its use in these treatment regimens is to enhance the bioavailability of other agents through inhibition of the enzymes that metabolize them.

Biosynthesis

Bergamottin is derived from components originating in the shikimate pathway.[5] The biosynthesis of this compound starts with the formation of the demethylsuberosin (3) product, which is formed via the alkylation of the umbelliferone (2) compound.[6] The alkylation of the umbelliferone is initiated with the use of dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, more commonly known as DMAPP. The cyclization of an alkyl group occurs to form marmesin (4), which is done in the presence of NADPH and oxygen along with a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase catalyst.[7] This process is then repeated twice more, first to remove the hydroxyisopropyl substituent from marmesin (4) to form psoralen (5), and then to add a hydroxyl group to form bergaptol (6).[8] Bergaptol (6) is next methylated with S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to form bergapten (7). The final step in this biosynthesis is the attachment of a GPP, or geranyl pyrophosphate, to the newly methylated bergapten (7) to form the target molecule bergamottin (8).

References

- ↑ Dugrand-Judek, Audray; Olry, Alexandre; Hehn, Alain; Costantino, Gilles; Ollitrault, Patrick; Froelicher, Yann; Bourgaud, Frédéric (November 2015). "The Distribution of Coumarins and Furanocoumarins in Citrus Species Closely Matches Citrus Phylogeny and Reflects the Organization of Biosynthetic Pathways". PLOS ONE 10 (11): e0142757. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142757. PMID 26558757. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1042757D.

- ↑ Basavaraj Girennavar; Shibu M. Poulose; Guddadarangavvanahally K. Jayaprakasha; Narayan G. Bhat; Bhimanagouda S. Patila (2006). "Furocoumarins from grapefruit juice and their effect on human CYP 3A4 and CYP 1B1 isoenzymes". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 14 (8): 2606–2612. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2005.11.039. PMID 16338240.

- ↑ E. C. Row; S. A. Brown; A. V. Stachulski; M. S. Lennard (2006). "Design, synthesis and evaluation of furanocoumarin monomers as inhibitors of CYP3A4". Org. Biomol. Chem. 4 (8): 1604–1610. doi:10.1039/b601096b. PMID 16604230.

- ↑ Christensen, Hege; Asberg, Anders; Holmboe, Aase-Britt; Berg, Knut Joachim (2002). "Coadministration of grapefruit juice increases systemic exposure of diltiazem in healthy volunteers". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 58 (8): 515–520. doi:10.1007/s00228-002-0516-8. PMID 12451428.

- ↑ Dewick, P. Medicinal Natural Products:A Biosynthetic Approach, 2nd ed., Wiley&Sons: West Sussex, England, 2001, p 145.

- ↑ Bisagni, E. Synthesis of psoralens and analogues. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1992, 14, 23-46.

- ↑ Voznesensky, A. I.; Schenkman, J. B. The cytochrome P450 2B4-NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase electron transfer complex is not formed by charge-pairing. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 14669-14676.

- ↑ Kent, U. M.; Lin, H. L.; Noon, K. R.; Harris, D. L.; Hollenberg, P. F. Metabolism of bergamottin by cytochromes P450 2B6 and 3A5. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 992-1005.

|