Chemistry:Molecular mechanics

Molecular mechanics uses classical mechanics to model molecular systems. The Born–Oppenheimer approximation is assumed valid and the potential energy of all systems is calculated as a function of the nuclear coordinates using force fields. Molecular mechanics can be used to study molecule systems ranging in size and complexity from small to large biological systems or material assemblies with many thousands to millions of atoms.

All-atomistic molecular mechanics methods have the following properties:

- Each atom is simulated as one particle

- Each particle is assigned a radius (typically the van der Waals radius), polarizability, and a constant net charge (generally derived from quantum calculations and/or experiment)

- Bonded interactions are treated as springs with an equilibrium distance equal to the experimental or calculated bond length

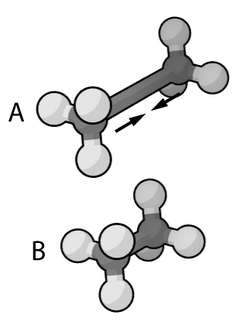

Variants on this theme are possible. For example, many simulations have historically used a united-atom representation in which each terminal methyl group or intermediate methylene unit was considered one particle, and large protein systems are commonly simulated using a bead model that assigns two to four particles per amino acid.

Functional form

The following functional abstraction, termed an interatomic potential function or force field in chemistry, calculates the molecular system's potential energy (E) in a given conformation as a sum of individual energy terms.

where the components of the covalent and noncovalent contributions are given by the following summations:

The exact functional form of the potential function, or force field, depends on the particular simulation program being used. Generally the bond and angle terms are modeled as harmonic potentials centered around equilibrium bond-length values derived from experiment or theoretical calculations of electronic structure performed with software which does ab-initio type calculations such as Gaussian. For accurate reproduction of vibrational spectra, the Morse potential can be used instead, at computational cost. The dihedral or torsional terms typically have multiple minima and thus cannot be modeled as harmonic oscillators, though their specific functional form varies with the implementation. This class of terms may include improper dihedral terms, which function as correction factors for out-of-plane deviations (for example, they can be used to keep benzene rings planar, or correct geometry and chirality of tetrahedral atoms in a united-atom representation).

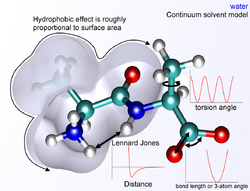

The non-bonded terms are much more computationally costly to calculate in full, since a typical atom is bonded to only a few of its neighbors, but interacts with every other atom in the molecule. Fortunately the van der Waals term falls off rapidly. It is typically modeled using a 6–12 Lennard-Jones potential, which means that attractive forces fall off with distance as r−6 and repulsive forces as r−12, where r represents the distance between two atoms. The repulsive part r−12 is however unphysical, because repulsion increases exponentially. Description of van der Waals forces by the Lennard-Jones 6–12 potential introduces inaccuracies, which become significant at short distances.[1] Generally a cutoff radius is used to speed up the calculation so that atom pairs which distances are greater than the cutoff have a van der Waals interaction energy of zero.

The electrostatic terms are notoriously difficult to calculate well because they do not fall off rapidly with distance, and long-range electrostatic interactions are often important features of the system under study (especially for proteins). The basic functional form is the Coulomb potential, which only falls off as r−1. A variety of methods are used to address this problem, the simplest being a cutoff radius similar to that used for the van der Waals terms. However, this introduces a sharp discontinuity between atoms inside and atoms outside the radius. Switching or scaling functions that modulate the apparent electrostatic energy are somewhat more accurate methods that multiply the calculated energy by a smoothly varying scaling factor from 0 to 1 at the outer and inner cutoff radii. Other more sophisticated but computationally intensive methods are particle mesh Ewald (PME) and the multipole algorithm.

In addition to the functional form of each energy term, a useful energy function must be assigned parameters for force constants, van der Waals multipliers, and other constant terms. These terms, together with the equilibrium bond, angle, and dihedral values, partial charge values, atomic masses and radii, and energy function definitions, are collectively termed a force field. Parameterization is typically done through agreement with experimental values and theoretical calculations results. Norman L. Allinger's force field in the last MM4 version calculate for hydrocarbons heats of formation with a RMS error of 0.35 kcal/mol, vibrational spectra with a RMS error of 24 cm−1, rotational barriers with a RMS error of 2.2°, C-C bond lengths within 0.004 Å and C-C-C angles within 1°.[2] Later MM4 versions cover also compounds with heteroatoms such as aliphatic amines.[3]

Each force field is parameterized to be internally consistent, but the parameters are generally not transferable from one force field to another.

Areas of application

The main use of molecular mechanics is in the field of molecular dynamics. This uses the force field to calculate the forces acting on each particle and a suitable integrator to model the dynamics of the particles and predict trajectories. Given enough sampling and subject to the ergodic hypothesis, molecular dynamics trajectories can be used to estimate thermodynamic parameters of a system or probe kinetic properties, such as reaction rates and mechanisms.

Molecular mechanics is also used within QM/MM, which allows study of proteins and enzyme kinetics. The system is divided into two regions - one of which is treated with quantum mechanics (QM) allowing breaking and formation of bonds and the rest of the protein is modeled using molecular mechanics (MM). MM alone does not allow the study of mechanisms of enzymes, which QM allows. QM also produces more exact energy calculation of the system although it is much more computationally expensive.

Another application of molecular mechanics is energy minimization, whereby the force field is used as an optimization criterion. This method uses an appropriate algorithm (e.g. steepest descent) to find the molecular structure of a local energy minimum. These minima correspond to stable conformers of the molecule (in the chosen force field) and molecular motion can be modelled as vibrations around and interconversions between these stable conformers. It is thus common to find local energy minimization methods combined with global energy optimization, to find the global energy minimum (and other low energy states). At finite temperature, the molecule spends most of its time in these low-lying states, which thus dominate the molecular properties. Global optimization can be accomplished using simulated annealing, the Metropolis algorithm and other Monte Carlo methods, or using different deterministic methods of discrete or continuous optimization. While the force field represents only the enthalpic component of free energy (and only this component is included during energy minimization), it is possible to include the entropic component through the use of additional methods, such as normal mode analysis.

Molecular mechanics potential energy functions have been used to calculate binding constants,[4][5][6][7][8] protein folding kinetics,[9] protonation equilibria,[10] active site coordinates,[6][11] and to design binding sites.[12]

Environment and solvation

In molecular mechanics, several ways exist to define the environment surrounding a molecule or molecules of interest. A system can be simulated in vacuum (termed a gas-phase simulation) with no surrounding environment, but this is usually undesirable because it introduces artifacts in the molecular geometry, especially in charged molecules. Surface charges that would ordinarily interact with solvent molecules instead interact with each other, producing molecular conformations that are unlikely to be present in any other environment. The most accurate way to solvate a system is to place explicit water molecules in the simulation box with the molecules of interest and treat the water molecules as interacting particles like those in the other molecule(s). A variety of water models exist with increasing levels of complexity, representing water as a simple hard sphere (a united-atom model), as three separate particles with fixed bond angle, or even as four or five separate interaction centers to account for unpaired electrons on the oxygen atom. As water models grow more complex, related simulations grow more computationally intensive. A compromise method has been found in implicit solvation, which replaces the explicitly represented water molecules with a mathematical expression that reproduces the average behavior of water molecules (or other solvents such as lipids). This method is useful to prevent artifacts that arise from vacuum simulations and reproduces bulk solvent properties well, but cannot reproduce situations in which individual water molecules create specific interactions with a solute that are not well captured by the solvent model, such as water molecules that are part of the hydrogen bond network within a protein.[13]

Software packages

This is a limited list; many more packages are available.

See also

References

- ↑ "Large-scale compensation of errors in pairwise-additive empirical force fields: comparison of AMBER intermolecular terms with rigorous DFT-SAPT calculations". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12 (35): 10476–10493. 2010. doi:10.1039/C002656E. PMID 20603660. Bibcode: 2010PCCP...1210476Z.

- ↑ Allinger, N. L.; Chen, K.; Lii, J.-H. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 642 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/%28SICI%291096-987X%28199604%2917%3A5/6%3C642%3A%3AAID-JCC6%3E3.0.CO%3B2-U

- ↑ Kuo‐Hsiang Chen ,Jenn‐Huei Lii, Yi Fan, Norman L. Allinger J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 2391 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jcc.20737

- ↑ "Binding of a diverse set of ligands to avidin and streptavidin: an accurate quantitative prediction of their relative affinities by a combination of molecular mechanics and continuum solvent models". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 43 (20): 3786–91. October 2000. doi:10.1021/jm000241h. PMID 11020294.

- ↑ "Computational alanine scanning of the 1:1 human growth hormone-receptor complex". J Comput Chem 23 (1): 15–27. January 2002. doi:10.1002/jcc.1153. PMID 11913381.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Predicting absolute ligand binding free energies to a simple model site". J Mol Biol 371 (4): 1118–34. August 2007. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.002. PMID 17599350.

- ↑ "Hierarchical database screenings for HIV-1 reverse transcriptase using a pharmacophore model, rigid docking, solvation docking, and MM-PB/SA". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 48 (7): 2432–44. April 2005. doi:10.1021/jm049606e. PMID 15801834.

- ↑ "Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models". Acc Chem Res 33 (12): 889–97. December 2000. doi:10.1021/ar000033j. PMID 11123888.

- ↑ "Absolute comparison of simulated and experimental protein-folding dynamics". Nature 420 (6911): 102–6. November 2002. doi:10.1038/nature01160. PMID 12422224. Bibcode: 2002Natur.420..102S.

- ↑ "Accurate, conformation-dependent predictions of solvent effects on protein ionization constants". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 (12): 4898–903. March 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700188104. PMID 17360348. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.4898B.

- ↑ "Computational prediction of native protein ligand-binding and enzyme active site sequences". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 (29): 10153–8. July 2005. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504023102. PMID 15998733. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10210153C.

- ↑ "Design of Protein-Ligand Binding Based on the Molecular-Mechanics Energy Model". J Mol Biol 380 (2): 415–24. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.001. PMID 18514737.

- ↑ Cramer, Christopher J. (2004). Essentials of computational chemistry : theories and models (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley. ISBN 0-470-09182-7. OCLC 55887497. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/55887497.

- ↑ ACEMD - GPU MD

- ↑ Ascalaph

- ↑ COSMOS

- ↑ StruMM3D (STR3DI32)

- ↑ Zodiac

Literature

- Molecular Mechanics. An American Chemical Society Publication. 1982. ISBN 978-0-8412-0885-8.

- Box VG (March 1997). "The Molecular Mechanics of Quantized Valence Bonds". J Mol Model. 3 (3): 124–41. doi:10.1007/s008940050026.

- Box VG (12 November 1998). "The anomeric effect of monosaccharides and their derivatives. Insights from the new QVBMM molecular mechanics force field". Heterocycles 48 (11): 2389–417. doi:10.3987/REV-98-504. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=10678043. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Box VG (2004). "Stereo-electronic effects in polynucleotides and their double helices". J. Mol. Struct. 689 (1–2): 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2003.10.019. Bibcode: 2004JMoSt.689...33B.

- Becker OM (2001). Computational biochemistry and biophysics. New York, N.Y.: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-0455-1.

- Mackerell AD (October 2004). "Empirical force fields for biological macromolecules: overview and issues". J Comput Chem 25 (13): 1584–604. doi:10.1002/jcc.20082. PMID 15264253.

- Schlick T (2002). Molecular modeling and simulation: an interdisciplinary guide. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95404-2.

- Krishnan Namboori; Ramachandran, K. S.; Deepa Gopakumar (2008). Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling: Principles and Applications. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-77302-3. http://www.amrita.edu/publication/computational-chemistry-and-molecular-modeling.

External links

|