Chemistry:Reactions of nitrile anions

Nitrile anions are the conjugate bases of alkyl nitriles. They undergo nucleophilic addition and substitution reactions with various electrophiles.[1]

Introduction

Although nitrile anions are functionally similar to enolates, the extra pi bond in nitrile anions provides them with a unique ketene-like geometry. Additionally, deprotonated cyanohydrins can act as masked acyl anions, giving products impossible to access with enolates alone. The mechanisms of nitrile anion addition and substitution are well understood; however, strongly basic conditions are usually required, which can limit the synthetic usefulness of the reaction.

Mechanism and stereochemistry

Generation of nitrile anions

Nitrile anions are most often generated through the action of an appropriate base. However, the pKas of nitriles span a wide range—at least 20 pKa units, depending upon substituents on the anionic carbon. Thus, the proper choice of base is usually substrate dependent. Acetonitriles containing an extra stabilizing electron-withdrawing group (such as an aromatic ring) can usually be deprotonated using hydroxide or alkoxide bases. Unstabilized nitriles, on the other hand, usually require either alkali metal amide bases (such as NaNH2) or metal alkyls (such as butyllithium) for effective deprotonation. In the latter case, competitive addition of the alkyl group to the nitrile takes place.

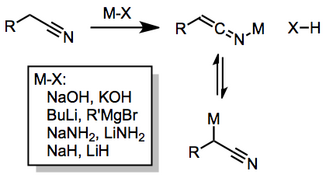

(1)

IR spectroscopic studies have demonstrated the existence of at least two tautomeric forms of the metallonitrile (see above).[2] Decreasing substitution at the anionic carbon favors the ketimine tautomer.

Polyanions of nitriles can also be generated by multiple deprotonations and these species produce polyalkylated products in the presence of alkyl electrophiles.[3]

Alternative methods to produce nitrile anions include conjugate addition to α,β-unsaturated nitriles,[4] reduction[5] of α-thioalkoxynitriles, and transmetallation[6] from α-stannylnitriles.

Reactions of nitrile anions

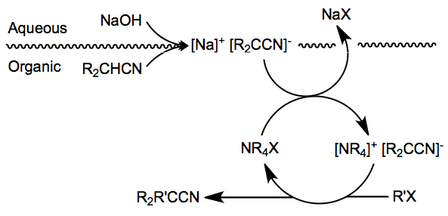

The mechanisms of reactions involving nitrile anions depend primarily on the nature of the electrophile involved. Simple alkylations take place by SN2 displacement.[7] and are subject to the usual stereoelectronic requirements of the process. Phase-transfer catalysis has been employed in alkylations of arylacetonitriles.[8] Nitrile anions can also be involved in Michael-type additions to activated double bonds and vinylation reactions with a limited number of polarized, unhindered acetylene derivatives.[9]

(2)

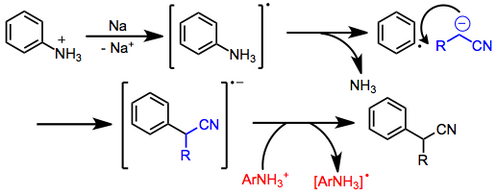

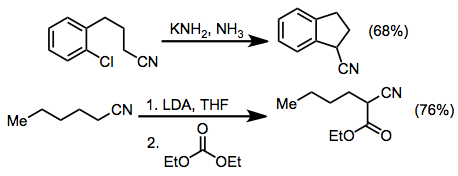

Arylation of nitrile anions is also possible and can take place through different mechanisms depending on the substrates and reaction conditions. Aryl halides lacking electron-withdrawing groups react through an elimination-addition mechanism involving benzyne intermediates.[10] Aryl phosphates and ammoniums react through the SRN1 pathway, which involves the generation of an aryl radical anion, fragmentation, and bond formation with a nucleophile.[11] Electron transfer to a second molecule of arene carries on the radical chain.

(3)

Electron-poor aromatic compounds undergo nucleophilic aromatic substitution in the presence of nitrile anions.[12]

Scope and limitations

The major problem associated with alkylation reactions employing nitrile anions is over-alkylation. In the alkylation of acetonitrile, for instance, yields of monoalkylated product are low in most cases. Two exceptions are alkylations with epoxides (the nearby negative charge of the opened epoxide wards off further alkylation) and alkylations with cyanomethylcopper(I) species. Side reactions may also present a problem; concentrations of the nitrile anion must be high to mitigate processes involving self-condensation, such as the Thorpe-Ziegler reaction. Other important side reactions include elimination of the alkyl cyanide product or alkyl halide starting material and amidine formation.

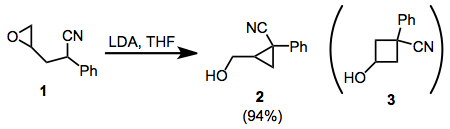

The cyclization of ω-epoxy-1-nitriles provides an interesting example of how stereoelectronic factors may override steric factors in intramolecular substitution reactions. In the cyclization of 1, for instance, only the cyclopropane product 2 is observed.[13] This result is attributed to better orbital overlap in the SN2 transition state for cyclization. 1,1-disubstituted and tetrasubstituted epoxides also follow this principle.

(4)

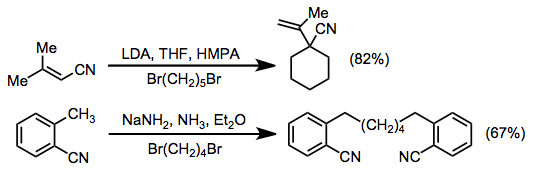

Conjugated nitriles containing γ hydrogens may be deprotonated at the γ position to give vinylogous anions. These intermediates almost always react with α selectitivity in alkylation reactions, the exception to the rule being anions of ortho-tolyl nitriles.

(5)

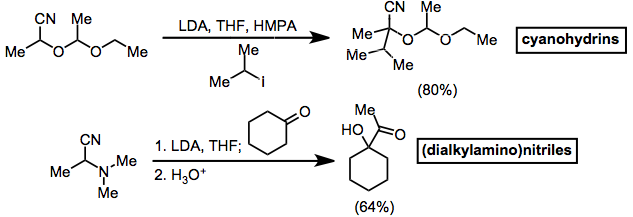

Formation of cyanohydrins from carbonyl compounds renders the former carbonyl carbon acidic. After protection of the hydroxyl group, cyanohydrins can function essentially as masked acyl anions. Because ester protecting groups are base labile, mild bases must be employed with ester-protected cyanohydrins. α-(dialkylamino)nitriles can also be used in this context.[14]

(6)

Examples of arylation[15] and acylation[16] reactions of nitriles are shown below. Although intermolecular arylations using nitrile anions result in modest yields, the intramolecular procedure efficiently gives four-, five-, and six-membered benzo-fused rings. Acylation can be accomplished using a wide variety of acyl electrophiles, including carbonates, chloroformates, esters, anhydrides, and acid chlorides.[17] In these reactions, two equivalents of base are used to drive the reaction towards acylated product—the acylated product is more acidic than the starting material.

(7)

Synthetic applications

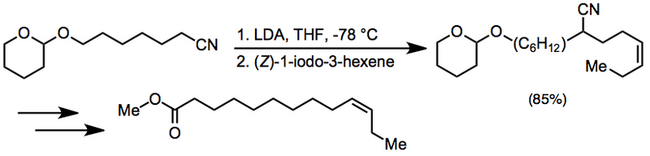

Alkylation of a nitrile anion followed by reductive decyanation is employed in the synthesis of the sex pheromone of Pazalobesia viteana.[18]

(8)

Experimental conditions and procedure

Typical conditions

The most common bases used to deprotonate nitriles are the alkali metal amides, substituted amides, and hydrides. These reagents require inert, anhydrous conditions and careful handling. Polyalkylation is a significant problem for primary or secondary nitriles; however, a number of solutions to this problem exist. Alkylation of cyanoacetates followed by decarboxylation provides one solution.[19] Acylation of primary or secondary nitriles provides a convenient entry to the starting materials for this sequence. Distillation and chromatography are only practical for the separation of mono- and dialkylated material when the molecular weight difference between the two is large.

Acylation is much more straightforward as the resulting α-cyanocarbonyl compounds are much more acidic (and less nucleophilic) than corresponding starting materials. Monoacylated products can be obtained easily.

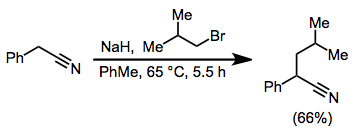

Example procedure[20]

(9)

To a suspension of 24.4 g (1.017 mol) of sodium hydride in 200 mL of anhydrous toluene was added a mixture of 122 g (1.043 mol) of phenylacetonitrile and 150 g (1.095 mol) of isobutyl bromide. The mixture was heated at 65°, at which temperature the reaction commenced. The heating mantle was removed, and the flask was cooled in order to keep the reaction from becoming too vigorous during the initial 0.5-hour reaction period. The reaction mixture was refluxed for an additional 5 hours and permitted to stand overnight. Ethanol (40 mL) was cautiously added dropwise, followed by the dropwise addition of 200 mL of water. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with benzene. The combined organic layers were washed successively with dilute acid, water, sodium carbonate solution, and water. After filtration through a layer of sodium sulfate, the benzene was evaporated and the product was fractionally distilled to afford 115 g (66%) of 2-phenyl-4-methylvaleronitrile, bp 130–134° (10 mm) [lit. (540) bp 136–138° (15 mm)].

References

- ↑ Arseniyadis, S.; Kyler, K. S.; Watt, D. S. Org. React. 1984, 31, 1-71. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or031.01

- ↑ Kruger, C. J. Organomet. Chem. 1967, 9, 125.

- ↑ Marr, G.; Ronayne, J. J. Organomet. Chem. 1973, 47, 417.

- ↑ Barrett, G.; Grattan, T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 4237.

- ↑ T. Saegusa, Y. Ito, H. Kinoshita, and S. Tomita, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979, 43, 877.

- ↑ Pereyre, M.; Odic, Y. Tetrahedron Lett., 1969, 505.

- ↑ Cope, A.; Holmes, H.; House, O. Org. React. 1957, 9, 107.

- ↑ Solaro. R.; D'Antone, S.; Chiellini, E. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 4179.

- ↑ Makosza, M. Tetrahedron Lett., 1966, 5489.

- ↑ Hoffmann, H. Dehydrobenzene and Cycloarynes, Academic Press, New York, 1967.

- ↑ Bunnett, J.; Gloor, B. J. Org. Chem. 1973, 38, 4156.

- ↑ Ross, G. Progr. Phys. Org. Chem. 1963, 1, 31.

- ↑ Corbel, B.; Durst, T. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3648.

- ↑ Stork, G.; Ozorio, A.; Leong, A. Tetrahedron Lett., 1978, 5175.

- ↑ Bunnett, J.; Skorcz, J. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 3836.

- ↑ Shimo, K.; Wakamatsu, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Nakamura, M. Kogyo Kagaku Zasshi 1959, 62, 204 [C.A., 57, 8492a (1962)].

- ↑ Smith, P.; Breen, G.; Hajek, M.; Awang, D. J. Org. Chem. 1970, 35, 2215.

- ↑ Savoia, D.; Tagliavini, E.; Trombini, C.; Umani-Ronchi, A. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3227.

- ↑ Kaiser E.; Hauser, C. J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 3873.

- ↑ Goerner, G.; Muller, H.; Corbin, J. J. Org. Chem., 24, 1561 (1959).