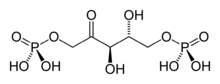

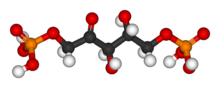

Chemistry:Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

The acid form of the RuBP anion

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,5-Di-O-phosphono-D-ribulose

| |

| Other names

Ribulose 1,5-diphosphate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H12O11P2 | |

| Molar mass | 310.088 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) is an organic substance that is involved in photosynthesis, notably as the principal CO

2 acceptor in plants.[1]:2 It is a colourless anion, a double phosphate ester of the ketopentose (ketone-containing sugar with five carbon atoms) called ribulose. Salts of RuBP can be isolated, but its crucial biological function happens in solution.[2] RuBP occurs not only in plants but in all domains of life, including Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.[3]

History

RuBP was originally discovered by Andrew Benson in 1951 while working in the lab of Melvin Calvin at UC Berkeley.[4][5] Calvin, who had been away from the lab at the time of discovery and was not listed as a co-author, controversially removed the full molecule name from the title of the initial paper, identifying it solely as "ribulose".[4][6] At the time, the molecule was known as ribulose diphosphate (RDP or RuDP) but the prefix di- was changed to bis- to emphasize the nonadjacency of the two phosphate groups.[4][5][7]

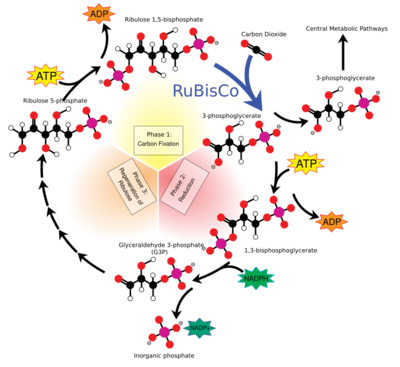

Role in photosynthesis and the Calvin-Benson Cycle

The enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (rubisco) catalyzes the reaction between RuBP and carbon dioxide. The product is the highly unstable six-carbon intermediate known as 3-keto-2-carboxyarabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate, or 2'-carboxy-3-keto-D-arabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate (CKABP).[8] This six-carbon β-ketoacid intermediate hydrates into another six-carbon intermediate in the form of a gem-diol.[9] This intermediate then cleaves into two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA) which is used in a number of metabolic pathways and is converted into glucose.[10][11]

In the Calvin-Benson cycle, RuBP is a product of the phosphorylation of ribulose-5-phosphate (produced by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate) by ATP.[11][12]

Interactions with rubisco

RuBP acts as an enzyme inhibitor for the enzyme rubisco, which regulates the net activity of carbon fixation.[13][14][15] When RuBP is bound to an active site of rubisco, the ability to activate via carbamylation with CO

2 and Mg2+ is blocked. The functionality of rubisco activase involves removing RuBP and other inhibitory bonded molecules to re-enable carbamylation on the active site.[1]:5

Role in photorespiration

Rubisco also catalyzes RuBP with oxygen (O2) in an interaction called photorespiration, a process that is more prevalent at high temperatures.[16][17] During photorespiration RuBP combines with O2 to become 3-PGA and phosphoglycolic acid.[18][19][20] Like the Calvin-Benson Cycle, the photorespiratory pathway has been noted for its enzymatic inefficiency[19][20] although this characterization of the enzymatic kinetics of rubisco have been contested.[21] Due to enhanced RuBP carboxylation and decreased rubisco oxygenation stemming from the increased concentration of CO

2 in the bundle sheath, rates of photorespiration are decreased in C

4 plants.[1]:103 Similarly, photorespiration is limited in CAM photosynthesis due to kinetic delays in enzyme activation, again stemming from the ratio of carbon dioxide to oxygen.[22]

Measurement

RuBP can be measured isotopically via the conversion of 14

CO

2 and RuBP into glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.[23] G3P can then be measured using an enzymatic optical assay.[23][24][lower-alpha 1] Given the abundance of RuBP in biological samples, an added difficulty is distinguishing particular reservoirs of the substrate, such as the RuBP internal to a chloroplast vs external. One approach to resolving this is by subtractive inference, or measuring the total RuBP of a system, removing a reservoir (e.g. by centrifugation), re-measuring the total RuBP, and using the difference to infer the concentration in the given repository.[25]

See also

- Rubisco

- Calvin-Benson cycle

- 3-Phosphoglyceric acid

- Photosynthesis

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism. Advances in Photosynthesis. 9. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 2000. doi:10.1007/0-306-48137-5. ISBN 978-0-7923-6143-5. https://archive.org/details/springer_10.1007-0-306-48137-5/.

- ↑ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. (2000). Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishing. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ↑ Tabita, F. R. (1999). "Microbial ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: A different perspective". Photosynthesis Research 60: 1–28. doi:10.1023/A:1006211417981.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sharkey, T. D. (2018). "Discovery of the canonical Calvin–Benson cycle". Photosynthesis Research 140 (2): 235–252. doi:10.1007/s11120-018-0600-2. PMID 30374727. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11120-018-0600-2.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Benson, A. A. (1951). "Identificiation of Ribulose in C14O2 Photosynthesis Products". Journal of the American Chemical Society 73 (6): 2971–2972. doi:10.1021/ja01150a545.

- ↑ Benson, A. A. (2005). "Following the path of carbon in photosynthesis: a personal story". Discoveries in Photosynthesis. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 20. pp. 795–813. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3324-9_71. ISBN 978-1-4020-3324-7. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F1-4020-3324-9_71.

- ↑ Wildman, S. G. (2002). "Along the trail from Fraction I protein to Rubisco (ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase)". Photosynthesis Research 73 (1–3): 243–250. doi:10.1023/A:1020467601966. PMID 16245127. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/A:1020467601966.pdf.

- ↑ Lorimer, G. H.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (1986). "2´-carboxy-3-keto-D-arabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate, the six-carbon intermediate of the ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase reaction". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 313 (1162): 397–407. doi:10.1098/rstb.1986.0046. Bibcode: 1986RSPTB.313..397L.

- ↑ Mauser, H.; King, W. A.; Gready, J. E.; Andrews, T. J. (2001). "CO2 Fixation by Rubisco: Computational Dissection of the Key Steps of Carboxylation, Hydration, and C−C Bond Cleavage". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 (44): 10821–10829. doi:10.1021/ja011362p. PMID 11686683.

- ↑ Kaiser, G. E.. "Light Independent Reactions". The Community College of Baltimore County, Catonsville Campus. http://faculty.ccbcmd.edu/courses/bio141/lecguide/unit7/metabolism/photosyn/lindr.html.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hatch, M. D.; Slack, C. R. (1970). "Photosynthetic CO2-Fixation Pathways". Annual Review of Plant Physiology 21: 141–162. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.21.060170.001041.

- ↑ Bartee, L.; Shriner, W.; Creech, C. (2017). "The Light Independent Reactions (aka the Calvin Cycle)". Principles of Biology. Open Oregon Educational Resources. ISBN 978-1-63635-041-7. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/mhccmajorsbio/chapter/calvin-cycle/.

- ↑ Jordan, D. B.; Chollet, R. (1983). "Inhibition of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase by substrate ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate". Journal of Biological Chemistry 258 (22): 13752–13758. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)43982-2. PMID 6417133.

- ↑ Spreitzer, R. J.; Salvucci, M. E. (2002). "Rubisco: Structure, Regulatory Interactions, and Possibilities for a Better Enzyme". Annual Review of Plant Biology 53: 449–475. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135233. PMID 12221984.

- ↑ Taylor, Thomas C.; Andersson, Inger (1997). "The structure of the complex between rubisco and its natural substrate ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate". Journal of Molecular Biology 265 (4): 432–444. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1996.0738. PMID 9034362.

- ↑ Leegood, R. C.; Edwards, G. E. (2004). "Carbon Metabolism and Photorespiration: Temperature Dependence in Relation to Other Environmental Factors". in Baker, N. R.. Photosynthesis and the Environment. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 5. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 191–221. doi:10.1007/0-306-48135-9_7. ISBN 978-0-7923-4316-5. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/0-306-48135-9_7.

- ↑ Keys, A. J.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (1977). "Effect of Temperature on Photosynthesis and Photorespiration of Wheat Leaves". Journal of Experimental Botany 28 (3): 525–533. doi:10.1093/jxb/28.3.525.

- ↑ Sharkey, T. D. (1988). "Estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves". Physiologia Plantarum 73 (1): 147–152. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1988.tb09205.x.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kebeish, R.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (2007). "Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana". Nature Biotechnology 25 (5): 593–599. doi:10.1038/nbt1299. PMID 17435746.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Leegood, R. C.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (1995). "The regulation and control of photorespiration". Journal of Experimental Botany 46: 1397–1414. doi:10.1093/jxb/46.special_issue.1397.

- ↑ Bathellier, C.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (2018). "Rubisco is not really so bad". Plant, Cell and Environment 41 (4): 705–716. doi:10.1111/pce.13149. PMID 29359811.

- ↑ Niewiadomska, E.; Borland, A. M. (2008). "Crassulacean Acid Metabolism: A Cause or Consequence of Oxidative Stress in Planta?". Progress in Botany. 69. pp. 247–266. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72954-9_10. ISBN 978-3-540-72954-9.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Latzko, E.; Gibbs, M. (1972). "Measurement of the intermediates of the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle, using enzymatic methods". Photosynthesis and Nitrogen Fixation Part B. Methods in Enzymology. 24. Academic Press. pp. 261–268. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(72)24073-3. ISBN 9780121818876.

- ↑ Latzko, E.; Gibbs, M. (1969). "Level of Photosynthetic Intermediates in Isolated Spinach Chloroplasts". Plant Physiology 44 (3): 396–402. doi:10.1104/pp.44.3.396. PMID 16657074.

- ↑ Sicher, R. C.; Bahr, J. T.; Jensen, R. G. (1979). "Measurement of Ribulose 1,5-Bisphosphate from Spinach Chloroplasts". Plant Physiology 64 (5): 876–879. doi:10.1104/pp.64.5.876. PMID 16661073.

- ↑ Note that G3P is a 3-carbon sugar so its abundance should be twice that of the 6-carbon RuBP, after accounting for rates of enzymatic catalysis.

|