Curvature of Riemannian manifolds

In mathematics, specifically differential geometry, the infinitesimal geometry of Riemannian manifolds with dimension greater than 2 is too complicated to be described by a single number at a given point. Riemann introduced an abstract and rigorous way to define curvature for these manifolds, now known as the Riemann curvature tensor. Similar notions have found applications everywhere in differential geometry of surfaces and other objects. The curvature of a pseudo-Riemannian manifold can be expressed in the same way with only slight modifications.

Ways to express the curvature of a Riemannian manifold

The Riemann curvature tensor

The curvature of a Riemannian manifold can be described in various ways; the most standard one is the curvature tensor, given in terms of a Levi-Civita connection (or covariant differentiation) [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] and Lie bracket [math]\displaystyle{ [\cdot,\cdot] }[/math] by the following formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v)w=\nabla_u\nabla_v w - \nabla_v \nabla_u w -\nabla_{[u,v]} w . }[/math]

Here [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v) }[/math] is a linear transformation of the tangent space of the manifold; it is linear in each argument. If [math]\displaystyle{ u=\partial/\partial x_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v=\partial/\partial x_j }[/math] are coordinate vector fields then [math]\displaystyle{ [u,v]=0 }[/math] and therefore the formula simplifies to

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v)w=\nabla_u\nabla_v w - \nabla_v \nabla_u w }[/math]

i.e. the curvature tensor measures noncommutativity of the covariant derivative.

The linear transformation [math]\displaystyle{ w\mapsto R(u,v)w }[/math] is also called the curvature transformation or endomorphism.

N.B. There are a few books where the curvature tensor is defined with opposite sign.

Symmetries and identities

The curvature tensor has the following symmetries:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v)=-R(v,u)^{}_{} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \langle R(u,v)w,z \rangle=-\langle R(u,v)z,w \rangle^{}_{} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v)w+R(v,w)u+R(w,u)v=0 ^{}_{} }[/math]

The last identity was discovered by Ricci, but is often called the first Bianchi identity, just because it looks similar to the Bianchi identity below. The first two should be addressed as antisymmetry and Lie algebra property respectively, since the second means that the R(u, v) for all u, v are elements of the pseudo-orthogonal Lie algebra. All three together should be named pseudo-orthogonal curvature structure. They give rise to a tensor only by identifications with objects of the tensor algebra - but likewise there are identifications with concepts in the Clifford-algebra. Let us note that these three axioms of a curvature structure give rise to a well-developed structure theory, formulated in terms of projectors (a Weyl projector, giving rise to Weyl curvature and an Einstein projector, needed for the setup of the Einsteinian gravitational equations). This structure theory is compatible with the action of the pseudo-orthogonal groups plus dilations. It has strong ties with the theory of Lie groups and algebras, Lie triples and Jordan algebras. See the references given in the discussion.

The three identities form a complete list of symmetries of the curvature tensor, i.e. given any tensor which satisfies the identities above, one could find a Riemannian manifold with such a curvature tensor at some point. Simple calculations show that such a tensor has [math]\displaystyle{ n^2(n^2-1)/12 }[/math] independent components. Yet another useful identity follows from these three:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \langle R(u,v)w,z \rangle=\langle R(w,z)u,v \rangle^{}_{} }[/math]

The Bianchi identity (often the second Bianchi identity) involves the covariant derivatives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla_uR(v,w)+\nabla_vR(w,u)+\nabla_w R(u,v)=0 }[/math]

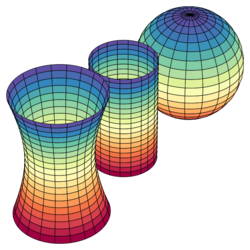

Sectional curvature

Sectional curvature is a further, equivalent but more geometrical, description of the curvature of Riemannian manifolds. It is a function [math]\displaystyle{ K(\sigma) }[/math] which depends on a section [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] (i.e. a 2-plane in the tangent spaces). It is the Gauss curvature of the [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]-section at p; here [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]-section is a locally defined piece of surface which has the plane [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] as a tangent plane at p, obtained from geodesics which start at p in the directions of the image of [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] under the exponential map at p.

If [math]\displaystyle{ v,u }[/math] are two linearly independent vectors in [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] then

- [math]\displaystyle{ K(\sigma)= K(u,v)/|u\wedge v|^2\text{ where }K(u,v)=\langle R(u,v)v,u \rangle }[/math]

The following formula indicates that sectional curvature describes the curvature tensor completely:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 6\langle R(u,v)w,z \rangle =^{}_{} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ [K(u+z,v+w)-K(u+z,v)-K(u+z,w)-K(u,v+w)-K(z,v+w)+K(u,w)+K(v,z)]-^{}_{} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ [K(u+w,v+z)-K(u+w,v)-K(u+w,z)-K(u,v+z)-K(w,v+z)+K(v,w)+K(u,z)].^{}_{} }[/math]

Or in a simpler formula:

[math]\displaystyle{ \langle R(u,v)w,z\rangle=\frac 16 \left.\frac{\partial^2}{\partial s\partial t} \left(K(u+sz,v+tw)-K(u+sw,v+tz)\right)\right|_{(s,t)=(0,0)} }[/math]

Curvature form

The connection form gives an alternative way to describe curvature. It is used more for general vector bundles, and for principal bundles, but it works just as well for the tangent bundle with the Levi-Civita connection. The curvature of an n-dimensional Riemannian manifold is given by an antisymmetric n×n matrix [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega^{}_{}=\Omega^i_{\ j} }[/math] of 2-forms (or equivalently a 2-form with values in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{so}(n) }[/math], the Lie algebra of the orthogonal group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{O}(n) }[/math], which is the structure group of the tangent bundle of a Riemannian manifold).

Let [math]\displaystyle{ e_i }[/math] be a local section of orthonormal bases. Then one can define the connection form, an antisymmetric matrix of 1-forms [math]\displaystyle{ \omega=\omega^i_{\ j} }[/math] which satisfy from the following identity

- [math]\displaystyle{ \omega^k_{\ j}(e_i)=\langle \nabla_{e_i}e_j,e_k\rangle }[/math]

Then the curvature form [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega=\Omega^i_{\ j} }[/math] is defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega=d\omega +\omega\wedge\omega }[/math].

Note that the expression "[math]\displaystyle{ \omega\wedge\omega }[/math]" is shorthand for [math]\displaystyle{ \omega^i_{\ j}\wedge\omega^j_{\ k} }[/math] and hence does not necessarily vanish. The following describes relation between curvature form and curvature tensor:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(u,v)w=\Omega(u\wedge v)w. }[/math]

This approach builds in all symmetries of curvature tensor except the first Bianchi identity, which takes form

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega\wedge\theta=0 }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \theta=\theta^i }[/math] is an n-vector of 1-forms defined by [math]\displaystyle{ \theta^i(v)=\langle e_i,v\rangle }[/math]. The second Bianchi identity takes form

- [math]\displaystyle{ D\Omega=0 }[/math]

D denotes the exterior covariant derivative

The curvature operator

It is sometimes convenient to think about curvature as an operator [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] on tangent bivectors (elements of [math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda^2(T) }[/math]), which is uniquely defined by the following identity:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \langle Q (u\wedge v),w\wedge z\rangle=\langle R(u,v)z,w \rangle. }[/math]

It is possible to do this precisely because of the symmetries of the curvature tensor (namely antisymmetry in the first and last pairs of indices, and block-symmetry of those pairs).

Further curvature tensors

In general the following tensors and functions do not describe the curvature tensor completely, however they play an important role.

Scalar curvature

Scalar curvature is a function on any Riemannian manifold, denoted variously by [math]\displaystyle{ S, R }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Sc} }[/math]. It is the full trace of the curvature tensor; given an orthonormal basis [math]\displaystyle{ \{e_i\} }[/math] in the tangent space at a point

we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ S =\sum_{i,j}\langle R(e_i,e_j)e_j,e_i\rangle=\sum_{i}\langle \text{Ric}(e_i),e_i\rangle, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Ric} }[/math] denotes the Ricci tensor. The result does not depend on the choice of orthonormal basis. Starting with dimension 3, scalar curvature does not describe the curvature tensor completely.

Ricci curvature

Ricci curvature is a linear operator on tangent space at a point, usually denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Ric} }[/math]. Given an orthonormal basis [math]\displaystyle{ \{e_i\} }[/math] in the tangent space at p we have

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Ric}(u)=\sum_{i} R(u,e_i)e_i.^{}_{} }[/math]

The result does not depend on the choice of orthonormal basis. With four or more dimensions, Ricci curvature does not describe the curvature tensor completely.

Explicit expressions for the Ricci tensor in terms of the Levi-Civita connection is given in the article on Christoffel symbols.

Weyl curvature tensor

The Weyl curvature tensor has the same symmetries as the Riemann curvature tensor, but with one extra constraint: its trace (as used to define the Ricci curvature) must vanish.

The Weyl tensor is invariant with respect to a conformal change of metric: if two metrics are related as [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{g} = f g }[/math] for some positive scalar function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \tilde{W} = W }[/math].

In dimensions 2 and 3 the Weyl tensor vanishes, but in 4 or more dimensions the Weyl tensor can be non-zero. For a manifold of constant curvature, the Weyl tensor is zero. Moreover, [math]\displaystyle{ W = 0 }[/math] if and only if the metric is locally conformal to the Euclidean metric.

Ricci decomposition

Although individually, the Weyl tensor and Ricci tensor do not in general determine the full curvature tensor, the Riemann curvature tensor can be decomposed into a Weyl part and a Ricci part. This decomposition is known as the Ricci decomposition, and plays an important role in the conformal geometry of Riemannian manifolds. In particular, it can be used to show that if the metric is rescaled by a conformal factor of [math]\displaystyle{ e^{2f} }[/math], then the Riemann curvature tensor changes to (seen as a (0, 4)-tensor):

- [math]\displaystyle{ e^{2f}\left(R+\left(\text{Hess}(f)-df\otimes df+\frac{1}{2}\|\text{grad}(f)\|^2 g\right) {~\wedge\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\;\bigcirc~} g\right) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ {~\wedge\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\;\bigcirc~} }[/math] denotes the Kulkarni–Nomizu product and Hess is the Hessian.

Calculation of curvature

For calculation of curvature

- of hypersurfaces and submanifolds see second fundamental form,

- in coordinates see the list of formulas in Riemannian geometry or covariant derivative,

- by moving frames see Cartan connection and curvature form.

- the Jacobi equation can help if one knows something about the behavior of geodesics.

References

- Kobayashi, Shoshichi; Nomizu, Katsumi (1996). Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. 1 (New ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-15733-3.

- Woods, F. S. (1901). "Space of constant curvature". The Annals of Mathematics 3 (1/4): 71–112. doi:10.2307/1967636.

Notes

|