Darboux frame

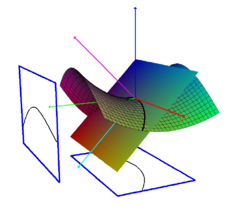

In the differential geometry of surfaces, a Darboux frame is a natural moving frame constructed on a surface. It is the analog of the Frenet–Serret frame as applied to surface geometry. A Darboux frame exists at any non-umbilic point of a surface embedded in Euclidean space. It is named after French mathematician Jean Gaston Darboux.

Darboux frame of an embedded curve

Let S be an oriented surface in three-dimensional Euclidean space E3. The construction of Darboux frames on S first considers frames moving along a curve in S, and then specializes when the curves move in the direction of the principal curvatures.

Definition

At each point p of an oriented surface, one may attach a unit normal vector u(p) in a unique way, as soon as an orientation has been chosen for the normal at any particular fixed point. If γ(s) is a curve in S, parametrized by arc length, then the Darboux frame of γ is defined by

- (the unit tangent)

- (the unit normal)

- (the tangent normal)

The triple T, t, u defines a positively oriented orthonormal basis attached to each point of the curve: a natural moving frame along the embedded curve.

Geodesic curvature, normal curvature, and relative torsion

Note that a Darboux frame for a curve does not yield a natural moving frame on the surface, since it still depends on an initial choice of tangent vector. To obtain a moving frame on the surface, we first compare the Darboux frame of γ with its Frenet–Serret frame. Let

- (the unit tangent, as above)

- (the Frenet normal vector)

- (the Frenet binormal vector).

Since the tangent vectors are the same in both cases, there is a unique angle α such that a rotation in the plane of N and B produces the pair t and u:

Taking a differential, and applying the Frenet–Serret formulas yields

where:

- κg is the geodesic curvature of the curve,

- κn is the normal curvature of the curve, and

- τr is the relative torsion (also called geodesic torsion) of the curve.

Darboux frame on a surface

This section specializes the case of the Darboux frame on a curve to the case when the curve is a principal curve of the surface (a line of curvature). In that case, since the principal curves are canonically associated to a surface at all non-umbilic points, the Darboux frame is a canonical moving frame.

The trihedron

The introduction of the trihedron (or trièdre), an invention of Darboux, allows for a conceptual simplification of the problem of moving frames on curves and surfaces by treating the coordinates of the point on the curve and the frame vectors in a uniform manner. A trihedron consists of a point P in Euclidean space, and three orthonormal vectors e1, e2, and e3 based at the point P. A moving trihedron is a trihedron whose components depend on one or more parameters. For example, a trihedron moves along a curve if the point P depends on a single parameter s, and P(s) traces out the curve. Similarly, if P(s,t) depends on a pair of parameters, then this traces out a surface.

A trihedron is said to be adapted to a surface if P always lies on the surface and e3 is the oriented unit normal to the surface at P. In the case of the Darboux frame along an embedded curve, the quadruple

- (P(s) = γ(s), e1(s) = T(s), e2(s) = t(s), e3(s) = u(s))

defines a tetrahedron adapted to the surface into which the curve is embedded.

In terms of this trihedron, the structural equations read

Change of frame

Suppose that any other adapted trihedron

- (P, e1, e2, e3)

is given for the embedded curve. Since, by definition, P remains the same point on the curve as for the Darboux trihedron, and e3 = u is the unit normal, this new trihedron is related to the Darboux trihedron by a rotation of the form

where θ = θ(s) is a function of s. Taking a differential and applying the Darboux equation yields

where the (ωi,ωij) are functions of s, satisfying

Structure equations

The Poincaré lemma, applied to each double differential ddP, ddei, yields the following Cartan structure equations. From ddP = 0,

From ddei = 0,

The latter are the Gauss–Codazzi equations for the surface, expressed in the language of differential forms.

Principal curves

Consider the second fundamental form of S. This is the symmetric 2-form on S given by

By the spectral theorem, there is some choice of frame (ei) in which (iiij) is a diagonal matrix. The eigenvalues are the principal curvatures of the surface. A diagonalizing frame a1, a2, a3 consists of the normal vector a3, and two principal directions a1 and a2. This is called a Darboux frame on the surface. The frame is canonically defined (by an ordering on the eigenvalues, for instance) away from the umbilics of the surface.

Moving frames

The Darboux frame is an example of a natural moving frame defined on a surface. With slight modifications, the notion of a moving frame can be generalized to a hypersurface in an n-dimensional Euclidean space, or indeed any embedded submanifold. This generalization is among the many contributions of Élie Cartan to the method of moving frames.

Frames on Euclidean space

A (Euclidean) frame on the Euclidean space En is a higher-dimensional analog of the trihedron. It is defined to be an (n + 1)-tuple of vectors drawn from En, (v; f1, ..., fn), where:

- v is a choice of origin of En, and

- (f1, ..., fn) is an orthonormal basis of the vector space based at v.

Let F(n) be the ensemble of all Euclidean frames. The Euclidean group acts on F(n) as follows. Let φ ∈ Euc(n) be an element of the Euclidean group decomposing as

where A is an orthogonal transformation and x0 is a translation. Then, on a frame,

Geometrically, the affine group moves the origin in the usual way, and it acts via a rotation on the orthogonal basis vectors since these are "attached" to the particular choice of origin. This is an effective and transitive group action, so F(n) is a principal homogeneous space of Euc(n).

Structure equations

Define the following system of functions F(n) → En:[1]

The projection operator P is of special significance. The inverse image of a point P−1(v) consists of all orthonormal bases with basepoint at v. In particular, P : F(n) → En presents F(n) as a principal bundle whose structure group is the orthogonal group O(n). (In fact this principal bundle is just the tautological bundle of the homogeneous space F(n) → F(n)/O(n) = En.)

The exterior derivative of P (regarded as a vector-valued differential form) decomposes uniquely as

for some system of scalar valued one-forms ωi. Similarly, there is an n × n matrix of one-forms (ωij) such that

Since the ei are orthonormal under the inner product of Euclidean space, the matrix of 1-forms ωij is skew-symmetric. In particular it is determined uniquely by its upper-triangular part (ωji | i < j). The system of n(n + 1)/2 one-forms (ωi, ωji (i<j)) gives an absolute parallelism of F(n), since the coordinate differentials can each be expressed in terms of them. Under the action of the Euclidean group, these forms transform as follows. Let φ be the Euclidean transformation consisting of a translation vi and rotation matrix (Aji). Then the following are readily checked by the invariance of the exterior derivative under pullback:

Furthermore, by the Poincaré lemma, one has the following structure equations

Adapted frames and the Gauss–Codazzi equations

Let φ : M → En be an embedding of a p-dimensional smooth manifold into a Euclidean space. The space of adapted frames on M, denoted here by Fφ(M) is the collection of tuples (x; f1,...,fn) where x ∈ M, and the fi form an orthonormal basis of En such that f1,...,fp are tangent to φ(M) at φ(x).[2]

Several examples of adapted frames have already been considered. The first vector T of the Frenet–Serret frame (T, N, B) is tangent to a curve, and all three vectors are mutually orthonormal. Similarly, the Darboux frame on a surface is an orthonormal frame whose first two vectors are tangent to the surface. Adapted frames are useful because the invariant forms (ωi,ωji) pullback along φ, and the structural equations are preserved under this pullback. Consequently, the resulting system of forms yields structural information about how M is situated inside Euclidean space. In the case of the Frenet–Serret frame, the structural equations are precisely the Frenet–Serret formulas, and these serve to classify curves completely up to Euclidean motions. The general case is analogous: the structural equations for an adapted system of frames classifies arbitrary embedded submanifolds up to a Euclidean motion.

In detail, the projection π : F(M) → M given by π(x; fi) = x gives F(M) the structure of a principal bundle on M (the structure group for the bundle is O(p) × O(n − p).) This principal bundle embeds into the bundle of Euclidean frames F(n) by φ(v;fi) := (φ(v);fi) ∈ F(n). Hence it is possible to define the pullbacks of the invariant forms from F(n):

Since the exterior derivative is equivariant under pullbacks, the following structural equations hold

Furthermore, because some of the frame vectors f1...fp are tangent to M while the others are normal, the structure equations naturally split into their tangential and normal contributions.[3] Let the lowercase Latin indices a,b,c range from 1 to p (i.e., the tangential indices) and the Greek indices μ, γ range from p+1 to n (i.e., the normal indices). The first observation is that

since these forms generate the submanifold φ(M) (in the sense of the Frobenius integration theorem.)

The first set of structural equations now becomes

Of these, the latter implies by Cartan's lemma that

where sμab is symmetric on a and b (the second fundamental forms of φ(M)). Hence, equations (1) are the Gauss formulas (see Gauss–Codazzi equations). In particular, θba is the connection form for the Levi-Civita connection on M.

The second structural equations also split into the following

The first equation is the Gauss equation which expresses the curvature form Ω of M in terms of the second fundamental form. The second is the Codazzi–Mainardi equation which expresses the covariant derivatives of the second fundamental form in terms of the normal connection. The third is the Ricci equation.

See also

- Darboux derivative

- Maurer–Cartan form

Notes

- ↑ Treatment based on Hermann's Appendix II to Cartan (1983), although he takes this approach for the affine group. The case of the Euclidean group can be found, in equivalent but slightly more advanced terms, in Sternberg (1967), Chapter VI. Note that we have abused notation slightly (following Hermann and also Cartan) by regarding fi as elements of the Euclidean space En instead of the vector space Rn based at v. This subtle distinction does not matter, since ultimately only the differentials of these maps are used.

- ↑ This treatment is from Sternberg (1964), Chapter VI, Theorem 3.1, p. 251.

- ↑ Though treated by Sternberg (1964), this explicit description is from Spivak (1999) chapters III.1 and IV.7.C.

References

- Cartan, Élie (1937). La théorie des groupes finis et continus et la géométrie différentielle traitées par la méthode du repère mobile. Gauthier-Villars.

- Cartan, É; Hermann, R. (1983). Geometry of Riemannian spaces. Math Sci Press, Massachusetts.

- Darboux, Gaston (1896) (in fr). Leçons sur la théorie génerale des surfaces. I–IV. Gauthier-Villars. https://archive.org/details/leconssurlatheor028844mbp.

- Guggenheimer, Heinrich (1977). "Chapter 10. Surfaces". Differential Geometry. Dover. ISBN 0-486-63433-7.

- Spivak, Michael (1999). A Comprehensive introduction to differential geometry (Volume 3). Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-72-1.

- Spivak, Michael (1999). A Comprehensive introduction to differential geometry (Volume 4). Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-73-X.

- Sternberg, Shlomo (1964). Lectures on differential geometry. Prentice-Hall. https://archive.org/details/lecturesondiffer0000ster.

|