Definable real number

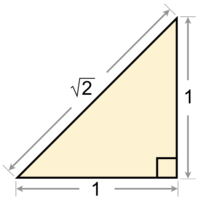

Informally, a definable real number is a real number that can be uniquely specified by its description. The description may be expressed as a construction or as a formula of a formal language. For example, the positive square root of 2, , can be defined as the unique positive solution to the equation , and it can be constructed with a compass and straightedge.

Different choices of a formal language or its interpretation give rise to different notions of definability. Specific varieties of definable numbers include the constructible numbers of geometry, the algebraic numbers, and the computable numbers. Because formal languages can have only countably many formulas, every notion of definable numbers has at most countably many definable real numbers. However, by Cantor's diagonal argument, there are uncountably many real numbers, so almost every real number is undefinable.

Constructible numbers

One way of specifying a real number uses geometric techniques. A real number is a constructible number if there is a method to construct a line segment of length using a compass and straightedge, beginning with a fixed line segment of length 1.

Each positive integer, and each positive rational number, is constructible. The positive square root of 2 is constructible. However, the cube root of 2 is not constructible; this is related to the impossibility of doubling the cube.

Real algebraic numbers

A real number is called a real algebraic number if there is a polynomial , with only integer coefficients, so that is a root of , that is, . Each real algebraic number can be defined individually using the order relation on the reals. For example, if a polynomial has 5 real roots, the third one can be defined as the unique such that and such that there are two distinct numbers less than at which is zero.

All rational numbers are constructible, and all constructible numbers are algebraic. There are numbers such as the cube root of 2 which are algebraic but not constructible.

The real algebraic numbers form a subfield of the real numbers. This means that 0 and 1 are algebraic numbers and, moreover, if and are algebraic numbers, then so are , , and, if is nonzero, .

The real algebraic numbers also have the property, which goes beyond being a subfield of the reals, that for each positive integer and each real algebraic number , all of the th roots of that are real numbers are also algebraic.

There are only countably many algebraic numbers, but there are uncountably many real numbers, so in the sense of cardinality most real numbers are not algebraic. This nonconstructive proof that not all real numbers are algebraic was first published by Georg Cantor in his 1874 paper "On a Property of the Collection of All Real Algebraic Numbers".

Non-algebraic numbers are called transcendental numbers. The best known transcendental numbers are π and e.

Computable real numbers

A real number is a computable number if there is an algorithm that, given a natural number , produces a decimal expansion for the number accurate to decimal places. This notion was introduced by Alan Turing in 1936.[1]

The computable numbers include the algebraic numbers along with many transcendental numbers including and . Like the algebraic numbers, the computable numbers also form a subfield of the real numbers, and the positive computable numbers are closed under taking th roots for each positive .

Not all real numbers are computable. Specific examples of noncomputable real numbers include the limits of Specker sequences, and algorithmically random real numbers such as Chaitin's Ω numbers.

Definability in arithmetic

Another notion of definability comes from the formal theories of arithmetic, such as Peano arithmetic. The language of arithmetic has symbols for 0, 1, the successor operation, addition, and multiplication, intended to be interpreted in the usual way over the natural numbers. Because no variables of this language range over the real numbers, a different sort of definability is needed to refer to real numbers. A real number is definable in the language of arithmetic (or arithmetical) if its Dedekind cut can be defined as a predicate in that language; that is, if there is a first-order formula in the language of arithmetic, with three free variables, such that Here m, n, and p range over nonnegative integers.

The second-order language of arithmetic is the same as the first-order language, except that variables and quantifiers are allowed to range over sets of naturals. A real that is second-order definable in the language of arithmetic is called analytical.

Every computable real number is arithmetical, and the arithmetical numbers form a subfield of the reals, as do the analytical numbers. Every arithmetical number is analytical, but not every analytical number is arithmetical. Because there are only countably many analytical numbers, most real numbers are not analytical, and thus also not arithmetical.

Every computable number is arithmetical, but not every arithmetical number is computable. For example, the limit of a Specker sequence is an arithmetical number that is not computable.

The definitions of arithmetical and analytical reals can be stratified into the arithmetical hierarchy and analytical hierarchy. In general, a real is computable if and only if its Dedekind cut is at level of the arithmetical hierarchy, one of the lowest levels. Similarly, the reals with arithmetical Dedekind cuts form the lowest level of the analytical hierarchy.

Definability in models of ZFC

A real number is first-order definable in the language of set theory, without parameters, if there is a formula in the language of set theory, with one free variable, such that is the unique real number such that holds.[2] This notion cannot be expressed as a formula in the language of set theory.

All analytical numbers, and in particular all computable numbers, are definable in the language of set theory. Thus the real numbers definable in the language of set theory include all familiar real numbers such as 0, 1, , , et cetera, along with all algebraic numbers. Assuming that they form a set in the model, the real numbers definable in the language of set theory over a particular model of ZFC form a field.

Each set model of ZFC set theory that contains uncountably many real numbers must contain real numbers that are not definable within (without parameters). This follows from the fact that there are only countably many formulas, and so only countably many elements of can be definable over . Thus, if has uncountably many real numbers, one can prove from "outside" that not every real number of is definable over .

This argument becomes more problematic if it is applied to class models of ZFC, such as the von Neumann universe. The assertion "the real number is definable over the class model " cannot be expressed as a formula of ZFC.[3][4] Similarly, the question of whether the von Neumann universe contains real numbers that it cannot define cannot be expressed as a sentence in the language of ZFC. Moreover, there are countable models of ZFC in which all real numbers, all sets of real numbers, functions on the reals, etc. are definable.[3][4]

See also

- Berry's paradox

- Constructible universe

- Entscheidungsproblem

- Ordinal definable set

- Tarski's undefinability theorem

References

- ↑ Turing, A. M. (1937), "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 2 42 (1): 230–65, doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230, http://www.abelard.org/turpap2/tp2-ie.asp

- ↑ Kunen, Kenneth (1980), An Introduction to Independence Proofs, Amsterdam: North-Holland, p. 153, ISBN 978-0-444-85401-8

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hamkins, Joel David; Linetsky, David; Reitz, Jonas (2013), "Pointwise Definable Models of Set Theory", Journal of Symbolic Logic 78 (1): 139–156, doi:10.2178/jsl.7801090

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Tsirelson, Boris (2020), "Can each number be specified by a finite text?", WikiJournal of Science 3 (1): 8, doi:10.15347/WJS/2020.008

|