Countable set

Error: no inner hatnotes detected (help). In mathematics, a set is countable if either it is finite or it can be made in one to one correspondence with the set of natural numbers.[lower-alpha 1] Equivalently, a set is countable if there exists an injective function from it into the natural numbers; this means that each element in the set may be associated to a unique natural number, or that the elements of the set can be counted one at a time, although the counting may never finish due to an infinite number of elements.

In more technical terms, assuming the axiom of countable choice, a set is countable if its cardinality (the number of elements of the set) is not greater than that of the natural numbers. A countable set that is not finite is said to be countably infinite.

The concept is attributed to Georg Cantor, who proved the existence of uncountable sets, that is, sets that are not countable; for example the set of the real numbers.

A note on terminology

Although the terms "countable" and "countably infinite" as defined here are quite common, the terminology is not universal.[1] An alternative style uses countable to mean what is here called countably infinite, and at most countable to mean what is here called countable.[2][3] To avoid ambiguity, one may limit oneself to the terms "at most countable" and "countably infinite", although with respect to concision this is the worst of both worlds.[citation needed] The reader is advised to check the definition in use when encountering the term "countable" in the literature.

The terms enumerable[4] and denumerable[5][6] may also be used, e.g. referring to countable and countably infinite respectively,[7] but as definitions vary the reader is once again advised to check the definition in use, in particular being aware of the difference with recursively enumerable.[8]

Definition

A set is countable if:

- Its cardinality is less than or equal to (aleph-null), the cardinality of the set of natural numbers .[9]

- There exists an injective function from to .[10][11]

- is empty or there exists a surjective function from to .[11]

- There exists a bijective mapping between and a subset of .[12]

- is either finite () or countably infinite.[5]

All of these definitions are equivalent.

A set is countably infinite if:

- Its cardinality is exactly .[9]

- There is an injective and surjective (and therefore bijective) mapping between and .

- has a one-to-one correspondence with .[13]

- The elements of can be arranged in an infinite sequence , where is distinct from for and every element of is listed.[14][15]

A set is uncountable if it is not countable, i.e. its cardinality is greater than .[9]

History

In 1874, in his first set theory article, Cantor proved that the set of real numbers is uncountable, thus showing that not all infinite sets are countable.[16] In 1878, he used one-to-one correspondences to define and compare cardinalities.[17] In 1883, he extended the natural numbers with his infinite ordinals, and used sets of ordinals to produce an infinity of sets having different infinite cardinalities.[18]

Introduction

A set is a collection of elements, and may be described in many ways. One way is simply to list all of its elements; for example, the set consisting of the integers 3, 4, and 5 may be denoted , called roster form.[19] This is only effective for small sets, however; for larger sets, this would be time-consuming and error-prone. Instead of listing every single element, sometimes an ellipsis ("...") is used to represent many elements between the starting element and the end element in a set, if the writer believes that the reader can easily guess what ... represents; for example, presumably denotes the set of integers from 1 to 100. Even in this case, however, it is still possible to list all the elements, because the number of elements in the set is finite. If we number the elements of the set 1, 2, and so on, up to , this gives us the usual definition of "sets of size ".

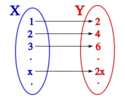

Some sets are infinite; these sets have more than elements where is any integer that can be specified. (No matter how large the specified integer is, such as , infinite sets have more than elements.) For example, the set of natural numbers, denotable by ,[lower-alpha 1] has infinitely many elements, and we cannot use any natural number to give its size. It might seem natural to divide the sets into different classes: put all the sets containing one element together; all the sets containing two elements together; ...; finally, put together all infinite sets and consider them as having the same size. This view works well for countably infinite sets and was the prevailing assumption before Georg Cantor's work. For example, there are infinitely many odd integers, infinitely many even integers, and also infinitely many integers overall. We can consider all these sets to have the same "size" because we can arrange things such that, for every integer, there is a distinct even integer: or, more generally, (see picture). What we have done here is arrange the integers and the even integers into a one-to-one correspondence (or bijection), which is a function that maps between two sets such that each element of each set corresponds to a single element in the other set. This mathematical notion of "size", cardinality, is that two sets are of the same size if and only if there is a bijection between them. We call all sets that are in one-to-one correspondence with the integers countably infinite and say they have cardinality .

Georg Cantor showed that not all infinite sets are countably infinite. For example, the real numbers cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers (non-negative integers). The set of real numbers has a greater cardinality than the set of natural numbers and is said to be uncountable.

Formal overview

By definition, a set is countable if there exists a bijection between and a subset of the natural numbers . For example, define the correspondence Since every element of is paired with precisely one element of , and vice versa, this defines a bijection, and shows that is countable. Similarly we can show all finite sets are countable.

As for the case of infinite sets, a set is countably infinite if there is a bijection between and all of . As examples, consider the sets , the set of positive integers, and , the set of even integers. We can show these sets are countably infinite by exhibiting a bijection to the natural numbers. This can be achieved using the assignments and , so that Every countably infinite set is countable, and every infinite countable set is countably infinite. Furthermore, any subset of the natural numbers is countable, and more generally:

Theorem — A subset of a countable set is countable.[20]

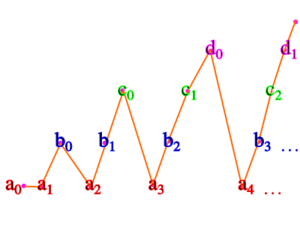

The set of all ordered pairs of natural numbers (the Cartesian product of two sets of natural numbers,

is countably infinite, as can be seen by following a path like the one in the picture:

The resulting mapping proceeds as follows:

This mapping covers all such ordered pairs.

This form of triangular mapping recursively generalizes to -tuples of natural numbers, i.e., where and are natural numbers, by repeatedly mapping the first two elements of an -tuple to a natural number. For example, can be written as . Then maps to 5 so maps to , then maps to 39. Since a different 2-tuple, that is a pair such as , maps to a different natural number, a difference between two n-tuples by a single element is enough to ensure the n-tuples being mapped to different natural numbers. So, an injection from the set of -tuples to the set of natural numbers is proved. For the set of -tuples made by the Cartesian product of finitely many different sets, each element in each tuple has the correspondence to a natural number, so every tuple can be written in natural numbers then the same logic is applied to prove the theorem.

Theorem — The Cartesian product of finitely many countable sets is countable.[21][lower-alpha 2]

The set of all integers and the set of all rational numbers may intuitively seem much bigger than . But looks can be deceiving. If a pair is treated as the numerator and denominator of a vulgar fraction (a fraction in the form of where and are integers), then for every positive fraction, we can come up with a distinct natural number corresponding to it. This representation also includes the natural numbers, since every natural number is also a fraction . So we can conclude that there are exactly as many positive rational numbers as there are positive integers. This is also true for all rational numbers, as can be seen below.

Theorem — (the set of all integers) and (the set of all rational numbers) are countable.[lower-alpha 3]

In a similar manner, the set of algebraic numbers is countable.[23][lower-alpha 4]

Sometimes more than one mapping is useful: a set to be shown as countable is one-to-one mapped (injection) to another set , then is proved as countable if is one-to-one mapped to the set of natural numbers. For example, the set of positive rational numbers can easily be one-to-one mapped to the set of natural number pairs (2-tuples) because maps to . Since the set of natural number pairs is one-to-one mapped (actually one-to-one correspondence or bijection) to the set of natural numbers as shown above, the positive rational number set is proved as countable.

Theorem — Any finite union of countable sets is countable.[24][25][lower-alpha 5]

With the foresight of knowing that there are uncountable sets, we can wonder whether or not this last result can be pushed any further. The answer is "yes" and "no", we can extend it, but we need to assume a new axiom to do so.

Theorem — (Assuming the axiom of countable choice) The union of countably many countable sets is countable.[lower-alpha 6]

For example, given countable sets , we first assign each element of each set a tuple, then we assign each tuple an index using a variant of the triangular enumeration we saw above:

We need the axiom of countable choice to index all the sets simultaneously.

Theorem — The set of all finite-length sequences of natural numbers is countable.

This set is the union of the length-1 sequences, the length-2 sequences, the length-3 sequences, each of which is a countable set (finite Cartesian product). So we are talking about a countable union of countable sets, which is countable by the previous theorem.

Theorem — The set of all finite subsets of the natural numbers is countable.

The elements of any finite subset can be ordered into a finite sequence. There are only countably many finite sequences, so also there are only countably many finite subsets.

Theorem — Let and be sets.

- If the function is injective and is countable then is countable.

- If the function is surjective and is countable then is countable.

These follow from the definitions of countable set as injective / surjective functions.[lower-alpha 7]

Cantor's theorem asserts that if is a set and is its power set, i.e. the set of all subsets of , then there is no surjective function from to . A proof is given in the article Cantor's theorem. As an immediate consequence of this and the Basic Theorem above we have:

Proposition — The set is not countable; i.e. it is uncountable.

For an elaboration of this result see Cantor's diagonal argument.

The set of real numbers is uncountable,[lower-alpha 8] and so is the set of all infinite sequences of natural numbers.

Minimal model of set theory is countable

If there is a set that is a standard model (see inner model) of ZFC set theory, then there is a minimal standard model (see Constructible universe). The Löwenheim–Skolem theorem can be used to show that this minimal model is countable. The fact that the notion of "uncountability" makes sense even in this model, and in particular that this model M contains elements that are:

- subsets of M, hence countable,

- but uncountable from the point of view of M,

was seen as paradoxical in the early days of set theory, see Skolem's paradox for more.

The minimal standard model includes all the algebraic numbers and all effectively computable transcendental numbers, as well as many other kinds of numbers.

Total orders

Countable sets can be totally ordered in various ways, for example:

- Well-orders (see also ordinal number):

- The usual order of natural numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ...)

- The integers in the order (0, 1, 2, 3, ...; −1, −2, −3, ...)

- Other (not well orders):

- The usual order of integers (..., −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...)

- The usual order of rational numbers (Cannot be explicitly written as an ordered list!)

In both examples of well orders here, any subset has a least element; and in both examples of non-well orders, some subsets do not have a least element. This is the key definition that determines whether a total order is also a well order.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Since there is an obvious bijection between and , it makes no difference whether one considers 0 a natural number or not. In any case, this article follows ISO 31-11 and the standard convention in mathematical logic, which takes 0 as a natural number.

- ↑ Proof: Observe that is countable as a consequence of the definition because the function given by is injective.[22] It then follows that the Cartesian product of any two countable sets is countable, because if and are two countable sets there are surjections and . So is a surjection from the countable set to the set and the Corollary implies is countable. This result generalizes to the Cartesian product of any finite collection of countable sets and the proof follows by induction on the number of sets in the collection.

- ↑ Proof: The integers are countable because the function given by if is non-negative and if is negative, is an injective function. The rational numbers are countable because the function given by is a surjection from the countable set to the rationals .

- ↑ Proof: Per definition, every algebraic number (including complex numbers) is a root of a polynomial with integer coefficients. Given an algebraic number , let be a polynomial with integer coefficients such that is the -th root of the polynomial, where the roots are sorted by absolute value from small to big, then sorted by argument from small to big. We can define an injection (i. e. one-to-one) function given by , where is the -th prime.

- ↑ Proof: If is a countable set for each in , then for each there is a surjective function and hence the function given by is a surjection. Since is countable, the union is countable.

- ↑ Proof: As in the finite case, but and we use the axiom of countable choice to pick for each in a surjection from the non-empty collection of surjections from to .[26] Note that since we are considering the surjection , rather than an injection, there is no requirement that the sets be disjoint.

- ↑ Proof: For (1) observe that if is countable there is an injective function . Then if is injective the composition is injective, so is countable. For (2) observe that if is countable, either is empty or there is a surjective function . Then if is surjective, either and are both empty, or the composition is surjective. In either case is countable.

- ↑ See Cantor's first uncountability proof, and also Finite intersection property for a topological proof.

Citations

- ↑ Manetti, Marco (19 June 2015) (in en). Topology. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-319-16958-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=89zyCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA26.

- ↑ Rudin 1976, Chapter 2

- ↑ Tao 2016, p. 181

- ↑ Kamke 1950, p. 2

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lang 1993, §2 of Chapter I

- ↑ Apostol 1969, p. 23, Chapter 1.14

- ↑ Thierry, Vialar (4 April 2017) (in en). Handbook of Mathematics. BoD - Books on Demand. p. 24. ISBN 978-2-9551990-1-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=RkepDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA24.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Subir Kumar (2009) (in en). First Course in Real Analysis. Academic Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-89781-90-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=n5AhsN5UQ8IC&pg=PA22.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Yaqub, Aladdin M. (24 October 2014) (in en). An Introduction to Metalogic. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-4604-0244-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=cyljCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT187.

- ↑ Singh, Tej Bahadur (17 May 2019) (in en). Introduction to Topology. Springer. p. 422. ISBN 978-981-13-6954-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=UQiZDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA422.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Katzourakis, Nikolaos; Varvaruca, Eugen (2 January 2018) (in en). An Illustrative Introduction to Modern Analysis. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-76532-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=jBFFDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT15.

- ↑ Halmos 1960, p. 91

- ↑ Kamke 1950, p. 2

- ↑ Dlab, Vlastimil; Williams, Kenneth S. (9 June 2020) (in en). Invitation To Algebra: A Resource Compendium For Teachers, Advanced Undergraduate Students And Graduate Students In Mathematics. World Scientific. p. 8. ISBN 978-981-12-1999-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=l9rrDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA8.

- ↑ Tao 2016, p. 182

- ↑ Stillwell, John C. (2010), Roads to Infinity: The Mathematics of Truth and Proof, CRC Press, p. 10, ISBN 9781439865507, https://books.google.com/books?id=XvPRBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA10, "Cantor's discovery of uncountable sets in 1874 was one of the most unexpected events in the history of mathematics. Before 1874, infinity was not even considered a legitimate mathematical subject by most people, so the need to distinguish between countable and uncountable infinities could not have been imagined."

- ↑ Cantor 1878, p. 242.

- ↑ Ferreirós 2007, pp. 268, 272–273.

- ↑ "What Are Sets and Roster Form?". 2021-05-09. https://www.expii.com/t/what-are-sets-and-roster-form-4300.

- ↑ Halmos 1960, p. 91

- ↑ Halmos 1960, p. 92

- ↑ Avelsgaard 1990, p. 182

- ↑ Kamke 1950, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Avelsgaard 1990, p. 180

- ↑ Fletcher & Patty 1988, p. 187

- ↑ Hrbacek, Karel; Jech, Thomas (22 June 1999) (in en). Introduction to Set Theory, Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. CRC Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8247-7915-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Er1r0n7VoSEC&pg=PA141.

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (June 1969), Multi-Variable Calculus and Linear Algebra with Applications, Calculus, 2 (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley + Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-00007-5, https://archive.org/details/calculus00apos

- Avelsgaard, Carol (1990), Foundations for Advanced Mathematics, Scott, Foresman and Company, ISBN 0-673-38152-8

- Cantor, Georg (1878), "Ein Beitrag zur Mannigfaltigkeitslehre", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 1878 (84): 242–248, doi:10.1515/crelle-1878-18788413, http://www.digizeitschriften.de/dms/img/?PID=GDZPPN002156806

- Ferreirós, José (2007), Labyrinth of Thought: A History of Set Theory and Its Role in Mathematical Thought (2nd revised ed.), Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-3-7643-8349-7

- Fletcher, Peter; Patty, C. Wayne (1988), Foundations of Higher Mathematics, Boston: PWS-KENT Publishing Company, ISBN 0-87150-164-3

- Halmos, Paul R. (1960), Naive Set Theory, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc Reprinted by Springer-Verlag, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-387-90092-6 (Springer-Verlag edition). Reprinted by Martino Fine Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1-61427-131-4 (Paperback edition).

- Kamke, Erich (1950), Theory of Sets, Dover series in mathematics and physics, New York: Dover, ISBN 978-0486601410

- Lang, Serge (1993), Real and Functional Analysis, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-94001-4

- Rudin, Walter (1976), Principles of Mathematical Analysis, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-054235-X

- Tao, Terence (2016). "Infinite sets" (in en). Analysis I. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. 37 (Third ed.). Singapore: Springer. pp. 181–210. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1789-6_8. ISBN 978-981-10-1789-6. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-1789-6_8.

|