Diagonal

In geometry, a diagonal is a line segment joining two vertices of a polygon or polyhedron, when those vertices are not on the same edge. Informally, any sloping line is called diagonal. The word diagonal derives from the ancient Greek διαγώνιος diagonios,[1] "from angle to angle" (from διά- dia-, "through", "across" and γωνία gonia, "angle", related to gony "knee"); it was used by both Strabo[2] and Euclid[3] to refer to a line connecting two vertices of a rhombus or cuboid,[4] and later adopted into Latin as diagonus ("slanting line").

In matrix algebra, the diagonal of a square matrix consists of the entries on the line from the top left corner to the bottom right corner.

There are also many other non-mathematical uses.

Non-mathematical uses

In engineering, a diagonal brace is a beam used to brace a rectangular structure (such as scaffolding) to withstand strong forces pushing into it; although called a diagonal, due to practical considerations diagonal braces are often not connected to the corners of the rectangle.

Diagonal pliers are wire-cutting pliers defined by the cutting edges of the jaws intersects the joint rivet at an angle or "on a diagonal", hence the name.

A diagonal lashing is a type of lashing used to bind spars or poles together applied so that the lashings cross over the poles at an angle.

In association football, the diagonal system of control is the method referees and assistant referees use to position themselves in one of the four quadrants of the pitch.

Polygons

As applied to a polygon, a diagonal is a line segment joining any two non-consecutive vertices. Therefore, a quadrilateral has two diagonals, joining opposite pairs of vertices. For any convex polygon, all the diagonals are inside the polygon, but for re-entrant polygons, some diagonals are outside of the polygon.

Any n-sided polygon (n ≥ 3), convex or concave, has total diagonals, as each vertex has diagonals to all other vertices except itself and the two adjacent vertices, or n − 3 diagonals, and each diagonal is shared by two vertices.

In general, a regular n-sided polygon has distinct diagonals in length, which follows the pattern 1,1,2,2,3,3... starting from a square.

|

|

|

|

|

Regions formed by diagonals

In a convex polygon, if no three diagonals are concurrent at a single point in the interior, the number of regions that the diagonals divide the interior into is given by

For n-gons with n=3, 4, ... the number of regions is[5]

- 1, 4, 11, 25, 50, 91, 154, 246...

This is OEIS sequence A006522.[6]

Intersections of diagonals

If no three diagonals of a convex polygon are concurrent at a point in the interior, the number of interior intersections of diagonals is given by .[7][8] This holds, for example, for any regular polygon with an odd number of sides. The formula follows from the fact that each intersection is uniquely determined by the four endpoints of the two intersecting diagonals: the number of intersections is thus the number of combinations of the n vertices four at a time.

Regular polygons

Although the number of distinct diagonals in a polygon increases as its number of sides increases, the length of any diagonal can be calculated.

In a regular n-gon with side length a, the length of the xth shortest distinct diagonal is:

This formula shows that as the number of sides approaches infinity, the xth shortest diagonal approaches the length (x+1)a. Additionally, the formula for the shortest diagonal simplifies in the case of x = 1:

If the number of sides is even, the longest diagonal will be equivalent to the diameter of the polygon's circumcircle because the long diagonals all intersect each other at the polygon's center.

Special cases include:

A square has two diagonals of equal length, which intersect at the center of the square. The ratio of a diagonal to a side is

A regular pentagon has five diagonals all of the same length. The ratio of a diagonal to a side is the golden ratio,

A regular hexagon has nine diagonals: the six shorter ones are equal to each other in length; the three longer ones are equal to each other in length and intersect each other at the center of the hexagon. The ratio of a long diagonal to a side is 2, and the ratio of a short diagonal to a side is .

A regular heptagon has 14 diagonals. The seven shorter ones equal each other, and the seven longer ones equal each other. The reciprocal of the side equals the sum of the reciprocals of a short and a long diagonal.

Polyhedrons

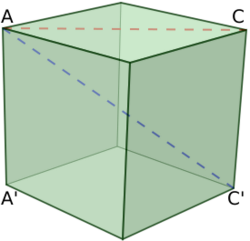

A polyhedron (a solid object in three-dimensional space, bounded by two-dimensional faces) may have two different types of diagonals: face diagonals on the various faces, connecting non-adjacent vertices on the same face; and space diagonals, entirely in the interior of the polyhedron (except for the endpoints on the vertices).

Higher dimensions

N-Cube

The lengths of an n-dimensional hypercube's diagonals can be calculated by mathematical induction. The longest diagonal of an n-cube is . Additionally, there are of the xth shortest diagonal. As an example, a 5-cube would have the diagonals:

|

Its total number of diagonals is 416. In general, an n-cube has a total of diagonals. This follows from the more general form of which describes the total number of face and space diagonals in convex polytopes.[9] Here, v represents the number of vertices and e represents the number of edges.

Matrices

For a square matrix, the diagonal (or main diagonal or principal diagonal) is the diagonal line of entries running from the top-left corner to the bottom-right corner.[10][11][12] For a matrix with row index specified by and column index specified by , these would be entries with . For example, the identity matrix can be defined as having entries of 1 on the main diagonal and zeroes elsewhere:

The trace of a matrix is the sum of the diagonal elements.

The top-right to bottom-left diagonal is sometimes described as the minor diagonal or antidiagonal.

The off-diagonal entries are those not on the main diagonal. A diagonal matrix is one whose off-diagonal entries are all zero.[13][14]

A superdiagonal entry is one that is directly above and to the right of the main diagonal.[15][16] Just as diagonal entries are those with , the superdiagonal entries are those with . For example, the non-zero entries of the following matrix all lie in the superdiagonal:

Likewise, a subdiagonal entry is one that is directly below and to the left of the main diagonal, that is, an entry with .[17] General matrix diagonals can be specified by an index measured relative to the main diagonal: the main diagonal has ; the superdiagonal has ; the subdiagonal has ; and in general, the -diagonal consists of the entries with .

A banded matrix is one for which its non-zero elements are restricted to a diagonal band. A tridiagonal matrix has only the main diagonal, superdiagonal, and subdiagonal entries as non-zero.

Geometry

By analogy, the subset of the Cartesian product X×X of any set X with itself, consisting of all pairs (x,x), is called the diagonal, and is the graph of the equality relation on X or equivalently the graph of the identity function from X to X. This plays an important part in geometry; for example, the fixed points of a mapping F from X to itself may be obtained by intersecting the graph of F with the diagonal.

In geometric studies, the idea of intersecting the diagonal with itself is common, not directly, but by perturbing it within an equivalence class. This is related at a deep level with the Euler characteristic and the zeros of vector fields. For example, the circle S1 has Betti numbers 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, and therefore Euler characteristic 0. A geometric way of expressing this is to look at the diagonal on the two-torus S1xS1 and observe that it can move off itself by the small motion (θ, θ) to (θ, θ + ε). In general, the intersection number of the graph of a function with the diagonal may be computed using homology via the Lefschetz fixed-point theorem; the self-intersection of the diagonal is the special case of the identity function.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ Strabo, Geography 2.1.36–37

- ↑ Euclid, Elements book 11, proposition 28

- ↑ Euclid, Elements book 11, proposition 38

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Polygon Diagonal." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/PolygonDiagonal.html

- ↑ Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A006522". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A006522.

- ↑ Poonen, Bjorn; Rubinstein, Michael. "The number of intersection points made by the diagonals of a regular polygon". SIAM J. Discrete Math. 11 (1998), no. 1, 135–156; link to a version on Poonen's website

- ↑ [1], beginning at 2:10

- ↑ "Counting Diagonals of a Polyhedron – the Math Doctors". https://www.themathdoctors.org/counting-diagonals-of-a-polyhedron/.

- ↑ (Bronson 1970)

- ↑ (Herstein 1964)

- ↑ (Nering 1970)

- ↑ (Herstein 1964)

- ↑ (Nering 1970)

- ↑ (Bronson 1970)

- ↑ (Herstein 1964)

- ↑ (Cullen 1966)

References

- Bronson, Richard (1970), Matrix Methods: An Introduction, New York: Academic Press

- Cullen, Charles G. (1966), Matrices and Linear Transformations, Reading: Addison-Wesley

- Herstein, I. N. (1964), Topics In Algebra, Waltham: Blaisdell Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1114541016

- Nering, Evar D. (1970), Linear Algebra and Matrix Theory (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons

External links

- Diagonals of a polygon with interactive animation

- Polygon diagonal from MathWorld.

- Diagonal of a matrix from MathWorld.

|