Earth:Solar radiation modification

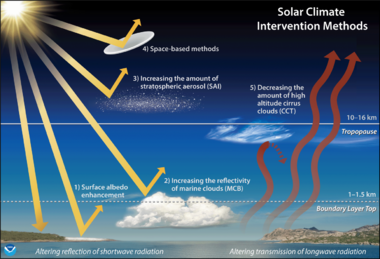

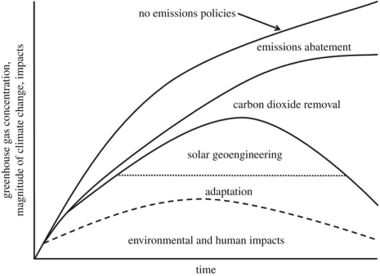

Solar radiation modification (SRM) (or solar geoengineering) is a group of large-scale approaches to reduce global warming by increasing the amount of sunlight that is reflected away from Earth and back to space. It is not intended to replace efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,[1] but rather to complement them as a potential way to limit global warming.[2]: 1489 SRM is a form of geoengineering.

The most-researched SRM method is stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), in which small reflective particles would be introduced into the upper atmosphere to reflect sunlight.[3]: 350 Other approaches include marine cloud brightening (MCB), which would increase the reflectivity of clouds over the oceans, or constructing a space sunshade or a space mirror, to reduce the amount of sunlight reaching earth.[4][5]

Climate models have consistently shown that SRM could reduce global warming and many effects of climate change,[6][7][8] including some potential climate tipping points.[9] However, its effects would vary by region and season, and the resulting climate would differ from one that had not experienced warming. Scientific understanding of these regional effects, including potential environmental risks and side effects, remains limited.[2]: 1491–1492

SRM also raises complex political, social, and ethical issues. Some worry that its development could reduce the urgency of cutting emissions. Its relatively low direct costs and technical feasibility suggest that it could, in theory, be deployed unilaterally, prompting concerns about international governance. Currently, no comprehensive global framework exists to regulate SRM research or deployment.

Interest in SRM has grown in recent years,[10] driven by continued global warming and slow progress in emissions reductions. This has led to increased scientific research, policy debate, and public discussion, although SRM remains controversial.

SRM is also known as sunlight reflection methods, solar climate engineering, albedo modification, and solar radiation management.

Context

The interest in solar radiation modification (SRM) arises from ongoing global warming, increasing risks to both human and natural systems.[12]

In principle, achieving net-zero emissions through emissions reductions and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) could halt global warming. However, emissions reductions have consistently fallen short of targets, and large-scale CDR may not be feasible.[13][14] The 2024 UN Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report said that current policies would likely lead to 3.1 °C global warming country's commitments and pledges to reduce emissions would likely lead to 1.9 °C warming.[15]: xviii

SRM aims to increase Earth's brightness (albedo) by modifying the atmosphere or surface to reflect more sunlight. A 1% increase in planetary albedo could reduce radiative forcing by 2.35 W/m², offsetting most of the warming from current greenhouse gas concentrations. A 2% increase could counteract the warming effect of a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide.[6]: 625

Unlike emissions reduction or CDR, SRM could reduce global temperatures within months of deployment.[16]: vii [7]: 14 This rapid effect means SRM could help limit the worst climate impacts while emissions reductions and CDR are scaled up. However, SRM would not reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, meaning that ocean acidification and other climate change effects would persist.

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report emphasizes that SRM is not a substitute for emissions reductions or CDR, stating: "There is high agreement in the literature that for addressing climate change risks, SRM cannot be the main policy response to climate change and is, at best, a supplement to achieving sustained net zero or net negative CO2 emission levels globally."[2]: 1489

Global dimming provides both evidence of SRM's potential efficacy and further urgency of human-caused climate change. Industrial processes have increased the quantity of aerosols in the troposphere, or lower atmosphere. This has cooled the planet, offsetting some global warming,[6]: 855–857 caused by the aerosol's reflectivity (the basis for stratospheric aerosol injection) and by increasing' clouds' reflectivity (the basis for marine cloud brightening).[6]: 860–861 As regulation has reduced tropospheric aerosols, global dimming has decreased and the planet has warmed at a faster rate.[6]: 851–853

History

In 1965, during the administration of U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, the President's Science Advisory Committee delivered Restoring the Quality of Our Environment, the first report which warned of the harmful effects of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel use. To counteract global warming, the report mentioned "deliberately bringing about countervailing climatic changes," including "raising the albedo, or reflectivity, of the Earth".[17][18]

In 1974, Russian climatologist Mikhail Budyko suggested that if global warming ever became a serious threat, it could be countered by releasing aerosols into the stratosphere. He proposed that aircraft burning sulfur could generate aerosols that would reflect sunlight away from the Earth, cooling the planet.[19][20]: 38

Along with carbon dioxide removal, SRM was discussed under the broader concept of geoengineering in a 1992 climate change report from the US National Academies.[21] The first modeled results of and review article on SRM were published in 2000.[22][23] In 2006, Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen published an influential paper arguing that, given the lack of adequate greenhouse gas emissions reductions, research on the feasibility and environmental consequences of SRM should not be dismissed.[24]

Major reports evaluating the potential benefits and risks of SRM include those by:

- The Royal Society (2009)[25]

- The US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2015, 2021)[26][16]

- The United Nations Environment Programme (2023)[7]

- The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2023)[27]

- The European Union Scientific Advice Mechanism (2024).[28][29]

In the late 2010s, SRM was increasingly distinguished from carbon dioxide removal, and "geoengineering" and similar terms were used less often.[26][3]: 550

Methods

Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI)

For stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), small particles would be introduced into the upper atmosphere to reflect sunlight and induce global dimming. Of all the proposed SRM methods, SAI has received the most sustained attention. The IPCC concluded in 2021 that SAI "is the most-researched SRM method, with high agreement that it could limit warming to below 1.5 °C."[3]: 350 This technique would replicate natural cooling phenomena observed following large volcano eruptions.[6]: 627

Sulfates are the most commonly proposed aerosol due to their natural occurrence in volcanic eruptions. Alternative substances, including calcium carbonate and titanium dioxide have also been suggested.[6]: 624

Custom-designed aircraft are considered the most feasible delivery method, with artillery and balloons occasionally proposed.[28]

SAI could produce up to 8 W/m² of negative radiative forcing.[6]: 624

The World Meteorological Organization's 2022 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion stated that "Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) has the potential to limit the rise in global surface temperatures by increasing the concentrations of particles in the stratosphere... However, SAI comes with significant risks and can cause unintended consequences."[8]: 21

A key concern with SAI is its potential to delay the recovery of the ozone layer, depending on which aerosols are used.[8]: 21

Marine cloud brightening (MCB)

Cirrus cloud thinning (CCT)

Cirrus cloud thinning (CCT) involves seeding cirrus clouds to reduce their optical thickness and decrease cloud lifetime, allowing more outgoing longwave radiation to escape into space.[6]: 628

Cirrus clouds generally have a net warming effect. By dispersing them through targeted interventions, CCT could enhance Earth's ability to radiate heat away. However, the method remains highly uncertain, as some studies suggest CCT could cause net warming rather than cooling due to complex cloud-aerosol interactions.[30]

This method is often grouped with SRM despite working primarily by increasing outgoing radiation rather than reducing incoming shortwave radiation.[6]: 624

Reflective surfaces

The IPCC describes surface-based albedo modification as "increase ocean albedo by creating microbubbles;... paint the roof of buildings white...; increase albedo of agriculture land, add reflective material to increase sea ice albedo."[6]: 624

Surface-based approaches could be considered localized and would have limited global impact.[6]: 624 While urban cooling could be achieved through reflective roofs and pavement, large-scale desert albedo modification could significantly alter regional precipitation patterns.[6]: 629 Covering glaciers with reflective materials has been proposed to slow melting, though feasibility and effectiveness at scale remains uncertain.[6]: 629

Space-based methods

Space-based SRM involves deploying mirrors, reflective particles, or shading structures at lower Earth orbit, geosynchronous orbit, or near the L1 Lagrange point between Earth and the Sun. Unlike atmospheric methods, space-based approaches would not directly interfere with Earth's climate systems.

Historically, proposals have included orbiting mirrors, space dust clouds, and electromagnetically tethered reflectors. The Royal Society (2009) and later assessments concluded that while space-based methods may be viable in the future, costs and deployment challenges make them infeasible for near-term climate intervention.[25][28]

Assessments conclude that space-based SRM is not feasible at reasonable costs.[28]: 12 The most recent IPCC Assessment Report (in 2021) did not consider these methods.[6]

Cost

SRM could have relatively low direct financial costs of deployment compared to the projected economic damages of unmitigated climate change.[2]: 1492, 1494 These costs could be on the order of billions to tens of billions of US dollars per degree of cooling.[7]: 36

Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) is the most studied and has the most cost estimates. UNEP reported a cost of $18 billion per degree,[7]: 32 although individual studies have estimated that SAI deployment could cost between $5 billion to $10 billion per year.[31]

MCB could cost, according to UNEP, $1 to 2 billion per W/m2 of negative radiative forcing,[7]: 32 which implies $1.5 to 3 billion per degree.

Cirrus cloud thinning (CCT) is even less studied, and no formal cost estimates exist.[7]: 32

Effects

Potential for reducing climate change

Modelling studies have consistently concluded that moderate SRM use would significantly reduce many of the impacts of global warming, including changes to average and extreme temperature, extreme precipitation, Arctic and terrestrial ice, cyclone intensity and frequency, and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.[6]: 625 SRM would take effect rapidly, unlike mitigation or carbon dioxide removal, making it the only known method to lower global temperatures within months.[7]: 14

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report states: "SRM could offset some of the effects of increasing greenhouse gases on global and regional climate, including the carbon and water cycles. However, there would be substantial residual or overcompensating climate change at the regional scales and seasonal timescales, and large uncertainties associated with aerosol–cloud–radiation interactions persist. The cooling caused by SRM would increase the global land and ocean CO

2 sinks, but this would not stop CO

2 from increasing in the atmosphere or affect the resulting ocean acidification under continued anthropogenic emissions."[6]: 69

SRM could partially offset agricultural losses arising from climate change.[28]: 66 The CO2 fertilization effect, which enhances plant growth under high CO2 levels, would continue under SRM. Some studies indicate that SRM might improve crop yields, while others suggest that reducing overall sunlight could slightly decrease agricultural productivity.[32][33]

Some studies suggest that SRM could prevent coral decline and mass bleaching events by reducing sea surface temperatures.[28]: 67

Regional differences

SRM would not perfectly reverse climate change effects. Differences in regional precipitation patterns, cloud cover, and atmospheric circulation could persist, with some regions experiencing overcompensation or residual warming and cooling effects.[6]: 625 This is because greenhouse gases warm throughout the globe and year, whereas SRM reflects light more effectively at low latitudes and in the hemispheric summer (due to the sunlight's angle of incidence) and only during daytime. Deployment regimes might be able to compensate for some of this heterogeneity by changing and optimizing injection rates by latitude and season.[6]: 627

Precipitation

Models indicate that SRM would reverse warming-induced changes to precipitation more effectively than changes to temperature.[6]: 625–626 Therefore, using SRM to fully return global mean temperature to a preindustrial level would overcorrect for precipitation changes. This has led to claims that it would dry the planet or even cause drought,[34] but this would depend on the intensity (i.e. radiative forcing) of SRM. Furthermore, soil moisture is more important for plants than average annual precipitation. Because SRM would reduce evaporation, it more precisely compensates for changes to soil moisture than for average annual precipitation.[6]: 627

Uncertainties and risks for the environment

Changes to monsoons

The intensity of tropical monsoons is increased by climate change and would generally be decreased by SRM and especially SAI.[6]: 624 [35]: 458–459 A net reduction in tropical monsoon intensity might manifest at moderate use of SRM, although to some degree the effect of this on humans and ecosystems would be mitigated averted heat.[35]: 458–459 Ultimately the impact would depend on the particular implementation regime.[6]: 625

Effect on sky and clouds

SRM would change the ratio between direct and indirect solar radiation, affecting plant life and solar energy. Visible light, useful for photosynthesis, is reduced proportionally more than is the infrared portion of the solar spectrum due to the mechanism of Mie scattering.[36] As a result, deployment of atmospheric SRM would affect the growth rates of plants, with the expected impact differing between canopy and subcanopy plants.[2]: 1491 [28]: 62–63, 66

Uniformly reduced net shortwave radiation would reduce solar power,[28]: 61, 66 but the real-world impact would be complex.

Stratospheric ozone

SAI would affect stratospheric ozone, which protects organisms from harmful ultraviolet radiation, with the effect depending on the characteristics of deployment.[6]: 624, 627–628 [8] Sulfates, the most commonly proposed aerosol, would delay the current recovery of stratospheric ozone.

Failure to reduce ocean acidification

SRM does not directly influence atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration and thus does not reduce ocean acidification.[2]: 1492 While not a risk of SRM per se, this indicates a critical limitation of relying on it to the exclusion of emissions reduction.

Climate model uncertainties

While climate models indicate that SRM could reduce many global warming hazards, limitations in model accuracy, aerosol-cloud interactions, and the response of regional climate systems remain key uncertainties.[6]: 624–625 Therefore, much uncertainty remains about some of SRM's likely effects.[6]: 624–625 Most of the evidence regarding SRM's expected effects comes from climate models and volcanic eruptions. Some uncertainties in climate models (such as aerosol microphysics, stratospheric dynamics, and sub-grid scale mixing) are particularly relevant to SRM and are a target for future research.[37] Volcanoes are an imperfect analogue as they release the material in the stratosphere in a single pulse, as opposed to sustained injection.[7]: 11

Risks to ecosystems

A 2023 UNEP report concluded that while an operational SRM deployment could reduce some climate hazards it would also introduce new risks to ecosystems and human societies.[7]: 15

Ecosystem impacts are not yet well understood. An EU report concluded "The potential effects on societies and especially ecosystems of SAI and SD are identified as a critical knowledge gap, with studies emphasising that the impacts and risks would vary based on the implementation scenario, geographic region and specific characteristics of ecosystems. SAI implementation may prevent some of the consequences of climate change on societies and ecosystems but it could also have unintended, and potentially unexpected, impacts."[28]: 65 Terrestrial ecosystems could experience uncertain shifts in composition and plant productivity.[28]: 62, 65

Governance

SRM raises a variety of governance issues. The IPCC lists these potential objectives of SRM governance:

(i) Guard against potential risks and harm; (ii) Enable appropriate research and development of scientific knowledge; (iii) Legitimise any future research or policymaking through active and informed public and expert community engagement; (iv) Ensure that SRM is considered only as a part of a broader, mitigation-centred portfolio of responses to climate change.[2]: 1494

Potential governance challenges

Displacement of mitigation

A common concern regarding SRM research and potential deployment is that it might reduce political and social momentum for climate change mitigation, especially the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.[2]: 1493 This hypothesis is often called "moral hazard." The likelihood and significance of moral hazard effects remain uncertain and contested among experts. Some have argued that this is unlikely and—even if true—is not a compelling reason to forgo researching and evaluating SRM if it could greatly reduce global warming and its impacts,[38] while others see the prospect as a reason to not pursue SRM.[39] Empirical evidence from game-theoretic modeling, opinion surveys, and behavioral experiments inconclusive.[28]: 99 A recent review article calls evidence for mitigation displacement "weak" but notes that these research methods fail to account for "the precise concern that real political decisions under interest-group mobilization will cut emissions too little in the presence of SRM."[40]: 355

Decisions whether to use

Another common concern with SRM is that, because its high leverage, low apparent direct costs (at least of SAI), and technical feasibility as well as issues of power and jurisdiction suggest that uni- or minilateral use is possible, without international agreement or sufficient understanding of its expected effects.[2]: 1494–1495 A key issue is under what governance regime(s) the use could be controlled, monitored, and supervised. Yet leaders of countries and other actors may disagree as to whether, how, and to what degree SRM be used. This could result in suboptimal deployments and create international tensions, especially if local harms were perceived.[2]: 1494 Experts diverge on whether uni- or minilateral use is likely and whether effective governance would be feasible[41][42][43] and on whether nonstate actors could deploy SRM at a significant scale.[44][45]

This is further complicated in two important ways. First, since SRM technologies are still emerging, there is a concern that premature regulations might be either "too restrictive or too permissive," failing to adapt adequately to future political, technological, or geophysical developments.[2]: 1494 Second, because international law is generally consensual, any governance regime would need to particularly engage and secure cooperation from countries that perceive themselves as potential users of SRM.[28]: 153

Termination

If SRM were masking significant warming and abruptly ceased without resumption within a short period (roughly a year), the climate would rapidly warm toward levels that would have existed without SRM, a phenomenon sometimes call "termination shock."[2]: 1493 A sudden and sustained termination of SRM in a world of atmospheric high greenhouse-gas concentrations would trigger rapid global temperature rise, intensified precipitation changes, sea level rise, land drying, weakened carbon sinks, and accelerated CO2 accumulation.[6]: 629 The IPCC notes that a gradual phase-out of SRM combined with mitigation would reduce the impacts of SRM's termination.[6]: 629 Furthermore, some scholars argue that this risk might be manageable, as states would have strong incentives to resume deployment if necessary, and maintaining backup SRM infrastructure could enhance system resilience and provide a buffer against abrupt cessation.[46][47]

Deployment length

A large-scale deployment of SRM would likely require a multi-decade to century-long commitment to maintain its intended climate effects.[7]: 8–10 [28]: 14 This may be necessary to achieve sustained cooling, particularly as greenhouse-gas concentrations continue to rise due to continued net emissions and carbon dioxide's long atmospheric lifetime.

Existing governance

There is currently no dedicated, formal law specifically governing SRM research, development, or deployment, though certain multilateral agreements, rules of customary international law, national and European laws, and nonbinding legal documents contain provisions that may be applicable to some SRM activities.[2]: 1493, 1495

Binding international law

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and its related treaties do not address SRM, though it could be considered within the framework of the Paris Agreement's goal to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, with efforts to stay within 1.5 °C.[28]: 163 While the UNFCCC is founded on the precautionary principle,[7]: 137 its specific implications for SRM remain uncertain.[28]: 1636–167

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea could support SRM research by permitting legitimate scientific activities and encouraging studies that assess SRM's effects on the marine environment. Its provisions to protect the marine environment may justify SRM research aimed at mitigating climate impacts on oceans, such as efforts to reduce warming or protect coral reefs. However, UNCLOS could also impose constraints on large-scale outdoor activities, particularly if activities under a state's jurisdiction risk polluting or harming marine ecosystems. Additionally, because SRM does not directly address ocean acidification, its alignment with UNCLOS' environmental protection objectives remains uncertain.[16]: 101–102

The Environmental Modification Convention is the only international treaty that directly regulates deliberate manipulation of natural processes with "widespread, long-lasting or severe effects" of a transboundary nature. SRM falls within ENMOD's definition of environmental modification techniques and is therefore subject to its prohibition on military or hostile use. At the same time, the treaty states that it "shall not hinder the use of environmental modification techniques for peaceful purposes." ENMOD also encourages the exchange of information and international cooperation on peaceful environmental modification, with parties "in a position to do so" expected to support scientific and economic collaboration.[28]: 162

The Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and its Montreal Protocol obligate parties to take measures to reduce or prevent human activities that could have harmful effects from modifying the ozone layer, which some forms of SAI might have. Article 2 specifically requires states to cooperate to "protect human health and the environment against adverse effects resulting or likely to result from human activities which modify or are likely to modify the ozone layer."[28]: 162

The rule of prevention of transboundary harm under customary international law obligates states to prevent significant transboundary environmental harm and to reduce the risks thereof. This rule would be relevant to large-scale outdoor SRM activities, if they were to present risk of causing significant transboundary harm on human health, ecosystems, or the climate system. Under this rule, states must exercise due diligence to prevent significant transboundary environmental harm by conducting environmental impact assessments, notifying and consulting affected states, and cooperating in good faith to mitigate risks. Failure to meet these obligations could result in state responsibility for harm caused by activities within their jurisdiction. Scholars have debated whether SRM research and deployment should be held to different legal standards. Furthermore, international cooperation obligations may require states to collaborate on impact assessments, data sharing, and governance mechanisms.[28]: 156–161

Nonbinding international law

The International Law Commission developed draft guidelines for the protection of the atmosphere. One guidelines state, in its entirety:

Activities aimed at intentional large-scale modification of the atmosphere should only be conducted with prudence and caution, and subject to any applicable rules of international law, including those relating to environmental impact assessment.[48]

The Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity have made several decisions regarding "climate related geoengineering," which would include SRM. That of 2010 established "a comprehensive non-binding normative framework"[49]: 106 for "climate-related geoengineering activities that may affect biodiversity," requesting that such activities be justified by the need to gather specific scientific data, undergo prior environmental assessment, be subject to effective regulatory oversight.[16]: 96–97 [28]: 161–162 The Parties' 2016 decision called for "more transdisciplinary research and sharing of knowledge... in order to better understand the impacts of climate-related geoengineering."[28]: 161–162 [50]

National and subnational law

As with international law, existing areas of national and subnational law—such as environmental regulation, tort liability, and intellectual property—would govern certain aspects of SRM. For example, in the US,[16]: 91–96 under the National Environmental Protection Act and similar state laws, federally sponsored or authorized outdoor SRM research may require environmental review if it poses risk of significant physical impacts, though small-scale experiments are often exempt. Several federal regulatory statutes, including the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Ocean Dumping Act, and Federal Aviation Administration rules, may apply to SRM field experiments depending on their design, particularly regarding emissions into air or water and the use of aircraft. Outdoor experiments could also expose researchers to tort liability under state common law theories such as negligence, strict liability, or nuisance, though plaintiffs may face challenges in proving causation and demonstrating that potential harms outweigh societal benefits. Intellectual property law, particularly patent rights, may influence the development of SRM technologies by incentivizing innovation while potentially limiting access, although current patent activity in the field remains limited.

The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources of Mexico announced in 2023 that it would prohibit SRM experiments in that country.[51]

In 2025, several US states implemented or are considering prohibitions on "geoengineering." However, these are aimed not at SRM per se but at purported chemtrails or weather modification.[52]

Guidelines and principles

Groups of academics, research networks, and the broader SRM research community have developed multiple sets of principles or guidelines to help govern SRM activities.[16]: 106 [28]: 134 For example, the Oxford Principles (which address SRM and carbon dioxide removal as "geoengineering") are the most prominent:[27]: 21

- Geoengineering to be regulated as a public good;

- Public participation in geoengineering decision making;

- Disclosure of geoengineering research and open publication of results;

- Independent assessment of impacts; and

- Governance before deployment.[53]

More recently, the American Geophysical Union issued an ethical framework for researching "climate intervention" (again, SRM and carbon dioxide removal).[54][55]

Support for research

Support for SRM research has come from scientists, international organizations, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). A central argument in support of SRM research is that there are large and immediate risks from climate change, and SRM is the only known way to quickly stop (or reverse) warming.

An article in MIT Technology Review stated in 2017: "Few serious scientists would argue that we should begin deploying geoengineering anytime soon."[56]

Campaigners have claimed that the fossil fuels lobby advocates for SRM research.[57][58] However, research by information hub SRM360 and others has "not found evidence that private fossil fuel interests are funding or promoting SRM, and many recipients of SRM funding explicitly state that they will not accept funding from fossil fuel sources."[59]

Scientists and other academics

Two sign-on letters in 2023 from scientists and other experts called for expanded "responsible SRM research". One requested to "objectively evaluate the potential for SRM to reduce climate risks and impacts, to understand and minimize the risks of SRM approaches, and to identify the information required for governance". It was endorsed by "more than 110 physical and biological scientists studying climate and climate impacts about the role of physical sciences research."[60] Another called for "balance in research and assessment of solar radiation modification" and was endorsed by about 150 experts, mostly scientists.[61]

Furthermore, in a publication of 2025 James Hansen and others said "Research on purposeful global cooling should be pursued, as recommended by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences".[38]

Government and other scientific bodies

Scientific and other large organizations that have called for further research on SRM include:

- In the UK: the Royal Society,[25] the Institution of Mechanical Engineers,[62] and the editorial board of Nature[63]

- In Australia: the Office of the Chief Scientist[64]

- In the Netherlands: Netherlands' scientific assessment institute[65]

- In the United States: the US National Academies,[26][16] the American Geophysical Union,[66] the American Meteorological Society, the U.S. Global Change Research Program,[67] and the Council on Foreign Relations[68]

- International organizations: the World Climate Research Programme[69] and reports from the UN Environment Programme[7] and the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization[27]

- In the European Union: the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors[29]

Few countries have an explicit governmental position on SRM. Those that do, such as the United Kingdom,[70] Canada,[71] and Germany,[72]: 58 support some SRM research even if they do not see it as a current climate policy option. For example, the German Federal Government does have an explicit position on SRM and stated in 2023 in a strategy document climate foreign policy: "Due to the uncertainties, implications and risks, the German Government is not currently considering solar radiation management (SRM) as a climate policy option". The document also stated: "Nonetheless, in accordance with the precautionary principle we will continue to analyse and assess the extensive scientific, technological, political, social and ethical risks and implications of SRM, in the context of technology-neutral basic research as distinguished from technology development for use at scale".[72]: 58 As of 2025 the federal US government does not have a policy on SRM.[73]

Under the World Climate Research Programme there is a Lighthouse Activity called Research on Climate Intervention as of 2024. This will include research on possible large-scale carbon dioxide removal and SRM.[69]

Nongovernmental organizations

Some nongovernmental organizations actively support SRM research and governance dialogues.

The Degrees Initiative is a UK registered charity, established to build capacity in developing countries to evaluate SRM.[74] It works toward "changing the global environment in which SRM is evaluated, ensuring informed and confident representation from developing countries."[74] A researcher from the German NGO Geoengineering Monitor is of the opinion that this charity is "imposing its research agenda onto the Global South" and is "predominantly funded by foundations run by technology and finance billionaires based in the Global North".[75]

Operaatio Arktis is a Finnish youth climate organisation that supports research into solar radiation modification alongside mitigation and carbon sequestration as a potential means to preserve polar ice caps and prevent tipping points.[76]

SilverLining is an American organization that advances SRM research as part of "climate interventions to reduce near-term climate risks and impacts."[77] It is funded by "philanthropic foundations and individual donors focused on climate change".[77][78] One of their funders is Quadrature Climate Foundation which "plans to provide $40 million for work in this field over the next three years" (as of 2024).[79]

The Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering advances "just and inclusive deliberation" regarding SRM, in particular by engaging civil society organizations in the Global South and supporting a broader conversation on SRM governance.[80] The Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative catalyzed governance of SRM and carbon dioxide removal,[81] although it ended operations in 2023.

The Climate Overshoot Commission is a group of global, eminent, and independent figures.[82] It investigated and developed a comprehensive strategy to reduce climate risks. The Commission recommended additional research on SRM alongside a moratorium on deployment and large-scale outdoor experiments. It also concluded that "governance of SRM research should be expanded".[83]: 15

SRM research initiatives, or non-profit knowledge hubs, include for example SRM360 which is "supporting an informed, evidence-based discussion of sunlight reflection methods (SRM)".[84] Funding comes from the LAD Climate Fund.[85][86]

Another example is Reflective, which is "a philanthropically-funded initiative focused on sunlight reflection research and technology development".[87] Their funding is "entirely by grants or donations from a number of leading philanthropies focused on addressing climate change": Outlier Projects, Navigation Fund, Astera Institute, Open Philanthropy, Crankstart, Matt Cohler, Richard and Sabine Wood.[87]

Research funding

Through 2024, roughly $200 million had been spent on SRM research, with the annual rate having increased to more than $30 million in recent years.[59] As of May 2025, $164 more has been committed for 2025-2029.

Governments

As of 2025, 42% of research funding come from governments.[59] Countries that have funded SRM research include the U.S., U.K., Australia, Argentina, Germany, China, Finland, Norway, and Japan, as well as the European Union.[88]

NOAA in the United States spent $22 million USD from 2019 to 2022, with only a few outdoor tests carried out.[89] As of 2024, NOAA provides about $11 million USD a year through their solar geoengineering research program.[79]

In 2025, the UK government invested more than 60 million pounds on SRM research, which includes outdoor geoengineering experiments.[90] In late 2024, the Advanced Research and Invention Agency, a British funding agency, announced that research funds totaling 57 million pounds (about $75 million USD) will be made available to support projects which explore "Climate Cooling".[91] This includes outdoor experiments. Successful applicants were announced in 2025.[92] The program, together with another 10 million pound program by Natural Environment Research Council makes the UK "one of the biggest funders of geoengineering research in the world".[90][93]

Philanthropies

As of 2025, 48% of research funding has come from philanthropy.[59] The largest donors are the SImons Foundation, Quadrature Climate Foundation, and Open Philanthropy. According to Bloomberg News, as of 2024 several American billionaires are funding research into SRM.[94] The article listed Mike Schroepfer, Sam Altman, Matt Cohler, Rachel Pritzker, Bill Gates, and Dustin Moskovitz as being notable geoengineering research supporters.[94]

Opposition to deployment and research

Opposition to SRM research and deployment has come from activist non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academics,[43] and U.S. Republican policymakers.[95][96][97][98] Common concerns include that SRM could undermine efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, prove difficult to govern at a global scale, or trigger international tensions and conflict. Opponents often emphasize that strong mitigation would also deliver public health and environmental co-benefits, such as reduced air pollution, which might be deprioritized if SRM gains traction.[99]

Advocacy groups

The ETC Group, an NGO focused on the socioeconomic and ecological impacts of emerging technologies, was a pioneer in opposing SRM research.[100] It was later joined by the Heinrich Böll Foundation,[101] a German political organization affiliated with the Green Party, and the Center for International Environmental Law.[102] Climate Action Network, a global network of organizations promoting climate action, also opposes outdoor experiments and the use of SRM.[99]

In 2021, researchers at Harvard University paused plans for a small-scale SRM field experiment in Sweden after opposition from the Saami Council, an Indigenous advocacy group. The Council objected to a test flight over their ancestral land.[103][104] Although the flight would not have released any material, the Saami Council criticized the lack of consultation and expressed broader concerns about the ethics and risks of SRM.

Academics

A coalition of scholars and advocates has proposed an "International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering," calling for governments to prohibit funding, experimentation, patenting, deployment, and institutional legitimization of SRM, which they argue is too risky, politically ungovernable, and likely to undermine mitigation. As of December 2024, their effort has been supported by nearly 540 academics[105] and 60 advocacy organizations.[106] Although the campaign describes the former as "scientists,"[107] the large majority is social scientists. Their campaign was launched with an essay in an academic journal, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews (WIREs): Climate Change.[43] The initiative does not disclose its ultimate funding source.[108]

The same journal later published two follow-up items. First, the publisher, Wiley, attached an editorial note to the essay acknowledging a conflict of interest in the peer review process. Mike Hulme, the journal's editor-in-chief who oversaw the review of the article for WIREs Climate Change, had co-authored an earlier version of the article, which had been rejected by another journal. Wiley concluded that this was a conflict of interest. Hulme resigned as editor-in-chief during the publisher's investigation.[109]

Second, in a published response, a group of scholars argue that the "Non-Use Agreement" campaign misrepresents the state of research and exaggerates the risks of experimentation. They contend that such an agreement would stifle legitimate scientific inquiry, marginalize voices from developing countries, and hinder the responsible governance of emerging technologies.[110]

U.S. Republican policymakers

Since 2024, and especially following the re-election of Donald Trump as U.S. President, lawmakers in at least 28 U.S. states have introduced or supported bills to prohibit SRM or related practices.[111] These efforts often target SRM[95] and weather modification[96] specifically. These bills are influenced by the chemtrails conspiracy theory.[97] In 2024, Tennessee enacted such a bill, approved along party lines[112] and signed into law by Governor Bill Lee.[113] The next year, Florida enacted a similar one, upon signing by Governor Ron DeSantis.[114] US Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene announced her plan to introduce a similar federal bill that would make outdoor SRM or weather modification activities a felony.[115]

Members of the Trump administration have endorsed the effort. Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Trump administration, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. posted on X: "24 States move to ban geoengineering our climate by dousing our citizens, our waterways and landscapes with toxins. This is a movement every MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) needs to support. HHS will do its part."[97] When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took action against the startup Make Sunsets (see below), EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin was quoted in the agency's press release, stating: "The idea that individuals, supported by venture capitalists, are putting criteria air pollutants into the air to sell 'cooling' credits shows how climate extremism has overtaken common sense."[116]

Society and culture

Commercial actors

Make Sunsets[117] is a private startup that sells "cooling credits" for its small-scale SRM activities, claiming that each US$10 credit offsets the warming effect of one ton of carbon dioxide for a year.[118] The firm releases balloons containing helium and sulfur dioxide. Make Sunsets conducted some of its first activities in Mexico, causing the Mexican government announced its intention to prohibit SRM experiments within its borders.[119] Even those who advocate for more research into SRM criticize Make Sunsets' undertaking.[120] In April 2025, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency demanded information from the startup regarding its releases of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere.[116]

Public awareness and opinions

Overall, public opinion on SRM is nascent, ambivalent, and context-dependent, with greater support for research than for deployment.[28]: 100 Public awareness of SRM remains low globally, with 75–80% of respondents in recent multi-country surveys reporting little to no familiarity.[28]: 96 Despite this, social science research on public attitudes toward SRM is growing and diversifying, although the UK, US, and Germany still dominate the existing academic literature.[28]: 92 Public opinion in the Global South remains less well examined, though several studies thus far consistently find greater openness to SRM there, where climate impacts are perceived as more immediate.[28]: 100–101 Methodologically, research has shifted toward large-scale surveys, but concerns remain about the durability of preferences given low baseline knowledge.[28]: 98

Across studies, public views are shaped by values, perceived climate risk, and how SRM is framed. Common concerns include the fear of displacing mitigation, the unnaturalness of intervening in climate systems, justice and equity, and a desire to inform and consult with the public prior to use.[28]: 99–100 SRM is generally viewed less favorably than greenhouse-gas emissions reduction and carbon dioxide removal.[28]: 99 Europeans tend to be more averse, especially in central and northern countries (e.g. Germany, Austria, Switzerland), while southern European and Global South populations are more accepting, particularly when facing high climate vulnerability.[28]: 98 Some studies also highlight links between SRM and conspiracy theories, such as chemtrails, which can further complicate public understanding.[28]: 100

Chemtrail conspiracy theory

References

- ↑ Helwegen, Koen G.; Wieners, Claudia E.; Frank, Jason E.; Dijkstra, Henk A. (2019-07-15). "Complementing CO2 emission reduction by solar radiation management might strongly enhance future welfare" (in English). Earth System Dynamics 10 (3): 453–472. doi:10.5194/esd-10-453-2019. ISSN 2190-4979. Bibcode: 2019ESD....10..453H. https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/10/453/2019/esd-10-453-2019.html. "even if successful, SRM can not replace but only complement CO2 abatement.".

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021). Climate Change 2021: Mitigation of Climate Change – Working Group III Contribution. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ipcc (2022-06-09). Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009157940.006. ISBN 978-1-009-15794-0. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009157940/type/book.

- ↑ Feingold, Graham; Ghate, Virendra P.; Russell, Lynn M.; Blossey, Peter; Cantrell, Will; Christensen, Matthew W.; Diamond, Michael S.; Gettelman, Andrew et al. (22 March 2024). "Physical science research needed to evaluate the viability and risks of marine cloud brightening". Science Advances 10 (12). doi:10.1126/sciadv.adi8594. PMID 38507486. Bibcode: 2024SciA...10I8594F.

- ↑ Feinberg, Alec (12 February 2024). [https:/www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/12/2/26# "Annual Solar Geoengineering: Mitigating Yearly Global Warming Increases"]. Climate 12 (2): 26. https:/www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/12/2/26#.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis – Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 "One Atmosphere: An Independent Expert Review on Solar Radiation Modification Research and Deployment" (in en). 2023. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/Solar-Radiation-Modification-research-deployment.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 World Meteorological Organization (2022). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2022. World Meteorological Organization. https://csl.noaa.gov/assessments/ozone/2022/downloads/.

- ↑ Futerman, Gideon; Adhikari, Mira; Duffey, Alistair; Fan, Yuanchao; Irvine, Peter; Gurevitch, Jessica; Wieners, Claudia (2023-10-10). "The interaction of Solar Radiation Modification and Earth System Tipping Elements" (in English). EGUsphere: 1–70. doi:10.5194/egusphere-2023-1753. https://egusphere.copernicus.org/preprints/2023/egusphere-2023-1753/.

- ↑ APRI (2024-11-11). "The justice and governance of solar geoengineering: Charting the path at COP29 and beyond" (in en-US). APRI. https://afripoli.org/the-justice-and-governance-of-solar-geoengineering-charting-the-path-at-cop29-and-beyond. "Across several major powers and international forums, the growing momentum in solar geoengineering technologies, assessments, and research and development is raising urgent ethical, justice and human and environmental rights issues that need to be addressed."

- ↑ Reynolds, Jesse L. (2019-09-27). "Solar geoengineering to reduce climate change: a review of governance proposals". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 475 (2229). doi:10.1098/rspa.2019.0255. PMID 31611719. Bibcode: 2019RSPSA.47590255R.

- ↑ "The Causes of Climate Change". NASA. https://climate.nasa.gov/causes.

- ↑ Hansson, Anders; Anshelm, Jonas; Fridahl, Mathias; Haikola, Simon (2021-04-29). "Boundary Work and Interpretations in the IPCC Review Process of the Role of Bioenergy With Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) in Limiting Global Warming to 1.5°C" (in en). Frontiers in Climate 3. doi:10.3389/fclim.2021.643224. Bibcode: 2021FrCli...3.3224H.

- ↑ Carton, Wim (2020-11-13). "3 Carbon Unicorns and Fossil Futures: Whose Emission Reduction Pathways is the IPCC Performing?" (in en). Has It Come to This?. pp. 34–49. doi:10.36019/9781978809390-003. ISBN 978-1-9788-0939-0.

- ↑ Emissions Gap Report 2024 (Report). UN environment programme. 2024-10-17. p. 32. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024. "As table 4.3 shows, a continuation of the current NDC scenarios would result in an increase in the emissions gap in 2035 of 4 GtCO2e for a 2°C warming limit, and 7 GtCO2e for a 1.5°C limit, whereas a continuation of the mitigation effort implied by current policies would lead to an even wider gap in 2035."

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering (2021-03-25) (in en). Reflecting Sunlight: Recommendations for Solar Geoengineering Research and Research Governance. doi:10.17226/25762. ISBN 978-0-309-67605-2. Bibcode: 2021nap..book25762N. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25762/reflecting-sunlight-recommendations-for-solar-geoengineering-research-and-research-governance. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ↑ President's Science Advisory Committee, Environmental Pollution Panel (Nov 1, 1965). Restoring the Quality of Our Environment. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/31937-document-2-white-house-report-restoring-quality-our-environment-report-environmental.

- ↑ "Geoengineering: A Short History". Foreign Policy. 2013. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/09/03/geoengineering-a-short-history/.

- ↑ Budyko, M. I. (1977) (in English). Climatic changes. Washington: American Geophysical Union. ISBN 978-0-87590-206-7.

- ↑ Budyko, M. I. (1977). "On present-day climatic changes" (in en). Tellus 29 (3): 193–204. doi:10.1111/j.2153-3490.1977.tb00725.x. Bibcode: 1977Tell...29..193B. http://tellusa.net/index.php/tellusa/article/view/11347.

- ↑ Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming: Mitigation, Adaptation, and the Science Base. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 1992-01-01. doi:10.17226/1605. ISBN 978-0-309-04386-1. Bibcode: 1992nap..book.1605I. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/1605. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ↑ Govindasamy, Bala; Caldeira, Ken (2000-07-15). "Geoengineering Earth's radiation balance to mitigate CO2-induced climate change" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 27 (14): 2141–2144. doi:10.1029/1999GL006086. ISSN 0094-8276. Bibcode: 2000GeoRL..27.2141G. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/1999GL006086.

- ↑ Keith, David W. (2000). "Geoengineering the Climate: History and Prospect" (in en). Annual Review of Energy and the Environment 25 (1): 245–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.245. ISSN 1056-3466. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.245.

- ↑ Crutzen, Paul J. (2006-07-25). "Albedo Enhancement by Stratospheric Sulfur Injections: A Contribution to Resolve a Policy Dilemma?" (in en). Climatic Change 77 (3): 211–220. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y. ISSN 1573-1480. Bibcode: 2006ClCh...77..211C.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Royal Society of London, ed (2009). Geoengineering the climate: Science, governance and uncertainty. London: Royal Society. ISBN 978-0-85403-773-5.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 National Research Council (10 February 2015). Climate Intervention: Reflecting Sunlight to Cool Earth. The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-31482-4. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18988/climate-intervention-reflecting-sunlight-to-cool-earth. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 UNESCO World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (2023). "Report of the World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST) on the ethics of climate engineering". https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386677.

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 28.12 28.13 28.14 28.15 28.16 28.17 28.18 28.19 28.20 28.21 28.22 28.23 28.24 28.25 28.26 28.27 28.28 28.29 Scientific Advice Mechanism to the European Commission (2024-12-09) (in en). Solar radiation modification: evidence review report (Report). SAPEA. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14283096. https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.14283096.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation and Group of Chief Scientific Advisors (2024). Solar radiation modification. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2777/391614. ISBN 978-92-68-19568-0. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/391614.

- ↑ Storelvmo, T.; Herger, N. (2014). "Cirrus cloud seeding has potential to cool climate". Geophysical Research Letters 41 (20). doi:10.1002/2014GL061652.

- ↑ Smith, Wake (2020). "The cost of stratospheric aerosol injection through 2100". Environmental Research Letters 15 (11): 114004. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aba7e7. Bibcode: 2020ERL....15k4004S.

- ↑ Proctor, Jonathan; Hsiang, Solomon; Burney, Jennifer; Burke, Marshall; Schlenker, Wolfram (August 2018). "Estimating global agricultural effects of geoengineering using volcanic eruptions". Nature 560 (7719): 480–483. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0417-3. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 30089909. Bibcode: 2018Natur.560..480P.

- ↑ Clark, Brendan; Robock, Alan; Xia, Lili; Rabin, Sam S.; Guarin, Jose R.; Hoogenboom, Gerrit; Jägermeyr, Jonas (February 2025). "Maize Yield Changes Under Sulfate Aerosol Climate Intervention Using Three Global Gridded Crop Models" (in en). Earth's Future 13 (2). doi:10.1029/2024EF005269. ISSN 2328-4277. Bibcode: 2025EaFut..1305269C.

- ↑ Birnbaum, Michael (February 27, 2023). "A 'climate solution' that spies worry could trigger war". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/02/27/geoengineering-security-war/.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Ricke, Katharine; Wan, Jessica S.; Saenger, Marissa; Lutsko, Nicholas J. (2023-05-31). "Hydrological Consequences of Solar Geoengineering" (in en). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 51 (1): 447–470. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-031920-083456. ISSN 0084-6597. Bibcode: 2023AREPS..51..447R.

- ↑ Erlick, Carynelisa; Frederick, John E (1998). "Effects of aerosols on the wavelength dependence of atmospheric transmission in the ultraviolet and visible 2. Continental and urban aerosols in clear skies". J. Geophys. Res. 103 (D18): 23275–23285. doi:10.1029/98JD02119. Bibcode: 1998JGR...10323275E.

- ↑ Kravitz, Ben; MacMartin, Douglas G. (13 January 2020). "Uncertainty and the basis for confidence in solar geoengineering research" (in en). Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (1): 64–75. doi:10.1038/s43017-019-0004-7. ISSN 2662-138X. Bibcode: 2020NRvEE...1...64K. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43017-019-0004-7. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Hansen, James E.; Kharecha, Pushker; Sato, Makiko; Tselioudis, George; Kelly, Joseph; Bauer, Susanne E.; Ruedy, Reto (2025). "Global Warming Has Accelerated: Are the United Nations and the Public Well-Informed?" (in en). Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 67 (1): 6–44. doi:10.1080/00139157.2025.2434494. Bibcode: 2025ESPSD..67....6H. 50x50px Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ↑ Mann, Michael E. (2021). The new climate war: the fight to take back our planet (First ed.). Melbourne London: Scribe Publications. ISBN 978-1-5417-5823-0.

- ↑ Parson, Edward A.; Keith, David W. (2024-10-18). "Solar Geoengineering: History, Methods, Governance, Prospects" (in en). Annual Review of Environment and Resources 49 (1): 337–366. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-112321-081911. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ↑ Reynolds, Jesse L. (2019-05-23). The Governance of Solar Geoengineering: Managing Climate Change in the Anthropocene (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316676790. ISBN 978-1-316-67679-0. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781316676790/type/book.

- ↑ Nielsen, Jeffrey (2025-01-10). "The big green button: stratospheric aerosol injection as a geopolitical dilemma during strategic competition between the United States and China, and implications for expanding aerosol injection near-term research" (in en). Oxford Open Climate Change 5 (1). doi:10.1093/oxfclm/kgaf009. ISSN 2634-4068. https://academic.oup.com/oocc/article/doi/10.1093/oxfclm/kgaf009/8042357.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Biermann, Frank; Oomen, Jeroen; Gupta, Aarti; Ali, Saleem H.; Conca, Ken; Hajer, Maarten A.; Kashwan, Prakash; Kotzé, Louis J. et al. (May 2022). "Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non-use agreement" (in en). WIREs Climate Change 13 (3). doi:10.1002/wcc.754. ISSN 1757-7780. Bibcode: 2022WIRCC..13E.754B. https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.754.

- ↑ Victor, David G. (2008). "On the regulation of geoengineering". Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24 (2): 322–336. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn018.

- ↑ Parson, Edward A. (April 2014). "Climate Engineering in Global Climate Governance: Implications for Participation and Linkage" (in en). Transnational Environmental Law 3 (1): 89–110. doi:10.1017/S2047102513000496. ISSN 2047-1025. Bibcode: 2014TELaw...3...89P. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2047102513000496/type/journal_article.

- ↑ Parker, Andy; Irvine, Peter J. (March 2018). "The Risk of Termination Shock From Solar Geoengineering" (in en). Earth's Future 6 (3): 456–467. doi:10.1002/2017EF000735. Bibcode: 2018EaFut...6..456P.

- ↑ Rabitz, Florian (2019-04-16). "Governing the termination problem in solar radiation management" (in en). Environmental Politics 28 (3): 502–522. doi:10.1080/09644016.2018.1519879. ISSN 0964-4016. Bibcode: 2019EnvPo..28..502R. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2018.1519879. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ↑ International Law Commission (2021). Draft guidelines on the protection of the atmosphere. United Nations. https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/8_8_2021.pdf.

- ↑ Geoengineering in relation to the Convention on Biological Diversity. CBD technical series. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2012. ISBN 978-92-9225-429-2.

- ↑ Convention on Biological Diversity, Conference of the Parties to the (8 December 2016). Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, XIII/14. Climate-related Geoengineering. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-13/cop-13-dec-14-en.pdf.

- ↑ Temple, James (January 20, 2023). "What Mexico's planned geoengineering restrictions mean for the future of the field". MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/01/20/1067146/what-mexicos-planned-geoengineering-restrictions-mean-for-the-future-of-the-field/.

- ↑ Jacob, Manon (February 27, 2025). "Proposed 'weather control' bans surge across US states". AFP. https://uk.news.yahoo.com/proposed-weather-control-bans-surge-011847281.html.

- ↑ Rayner, Steve; Heyward, Clare; Kruger, Tim; Pidgeon, Nick; Redgwell, Catherine; Savulescu, Julian (December 2013). "The Oxford Principles" (in en). Climatic Change 121 (3): 499–512. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-0675-2. ISSN 0165-0009. Bibcode: 2013ClCh..121..499R. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10584-012-0675-2.

- ↑ Vasquez, Krystal (October 24, 2024). "AGU publishes ethical framework for geoengineering". Chemical & Engineering News. https://cen.acs.org/environment/climate-change/AGU-publishes-ethical-framework-geoengineering/102/i34.

- ↑ Union, American Geophysical (2024-10-17), Ethical Framework Principles for Climate Intervention Research, doi:10.22541/essoar.172917365.53105072/v1, https://essopenarchive.org/users/270408/articles/1233540, retrieved 2025-03-22

- ↑ James Temple (18 April 2017). "The Growing Case for Geoengineering". MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2017/04/18/152336/the-growing-case-for-geoengineering/.

- ↑ "Fuel to the Fire: How Geoengineering Threatens to Entrench Fossil Fuels and Accelerate the Climate Crisis (Feb 2019)" (in en-US). https://www.ciel.org/reports/fuel-to-the-fire-how-geoengineering-threatens-to-entrench-fossil-fuels-and-accelerate-the-climate-crisis-feb-2019/.

- ↑ Hamilton, Clive (2015-02-12). "Opinion | The Risks of Climate Engineering" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/12/opinion/the-risks-of-climate-engineering.html.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 ((SRM360 Team)) (May 14, 2025). "SRM Funding Overview". SRM360. https://srm360.org/article/srm-funding-overview/.

- ↑ "An open letter regarding research on reflecting sunlight to reduce the risks of climate change" (in en-US). https://climate-intervention-research-letter.org/.

- ↑ "Home - call-for-balance.com" (in en). https://www.call-for-balance.com/.

- ↑ "Climate Change: Have We Lost the Battle?". November 2009. https://www.imeche.org/policy-and-press/reports/detail/climate-change-have-we-lost-the-battle.

- ↑ "Give research into solar geoengineering a chance" (in en). Nature 593 (7858): 167. 2021-05-12. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01243-0. PMID 33981056. Bibcode: 2021Natur.593..167..

- ↑ Reekie, Tristan; Howard, Will (April 2012). "Geoengineering". https://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/sites/default/files/47019_Chief-Scientist-_OccassionalPaperSeries_lores.pdf.

- ↑ Brom, F. (2013). Riphagen, M. ed. Klimaatengineering: hype, hoop of wanhoop?. Rathenau Instituut. ISBN 978-90-77364-51-2. https://www.rathenau.nl/nl/kennis-voor-transities/klimaatengineering.

- ↑ "Position statement on climate intervention" (in en). January 2018. https://www.agu.org/share-and-advocate/share/policymakers/position-statements/climate-intervention-requirements.

- ↑ (in en) Climate Science Special Report (Report). U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC. 2017. pp. 1–470. https://science2017.globalchange.gov/chapter/executive-summary/.

- ↑ "Reflecting Sunlight to Reduce Climate Risk: Priorities for Research and International Cooperation" (in en). April 2022. https://www.cfr.org/report/reflecting-sunlight-reduce-climate-risk.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Research to Inform Decisions about Climate Intervention". December 2024. https://www.wcrp-climate.org/ci-overview.

- ↑ "UK government's view on greenhouse gas removal technologies and solar radiation management" (in en). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/geo-engineering-research-the-government-s-view/uk-governments-view-on-greenhouse-gas-removal-technologies-and-solar-radiation-management.

- ↑ Canada, Environment and Climate Change (2024-02-16). "Environment and Climate Change Canada Science Strategy 2024 to 2029". https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/science-technology/science-strategy/2024-2029.html.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Bundesumweltministeriums (2023-12-06). "Klimaaußenpolitik-Strategie der Bundesregierung (KAP)- BMUV - Download" (in de). https://www.bmuv.de/DL3205.

- ↑ Hunt, Hugh; Fitzgerald, Shaun (2025-02-17). "Geoengineering is politically off-limits – could a Trump presidency change that?" (in en-US). https://theconversation.com/geoengineering-is-politically-off-limits-could-a-trump-presidency-change-that-248589.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "About". https://www.degrees.ngo/about/.

- ↑ Chalmin, Anja. "Global Southwashing: How The Degrees Initiative is imposing its solar geoengineering agenda onto climate research in the Global South - Geoengineering Monitor" (in en-US). https://www.geoengineeringmonitor.org/the-degrees-initiative.

- ↑ https://www.operaatioarktis.fi/

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "About" (in en-US). https://www.silverlining.ngo/about.

- ↑ "SilverLining Announces $20.5 Million in Funding to Advance its Governance and Equity Initiatives on Near-Term Climate Risk and Climate Intervention" (in en-US). https://www.silverlining.ngo/insights/silverlining-announces-20-5-million-in-funding.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Temple, James (14 June 2024). "This London nonprofit is now one of the biggest backers of geoengineering research" (in en). https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/06/14/1093778/foundations-are-lining-up-to-fund-geoengineering-research/.

- ↑ "About" (in en-US). https://sgdeliberation.org/about/.

- ↑ "C2G Mission" (in en-US). https://www.c2g2.net/c2g-mission/.

- ↑ "Commission" (in en). https://www.overshootcommission.org/commissioners.

- ↑ "Reducing the Risks of Climate Overshoot" (in en). 2023. https://www.overshootcommission.org/report.

- ↑ "Homepage" (in en-US). https://srm360.org/.

- ↑ "Governance and Funding" (in en-US). https://srm360.org/funding/.

- ↑ "LAD Climate Fund: Clear-Eyed, Comprehensive Climate Strategy" (in en-US). https://lad-climate.org/.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 "About" (in en). https://reflective.org/about/.

- ↑ "Funding for Solar Geoengineering from 2008 to 2018" (in en). 13 November 2018. https://geoengineering.environment.harvard.edu/blog/funding-solar-geoengineering.

- ↑ Temple, James (July 1, 2022). "The US government is developing a solar geoengineering research plan". MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/07/01/1055324/the-us-government-is-developing-a-solar-geoengineering-research-plan/.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Carrington, Damian (22 Apr 2025). "UK scientists to launch outdoor geoengineering experiments". https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/apr/22/uk-scientists-outdoor-geoengineering-experiments.

- ↑ Flavelle, Christopher; Gelles, David (2024-09-13). "U.K. to Fund 'Small-Scale' Outdoor Geoengineering Tests" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/13/climate/united-kingdom-geoengineering-research.html.

- ↑ "Exploring Climate Cooling". https://www.aria.org.uk/opportunity-spaces/future-proofing-our-climate-and-weather/exploring-climate-cooling.

- ↑ "Modelling the impact of solar radiation modification". 3 Apr 2025. https://www.ukri.org/news/modelling-the-impact-of-solar-radiation-modification/.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "Silicon Valley's Elite Pour Money Into Blotting Out the Sun" (in en). Bloomberg.com. 2024-10-25. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-10-25/silicon-valley-s-elite-back-controversial-research-into-blocking-the-sun?srnd=homepage-europe.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Flavelle, Christopher (2024-09-26). "Conspiracy Theorists and Vaccine Skeptics Have a New Target: Geoengineering" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/26/climate/geoengineering-conspiracy-theorists-skeptics.html.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 "Proposed 'weather control' bans surge across US states" (in en). 2025-02-27. https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250227-proposed-weather-control-bans-surge-across-us-states.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 Maruf, Ramishah; Miller, Brandon (2025-03-25). "State lawmakers are looking to ban non-existent 'chemtrails.' It could have real-life side effects." (in en). https://edition.cnn.com/2025/03/25/climate/state-bills-chemtrails-geoengineering-ban/index.html.

- ↑ Putman, Ceri (2025-04-01). "A Growing Number of US States Consider Bills to Ban Geoengineering" (in en-US). SRM360. https://srm360.org/perspective/us-states-consider-bills-to-ban-geoengineering/.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "CAN Position: Solar Radiation Modification (SRM), September 2019" (in en-GB). https://climatenetwork.org/resource/can-position-solar-radiation-modification-srm-september-2019/.

- ↑ "Climate & Geoengineering | ETC Group" (in en). https://www.etcgroup.org/issues/climate-geoengineering.

- ↑ "Geoengineering | Heinrich Böll Stiftung" (in en). https://www.boell.de/en/tags/geoengineering.

- ↑ "Geoengineering" (in en-US). https://www.ciel.org/issue/geoengineering/.

- ↑ Dunleavy, Haley (2021-07-07). "An Indigenous Group's Objection to Geoengineering Spurs a Debate About Social Justice in Climate Science" (in en-US). https://insideclimatenews.org/news/07072021/sami-sweden-objection-geoengineering-justice-climate-science/.

- ↑ "Open letter requesting cancellation of plans for geoengineering related test flights in Kiruna" (in no-NO). 2 March 2021. https://www.saamicouncil.net/news-archive/open-letter-requesting-cancellation-of-plans-for-geoengineering.

- ↑ "Signatories" (in en-US). https://www.solargeoeng.org/non-use-agreement/signatories/.

- ↑ "Endorsements" (in en-US). https://www.solargeoeng.org/non-use-agreement/endorsements/.

- ↑ Solar Geoengineering Non-Use Agreement (2022). "Press Release - Global coalition of leading scientists calls for International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering". https://www.solargeoeng.org/wp-content/library/downloads/EN_SolarGeoeng_PressRelease_220116.pdf.

- ↑ Solar Geoengineering Non-Use Agreement. "Funding Transparency". https://www.solargeoeng.org/funding-transparency/.

- ↑ "Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non-use agreement by Biermann et al. (DOI: 10.1002/wcc.754)" (in en). WIREs Climate Change 14 (5). September 2023. doi:10.1002/wcc.835. ISSN 1757-7780. Bibcode: 2023WIRCC..14E.835.. https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.835.

- ↑ Parson, Edward A.; Buck, Holly J.; Jinnah, Sikina; Moreno-Cruz, Juan; Nicholson, Simon (September 2024). "Toward an evidence-informed, responsible, and inclusive debate on solar geoengineering: A response to the proposed non-use agreement" (in en). WIREs Climate Change 15 (5). doi:10.1002/wcc.903. ISSN 1757-7780. Bibcode: 2024WIRCC..15E.903P. https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.903.

- ↑ White, Rebekah (3 April 2025). "Failure to Communicate". Science 388 (6742): 20–24. doi:10.1126/science.z0g6jc4. PMID 40179177. https://www.science.org/content/article/geoengineering-fight-climate-change-if-public-can-convinced.

- ↑ LegiScan. "Roll Call: TN SB2691 | 2023-2024 | 113th General Assembly". https://legiscan.com/TN/rollcall/SB2691/id/1418530.

- ↑ Putman, Ceri (2025-04-01). "A Growing Number of US States Consider Bills to Ban Geoengineering" (in en-US). SRM360. https://srm360.org/news-reaction/us-states-consider-bills-to-ban-geoengineering/.

- ↑ Talcott, Anthony (2025-06-30). "Florida weather-control ban takes effect this week. Here's what that means" (in en). https://www.clickorlando.com/news/politics/2025/06/30/florida-weather-control-ban-takes-effect-this-week-heres-what-that-means/.

- ↑ Fields, Ashleigh (July 5, 2025). "Greene to introduce 'weather modification' bill". The Hill. https://thehill.com/homenews/house/5386499-greene-to-introduce-weather-modification-bill/.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 United States Environmental Protection Agency (15 April 2025). "EPA Demands Answers from Unregulated Geoengineering Start-Up Launching Sulfur Dioxide into the Air" (in en). https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-demands-answers-unregulated-geoengineering-start-launching-sulfur-dioxide-air.

- ↑ "Make Sunsets". https://makesunsets.com/.

- ↑ Simon, Julia (April 21, 2024). "Startups want to cool Earth by reflecting sunlight. There are few rules and big risks". https://www.npr.org/2024/04/21/1244357506/earth-day-solar-geoengineering-climate-make-sunsets-stardust.

- ↑ Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos, Gobierno de México. "La experimentación con geoingeniería solar no será permitida en México" (in es). https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/prensa/la-experimentacion-con-geoingenieria-solar-no-sera-permitida-en-mexico?idiom=es.

- ↑ de la Garza, Alejandro (February 21, 2023). "Exclusive: Inside a Controversial Startup's Risky Attempt to Control Our Climate". https://time.com/6257102/geoengineering-make-sunsets-us-balloon-launch-exclusive/. ""'Skeptics of solar geoengineering experimentation as well as proponents are rarely unified,' says Kevin Surprise, a lecturer on environmental studies at Mount Holyoke College. "I have not seen a single person in the field say this is a good idea.'""

Note: This topic belongs to "Climate change" portalTemplate:Climate change

|