Earth:Water resources

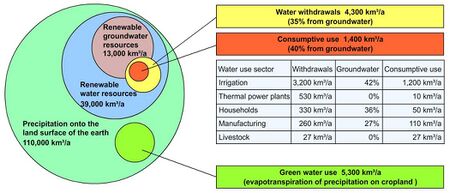

Water resourcesare natural resources of water that are potentially useful for humans,[1] for example as a source of drinking water supply or irrigation water. 97% of the water on Earth is salt water and only three percent is fresh water; slightly over two-thirds of this is frozen in glaciers and polar ice caps.[2] The remaining unfrozen freshwater is found mainly as groundwater, with only a small fraction present above ground or in the air.[3] Natural sources of fresh water include surface water, under river flow, groundwater and frozen water. Artificial sources of fresh water can include treated wastewater (wastewater reuse) and desalinated seawater. Human uses of water resources include agricultural, industrial, household, recreational and environmental activities.

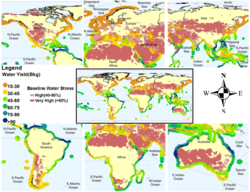

Water resources are under threat from water scarcity, water pollution, water conflict and climate change. Fresh water is a renewable resource, yet the world's supply of groundwater is steadily decreasing, with depletion occurring most prominently in Asia, South America and North America, although it is still unclear how much natural renewal balances this usage, and whether ecosystems are threatened.[4]

Natural sources of fresh water

Natural sources of fresh water include surface water, under river flow, groundwater and frozen water.

Surface water

Surface water is water in a river, lake or fresh water wetland. Surface water is naturally replenished by precipitation and naturally lost through discharge to the oceans, evaporation, evapotranspiration and groundwater recharge. The only natural input to any surface water system is precipitation within its watershed. The total quantity of water in that system at any given time is also dependent on many other factors. These factors include storage capacity in lakes, wetlands and artificial reservoirs, the permeability of the soil beneath these storage bodies, the runoff characteristics of the land in the watershed, the timing of the precipitation and local evaporation rates. All of these factors also affect the proportions of water loss.

Humans often increase storage capacity by constructing reservoirs and decrease it by draining wetlands. Humans often increase runoff quantities and velocities by paving areas and channelizing the stream flow.

Natural surface water can be augmented by importing surface water from another watershed through a canal or pipeline.

Brazil is estimated to have the largest supply of fresh water in the world, followed by Russia and Canada .[5]

-

Panorama of a natural wetland (Sinclair Wetlands, New Zealand)

Water from glaciers

Glacier runoff is considered to be surface water. The Himalayas, which are often called "The Roof of the World", contain some of the most extensive and rough high altitude areas on Earth as well as the greatest area of glaciers and permafrost outside of the poles. Ten of Asia's largest rivers flow from there, and more than a billion people's livelihoods depend on them. To complicate matters, temperatures there are rising more rapidly than the global average. In Nepal, the temperature has risen by 0.6 degrees Celsius over the last decade, whereas globally, the Earth has warmed approximately 0.7 degrees Celsius over the last hundred years.[6]

Groundwater

Under river flow

Throughout the course of a river, the total volume of water transported downstream will often be a combination of the visible free water flow together with a substantial contribution flowing through rocks and sediments that underlie the river and its floodplain called the hyporheic zone. For many rivers in large valleys, this unseen component of flow may greatly exceed the visible flow. The hyporheic zone often forms a dynamic interface between surface water and groundwater from aquifers, exchanging flow between rivers and aquifers that may be fully charged or depleted. This is especially significant in karst areas where pot-holes and underground rivers are common.

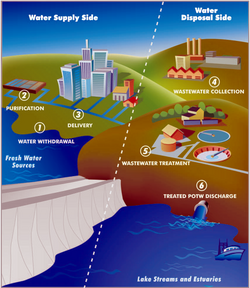

Artificial sources of usable water

Artificial sources of fresh water can include treated wastewater (reclaimed water), atmospheric water generators,[7][8][9] and desalinated seawater. However, the economic and environmental side effects of these technologies must also be taken into consideration.[10]

Wastewater reuse

Desalinated water

Research into other options

Air-capture over oceans

Researchers proposed "significantly increasing freshwater through the capture of humid air over oceans" to address present and, especially, future water scarcity/insecurity.[12][11]

Atmospheric water generators on land

A potentials-assessment study proposed hypothetical portable solar-powered atmospheric water harvesting devices which are under development, along with design criteria, finding they could help a billion people to access safe drinking water, albeit such off-the-grid generation may sometimes "undermine efforts to develop permanent piped infrastructure" among other problems.[13][14][15]

Water uses

The total quantity of water available at any given time is an important consideration. Some human water users have an intermittent need for water. For example, many farms require large quantities of water in the spring, and no water at all in the winter. To supply such a farm with water, a surface water system may require a large storage capacity to collect water throughout the year and release it in a short period of time. Other users have a continuous need for water, such as a power plant that requires water for cooling. To supply such a power plant with water, a surface water system only needs enough storage capacity to fill in when average stream flow is below the power plant's need. Nevertheless, over the long term the average rate of precipitation within a watershed is the upper bound for average consumption of natural surface water from that watershed.

Agriculture and other irrigation

Industries

It is estimated that 22% of worldwide water is used in industry.[16] Major industrial users include hydroelectric dams, thermoelectric power plants, which use water for cooling, ore and oil refineries, which use water in chemical processes, and manufacturing plants, which use water as a solvent. Water withdrawal can be very high for certain industries, but consumption is generally much lower than that of agriculture.

Water is used in renewable power generation. Hydroelectric power derives energy from the force of water flowing downhill, driving a turbine connected to a generator. This hydroelectricity is a low-cost, non-polluting, renewable energy source. Significantly, hydroelectric power can also be used for load following unlike most renewable energy sources which are intermittent. Ultimately, the energy in a hydroelectric power plant is supplied by the sun. Heat from the sun evaporates water, which condenses as rain in higher altitudes and flows downhill. Pumped-storage hydroelectric plants also exist, which use grid electricity to pump water uphill when demand is low, and use the stored water to produce electricity when demand is high.

Thermoelectric power plants using cooling towers have high consumption, nearly equal to their withdrawal, as most of the withdrawn water is evaporated as part of the cooling process. The withdrawal, however, is lower than in once-through cooling systems.

Water is also used in many large scale industrial processes, such as thermoelectric power production, oil refining, fertilizer production and other chemical plant use, and natural gas extraction from shale rock. Discharge of untreated water from industrial uses is pollution. Pollution includes discharged solutes and increased water temperature (thermal pollution).

Drinking water and domestic use (households)

It is estimated that 8% of worldwide water use is for domestic purposes.[16] These include drinking water, bathing, cooking, toilet flushing, cleaning, laundry and gardening. Basic domestic water requirements have been estimated by Peter Gleick at around 50 liters per person per day, excluding water for gardens.

Drinking water is water that is of sufficiently high quality so that it can be consumed or used without risk of immediate or long term harm. Such water is commonly called potable water. In most developed countries, the water supplied to domestic, commerce and industry is all of drinking water standard even though only a very small proportion is actually consumed or used in food preparation.

844 million people still lacked even a basic drinking water service in 2017.[17]: 3 Of those, 159 million people worldwide drink water directly from surface water sources, such as lakes and streams.[17]: 3 One in eight people in the world do not have access to safe water.[18][19]

Environment

Explicit environment water use is also a very small but growing percentage of total water use. Environmental water may include water stored in impoundments and released for environmental purposes (held environmental water), but more often is water retained in waterways through regulatory limits of abstraction.[20] Environmental water usage includes watering of natural or artificial wetlands, artificial lakes intended to create wildlife habitat, fish ladders, and water releases from reservoirs timed to help fish spawn, or to restore more natural flow regimes.[21]

Environmental usage is non-consumptive but may reduce the availability of water for other users at specific times and places. For example, water release from a reservoir to help fish spawn may not be available to farms upstream, and water retained in a river to maintain waterway health would not be available to water abstractors downstream.

Recreation

Recreational water use is mostly tied to lakes, dams, rivers or oceans. If a water reservoir is kept fuller than it would otherwise be for recreation, then the water retained could be categorized as recreational usage. Examples are anglers, water skiers, nature enthusiasts and swimmers.

Recreational usage is usually non-consumptive. However, recreational usage may reduce the availability of water for other users at specific times and places. For example, water retained in a reservoir to allow boating in the late summer is not available to farmers during the spring planting season. Water released for whitewater rafting may not be available for hydroelectric generation during the time of peak electrical demand.

Challenges and threats

Threats for the availability of water resources include: Water scarcity, water pollution, water conflict and climate change.

Water scarcity

Water pollution

Water conflict

Climate change

Water resource management

Water resource management is the activity of planning, developing, distributing and managing the optimum use of water resources. It is an aspect of water cycle management. The field of water resources management will have to continue to adapt to the current and future issues facing the allocation of water. With the growing uncertainties of global climate change and the long-term impacts of past management actions, this decision-making will be even more difficult. It is likely that ongoing climate change will lead to situations that have not been encountered. As a result, alternative management strategies, including participatory approaches and adaptive capacity are increasingly being used to strengthen water decision-making.

Ideally, water resource management planning has regard to all the competing demands for water and seeks to allocate water on an equitable basis to satisfy all uses and demands. As with other resource management, this is rarely possible in practice so decision-makers must prioritise issues of sustainability, equity and factor optimisation (in that order!) to achieve acceptable outcomes. One of the biggest concerns for water-based resources in the future is the sustainability of the current and future water resource allocation.

Sustainable Development Goal 6 has a target related to water resources management: "Target 6.5: By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate."[26][27]

Sustainable water management

At present, only about 0.08 percent of all the world's fresh water is accessible. And there is ever-increasing demand for drinking, manufacturing, leisure and agriculture. Due to the small percentage of water available, optimizing the fresh water we have left from natural resources has been a growing challenge around the world.

Much effort in water resource management is directed at optimizing the use of water and in minimizing the environmental impact of water use on the natural environment. The observation of water as an integral part of the ecosystem is based on integrated water resources management, based on the 1992 Dublin Principles (see below).

Sustainable water management requires a holistic approach based on the principles of Integrated Water Resource Management, originally articulated in 1992 at the Dublin (January) and Rio (July) conferences. The four Dublin Principles, promulgated in the Dublin Statement are:

- Fresh water is a finite and vulnerable resource, essential to sustain life, development and the environment;

- Water development and management should be based on a participatory approach, involving users, planners and policy-makers at all levels;

- Women play a central part in the provision, management and safeguarding of water;

- Water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good.

Implementation of these principles has guided reform of national water management law around the world since 1992.

Further challenges to sustainable and equitable water resources management include the fact that many water bodies are shared across boundaries which may be international (see water conflict) or intra-national (see Murray-Darling basin).

Integrated water resources management

Integrated water resources management (IWRM) has been defined by the Global Water Partnership (GWP) as "a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximize the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems".[28]

Some scholars say that IWRM is complementary to water security because water security is a goal or destination, whilst IWRM is the process necessary to achieve that goal.[29]

IWRM is a paradigm that emerged at international conferences in the late 1900s and early 2000s, although participatory water management institutions have existed for centuries.[24] Discussions on a holistic way of managing water resources began already in the 1950s leading up to the 1977 United Nations Water Conference.[30] The development of IWRM was particularly recommended in the final statement of the ministers at the International Conference on Water and the Environment in 1992, known as the Dublin Statement. This concept aims to promote changes in practices which are considered fundamental to improved water resource management. IWRM was a topic of the second World Water Forum, which was attended by a more varied group of stakeholders than the preceding conferences and contributed to the creation of the GWP.[24]

In the International Water Association definition, IWRM rests upon three principles that together act as the overall framework:[31]

- Social equity: ensuring equal access for all users (particularly marginalized and poorer user groups) to an adequate quantity and quality of water necessary to sustain human well-being.

- Economic efficiency: bringing the greatest benefit to the greatest number of users possible with the available financial and water resources.

- Ecological sustainability: requiring that aquatic ecosystems are acknowledged as users and that adequate allocation is made to sustain their natural functioning.

In 2002, the development of IWRM was discussed at the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg, which aimed to encourage the implementation of IWRM at a global level.[32] The third World Water Forum recommended IWRM and discussed information sharing, stakeholder participation, and gender and class dynamics.[24]

Operationally, IWRM approaches involve applying knowledge from various disciplines as well as the insights from diverse stakeholders to devise and implement efficient, equitable and sustainable solutions to water and development problems. As such, IWRM is a comprehensive, participatory planning and implementation tool for managing and developing water resources in a way that balances social and economic needs, and that ensures the protection of ecosystems for future generations. In addition, in light of contributing the achievement of Sustainable Development goals (SDGs),[33] IWRM has been evolving into more sustainable approach as it considers the Nexus approach, which is a cross-sectoral water resource management. The Nexus approach is based on the recognition that "water, energy and food are closely linked through global and local water, carbon and energy cycles or chains."

An IWRM approach aims at avoiding a fragmented approach of water resources management by considering the following aspects: Enabling environment, roles of Institutions, management Instruments. Some of the cross-cutting conditions that are also important to consider when implementing IWRM are: Political will and commitment, capacity development, adequate investment, financial stability and sustainable cost recovery, monitoring and evaluation. There is not one correct administrative model. The art of IWRM lies in selecting, adjusting and applying the right mix of these tools for a given situation. IWRM practices depend on context; at the operational level, the challenge is to translate the agreed principles into concrete action.

Managing water in urban settings

By country

Water resource management and governance is handled differently by different countries. For example, in the United States , the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and its partners monitor water resources, conduct research and inform the public about groundwater quality.[34] Water resources in specific countries are described below: Script error: No such module "World topic".

See also

- International trade and water

- List of sovereign states by freshwater withdrawal

- List of countries by total renewable water resources

- Socio-hydrology

- Virtual water

- Water resources law

- Water rights

- Water storage

References

- ↑ "water resource | Britannica" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/water-resource.

- ↑ "Earth's water distribution". United States Geological Survey. http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/waterdistribution.html.

- ↑ "Scientific Facts on Water: State of the Resource". GreenFacts Website. http://www.greenfacts.org/en/water-resources/index.htm#2.

- ↑ Gleeson, Tom; Wada, Yoshihide; Bierkens, Marc F. P.; van Beek, Ludovicus P. H. (9 August 2012). "Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint". Nature 488 (7410): 197–200. doi:10.1038/nature11295. PMID 22874965. Bibcode: 2012Natur.488..197G.

- ↑ "The World's Water 2006–2007 Tables, Pacific Institute". Worldwater.org. http://www.worldwater.org/data.html.

- ↑ Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

- ↑ Shafeian, Nafise; Ranjbar, A.A.; Gorji, Tahereh B. (June 2022). "Progress in atmospheric water generation systems: A review" (in en). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 161: 112325. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112325.

- ↑ Jarimi, Hasila; Powell, Richard; Riffat, Saffa (18 May 2020). "Review of sustainable methods for atmospheric water harvesting". International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 15 (2): 253–276. doi:10.1093/ijlct/ctz072.

- ↑ Raveesh, G.; Goyal, R.; Tyagi, S.K. (July 2021). "Advances in atmospheric water generation technologies". Energy Conversion and Management 239: 114226. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114226.

- ↑ van Vliet, Michelle T H; Jones, Edward R; Flörke, Martina; Franssen, Wietse H P; Hanasaki, Naota; Wada, Yoshihide; Yearsley, John R (2021-02-01). "Global water scarcity including surface water quality and expansions of clean water technologies". Environmental Research Letters 16 (2): 024020. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abbfc3. ISSN 1748-9326. Bibcode: 2021ERL....16b4020V.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Rahman, Afeefa; Kumar, Praveen; Dominguez, Francina (6 December 2022). "Increasing freshwater supply to sustainably address global water security at scale" (in en). Scientific Reports 12 (1): 20262. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-24314-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 36473864. Bibcode: 2022NatSR..1220262R.

- University press release: "Researchers propose new structures to harvest untapped source of freshwater" (in en). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign via techxplore.com. https://techxplore.com/news/2022-12-harvest-untapped-source-freshwater.html.

- ↑ McDonald, Bob. "Water, water, everywhere — and maybe here's how to make it drinkable". https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/water-water-everywhere-and-maybe-here-s-how-to-make-it-drinkable-1.6703854.

- ↑ Yirka, Bob. "Model suggests a billion people could get safe drinking water from hypothetical harvesting device" (in en). Tech Xplore. https://techxplore.com/news/2021-10-billion-people-safe-hypothetical-harvesting.html.

- ↑ "Solar-powered harvesters could produce clean water for one billion people". Physics World. 13 November 2021. https://physicsworld.com/a/solar-powered-harvesters-could-produce-clean-water-for-one-billion-people/.

- ↑ Lord, Jackson; Thomas, Ashley; Treat, Neil; Forkin, Matthew; Bain, Robert; Dulac, Pierre; Behroozi, Cyrus H.; Mamutov, Tilek et al. (October 2021). "Global potential for harvesting drinking water from air using solar energy" (in en). Nature 598 (7882): 611–617. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03900-w. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 34707305. Bibcode: 2021Natur.598..611L.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "WBCSD Water Facts & Trends". http://www.wbcsd.org/includes/getTarget.asp?type=d&id=MTYyNTA.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 WHO, UNICEF (2017). Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene : 2017 update and SDG baselines.. Geneva. ISBN 978-9241512893. OCLC 1010983346. https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/resources-and-publications/library/details/2805.

- ↑ "Global WASH Fast Facts | Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | Healthy Water | CDC" (in en-us). 2018-11-09. https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/global/wash_statistics.html.

- ↑ Water Aid. "Water". http://www.wateraid.org/uk/what_we_do/the_need/5899.asp?gclid=CMvwnO7B164CFUcRfAodFkdffg.

- ↑ National Water Commission (2010). Australian environmental water management report. NWC, Canberra

- ↑ "Aral Sea trickles back to life". Silk Road Intelligencer. http://silkroadintelligencer.com/2010/07/27/aral-sea-trickles-back-to-life/.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:15 - ↑ 23.0 23.1 Caretta, M.A., A. Mukherji, M. Arfanuzzaman, R.A. Betts, A. Gelfan, Y. Hirabayashi, T.K. Lissner, J. Liu, E. Lopez Gunn, R. Morgan, S. Mwanga, and S. Supratid, 2022: Chapter 4: Water. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 551–712, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.006.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Rijsberman, Frank R. (2006). "Water scarcity: Fact or fiction?" (in en). Agricultural Water Management 80 (1–3): 5–22. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2005.07.001. Bibcode: 2006AgWM...80....5R. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378377405002854. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":0" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ IWMI (2007) Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. London: Earthscan, and Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

- ↑ Ritchie, Roser, Mispy, Ortiz-Ospina (2018) "Measuring progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals." (SDG 6) SDG-Tracker.org, website

- ↑ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ↑ "International Decade for Action 'Water for Life' 2005-2015. Focus Areas: Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)" (in EN). https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/iwrm.shtml#:~:text=It%20states:%20%27IWRM%20is%20a,the%20sustainability%20of%20vital%20ecosystems..

- ↑ Sadoff, Claudia; Grey, David; Borgomeo, Edoardo (2020). "Water Security". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.609. ISBN 978-0-19-938941-4.

- ↑ Asit K.B. (2004). Integrated Water Resources Management: A Reassessment, Water International, 29(2), 251

- ↑ "Integrated Water Resources Management: Basic Concepts | IWA Publishing". https://www.iwapublishing.com/news/integrated-water-resources-management-basic-concepts.

- ↑ Ibisch, Ralf B.; Bogardi, Janos J.; Borchardt, Dietrich (2016), Borchardt, Dietrich; Bogardi, Janos J.; Ibisch, Ralf B., eds. (in en), Integrated Water Resources Management: Concept, Research and Implementation, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3–32, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25071-7_1, ISBN 978-3-319-25069-4, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-25071-7_1, retrieved 2020-11-14

- ↑ Hülsmann, Stephan, ed (2018) (in en). Managing Water, Soil and Waste Resources to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75163-4. ISBN 978-3-319-75162-7. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-75163-4.

- ↑ "Water Resources" (in en). https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources.

External links

- Renewable water resources in the world by country

- Portal to international hydrology and water resources

- Cap-Net, Network for Capacity Building in Sustainable Water Management

- CKnet-INA, Indonesian Integrated Water Resource Management Secretariat

- Sustainable Sanitation and Water Management Toolbox

|