Engineering:Zero-carbon city

A zero-carbon city is a goal of city planners[1] that describes a significant reduction in carbon use by a city. The term describes a range of carbon reduction, ranging from a city that generates as much or more carbon-free sustainable energy as it uses,[2] to a city that manages greenhouse gas emissions and reduces its carbon footprint to a minimum (ideally 0 or negative) by using renewable energy sources, by reducing carbon emissions through efficient urban design, technology use and lifestyle changes, and balancing any remaining emissions through carbon sequestration.[3][4][5] Since the supply chains of a city stretch far beyond its borders, Princeton University's High Meadows Environmental Institute suggests using a transboundary definition of a net-zero carbon city as "one that has net-zero carbon infrastructure and food provisioning systems".[6]

Most cities throughout the world burn coal, oil or gas as a source of energy, resulting in the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, a key greenhouse gas. The development of cities is therefore intimately linked to the causes and impacts of climate change.[3][7] As of 2019[update], cities accounted for two thirds of all energy consumption and generated 70% of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.[8][9][10] Over 50% of the people in the world currently live in cities, a proportion that is projected to rise to 70% by 2050, and almost 80% by 2080.[4]

Urban development focused on lowering carbon is seen as an inevitable trend for sustainability in urban spaces.[7][11][12] Underlying goals include avoiding harm to the planet and countering the impacts of climate change.[4] As of 2022[update], over 1000 cities worldwide have undertaken steps to transition in response to climate change as part of the Cities Race to Zero campaign,[13] one part of a larger United Nations Race to Zero campaign.[14] Among them are cities including Rio de Janeiro, New York, Paris, Oslo, Mexico City, Melbourne, London, Milan, Cape Town, Buenos Aires, Caracas, Copenhagen, Vancouver[15] and Hong Kong.[16] In the United States, more than 100 cities have pledged to become carbon neutral.[17]

An established modern city attempting to achieve net-zero status needs to assess seven key provisioning systems, for energy, transportation-communications, food, construction materials, water, green infrastructure, and waste-management.[6][18][1] Strategies for reaching net zero include developing renewable energy supplies, reducing energy and resource use through better urban design and lifestyle changes, reducing waste, and creating green spaces and carbon sinks to remove carbon from the atmosphere.[3][7] Approaches to sustainable urban planning of zero carbon cities increasingly emphasize the use of locally sourced food, energy, and renewable resources.[19]

Some city planners have designed zero-carbon cities from scratch, instead of using and adapting established cities. This gives city planners greater control over all aspects of city design and how each city can contribute to being without carbon emissions. Such design enables the city to benefit from economies of scale and from construction options that might not be feasible in a city with existing structures. Such zero-carbon cities maintain optimal living conditions and economic development while eliminating environmental impact.[11]

Guiding principles

Net zero is a scientific concept that can be defined in terms of measurable targets. It can provide a frame of reference for understanding and assessing the impact of actions to address climate change. To be used as a framework for climate action, it must be operationalised and measured as part of the ongoing activities of social, political and economic systems.[20][5][21]

Time scale is an essential factor driving the urgency of net zero interventions. The impact of carbon emissions on surface warming of the planet is monotonic, near-linear (as of 2021) and long term. Attempts to achieve net zero must therefore be long term plans, maintained over multiple decades. The goal of net zero is to achieve a state of balance that can be maintained over multiple decades to centuries.[20]

Scientists can measure ongoing changes in the global atmosphere and estimate carbon budgets, but identifying and operationalising interventions occurs at multiple levels worldwide. As a frame of reference for decision-makers, global impact must be translated into definable targets for entities at national, subnational, corporate, organizational and individual levels.[20]

In practice, determination of net-zero targets has been self-regulated and voluntary. Entitles set and achieve goals, some participating in voluntary campaigns and initiatives such as the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Race to Zero campaign, Cities Race to Zero, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance, and the Science Based Targets initiative. Regular global progress assessments, including those of independent global initiatives such as CDP and the Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI), provide a form of feedback.[20] As of 2022[update], over 1000 cities,[13][22] including 25 megacities worldwide[15] and 100 cities in the United States, are part of Cities Race to Zero.[17]

While the setting of targets is key, it must be followed up through effective mechanisms for governance, monitoring, accountability and reporting. Long-term goals must be translated into practical near-term actions, with detailed plans and methods for establishing baselines, measuring outcomes and assessing impacts.[20][21] In many ways, cities are in a critical position to address climate issues effectively: they are large enough to benefit from economies of scale, and close enough to actual problems to focus on developing real implementable strategies. As demands on their infrastructures increase, they have a strong incentive to address issues and find and share solutions.[10]

Seven aspects of net zero have been identified as highly important to its successful use as a framework for climate action. These have relevance to the development of net zero cities.[20]

- Sooner is better. Front-loading climate action, combined with long-term planning over years or decades, is the most cost-effective way to reach temperature targets, as well as the most flexible in the face of new information.[20]

- Be comprehensive. Plans that tackle comprehensive rather than partial emissions reductions are becoming necessary as carbon levels reach critical tipping points. Harder-to-treat problem areas must be addressed as well as easier ones.[20]

- Beware of over-reliance on early-stage carbon removal strategies. These are not yet well understood and may enable a "business as usual" attitude to climate change.[20]

- Reassess and improve systems for carbon offsets. Such systems have been questioned in terms of their scientific and technical capabilities; environmental integrity; monitoring, reporting and verification structures; and social and environmental impact.[20]

- Apply principles of sustainable development. Achieving net zero globally requires implementation of equitable and just transitions that balance social, economic and environmental objectives in areas with very different conditions.[20]

- Focus on broad strategies for sustainability. Cities can potentially address multiple problems at once, through solutions that are nature-based, biodiversity-based and people-led.[20] It is important to consider that parents with small children, the poor, the elderly and the disabled may experience a city differently from those who are affluent and more easily mobile.[23]

- See opportunities. New net-zero solutions and innovation will drive economic shifts which will include opportunities for investment, renewal and growth.[20][21][24]

There are strong similarities between zero carbon cities and eco-cities. Discussions of eco-cities tend to focus more broadly on social and environmental issues, with less emphasis on carbon monitoring and the necessity of reaching net zero energy balance.[19] Many of the principles proposed for developing eco-cities are also relevant to net zero cities, including revising land use priorities to create sustainable mixed-use communities; revising transportation priorities to favor foot, bicycle, cart and public transit over automobiles; increasing environmental awareness; supporting local agriculture and community gardens; and promoting recycling and resource conservation.[25]

City infrastructure

| |

Urban areas involve essential infrastructure for energy, transport, water, food, shelter, construction, public spaces, and waste management. Transforming cities to achieve net zero sustainability means rethinking both supply-side issues (power supplies and transportation) and demand-side issues (reducing use through better urban design and policy.)[3][7] Key factors in city planning include density, land use mix, connectivity, and accessibility.[7]

To achieve net zero, a city must collectively reduce emissions of greenhouse gases to zero and cease all practices that emit greenhouse gases. Achieving net zero sustainability also means considering sources and production of materials, and ensuring that what comes into the city travels via zero-emission transport.[11][19] Appearing to reduce emissions in one location by shifting emissions-causing activities to a different location will not contribute to the global goal of a sustainable net zero environment.[26]

Energy

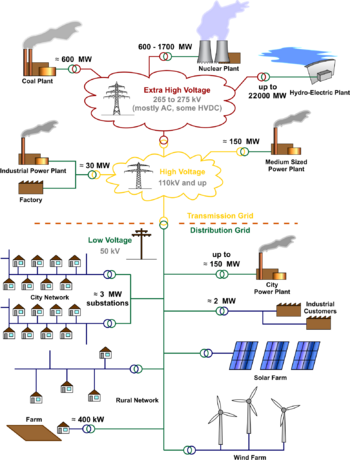

To become a zero-carbon city, renewable energy must supersede other non-renewable energy sources and become the sole source of energy, so a zero-carbon city is a renewable-energy-economy city. Transitioning to a zero carbon city means examining the generation of power sources, such as renewable electricity and decarbonising electricity production.[11][19]

Electricity needs are increasingly being met through the development of solar and wind power as energy sources, which are becoming the cheapest forms of power. The shift to solar power, in particular, means that energy can be produced close to its intended use. This is suited to a distributed energy infrastructure in which local areas are connected into a city-wide or region-wide electrical grid. The ability to provide a steady supply of electricity is also being supported by the development of more efficient and cost-effective battery storage technology.[7]

Issues of equity, balance, and efficiency are all relevant to energy distribution and use. A net-zero carbon electricity grid is a necessary foundation for supply side strategies that aim to shift provisioning systems for buildings, energy use, mobility, and light industrial energy use to electric power. The development of a net-zero carbon electric grid can become the basis for transitioning key urban activities such as transportation, heating, and cooking from fossil fuels to zero-carbon electricity.[7]

Transport

Transportation of people and goods is estimated to contribute 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[7] In terms of transport, approaches to low-carbon urban development often focus on reducing fossil-fuel based transportation, improving public transit, and creating areas of mixed use development so that people are more likely to work and shop near their homes, reducing transportation needs.[3] A study of 274 cities worldwide suggests that compact urban development is important in both affluent mature cities and developing-country cities with emerging infrastructures, reducing urban emissions by up to 25%.[27]

The transition from fossil-fuel-based cars and trucks to electric vehicles (EVs) is occurring globally. China has been a major center of technology growth for EVs. Vehicle-fuel technologies that can contribute to reductions in energy use include hybrid electric, plug-in electric, natural gas, and bioethanol-powered vehicles. The last diesel and gasoline cars are expected to be produced in the 2020s, with 25% or more of all vehicles worldwide being electric by 2040 as fossil fuel prices rise.[7]

A narrow focus on electrifying vehicles can lead planners to overlook opportunities for increasing efficiency within existing systems.[3] Good urban planning can develop an infrastructure that combines and supports initiatives in multiple areas. For example, the generation of solar power and the provision of recharge hubs near public transit can support the use of electric vehicles for both private and public transit.[7] Another way to support use of electric vehicles might be to integrate EV charging points into lampposts.[10]

Increasingly, city planners are looking to the use of digital technologies to create smarter and more sustainable cities.[28][29] By gathering large diverse datasets and modelling the impact of possible interventions, planners hope to identify and target key aspects of energy use, air quality, and traffic for improvement. By incorporating smart measurement technology into buildings, lighting, appliances and transportation, systems can better adapt to changing conditions, reduce energy consumption, and improve city services.[30][10]

Heating, cooling and cooking

Heating, cooling and cooking are also targets for improved energy efficiency and reduction of carbon emissions. Increasingly following Europe and Asia, North Americans are switching from gas or electrical resistance stoves to induction cooking.[31][32] Consumers are also switching heating systems from coal, fuel oil, or natural gas to electricity-driven steam or hot water; and to air-source or ground-source heat pumps for both heating and cooling.[7]

Food

Food production tends to be heavily dependent on fossil fuels, in the production of nitrogen fertilizer and to power agricultural machinery used in the planting, tending and harvesting of crops.[33][34] The movement of food from producers to consumers also tends to involve major fossil-fuel costs, since many crops are grown far from their potential market and have a short shelf life.[35] Many countries depend on international markets to obtain critical food supplies. Food production and supply chains are being increasingly destabilized by the effects of climate change on agriculture, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[36][37][38][39] In the United States, at the same time that millions of Americans experience food insecurity, as much as 40 percent of food is wasted.[40]

At the consumer level, steps towards achieving net zero include eating more local and plant-based foods, minimizing food waste, and composting remaining plant-based wastes. Consumers and investors may also choose to support companies based on their carbon footprint and transparency.[41][40][34]

In terms of city infrastructure, initiatives to identify and redirect usable food ("food rescue"),[42] to separate waste streams, and to improve handling of food waste are all important.[43][40][34] In low-income countries, small-scale and household-level biogas systems are being used to convert wastes into energy. Composting and anaerobic digestion (AD) are increasingly being used in countries at all income levels.[44][45]

Farmers and farming communities need scientific, technical, and financial support to move to more climate-friendly farming practices and to support initiatives for climate change adaptation, regenerative agriculture and biosequestration.[41][46][47][48] Collaboration between stakeholders at all levels of the private, public and civil sectors is needed to improve food sector infrastructure.[41][36]

Construction

The energy efficiency of buildings can be assessed and improved in multiple ways that help to reduce carbon emissions.[49] Insulation and energy-efficient windows are commonly used in colder cities. Incorporation of features such as solar panels, green roofs and walls, and heat pumps into new or existing buildings can significantly reduce energy use.[50] New types of materials such as smart glass are being developed to improve the energy efficiency of buildings.[51]

Energy efficiency is not the only factor to consider. Types of materials used can vary widely in both their up-front and over-time carbon costs. It is important to carefully consider the up-front embodied emissions of existing materials.[52][53][54][55][56] Researchers are also working to develop construction materials that do not release carbon during manufacturing or that can absorb and store more carbon.[3][57] Steel and cement are heavily used in construction and are very energy intensive to make. Biomass-based materials such as wood and bamboo have lower energy-formation costs. Practices for recycling and reusing construction waste can also save on the amount of energy that has gone into producing and transporting materials.[7]

The size of buildings has an impact on their energy costs in terms of both construction and use.[7] Some recommend a four-storey multi-family building built of low-carbon higher density materials such as straw and wood as an ideal.[58] Mid-size multi-unit buildings can support economies of scale during building and are likely to be more economical in use than single-unit homes. High-rise buildings, particularly in hot climates, are more costly to cool and operate. When planning an area, a mix of mid- and high-rise buildings in a compact urban format is likely to be efficient.[7]

Green infrastructure

Green infrastructure includes private and public garden areas, parks, trees, and urban agriculture. Green infrastructure mitigates the effects of carbon emissions in multiple ways, by naturally removing and storing carbon dioxide, and by shading and cooling surrounding areas which reduces energy needs for cooling. The development of green space in cities, particularly long-lived trees, is a cost-effective method of carbon sequestration.[7][59] The inclusion of green space in urban areas can also help with wide variety of other issues, from stormwater[60] to mental health.[61]

Waste and energy exchange

Wastes can be managed through a variety of ways, including reuse, recycling, storage, treatment, energy recovery, and disposal.[62] In some cases, a by-product of one set of processes can be used to advantage by someone else, sometimes referred to as urban industrial symbiosis.[7] For example, waste heat from industries and grocery stores has been used to heat residential and commercial buildings.[63] The city of Charlotte, North Carolina has identified becoming a zero waste city as one of four key areas of performance for the goal of developing a circular economy.[21]

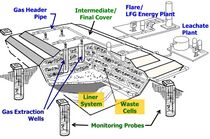

"Waste-to-energy" describes processes through which useful by-products such as energy can be recovered from otherwise unusable sources.[64] Technologies for carbon capture and storage are being developed to mitigate emissions from fossil fuel power plants and industrial sources.[65] The collection and disposal of waste can potentially be used for the generation of electricity, steam, or heat, but systems to support this are not yet well developed.[66][67]

Reviews of attempts to attain zero-waste note that the term is used widely and not consistently. Many countries lack an overall zero waste strategy.[68] In most cases in the United States, waste management is inefficient.[62] Without clear national zero waste strategy and policies that identify key areas, it is difficult to coordinate and promote zero waste initiatives in communities and industry.[68][10]

Measuring net zero

Assessing the urban carbon footprint of cities is a complex issue.[6][29][28][18][69][70][71] Four major accounting systems for measuring urban greenhouse gases have been developed, each with a slightly different conceptualization of what it means to be a net-zero carbon city: territorial source-based accounting, community-wide infrastructure supply chain greenhouse gas footprinting, consumption-based GHG accounting, and total community-wide greenhouse gas footprinting.[7][18][72][73][74] The United Kingdom is one example of a country that is measuring greenhouse gas emissions and assessing its progress towards net zero using a variety of different official measures.[75]

Examples

Converting existing cities

Increasingly, existing cities are planning to become low or zero carbon. As of 2022[update], over 1000 cities worldwide have undertaken steps to transition in response to climate change as part of the Cities Race to Zero campaign,[13][22] one part of the larger United Nations Race to Zero campaign.[14] In the United States, more than 100 cities have pledged to participate in Cities Race to Zero.[17] The following examples illustrate some of the types of initiatives for net zero cities, the extent to which they received multi-level support, and their impact.[7]

Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

As the second largest city in Zimbabwe, with an urban population between 680,000 and 1.5 million people, Bulawayo has gone through a period of rapid growth in the twentieth century; an economic decline in the first decade of the twenty-first century; and next a return to rapid growth that incorporates the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals into the city's strategic plan. Bulawayo hopes to "leapfrog" over existing technology and recreate its economy by adopting next generation technology.[7]

Initiatives include replacement of the city's power station with renewable solar power, "Trackless Trams" for transit, smart technologies for electrical grid management, and circular economy technologies to manage and reduce waste.[7] Researchers are also examining fuelwood production and the potential for carbon sequestration in Bulawayo's public green spaces.[77]

Canberra, Australia

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) which contains the capital Canberra, Australia was the first area in Australia to adopt a net-zero process for an entire urban region. Canberra is known for its strong urban planning and attention to climate change objectives.[7][79]

ACT passed a Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act as of 2010. Its Climate Council set 5-year goals with regular progress reports. As reported in Climate Change Strategy 2019–2025 (2019), Canberra committed to reducing emissions by 40% from 1990 to 2020. It has achieved that goal by shifting to the purchase of 100% renewable energy sources through the National Electricity Grid. The city has also improved transportation through the use of zero emissions light rail and buses, and added cycling paths. Through these and other initiatives, Canberra's current goal is to use 100% renewable energy by 2045.[7][79]

Chongming, China

Over the last decade, Shanghai, China has implemented dozens of low carbon policies to reduce energy usage and address the effects of climate change.[11] Chongming Island, once a rural area of Shanghai, is one focus for net zero city development. In 2001, the Shanghai Municipal Government (SMG) proposed the creation of a low-carbon eco-island to explore the potential for the development of low-carbon cities. The American firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was competitively chosen as the designer of the Chongming Master Plan in 2004.[7][81][82]

In 2010, SMG developed the Chongming Eco-Island Construction Outline as a framework with indicators for redesigning Chongming. These included using energy-saving materials, recycled materials and solar energy to construct new buildings; upgrading existing buildings to save energy; closing the existing coal plant; developing renewable energy sources (wind, solar, and biogas); converting buses to electric vehicles and adding foot and bicycle paths; recycling wastewater with low-carbon techniques; reusing wastes for organic fertilizer and biogas; and the development of forests and wetlands to sequester carbon. Factories were required to meet strict ecological requirements or shut down; economic development has been slow and many residents are unemployed.[7][81][82]

Copenhagen, Denmark

In 2012 Copenhagen, Denmark created the CPH2025 Climate Plan with the target of becoming the first carbon-neutral capital by 2025 and for Denmark to be entirely carbon-neutral by 2050.[83] The city has shifted energy and heating systems to use wind, solar and biomass for heating and sea water for cooling; improved transit by using electric cars and adding bicycle paths, and renovated buildings to be more energy efficient.[84][85] From 2009-2022, Copenhagen reduced CO

2 emissions by 80%.[83]

To achieve the remaining 20% reduction, the city hoped to use carbon capture and storage (CCS). In 2022, the state indicated that the proposed Amager Resource Centre (ARC) incinerator would not qualify for state financial aid under equity capital requirements of the state's CCS funding program. Copenhagen has stated that it still hopes to achieve a 100% reduction in carbon emissions, but will not be able to do so by 2025.[83]

Denver, USA

Denver, Colorado is an established city with aging building stock. It signed its first Climate Action Plan in 2007 with the initial low-carbon goal of reducing emissions per capita by 10% by 2012. Denver achieved this goal as a result of the passage of renewable portfolio standards by the State of Colorado and climate actions on the part of the city.[7]

The city carefully tracked the progress of its climate action plans in detail and modelled the effects of its programs. They determined that low-carbon actions focusing on efficiency and conservation would be insufficient to reduce GHG emissions at the levels desired. In 2018, Denver changed its strategy to deep decarbonization. Denver is now proposing to make broad systemic changes with the goal of reducing emissions by 80% by 2050.[7]

Constructing new cities

The following examples were prototyped to be newly built zero-carbon cities: Dongtan,[91] China and Masdar City, United Arab Emirates.

Dongtan, Shanghai

Dongtan, China was a sustainable eco-city project planned in the 2000s that was never built. Dongtan was to be located at the east end of Chongming Island, adjacent to the Chongming Dongtan National Nature Reserve.[92] The developers planned on a fully built city, with 80,000 residents by 2020.[93]

The planned city's urban design addressed issues of sustainable energy management, waste management, renewable energy process implementation, architecture, infrastructure, and even the planning of communities and social structures. It proposed to use renewable energy, electric battery or hydrogen-fuel cell transportation, recycled water, hydroponic farming, organic waste recycling and waste-generation of clean energy.[92]

However, by 2008, support for the project had disappeared. Reasons for the project's closure include its proposed location in a highly-valued wetlands area, tensions between its development partners (Arup, a British engineering company, and Shanghai Industrial Investment, a state-owned developer), and loss of political support (due to the jailing of Dongtan's top political backer, former Shanghai Communist Party chief Chen Liangyu, on corruption charges in 2008).[94][95]

Although the project was not implemented, as an example of urban design it has inspired and informed other cities in China and worldwide.[91] Ideas from Dongtan were incorporated into the renovation of the Chongming District. Dongtan became a model for a subsequently planned eco-city outside Tianjin.[96]

Masdar City, United Arab Emirates

For the Masdar Initiative, Foster + Partners designed a 2.5-square-mile sustainable carbon and waste-free city combining the principles of an ancient walled city with modern alternative energy technologies. One of the city's goals was to be self-sufficient in energy by using about 80% solar energy, along with wind and biomass sources. Solar energy was to be generated through photovoltaic panels, concentrated solar collectors, and solar thermal tubes.[97] The city was designed with wind cooling towers and narrow streets to maximize shaded areas and keep cooling costs down. Buildings incorporate solar and geo-thermal cooling as well as using high-tech construction materials and siting.[98]

Economically, the city was planned to become a center for alternative energy and technology development as well as an example of their use. The site was located close to Abu Dhabi and an international airport, connecting to surrounding communities through a transportation infrastructure of rail, road and public transit. Transportation within the city was to use battery-powered and auto piloted personal rapid transit systems (PRT) as well as walking and cycling. Visitors to the city must park their cars outside and use public transit.[93]

Construction was planned to occur in phases and began in February 2008. As of 2010, the first buildings went into use in the first section to be completed, a 3 1⁄2-acre zone that included the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology.[99] Shams Solar Power Station (SHAMS 1), Masdar City's main source of power, became operational in 2013, with a capacity of 100 megawatts.[100] It was the largest concentrated solar power (CSP) facility in the world at that time.[101][102]

Originally projected to be completed by 2015, the city's construction was significantly delayed due to the 2008 financial crisis.[103] In 2017, Masdar City completed a pilot project for an Eco-Villa, a 405 square-metre four-bedroom property[104] presented as an affordable net zero energy family home.[105][106] As of 2020[update], only a small part of the city had been finished. Many of those who work there are commuters, not residents. Completion of the city was projected to occur in 2030.[107] In 2022, the city announced its next expansion, Masdar City Square (MC2), to be completed by 2024. It will add seven new office buildings including the city's first net-zero energy office building.[108][109]

Masdar City has experienced setbacks, and has not yet reached its goals. It can be viewed as a lesson in the importance of balancing social, environmental and economic factors in city design. Nonetheless, Masdar City is credited with developing and implementing important technologies for resilient sustainable cities, and with inspiring others worldwide.[98][110]

See also

- 15-minute city

- BSI PAS 2060

- Beyond Zero Emissions

- C40 Cities

- Carfree city

- Compact city

- Ecology movement

- Electric vehicle network

- Environmental movement

- Environmental protection

- Environmentalism

- Geothermal heat pump

- Habitat conservation

- Healthy city

- List of most-polluted cities by particulate matter concentration

- List of smart cities

- Natural environment

- Renewable energy sources

- Smart city

- Sustainable city

- Sustainable development

- Thin film solar on standing seam metal roofs

- Urban vitality

- Zero-emissions vehicle

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fuller-Wright, Liz (March 30, 2022). "What climate choices should cities make? A Princeton data tool helps planners set priorities." (in en). Princeton University. https://www.princeton.edu/news/2022/03/30/city-planners-can-make-smarter-climate-choices-using-new-princeton-data-tool.

- ↑ "DOCSOC/1508196v1/022283-0050 Memorandum of Understanding". 2011. https://www.cityoflancasterca.org/Home/ShowDocument?id=14808.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Padmanaban, Deepa (2022). "How cities can fight climate change". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-060922-1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Towards the Zero-Carbon City. HSBC Centre of Sustainable Finance. July 2019. https://www.sustainablefinance.hsbc.com/-/media/gbm/sustainable/attachments/towards-the-zero-carbon-city.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Allen, Myles R.; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Girardin, Cécile A.J.; Jenkins, Stuart; Malhi, Yadvinder; Mitchell-Larson, Eli; Peters, Glen P.; Rajamani, Lavanya (17 October 2022). "Net Zero: Science, Origins, and Implications". Annual Review of Environment and Resources 47 (1): annurev–environ–112320-105050. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-112320-105050.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kelly, Morgan (May 13, 2021). "What is a net-zero city? Depends on how you count urban carbon emissions". High Meadows Environmental Institute (Princeton University). https://environment.princeton.edu/news/what-is-a-net-zero-city-depends-on-how-you-count-urban-carbon-emissions/.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 Seto, Karen C.; Churkina, Galina; Hsu, Angel; Keller, Meredith; Newman, Peter W.G.; Qin, Bo; Ramaswami, Anu (18 October 2021). "From Low- to Net-Zero Carbon Cities: The Next Global Agenda". Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46 (1): 377–415. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-050120-113117.

- ↑ Owen-Burge, Charlotte (6 May 2021). "Carbon neutral cities: Can we fight climate change without them?" (in en). Climate Champions. https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/carbon-neutral-cities-can-we-fight-climate-change-without-them/.

- ↑ "Cities: a "cause of and solution to" climate change" (in en). 18 September 2019. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/09/1046662.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Empowering Cities for a Net Zero Future: Unlocking resilient, smart, sustainable urban energy systems". 2021. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4d5c939d-9c37-490b-bb53-2c0d23f2cf3d/G20EmpoweringCitiesforaNetZeroFuture.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Peng, Yuan; Bai, Xuemei (February 2018). "Experimenting towards a low-carbon city: Policy evolution and nested structure of innovation". Journal of Cleaner Production 174: 201–212. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.116. Bibcode: 2018JCPro.174..201P.

- ↑ Morris, Langdon; Naz, Farah (2021). Net Zero City: The Ten-year Transformation Plan : how to Overcome the Climate Crisis by 2032. Langdon Morris. ISBN 979-8-4653-6115-6.[page needed]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Wray, Sarah (2 November 2021). "'We need to do more': COP26 city highlights – November 2". Cities Today. https://cities-today.com/we-need-to-do-more-cop26-city-highlights-november-2/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bindman, Polly (22 July 2022). "Which cities are in the race to net zero?". Capital Monitor. https://capitalmonitor.ai/sdgs/sdg-11-sustainable-cities-and-communities/green-cities-race-net-zero/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Brown, Jessica (16 November 2021). "How cities are going carbon neutral" (in en). www.bbc.com. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20211115-how-cities-are-going-carbon-neutral.

- ↑ "Who's in Race to Zero?". https://unfccc.int/climate-action/race-to-zero/who-s-in-race-to-zero.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "More than 100 American Cities Make Historic Pledge to Accelerate Net-Zero Emissions, Deliver Action Needed to Meet National Climate Goals". C40 Cities. October 25, 2021. https://www.c40.org/news/american-cities-net-zero-climate-goals/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Ramaswami, Anu; Tong, Kangkang; Canadell, Josep G.; Jackson, Robert B.; Stokes, Eleanor (Kellie); Dhakal, Shobhakar; Finch, Mario; Jittrapirom, Peraphan et al. (June 2021). "Carbon analytics for net-zero emissions sustainable cities". Nature Sustainability 4 (6): 460–463. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00715-5. Bibcode: 2021NatSu...4..460R.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Dabaieh, Marwa; Maguid, Dalya; El Mahdy, Deena (2019). "Towards Adaptive Design Strategies for Zero-Carbon Eco-Cities in Egypt". Sustainable Cities - Authenticity, Ambition and Dream. doi:10.5772/intechopen.80725. ISBN 978-1-78985-523-4.Template:Predatory

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 20.12 Fankhauser, Sam; Smith, Stephen M.; Allen, Myles; Axelsson, Kaya; Hale, Thomas; Hepburn, Cameron; Kendall, J. Michael; Khosla, Radhika et al. (January 2022). "The meaning of net zero and how to get it right". Nature Climate Change 12 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01245-w. Bibcode: 2022NatCC..12...15F.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 (in en) Circular Charlotte: Towards a zero waste and inclusive city. Charlotte, North Carolina: City of Charlotte. 2018. https://charlottenc.gov/SWS/CircularCharlotte/Documents/Circular%20Charlotte_Towards%20a%20zero%20waste%20and%20inclusive%20city%20-%20full%20report.pdf. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "From LA to Bogotá to London, global mayors unite to deliver critical city momentum to world leaders tasked with keeping 1.5 degree hopes alive at Glasgow's COP26". November 2, 2021. https://www.c40.org/news/cop-26-cities-race-to-zero/.

- ↑ Larose, Lysanne (September 9, 2022). "Most climate policies worldwide do not consider the rights of people with disabilities". CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/what-on-earth-climate-action-people-with-disabilities-1.6576205.

- ↑ Burg, Natalie (April 20, 2022). "Who Funds the Fight Against Climate Change?". Means and Matters. https://meansandmatters.bankofthewest.com/article/sustainable-living/taking-action/who-funds-the-fight-against-climate-change/.

- ↑ Roseland, Mark (August 1997). "Dimensions of the eco-city". Cities 14 (4): 197–202. doi:10.1016/s0264-2751(97)00003-6.

- ↑ Reeves, Martin; Young, David; Dhar, Julia; O'Dea, Annelies (February 28, 2022). "The risks and benefits for companies going net zero" (in en). World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/net-zero-risks-benefits-climate/.

- ↑ Creutzig, Felix; Baiocchi, Giovanni; Bierkandt, Robert; Pichler, Peter-Paul; Seto, Karen C. (19 May 2015). "Global typology of urban energy use and potentials for an urbanization mitigation wedge". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (20): 6283–6288. doi:10.1073/pnas.1315545112. PMID 25583508. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.6283C.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Michie, Craig; Cohen, Ronald (December 17, 2021). "How measuring emissions in real time can help cities achieve net zero" (in en). The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-measuring-emissions-in-real-time-can-help-cities-achieve-net-zero-172651.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "How to determine your city's net zero carbon buildings strategy". 2022. https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/How-to-determine-your-city-s-net-zero-carbon-buildings-strategy?language=en_US.

- ↑ "Empowering "Smart Cities" toward net zero emissions - News". 22 July 2021. https://www.iea.org/news/empowering-smart-cities-toward-net-zero-emissions.

- ↑ Sederman, Adelina (18 March 2022). "The Clean Energy Home Series (Part 3): What are Electric and Induction Cooktops?". https://environmentamerica.org/center/articles/the-clean-energy-home-series-part-3-what-are-electric-and-induction-cooktops/.

- ↑ McKivigan, Meg St-Esprit (February 17, 2022). "How electric stoves are poised to dethrone the mighty gas range". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/home/2022/02/17/induction-cooktops-healthier-alternative-to-gas-stove/.

- ↑ Woods, Jeremy; Williams, Adrian; Hughes, John K.; Black, Mairi; Murphy, Richard (27 September 2010). "Energy and the food system". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365 (1554): 2991–3006. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0172. PMID 20713398.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Selvanandan, Vamini (19 September 2022). "COMMENTARY: Food for a healthy planet and healthy people" (in en). RMOToday.com. https://www.rmotoday.com/opinion/commentary-food-for-a-healthy-planet-and-healthy-people-5807684.

- ↑ Norton, Daphne. "Energy Expenditures Related to Food Production". https://sustainability.emory.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/InfoSheet-Energy26FoodProduction.pdf.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 McClements, David Julian; Barrangou, Rodolphe; Hill, Colin; Kokini, Jozef L.; Lila, Mary Ann; Meyer, Anne S.; Yu, Liangli (25 March 2021). "Building a Resilient, Sustainable, and Healthier Food Supply Through Innovation and Technology". Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 12 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1146/annurev-food-092220-030824. PMID 33348992.

- ↑ Baylis, Kathy; Heckelei, Thomas; Hertel, Thomas W. (5 October 2021). "Agricultural Trade and Environmental Sustainability". Annual Review of Resource Economics 13 (1): 379–401. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-101420-090453.

- ↑ Bankova, Dea; Dutta, Prasanta Kumar; Ovaska, Michael (May 30, 2022). "The war in Ukraine is fuelling a global food crisis" (in en). Reuters. https://graphics.reuters.com/UKRAINE-CRISIS/FOOD/zjvqkgomjvx/.

- ↑ "Climate Change". http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/natural-resources-environment/climate-change.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Mugica, Yerina; Rose, Terra (2019). Tackling Food Waste in Cities - A Policy and Program Toolkit. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/food-waste-cities-policy-toolkit-report.pdf. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Food systems can lead the way to net zero, if we act now" (in en). World Economic Forum. March 16, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/food-systems-net-zero/.

- ↑ "How to Start a Food Rescue Program in Your Community". https://www.cityharvest.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/StartaFoodRescueOrg.pdf.

- ↑ Povich, Elaine S. (July 9, 2021). "Waste Not? Some States Are Sending Less Food to Landfills" (in en). pew.org. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/07/08/waste-not-some-states-are-sending-less-food-to-landfills.

- ↑ Spang, Edward S.; Moreno, Laura C.; Pace, Sara A.; Achmon, Yigal; Donis-Gonzalez, Irwin; Gosliner, Wendi A.; Jablonski-Sheffield, Madison P.; Momin, Md Abdul et al. (17 October 2019). "Food Loss and Waste: Measurement, Drivers, and Solutions". Annual Review of Environment and Resources 44 (1): 117–156. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033228.

- ↑ Kaza, Silpa; Yao, Lisa C.; Bhada-Tata, Perinaz; Van Woerden, Frank (20 September 2018). What a Waste 2.0. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1329-0. ISBN 978-1-4648-1329-0.

- ↑ Niles, Meredith T.; Ahuja, Richie; Barker, Todd; Esquivel, Jimena; Gutterman, Sophie; Heller, Martin C.; Mango, Nelson; Portner, Diana et al. (June 2018). "Climate change mitigation beyond agriculture: a review of food system opportunities and implications". Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 33 (3): 297–308. doi:10.1017/S1742170518000029.

- ↑ Anyiam, P. N.; Adimuko, G. C.; Nwamadi, C. P.; Guibunda, F. A.; Kamale, Y. J. (31 December 2021). "Sustainable Food System Transformation in a Changing Climate". Nigeria Agricultural Journal 52 (3): 105–115. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/naj/article/view/223414.

- ↑ Miao, Ruiqing; Khanna, Madhu (6 October 2020). "Harnessing Advances in Agricultural Technologies to Optimize Resource Utilization in the Food-Energy-Water Nexus". Annual Review of Resource Economics 12 (1): 65–85. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-110319-115428.

- ↑ "Net Zero: what to measure and where to begin.". 7 April 2020. https://hoarelea.com/2020/04/07/net-zero-what-to-measure-and-where-to-begin/.

- ↑ Pell, Billy (9 May 2019). "Energy Efficient Building Design: 23 Key Features To Consider". https://aeroseal.com/air-duct-sealing-blog/energy-efficient-building-design/.

- ↑ Miller, Brittney J. (2022). "How smart windows save energy". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-060822-3.

- ↑ Jungclaus, Matt; Esau, Rebecca; Olgyay, Victor; Rempher, Audrey (2021). Reducing Embodied Carbon in Buildings Low-Cost, High-Value Opportunities. RMI. https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2021/08/Embodied_Carbon_full_report.pdf.

- ↑ King, Bruce; Magwood, Chris (2022). Build beyond zero : new ideas for carbon-smart architecture. Washington D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 9781642832112.

- ↑ Magwood, Chris; Bowden, Erik; Trottier, Melanie (2022). Emissions of Materials Benchmark Assessment for Residential Construction (EMBARC) (Report). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.34242.66243.

- ↑ Magwood, Chris (2019). Opportunities for CO2 Capture and Storage in Building Materials (Thesis). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32171.39208.

- ↑ Kreps, Bart Hawkins (9 August 2022). "'Getting to zero' is a lousy goal". Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2022-08-09/getting-to-zero-is-a-lousy-goal/.

- ↑ Ürge-Vorsatz, Diana; Khosla, Radhika; Bernhardt, Rob; Chan, Yi Chieh; Vérez, David; Hu, Shan; Cabeza, Luisa F. (17 October 2020). "Advances Toward a Net-Zero Global Building Sector". Annual Review of Environment and Resources 45 (1): 227–269. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012420-045843.

- ↑ Alter, Lloyd (December 10, 2019). "Landmark Study Shows How to Change the Building Sector From a Major Carbon Emitter to a Major Carbon Sink" (in en). Treehugger. https://www.treehugger.com/green-architecture/landmark-study-shows-how-change-building-sector-major-carbon-emitter-major-carbon-sink.html.

- ↑ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2022). "What can cities do to survive extreme heat?". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-101922-2.

- ↑ Fourth Economy (May 2021). Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) A Tool for Economic Recovery and Growth in Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh, PA: Sustainable Business Network of Greater Philadelphia. https://www.sbnphiladelphia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GSI_A-Tool-for-Economic-Recovery-and-Growth-in-PA_doubleview.pdf. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ Kruize, Hanneke; van der Vliet, Nina; Staatsen, Brigit; Bell, Ruth; Chiabai, Aline; Muiños, Gabriel; Higgins, Sahran; Quiroga, Sonia et al. (11 November 2019). "Urban Green Space: Creating a Triple Win for Environmental Sustainability, Health, and Health Equity through Behavior Change". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (22): 4403. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224403. PMID 31717956.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Wastes" (in en). 2 November 2017. https://www.epa.gov/report-environment/wastes.

- ↑ Lund, Peter D.; Mikkola, Jani; Ypyä, J. (15 September 2015). "Smart energy system design for large clean power schemes in urban areas". Journal of Cleaner Production 103: 437–445. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.005. Bibcode: 2015JCPro.103..437L.

- ↑ Murphy, Michael L. (2004). "Waste-to-Energy Technology". Encyclopedia of Energy. pp. 373–383. doi:10.1016/B0-12-176480-X/00359-4. ISBN 978-0-12-176480-7.

- ↑ Abdulla, Ahmed; Hanna, Ryan; Schell, Kristen R.; Babacan, Oytun et al. (29 December 2020). "Explaining successful and failed investments in U.S. carbon capture and storage using empirical and expert assessments". Environmental Research Letters 16 (1): 014036. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abd19e.

- ↑ Narayan, Abishek Sankara; Marks, Sara J.; Meierhofer, Regula; Strande, Linda; Tilley, Elizabeth; Zurbrügg, Christian; Lüthi, Christoph (18 October 2021). "Advancements in and Integration of Water, Sanitation, and Solid Waste for Low- and Middle-Income Countries". Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46 (1): 193–219. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-030620-042304.

- ↑ Huovila, Aapo; Siikavirta, Hanne; Antuña Rozado, Carmen; Rökman, Jyri; Tuominen, Pekka; Paiho, Satu; Hedman, Åsa; Ylén, Peter (20 March 2022). "Carbon-neutral cities: Critical review of theory and practice". Journal of Cleaner Production 341. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130912. Bibcode: 2022JCPro.34130912H.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Zaman, Atiq Uz (2015). "A comprehensive review of the development of zero waste management: lessons learned and guidelines". Journal of Cleaner Production 91: 12–25. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.013. Bibcode: 2015JCPro..91...12Z.

- ↑ Huo, Da; Huang, Xiaoting; Dou, Xinyu; Ciais, Philippe; Li, Yun; Deng, Zhu; Wang, Yilong; Cui, Duo et al. (1 September 2022). "Carbon Monitor Cities near-real-time daily estimates of CO

2 emissions from 1500 cities worldwide". Scientific Data 9 (1): 533. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01657-z. PMID 36050332. Bibcode: 2022NatSD...9..533H. - ↑ Moran, Daniel; Kanemoto, Keiichiro; Jiborn, Magnus; Wood, Richard; Többen, Johannes; Seto, Karen C (1 June 2018). "Carbon footprints of 13 000 cities". Environmental Research Letters 13 (6): 064041. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aac72a. Bibcode: 2018ERL....13f4041M.

- ↑ "What is your carbon footprint?". https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/carbon-footprint-calculator/.

- ↑ Heinonen, Jukka; Ottelin, Juudit; Ala-Mantila, Sanna; Wiedmann, Thomas; Clarke, Jack; Junnila, Seppo (20 May 2020). "Spatial consumption-based carbon footprint assessments - A review of recent developments in the field". Journal of Cleaner Production 256. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120335. Bibcode: 2020JCPro.25620335H.

- ↑ Lombardi, Mariarosaria; Laiola, Elisabetta; Tricase, Caterina; Rana, Roberto (1 September 2017). "Assessing the urban carbon footprint: An overview". Environmental Impact Assessment Review 66: 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2017.06.005. Bibcode: 2017EIARv..66...43L.

- ↑ Chavez, Abel; Ramaswami, Anu (1 March 2013). "Articulating a trans-boundary infrastructure supply chain greenhouse gas emission footprint for cities: Mathematical relationships and policy relevance". Energy Policy 54: 376–384. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.037. Bibcode: 2013EnPol..54..376C.

- ↑ "Net zero and the different official measures of the UK's greenhouse gas emissions - Office for National Statistics". 24 July 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/articles/netzeroandthedifferentofficialmeasuresoftheuksgreenhousegasemissions/2019-07-24#measuring-the-uks-progress-to-net-zero.

- ↑ The Dry Forests and Woodlands of Africa. 2010. doi:10.4324/9781849776547. ISBN 978-1-136-53138-5.[page needed]

- ↑ Ngulani, Thembelihle; Shackleton, Charlie M. (May 2022). "Fuelwood Production and Carbon Sequestration in Public Urban Green Spaces in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe". Forests 13 (5): 741. doi:10.3390/f13050741. Bibcode: 2022Fore...13..741N.

- ↑ "CMET is committed to delivering a safe, efficient rail network that creates environmental, social and economic benefit for Canberra". 2 August 2018. https://cmet.com.au/about/sustainability/.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Australian Capital Territory. Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate (2019). Canberra's living infrastructure plan : cooling the city.. Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory: Australian Capital Territory, Canberra. ISBN 978-1-921117-84-8. https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1414641/ACT-Climate-Change-Strategy-2019-2025.pdf. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ Wang, Zhe; Cui, Xuan; Yin, Shan; Shen, GuangRong; Han, YuJie; Liu, ChunJiang (April 2013). "Characteristics of carbon storage in Shanghai's urban forest". Chinese Science Bulletin 58 (10): 1130–1138. doi:10.1007/s11434-012-5443-1. Bibcode: 2013ChSBu..58.1130W.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Yi, Shi (June 28, 2021). "Shanghai leads way in China's carbon transition" (in en). Eco-Business. https://www.eco-business.com/news/shanghai-leads-way-in-chinas-carbon-transition/.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Zhao, Changying; Ju, Shenghong; Xue, Yuan; Ren, Tao; Ji, Ya; Chen, Xue (19 April 2022). "China's energy transitions for carbon neutrality: challenges and opportunities". Carbon Neutrality 1 (1): 7. doi:10.1007/s43979-022-00010-y. Bibcode: 2022CarNe...1....7Z.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Szumski, Charles (23 August 2022). "Copenhagen's dream of being carbon neutral by 2025 goes up in smoke". www.euractiv.com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/copenhagens-dream-of-being-carbon-neutral-by-2025-go-up-in-smoke/.

- ↑ Gerdes, Justin (12 April 2013). "Copenhagen's ambitious push to be carbon-neutral by 2025" (in en). the Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/apr/12/copenhagen-push-carbon-neutral-2025.

- ↑ "Carbon neutral capital" (in en). https://international.kk.dk/carbon-neutral-capital.

- ↑ Caulfield, John (6 February 2018). "Takeaways for Builders From the Solar Decathlon" (in en). Professional Builder. https://www.probuilder.com/takeaways-builders-solar-decathlon.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Xie, Jenny (17 October 2017). "Tour 11 solar-powered homes that push the limits of sustainable living" (in en). Curbed. https://archive.curbed.com/2017/10/17/16455382/solar-decathlon-2017-teams-houses-winner.

- ↑ "Solar Decathlon 2017: Washington University – St. Louis". https://www.solardecathlon.gov/2017/where-is-wash-u-now.html.

- ↑ "Solar Decathlon 2017: Team Daytona Beach: Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and Daytona State College". https://www.solardecathlon.gov/2017/where-is-daytona-beach-now.html.

- ↑ "Solar Decathlon: High-Resolution Event Photos". https://www.solardecathlon.gov/2017/photos-event.html.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Chang, I-Chun Catherine (August 2017). "Failure matters: Reassembling eco-urbanism in a globalizing China". Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (8): 1719–1742. doi:10.1177/0308518X16685092. Bibcode: 2017EnPlA..49.1719C.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Hart, Sara (March 19, 2007). "Zero-Carbon Cities" (in en). Architectural Record. https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/6699-zero-carbon-cities.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Cheng, Hefa; Hu, Yuanan (2010). "Planning for sustainability in China's urban development: Status and challenges for Dongtan eco-city project". J. Environ. Monit. 12 (1): 119–126. doi:10.1039/b911473d. PMID 20082005.

- ↑ Brenhouse, Hillary (24 June 2010). "Plans Shrivel for Chinese Eco-City". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/25/business/energy-environment/25iht-rbogdong.html.

- ↑ McGirk, Jan (May 27, 2015). "Why eco-cities fail" (in en). China Dialogue. https://chinadialogue.net/en/cities/7934-why-eco-cities-fail/.

- ↑ Chang, I-Chun Catherine; Sheppard, Eric (January 2013). "China's Eco-Cities as Variegated 1 Urban Sustainability: Dongtan Eco-City and Chongming Eco-Island". Journal of Urban Technology 20 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1080/10630732.2012.735104.

- ↑ Mckenna, Phil (6 May 2008). "First zero-carbon city to rise out of the desert". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn13838-first-zerocarbon-city-to-rise-out-of-the-desert.html.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Lee, Susan (30 September 2016). "Masdar City: The ultimate experiment in sustainable urban living?" (in en). CNN. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/conversation-masdar-city-lee/index.html.

- ↑ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (25 September 2010). "In Arabian Desert, a Sustainable City Rises". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/26/arts/design/26masdar.html.

- ↑ "Shams 1 | Concentrating Solar Power Projects". https://solarpaces.nrel.gov/project/shams-1.

- ↑ Quick, Darren (19 March 2013). "World's largest concentrated solar power plant opens in the UAE". New Atlas. https://newatlas.com/shams-1-worlds-largest-concentrated-solar-power-plant/26707/.

- ↑ Dennehy, John (18 August 2022). "From the deserts of Abu Dhabi to the world, how Masdar is building a greener tomorrow" (in en). The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/2022/08/18/from-the-deserts-of-abu-dhabi-to-the-world-how-masdar-is-building-a-greener-tomorrow/.

- ↑ Walsh, Bryan (25 January 2011). "Masdar City: The World's Greenest City?". Time. http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,2043934,00.html. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ↑ "Eco-Villa prototype opens its doors at Masdar City - News - Emirates" (in en). Emirates247. January 20, 2017. https://www.emirates247.com/news/emirates/eco-villa-prototype-opens-its-doors-at-masdar-city-2017-01-20-1.646752.

- ↑ Gibbon, Gavin (26 Dec 2019). "Masdar's eco-villas to be designed for Emirati households". Arabian Business. https://www.arabianbusiness.com/gcc/uae/436155-masdars-eco-villas-to-be-designed-for-emirati-households.

- ↑ "Masdar City Unveils Eco-Villa, the First Net-Zero Energy House - INVEST-GATE". invest-gate.me. 22 January 2017. https://invest-gate.me/news/masdar-city-unveils-eco-villa-the-first-net-zero-energy-house/.

- ↑ Flint, Anthony (14 February 2020). "What Abu Dhabi's City of the Future Looks Like Now" (in en). Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-02-14/the-reality-of-abu-dhabi-s-unfinished-utopia.

- ↑ "Abu Dhabi smart city breaks ground on new development" (in En). Smart Cities World. 6 July 2022. https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/commercial-buildings/commercial-buildings/abu-dhabi-smart-city-breaks-ground-on-new-development-7865.

- ↑ "Masdar City announces new project as it advances contribution to UAE Net-Zero by 2050 Strategy". Living Business. 5 July 2022. https://livingbusiness.com/masdar-city-announces-new-project-as-it-advances-contribution-to-uae-net-zero-by-2050-strategy/.

- ↑ Randeree, Kasim; Ahmed, Nadeem (1 January 2018). "The social imperative in sustainable urban development: The case of Masdar City in the United Arab Emirates". Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 8 (2): 138–149. doi:10.1108/SASBE-11-2017-0064.

|