Frame bundle

In mathematics, a frame bundle is a principal fiber bundle associated with any vector bundle . The fiber of over a point is the set of all ordered bases, or frames, for . The general linear group acts naturally on via a change of basis, giving the frame bundle the structure of a principal -bundle (where k is the rank of ).

The frame bundle of a smooth manifold is the one associated with its tangent bundle. For this reason it is sometimes called the tangent frame bundle.

Definition and construction

Let be a real vector bundle of rank over a topological space . A frame at a point is an ordered basis for the vector space . Equivalently, a frame can be viewed as a linear isomorphism

The set of all frames at , denoted , has a natural right action by the general linear group of invertible matrices: a group element acts on the frame via composition to give a new frame

This action of on is both free and transitive (this follows from the standard linear algebra result that there is a unique invertible linear transformation sending one basis onto another). As a topological space, is homeomorphic to although it lacks a group structure, since there is no "preferred frame". The space is said to be a -torsor.

The frame bundle of , denoted by or , is the disjoint union of all the :

Each point in is a pair (x, p) where is a point in and is a frame at . There is a natural projection which sends to . The group acts on on the right as above. This action is clearly free and the orbits are just the fibers of .

Principal bundle structure

The frame bundle can be given a natural topology and bundle structure determined by that of . Let be a local trivialization of . Then for each x ∈ Ui one has a linear isomorphism . This data determines a bijection

given by

With these bijections, each can be given the topology of . The topology on is the final topology coinduced by the inclusion maps .

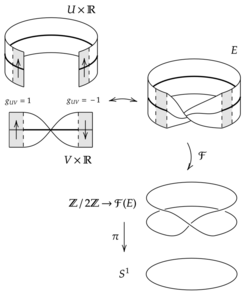

With all of the above data the frame bundle becomes a principal fiber bundle over with structure group and local trivializations . One can check that the transition functions of are the same as those of .

The above all works in the smooth category as well: if is a smooth vector bundle over a smooth manifold then the frame bundle of can be given the structure of a smooth principal bundle over .

Associated vector bundles

A vector bundle and its frame bundle are associated bundles. Each one determines the other. The frame bundle can be constructed from as above, or more abstractly using the fiber bundle construction theorem. With the latter method, is the fiber bundle with same base, structure group, trivializing neighborhoods, and transition functions as but with abstract fiber , where the action of structure group on the fiber is that of left multiplication.

Given any linear representation there is a vector bundle

associated with which is given by product modulo the equivalence relation for all in . Denote the equivalence classes by .

The vector bundle is naturally isomorphic to the bundle where is the fundamental representation of on . The isomorphism is given by

where is a vector in and is a frame at . One can easily check that this map is well-defined.

Any vector bundle associated with can be given by the above construction. For example, the dual bundle of is given by where is the dual of the fundamental representation. Tensor bundles of can be constructed in a similar manner.

Tangent frame bundle

The tangent frame bundle (or simply the frame bundle) of a smooth manifold is the frame bundle associated with the tangent bundle of . The frame bundle of is often denoted or rather than . In physics, it is sometimes denoted . If is -dimensional then the tangent bundle has rank , so the frame bundle of is a principal bundle over .

Smooth frames

Local sections of the frame bundle of are called smooth frames on . The cross-section theorem for principal bundles states that the frame bundle is trivial over any open set in in which admits a smooth frame. Given a smooth frame , the trivialization is given by

where is a frame at . It follows that a manifold is parallelizable if and only if the frame bundle of admits a global section.

Since the tangent bundle of is trivializable over coordinate neighborhoods of so is the frame bundle. In fact, given any coordinate neighborhood with coordinates the coordinate vector fields

define a smooth frame on . One of the advantages of working with frame bundles is that they allow one to work with frames other than coordinates frames; one can choose a frame adapted to the problem at hand. This is sometimes called the method of moving frames.

Solder form

The frame bundle of a manifold is a special type of principal bundle in the sense that its geometry is fundamentally tied to the geometry of . This relationship can be expressed by means of a vector-valued 1-form on called the solder form (also known as the fundamental or tautological 1-form). Let be a point of the manifold and a frame at , so that

is a linear isomorphism of with the tangent space of at . The solder form of is the -valued 1-form defined by

where ξ is a tangent vector to at the point , and is the inverse of the frame map, and is the differential of the projection map . The solder form is horizontal in the sense that it vanishes on vectors tangent to the fibers of and right equivariant in the sense that

where is right translation by . A form with these properties is called a basic or tensorial form on . Such forms are in 1-1 correspondence with -valued 1-forms on which are, in turn, in 1-1 correspondence with smooth bundle maps over . Viewed in this light is just the identity map on .

As a naming convention, the term "tautological one-form" is usually reserved for the case where the form has a canonical definition, as it does here, while "solder form" is more appropriate for those cases where the form is not canonically defined. This convention is not being observed here.

Orthonormal frame bundle

If a vector bundle is equipped with a Riemannian bundle metric then each fiber is not only a vector space but an inner product space. It is then possible to talk about the set of all orthonormal frames for . An orthonormal frame for is an ordered orthonormal basis for , or, equivalently, a linear isometry

where is equipped with the standard Euclidean metric. The orthogonal group acts freely and transitively on the set of all orthonormal frames via right composition. In other words, the set of all orthonormal frames is a right -torsor.

The orthonormal frame bundle of , denoted , is the set of all orthonormal frames at each point in the base space . It can be constructed by a method entirely analogous to that of the ordinary frame bundle. The orthonormal frame bundle of a rank Riemannian vector bundle is a principal -bundle over . Again, the construction works just as well in the smooth category.

If the vector bundle is orientable then one can define the oriented orthonormal frame bundle of , denoted , as the principal -bundle of all positively oriented orthonormal frames.

If is an -dimensional Riemannian manifold, then the orthonormal frame bundle of , denoted or , is the orthonormal frame bundle associated with the tangent bundle of (which is equipped with a Riemannian metric by definition). If is orientable, then one also has the oriented orthonormal frame bundle .

Given a Riemannian vector bundle , the orthonormal frame bundle is a principal -subbundle of the general linear frame bundle. In other words, the inclusion map

is principal bundle map. One says that is a reduction of the structure group of from to .

G-structures

If a smooth manifold comes with additional structure it is often natural to consider a subbundle of the full frame bundle of which is adapted to the given structure. For example, if is a Riemannian manifold we saw above that it is natural to consider the orthonormal frame bundle of . The orthonormal frame bundle is just a reduction of the structure group of to the orthogonal group .

In general, if is a smooth -manifold and is a Lie subgroup of we define a G-structure on to be a reduction of the structure group of to . Explicitly, this is a principal -bundle over together with a -equivariant bundle map

over .

In this language, a Riemannian metric on gives rise to an -structure on . The following are some other examples.

- Every oriented manifold has an oriented frame bundle which is just a -structure on .

- A volume form on determines a -structure on .

- A -dimensional symplectic manifold has a natural -structure.

- A -dimensional complex or almost complex manifold has a natural -structure.

In many of these instances, a -structure on uniquely determines the corresponding structure on . For example, a -structure on determines a volume form on . However, in some cases, such as for symplectic and complex manifolds, an added integrability condition is needed. A -structure on uniquely determines a nondegenerate 2-form on , but for to be symplectic, this 2-form must also be closed.

References

- Kobayashi, Shoshichi; Nomizu, Katsumi (1996), Foundations of Differential Geometry, 1 (New ed.), Wiley Interscience, ISBN 0-471-15733-3

- Kolář, Ivan; Michor, Peter; Slovák, Jan (1993) (PDF), Natural operators in differential geometry, Springer-Verlag, http://www.emis.de/monographs/KSM/kmsbookh.pdf, retrieved 2008-08-02

- Sternberg, S. (1983), Lectures on Differential Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: Chelsea Publishing Co., ISBN 0-8218-1385-4

|