Levi-Civita symbol

In mathematics, particularly in linear algebra, tensor analysis, and differential geometry, the Levi-Civita symbol or Levi-Civita epsilon represents a collection of numbers; defined from the sign of a permutation of the natural numbers 1, 2, ..., n, for some positive integer n. It is named after the Italian mathematician and physicist Tullio Levi-Civita. Other names include the permutation symbol, antisymmetric symbol, or alternating symbol, which refer to its antisymmetric property and definition in terms of permutations.

The standard letters to denote the Levi-Civita symbol are the Greek lower case epsilon ε or ϵ, or the Latin lower case e for the e-matrix in the Cartesian reference system. Index notation allows one to display permutations in a way compatible with tensor analysis: where each index i1, i2, ..., in takes values 1, 2, ..., n. There are nn indexed values of εi1i2...in, which can be arranged into an n-dimensional array. The key defining property of the symbol is total antisymmetry in the indices. When any two indices are interchanged, equal or not, the symbol is negated:

If any two indices are equal, the symbol is zero. When all indices are unequal, we have: where p (called the parity of the permutation) is the number of pairwise interchanges of indices necessary to unscramble i1, i2, ..., in into the order 1, 2, ..., n, and the factor (−1)p is called the sign, or signature of the permutation. The value ε1 2 ... n must be defined, else the particular values of the symbol for all permutations are indeterminate. Most authors choose ε1 2 ... n = +1, which means the Levi-Civita symbol equals the sign of a permutation when the indices are all unequal. This choice is used throughout this article.

The term "n-dimensional Levi-Civita symbol" refers to the fact that the number of indices on the symbol n matches the dimensionality of the vector space in question, which may be Euclidean or non-Euclidean, for example, or Minkowski space. The values of the Levi-Civita symbol are independent of any metric tensor and coordinate system. Also, the specific term "symbol" emphasizes that it is not a tensor because of how it transforms between coordinate systems; however it can be interpreted as a tensor density.

The Levi-Civita symbol allows the determinant of a square matrix, and the cross product of two vectors in three-dimensional Euclidean space, to be expressed in Einstein index notation.

Definition

The Levi-Civita symbol is most often used in three and four dimensions, and to some extent in two dimensions, so these are given here before defining the general case.

Two dimensions

In two dimensions, the Levi-Civita symbol is defined by: The values can be arranged into a 2 × 2 antisymmetric matrix:

Use of the two-dimensional symbol is common in condensed matter, and in certain specialized high-energy topics like supersymmetry[1] and twistor theory,[2] where it appears in the context of 2-spinors.

Three dimensions

In three dimensions, the Levi-Civita symbol is defined by:[3]

That is, εijk is 1 if (i, j, k) is an even permutation of (1, 2, 3), −1 if it is an odd permutation, and 0 if any index is repeated. In three dimensions only, the cyclic permutations of (1, 2, 3) are all even permutations, similarly the anticyclic permutations are all odd permutations. This means in 3d it is sufficient to take cyclic or anticyclic permutations of (1, 2, 3) and easily obtain all the even or odd permutations.

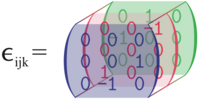

Analogous to 2-dimensional matrices, the values of the 3-dimensional Levi-Civita symbol can be arranged into a 3 × 3 × 3 array:

where i is the depth (blue: i = 1; red: i = 2; green: i = 3), j is the row and k is the column.

Some examples:

Four dimensions

In four dimensions, the Levi-Civita symbol is defined by:

These values can be arranged into a 4 × 4 × 4 × 4 array, although in 4 dimensions and higher this is difficult to draw.

Some examples:

Generalization to n dimensions

More generally, in n dimensions, the Levi-Civita symbol is defined by:[4]

Thus, it is the sign of the permutation in the case of a permutation, and zero otherwise.

Using the capital pi notation Π for ordinary multiplication of numbers, an explicit expression for the symbol is:[citation needed] where the signum function (denoted sgn) returns the sign of its argument while discarding the absolute value if nonzero. The formula is valid for all index values, and for any n (when n = 0 or n = 1, this is the empty product). However, computing the formula above naively has a time complexity of O(n2), whereas the sign can be computed from the parity of the permutation from its disjoint cycles in only O(n log(n)) cost.

Properties

A tensor whose components in an orthonormal basis are given by the Levi-Civita symbol (a tensor of covariant rank n) is sometimes called a permutation tensor.

Under the ordinary transformation rules for tensors the Levi-Civita symbol is unchanged under pure rotations, consistent with that it is (by definition) the same in all coordinate systems related by orthogonal transformations. However, the Levi-Civita symbol is a pseudotensor because under an orthogonal transformation of Jacobian determinant −1, for example, a reflection in an odd number of dimensions, it should acquire a minus sign if it were a tensor. As it does not change at all, the Levi-Civita symbol is, by definition, a pseudotensor.

As the Levi-Civita symbol is a pseudotensor, the result of taking a cross product is a pseudovector, not a vector.[5]

Under a general coordinate change, the components of the permutation tensor are multiplied by the Jacobian of the transformation matrix. This implies that in coordinate frames different from the one in which the tensor was defined, its components can differ from those of the Levi-Civita symbol by an overall factor. If the frame is orthonormal, the factor will be ±1 depending on whether the orientation of the frame is the same or not.[5]

In index-free tensor notation, the Levi-Civita symbol is replaced by the concept of the Hodge dual.

Summation symbols can be eliminated by using Einstein notation, where an index repeated between two or more terms indicates summation over that index. For example,

- .

In the following examples, Einstein notation is used.

Two dimensions

In two dimensions, when all i, j, m, n each take the values 1 and 2:[3]

-

( )

-

( )

-

( )

Three dimensions

Index and symbol values

In three dimensions, when all i, j, k, m, n each take values 1, 2, and 3:[3]

-

( )

-

( )

-

( )

Tensor Calculus[7]

The Levi-Civita symbol resp. was already defined above in the identical Cartesian reference systems resp. as the permutation symbol through the skew-symmetric e-matrix resp. with numerical values . In the Cartesian system, it should continue to be denoted with Latin indices.

However, in the following, it is now transferred for tensor calculus into two dual, skewed, non-normalized reference systems with covariant basis vectors on one hand, and contravariant basis vectors on the other hand. Both reference systems are orthogonally aligned to each other through the identity matrix , and are always marked with Greek indices.

The transformation of tensor components between the Cartesian reference system and skewed reference systems [7] is done through the components of the contravariant basis vectors resp. the covariant basis vectors , where the orthogonality arises from the above relationship.

The determinant of the covariant metric tensor is obtained from the volume form with , and similarly, the determinant of the contravariant metric tensor is obtained from the volume form with .

As shown above, the Levi-Civita symbol in the Cartesian reference system can be obtained through the following determinant formation from

the Kronecker delta:

The -tensors in the skewed reference system are obtained through corresponding tensor transformations of the Levi-Civita symbol [7] or alternatively by multiplying the e-matrix by the volume element for both

the covariant -tensor: , and

the contravariant -tensor: .

Delta-Identities and Tensor Transformations[7]

The Levi-Civita symbol resp. -tensor is related to the Kronecker delta[4] by the Laplace expansion theorem. In three dimensions, this relationship is given by

with the -symbol of 6th order, representing the Lagrange identity.

By contraction of the last index, a special case follows from this identity as the Grassmann -identity with the Kronecker delta of 4th order

- ,

sometimes called as the "contracted epsilon identity".[8]

This relationship is e.g. useful in deriving further identities for the cross product

with

like the Lagrange identity with

- ,

or the Grassmann identity with

- ,

and the Jacobi identity with

- .

Further contractions of the Grassmann -identität result in the -identities

By use of according tensor transformations, the upper -identity may be used to determine the associated contravariant vector basis directly from a given covariant vector basis - just by rotation and normalization of the basis vectors - without any matrix inversion!

For this purpose the -identity of 2nd order is converted into the Meissner -identities[7] by several modifications as follow:

in : resp.

in : resp. .

Thus, approriate tensor transformations into the skewed reference system lead then, by some realignments and renamings of indices, to the contravariant Meissner tensorbasis transformations[7] for

the three-dimensional contravariant basis vectors

and the contravariant metric tensor ,

respectively to

the two-dimensional contravariant basis vectors

and the contravariant metric tensor .

For the numerical evaluation of tensor equations, specific tensor/matrix algorithms were developed based on object-oriented principles with documentation in details.[7] The associated C++ software with structured matrix and tensor classes implements the overloading of arithmetic and functional standard operators for the specific use of multi-dimensional tensor/matrix objects, incl. the generalized matrix multiplication . The program sources are available to the academic public and for private use over the WWW. [9]

n dimensions

Index and symbol values

In n dimensions, when all i1, ...,in, j1, ..., jn take values 1, 2, ..., n:

-

( )

-

( )

-

( )

where the exclamation mark (!) denotes the factorial, and δα...β... is the generalized Kronecker delta. For any n, the property

follows from the facts that

- every permutation is either even or odd,

- (+1)2 = (−1)2 = 1, and

- the number of permutations of any n-element set number is exactly n!.

The particular case of (8) with is

Product

In general, for n dimensions, one can write the product of two Levi-Civita symbols as: Proof: Both sides change signs upon switching two indices, so without loss of generality assume . If some then left side is zero, and right side is also zero since two of its rows are equal. Similarly for . Finally, if , then both sides are 1.

Proofs

For (1), both sides are antisymmetric with respect of ij and mn. We therefore only need to consider the case i ≠ j and m ≠ n. By substitution, we see that the equation holds for ε12ε12, that is, for i = m = 1 and j = n = 2. (Both sides are then one). Since the equation is antisymmetric in ij and mn, any set of values for these can be reduced to the above case (which holds). The equation thus holds for all values of ij and mn.

Here we used the Einstein summation convention with i going from 1 to 2. Next, (3) follows similarly from (2).

To establish (5), notice that both sides vanish when i ≠ j. Indeed, if i ≠ j, then one can not choose m and n such that both permutation symbols on the left are nonzero. Then, with i = j fixed, there are only two ways to choose m and n from the remaining two indices. For any such indices, we have

(no summation), and the result follows.

Then (6) follows since 3! = 6 and for any distinct indices i, j, k taking values 1, 2, 3, we have

- (no summation, distinct i, j, k)

Applications and examples

Determinants

In linear algebra, the determinant of a 3 × 3 square matrix A = [aij] can be written[10]

Similarly the determinant of an n × n matrix A = [aij] can be written as[5]

where each ir should be summed over 1, ..., n, or equivalently:

where now each ir and each jr should be summed over 1, ..., n. More generally, we have the identity[5]

Vector cross product

Cross product (two vectors)

Let a positively oriented orthonormal basis of a vector space. If (a1, a2, a3) and (b1, b2, b3) are the coordinates of the vectors a and b in this basis, then their cross product can be written as a determinant:[5]

hence also using the Levi-Civita symbol, and more simply:

In Einstein notation, the summation symbols may be omitted, and the ith component of their cross product equals[4]

The first component is

then by cyclic permutations of 1, 2, 3 the others can be derived immediately, without explicitly calculating them from the above formulae:

Triple scalar product (three vectors)

From the above expression for the cross product, we have:

- .

If c = (c1, c2, c3) is a third vector, then the triple scalar product equals

From this expression, it can be seen that the triple scalar product is antisymmetric when exchanging any pair of arguments. For example,

- .

Curl (one vector field)

If F = (F1, F2, F3) is a vector field defined on some open set of as a function of position x = (x1, x2, x3) (using Cartesian coordinates). Then the ith component of the curl of F equals[4]

which follows from the cross product expression above, substituting components of the gradient vector operator (nabla).

Tensor density

In any arbitrary curvilinear coordinate system and even in the absence of a metric on the manifold, the Levi-Civita symbol as defined above may be considered to be a tensor density field in two different ways. It may be regarded as a contravariant tensor density of weight +1 or as a covariant tensor density of weight −1. In n dimensions using the generalized Kronecker delta,[11][12]

Notice that these are numerically identical. In particular, the sign is the same.

Levi-Civita tensors

On a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, one may define a coordinate-invariant covariant tensor field whose coordinate representation agrees with the Levi-Civita symbol wherever the coordinate system is such that the basis of the tangent space is orthonormal with respect to the metric and matches a selected orientation. This tensor should not be confused with the tensor density field mentioned above. The presentation in this section closely follows Carroll 2004.

The covariant Levi-Civita tensor (also known as the Riemannian volume form) in any coordinate system that matches the selected orientation is

where gab is the representation of the metric in that coordinate system. We can similarly consider a contravariant Levi-Civita tensor by raising the indices with the metric as usual,

but notice that if the metric signature contains an odd number of negative eigenvalues q, then the sign of the components of this tensor differ from the standard Levi-Civita symbol:

where sgn(det[gab]) = (−1)q, and is the usual Levi-Civita symbol discussed in the rest of this article. More explicitly, when the tensor and basis orientation are chosen such that , we have that .

From this we can infer the identity,

where

is the generalized Kronecker delta.

Example: Minkowski space

In Minkowski space (the four-dimensional spacetime of special relativity), the covariant Levi-Civita tensor is

where the sign depends on the orientation of the basis. The contravariant Levi-Civita tensor is

The following are examples of the general identity above specialized to Minkowski space (with the negative sign arising from the odd number of negatives in the signature of the metric tensor in either sign convention):

See also

Notes

- ↑ Labelle, P. (2010). Supersymmetry. Demystified. McGraw-Hill. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-07-163641-4.

- ↑ Hadrovich, F.. "Twistor Primer". http://users.ox.ac.uk/~tweb/00004/index.shtml.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Tyldesley, J. R. (1973). An introduction to Tensor Analysis: For Engineers and Applied Scientists. Longman. ISBN 0-582-44355-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Kay, D. C. (1988). Tensor Calculus. Schaum's Outlines. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-033484-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Riley, K. F.; Hobson, M. P.; Bence, S. J. (2010). Mathematical Methods for Physics and Engineering. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86153-3. https://archive.org/details/mathematicalmeth00rile.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Permutation Symbol" (in en). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Meissner, Udo F. (2022). Tensorkalkül mit objektorientierten Matrizen für numerische Methoden in Mechanik und Ingenieurwesen. SpringerVieweg. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-39881-1. ISBN 978-3-658-39880-4.

- ↑ Herman. "The Levi-Civita Symbol". http://people.uncw.edu/hermanr/qm/Levi_Civita.pdf.

- ↑ Meissner, Udo F. (1995). "Object-oriented Tensor and Matrix Classes". https://Ing-Buero.Meissner.info/Tensor-Matrix-Klassen.

- ↑ Lipcshutz, S.; Lipson, M. (2009). Linear Algebra. Schaum's Outlines (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-154352-1.

- ↑ Murnaghan, F. D. (1925), "The generalized Kronecker symbol and its application to the theory of determinants", Amer. Math. Monthly 32 (5): 233–241, doi:10.2307/2299191

- ↑ Lovelock, David; Rund, Hanno (1989). Tensors, Differential Forms, and Variational Principles. Courier Dover Publications. p. 113. ISBN 0-486-65840-6.

References

- Misner, C.; Thorne, K. S.; Wheeler, J. A. (1973). Gravitation. W. H. Freeman & Co. pp. 85–86, §3.5. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Neuenschwander, D. E. (2015). Tensor Calculus for Physics. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 11, 29, 95. ISBN 978-1-4214-1565-9.

- Carroll, Sean M. (2004), Spacetime and Geometry, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-8053-8732-3, https://www.preposterousuniverse.com/spacetimeandgeometry/

External links

|