Medicine:Fibrochondrogenesis

| Fibrochondrogenesis | |

|---|---|

| |

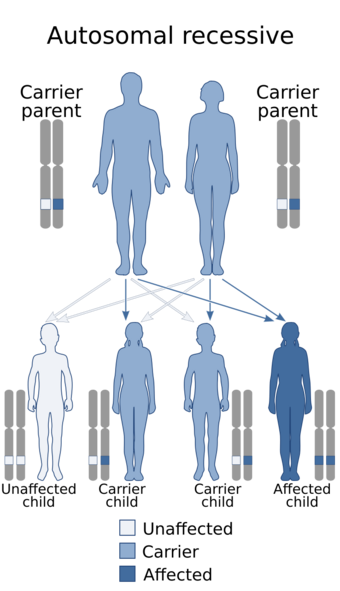

| Fibrochondrogenesis has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. |

Fibrochondrogenesis is a rare[1] autosomal recessive[2] form of osteochondrodysplasia,[3] causing abnormal fibrous development of cartilage and related tissues.[4]

It is a lethal rhizomelic (malformations which result in short, underdeveloped limbs) form of dwarfism,[1] exhibiting both skeletal dysplasia (malformations of bone) and fibroblastic dysplasia (abnormal development of fibroblasts, specialized cells that make up fibrous connective tissue, which plays a role in the formation of cellular structure and promotes healing of damaged tissues).[4][5][6] Death caused by complications of fibrochondrogenesis occurs in infancy.[6]

Presentation

Fibrochondrogenesis is a congenital disorder presenting several features and radiological findings, some which distinguish it from other osteochondrodysplasias.[7] These include: fibroblastic dysplasia and fibrosis of chondrocytes (cells which form cartilage);[4][5] and flared, widened long bone metaphyses (the portion of bone that grows during childhood).[6][8]

Other prominent features include dwarfism,[1] shortened ribs that have a concave appearance,[6] micrognathism (severely underdeveloped jaw),[7] macrocephaly (enlarged head),[8] thoracic hypoplasia (underdeveloped chest),[8] enlarged stomach,[8] platyspondyly (flattened spine),[6] and the somewhat uncommon deformity of bifid tongue (in which the tongue appears split, resembling that of a reptile).[7]

Cause

The cause of platyspondyly in fibrochondrogenesis can be attributed in part to odd malformations and structural flaws found in the vertebral bodies of the spinal column in affected infants.[4][6]

Fibrochondrogenesis alters the normal function of chondrocytes, fibroblasts, metaphyseal cells and others associated with cartilage, bone and connective tissues.[2][3][4] Overwhelming disorganization of cellular processes involved in the formation of cartilage and bone (ossification), in combination with fibroblastic degeneration of these cells, developmental errors and systemic skeletal malformations describes the severity of this lethal osteochondrodysplasia.[3][4][6][8]

Genetics

Fibrochondrogenesis is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern.[4] This means that the defective gene responsible for the disorder is located on an autosome, and two copies of the gene — one copy inherited from each parent — are required in order to be born with the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder each carry one copy of the defective gene, but usually do not experience any signs or symptoms of the disorder. Currently, no specific genetic mutation has been established as the cause of fibrochondrogenesis.[9]

Omphalocele is a congenital feature where the abdominal wall has an opening, partially exposing the abdominal viscera (typically, the organs of the gastrointestinal tract). Fibrochondrogenesis is believed to be related to omphalocele type III, suggesting a possible genetic association between the two disorders.[10]

Diagnosis

Treatment

Epidemiology

Fibrochondrogenesis is quite rare.[1] A 1996 study from Spain determined a national minimal prevalence for the disorder at 8 cases out of 1,158,067 live births.[11]

A United Arab Emirates (UAE) University report, from early 2003, evaluated the results of a 5-year study on the occurrence of a broad range of osteochondrodysplasias.[12] Out of 38,048 newborns in Al Ain, over the course of the study period, fibrochondrogenesis was found to be the most common of the recessive forms of osteochondrodysplasia, with a prevalence ratio of 1.05:10,000 births.[12]

While these results represented the most common occurrence within the group studied, they do not dispute the rarity of fibrochondrogenesis. The study also included the high rate of consanguinous marriages as a prevailing factor for these disorders, as well as the extremely low rate of diagnosis-related pregnancy terminations throughout the region.[12]

Research

The fibrocartilaginous effects of fibrochondrogenesis on chondrocytes has shown potential as a means to produce therapeutic cellular biomaterials via tissue engineering and manipulation of stem cells,[13][14] specifically human embryonic stem cells.[13]

Utilization of these cells as curative cartilage replacement materials on the cellular level has shown promise, with beneficial applications including the repair and healing of damaged knee menisci and synovial joints; temporomandibular joints, and vertebra.[13][14][15]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Fibrochondrogenesis". Indian J Pediatr. 72 (4): 355–357. Apr 2005. doi:10.1007/BF02724021. PMID 15876767.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Two sibs with fibrochondrogenesis". Am J Med Genet A 127 A (3): 318–320. Jun 2004. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20620. PMID 15150788.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Fetal fibrochondrogenesis at 26 weeks gestation". Prenat Diagn. 22 (9): 806–810. Sep 2002. doi:10.1002/pd.423. PMID 12224076.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Whitley CB et al. (1984). "Fibrochondrogenesis: lethal, autosomal recessive chondrodysplasia with distinctive cartilage histopathology". Am J Med Genet 19 (2): 265–275. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320190209. PMID 6507478.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Fibrochondrogenesis" (in French). Arch Fr Pediatr 35 (10): 1096–1104. 1978. PMID 749746.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 "Fibrochondrogenesis: radiologic and histologic studies". Am J Med Genet 19 (2): 277–290. 1984. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320190210. PMID 6507479.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Fibrochondrogenesis in a 17-week fetus: a case expanding the phenotype". American Journal of Medical Genetics 75 (3): 326–329. Jan 1998. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980123)75:3<326::AID-AJMG20>3.0.CO;2-Q. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 9475607.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Prenatal ultrasonography: clinical and radiological findings in a boy with fibrochondrogenesis". American Journal of Perinatology 15 (7): 403–407. Jul 1998. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993966. ISSN 0735-1631. PMID 9759906.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 282520

- ↑ Chen CP (Jan 2007). "Syndromes and disorders associated with omphalocele (III): single gene disorders, neural tube defects, diaphragmatic defects and others". Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 46 (2): 111–120. doi:10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60004-7. PMID 17638618.

- ↑ "A new case of fibrochondrogenesis from Spain". J Med Genet 33 (5): 429–431. May 1996. doi:10.1136/jmg.33.5.429. ISSN 0022-2593. PMID 8733059.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Birth prevalence and pattern of osteochondrodysplasias in an inbred high risk population". Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology 67 (2): 125–132. Feb 2003. doi:10.1002/bdra.10009. ISSN 1542-0752. PMID 12769508.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Fibrochondrogenesis of hESCs: Growth Factor Combinations and Cocultures". Stem Cells and Development 18 (2): 283–92. May 2008. doi:10.1089/scd.2008.0024. ISSN 1547-3287. PMID 18454697.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Fibrochondrogenesis in two embryonic stem cell lines: effects of differentiation timelines". Stem Cells 26 (2): 422–430. Feb 2008. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0641. ISSN 1066-5099. PMID 18032702.

- ↑ "Fibrochondrogenesis of free intraarticular small intestinal submucosa scaffolds". Tissue Engineering 10 (1–2): 129–37. Jan 2004. doi:10.1089/107632704322791772. ISSN 1076-3279. PMID 15009938.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|