Medicine:Rolandic epilepsy

| Rolandic epilepsy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS), self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes |

| |

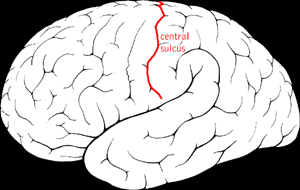

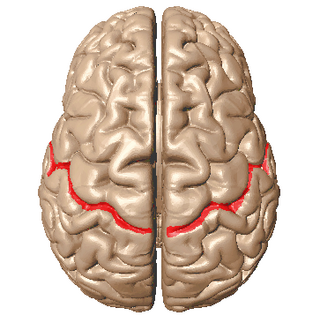

| Diagram showing the central sulcus of the brain. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Benign Rolandic epilepsy or self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (formerly benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)) is the most common epilepsy syndrome in childhood.[1][2] Most children will outgrow the syndrome (it starts around the age of 3–13 with a peak around 8–9 years and stops around age 14–18), hence the label benign.[3][4] The seizures, sometimes referred to as sylvian seizures, start around the central sulcus of the brain (also called the centrotemporal area, located around the Rolandic fissure, after Luigi Rolando).[5]

Signs and symptoms

The cardinal features of Rolandic epilepsy are infrequent, often single, focal seizures consisting of:[6][7][8][9][10][11]

- a. unilateral facial sensorimotor symptoms (30% of patients)

- b. oropharyngolaryngeal manifestations (53% of patients)

- c. speech arrest (40% of patients), and

- d. hypersalivation (30% of patients)

Hemifacial sensorimotor seizures are often entirely localised in the lower lip or spread to the ipsilateral hand. Motor manifestations are sudden, continuous or bursts of clonic contractions, usually lasting from a few seconds to a minute. Ipsilateral tonic deviation of the mouth is also common. Hemifacial sensory symptoms consist of unilateral numbness mainly in the corner of the mouth. Hemifacial seizures are often associated with an inability to speak and hypersalivation: The left side of my mouth felt numb and started jerking and pulling to the left, and I could not speak to say what was happening to me. Negative myoclonus can be observed in some cases, as an interruption of tonic muscular activity

Oropharyngolaryngeal ictal manifestations are unilateral sensorimotor symptoms inside the mouth. Numbness, and more commonly paraesthesias (tingling, prickling, freezing), are usually diffuse on one side or, exceptionally, may be highly localised even to one tooth. Motor oropharyngolaryngeal symptoms produce strange sounds, such as death rattle, gargling, grunting and guttural sounds, and combinations: In his sleep, he was making guttural noises, with his mouth pulled to the right, ‘as if he was chewing his tongue’. We heard her making strange noises ‘like roaring’ and found her unresponsive, head raised from the pillow, eyes wide open, rivers of saliva coming out of her mouth, rigid.

Arrest of speech is a form of anarthria. The child is unable to utter a single intelligible word and attempts to communicate with gestures. My mouth opened and I could not speak. I wanted to say I cannot speak. At the same time, it was as if somebody was strangling me.

Hypersalivation, a prominent autonomic manifestation, is often associated with hemifacial seizures, oro-pharyngo-laryngeal symptoms and speech arrest. Hypersalivation is not just frothing: Suddenly my mouth is full of saliva, it runs out like a river and I cannot speak.

Syncope-like epileptic seizures may occur, probably as a concurrent symptom of Panayiotopoulos syndrome: She lies there, unconscious with no movements, no convulsions, like a wax work, no life.

Consciousness and recollection are fully retained in more than half (58%) of Rolandic seizures. I felt that air was forced into my mouth, I could not speak and I could not close my mouth. I could understand well everything said to me. Other times I feel that there is food in my mouth and there is also a lot of salivation. I cannot speak. In the remainder (42%), consciousness becomes impaired during the ictal progress and in one third there is no recollection of ictal events.

Progression to hemiconvulsions or generalised tonic-clonic seizures occurs in around half of children and hemiconvulsions may be followed by postictal Todd's hemiparesis.

Duration and circadian distribution: Rolandic seizures are usually brief, lasting for 1–3 minutes. Three-quarters of seizures occur during nonrapid eye movement sleep, mainly at sleep onset or just before awakening.

Status epilepticus: Although rare, focal motor status or hemiconvulsive status epilepticus is more likely to occur than secondarily generalised convulsive status epilepticus, which is exceptional.[12][13] Opercular status epilepticus usually occurs in children with atypical evolution or may be induced by carbamazepine or lamotrigine. This state lasts for hours to months and consists of ongoing unilateral or bilateral contractions of the mouth, tongue or eyelids, positive or negative subtle perioral or other myoclonus, dysarthria, speech arrest, difficulties in swallowing, buccofacial apraxia and hypersalivation. These are often associated with continuous spikes and waves on an EEG during NREM sleep.

Other seizure types: Despite prominent hypersalivation, focal seizures with primarily autonomic manifestations (autonomic seizures) are not considered part of the core clinical syndrome of Rolandic epilepsy. However, some children may present with independent autonomic seizures or seizures with mixed Rolandic-autonomic manifestations including emesis as in Panayiotopoulos syndrome.[14][15][16][17]

Atypical forms: Rolandic epilepsy may present with atypical manifestations such early age at onset, developmental delay or learning difficulties at inclusion, other seizure types, atypical EEG abnormalities.[13][18][19][20]

These children usually have normal intelligence and development.[3] Learning can remain unimpaired while a child is afflicted with Rolandic epilepsy.

Cause

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes is thought to be a genetic disorder. An autosomal dominant inheritance with age dependency and variable penetrance has been reported, although not all studies support this theory.[4][21][22] Linkage studies have pointed to a possible susceptibility region on chromosome 15q14, in the vicinity of the alpha-7 subunit of the acetylcholine receptor.[23] Most studies show a slight male predominance.[4] Because of the benign course and age-specific occurrence, it is thought to represent a hereditary impairment of brain maturation.[4]

An association with ELP4 has been identified.[24]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be confirmed when the characteristic centrotemporal spikes are seen on electroencephalography (EEG).[25] Typically, high-voltage spikes followed by slow waves are seen.[26] Given the nocturnal activity, a sleep EEG can often be helpful. Technically, the label "benign" can only be confirmed if the child's development continues to be normal during follow-up.[4] Neuroimaging, usually with an MRI scan, is only advised for cases with atypical presentation or atypical findings on clinical examination or EEG. The disorder should be differentiated from several other conditions, especially centrotemporal spikes without seizures, centrotemporal spikes with local brain pathology, central spikes in Rett syndrome and fragile X syndrome, malignant Rolandic epilepsy, temporal lobe epilepsy and Landau-Kleffner syndrome.[citation needed]

Treatment

Given the benign nature of the condition and the low seizure frequency, treatment is often unnecessary. If treatment is warranted or preferred by the child and his or her family, antiepileptic drugs can usually control the seizures easily.[3] Carbamazepine is the most frequently used first-line drug, but many other antiepileptic drugs, including valproate, phenytoin, gabapentin, levetiracetam and sultiame have been found effective as well.[4] Bedtime dosing is advised by some.[27] Treatment can be short and drugs can almost certainly be discontinued after two years without seizures and with normal EEG findings, perhaps even earlier.[4] Parental education about Rolandic epilepsy is the cornerstone of correct management. The traumatizing, sometimes long-lasting effect on parents is significant.[28]

It is unclear if there are any benefits to clobazam over other seizure medications.[29]

Prognosis

The prognosis for Rolandic seizures is invariably excellent, with probably less than 2% risk of developing absence seizures and less often GTCS in adult life.[6][7][8][9][10][11] Remission usually occurs within 2–4 years from onset and before the age of 16 years. The total number of seizures is low, the majority of patients having fewer than 10 seizures; 10–20% have just a single seizure. About 10–20% may have frequent seizures, but these also remit with age. Children with Rolandic seizures may develop usually mild and reversible linguistic, cognitive and behavioural abnormalities during the active phase of the disease.[30][31][32][33] These may be worse in children with onset of seizures before 8 years of age, high rate of occurrence and multifocal EEG spikes.[34][35] The development, social adaptation and occupations of adults with a previous history of Rolandic seizures were found normal.[36][37]

Epidemiology

The age of onset ranges from 1 to 14 years with 75% starting between 7–10 years. There is a 1.5 male predominance, prevalence is around 15% in children aged 1–15 years with non-febrile seizures and incidence is 10–20/100,000 of children aged 0–15 years[38][39][40][41][42]

See also

References

- ↑ Ferrari-Marinho, Taissa; Hamad, Ana Paula Andrade; Casella, Erasmo Barbante; Yacubian, Elza Marcia Targas; Caboclo, Luis Otavio (September 2020). "Seizures in self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: video-EEG documentation". Child's Nervous System 36 (9): 1853–1857. doi:10.1007/s00381-020-04763-8. ISSN 1433-0350. PMID 32661641. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32661641/.

- ↑ Kramer U (July 2008). "Atypical presentations of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: a review". J. Child Neurol. 23 (7): 785–90. doi:10.1177/0883073808316363. PMID 18658078.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Wirrell EC (1998). "Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes". Epilepsia 39 Suppl 4: S32–41. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb05123.x. PMID 9637591.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Benign pediatric localization-related epilepsies". Epileptic Disord 8 (4): 243–58. December 2006. PMID 17150437. http://www.john-libbey-eurotext.fr/medline.md?issn=1294-9361&vol=8&iss=4&page=243.

- ↑ Benign Rolandic epilepsy. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Beaussart, Marc (December 1972). "Benign epilepsy of children with Rolandic (centro-temporal) paroxysmal foci. A clinical entity. Study of 221 cases.". Epilepsia 13 (6): 795–811. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1972.tb05164.x. PMID 4509173.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Loiseau, P; Beaussart, M (December 1973). "The seizures of benign childhood epilepsy with Rolandic paroxysmal discharges.". Epilepsia 14 (4): 381–389. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1973.tb03977.x. PMID 4521094.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lerman, P; Kivity, S (April 1975). "Benign focal epilepsy of childhood. A follow-up study of 100 recovered patients.". Archives of Neurology 32 (4): 261–264. doi:10.1001/archneur.1975.00490460077010. PMID 804895.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Panayiotopoulos, Chrysostomos P. (1 January 1999). "Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes or Rolandic seizures". Benign Childhood Partial Seizures and Related Epileptic Syndromes. London: John Libbey Eurotext. pp. 33–100. ISBN 978-0-86196-577-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=r4l7Jm_W0_sC. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dalla, Bernardina; Sgro, Vincenzo; Fejerman, Natalio (1 January 2005). "Epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes and related syndromes". Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence. France: John Libbey Eurotext. pp. 203–225. ISBN 978-2-7420-0569-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=tzah9qcyZZ8C&pg=PA203. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Panayiotopoulos, C. P.; Michael, M.; Sanders, S.; Valeta, T.; Koutroumanidis, M. (21 August 2008). "Benign childhood focal epilepsies: assessment of established and newly recognized syndromes". Brain 131 (9): 2264–2286. doi:10.1093/brain/awn162. PMID 18718967.

- ↑ "Combined myoclonic-astatic and "benign" focal epilepsy of childhood ("atypical benign partial epilepsy of childhood"). A separate syndrome?". Neuropediatrics 17 (3): 144–51. 1986. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1052516. PMID 3762871.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Fejerman, Natalio; Caraballo, Roberto; Tenembaum, Silvia N. (1 April 2000). "Atypical Evolutions of Benign Localization-Related Epilepsies in Children: Are They Predictable?". Epilepsia 41 (4): 380–390. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00177.x. PMID 10756401.

- ↑ MICHALIS KOUTROUMANIDIS; CHR YSOSTOMOS PANAYIOTOPOULOS. Chapter 9: Benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndromes. https://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Chapter09Koutroumanidis2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Panayiotopoulos syndrome: a prospective study of 192 patients". Epilepsia 48 (6): 1054–61. June 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01085.x. PMID 17442007.

- ↑ "Panayiotopoulos syndrome: A clinical, EEG, and neuropsychological study of 93 consecutive patients". Epilepsia 51 (10): 2098–107. October 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02639.x. PMID 20528983.

- ↑ "Chapter 9 Benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndromes". https://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Chapter09Koutroumanidis2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Benign epilepsy of childhood with rolandic spikes: typical and atypical variants". Pediatr Neurol 36 (3): 141–5. March 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.12.003. PMID 17352945.

- ↑ Kramer U (July 2008). "Atypical presentations of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: a review". J Child Neurol 23 (7): 785–90. doi:10.1177/0883073808316363. PMID 18658078.

- ↑ "Benign rolandic epilepsy: atypical features are very common". Journal of Child Neurology 10 (6): 455–8. 1995. doi:10.1177/088307389501000606. PMID 8576555.

- ↑ Neubauer BA (2000). "The genetics of rolandic epilepsy". Epileptic Disord 2 Suppl 1: S67–8. PMID 11231229. http://www.john-libbey-eurotext.fr/medline.md?issn=1294-9361&vol=2%20Suppl%201&iss=&page=S67.

- ↑ "Autosomal dominant inheritance of centrotemporal sharp waves in rolandic epilepsy families". Epilepsia 48 (12): 2266–72. December 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01221.x. PMID 17662063.

- ↑ "Centrotemporal spikes in families with rolandic epilepsy: linkage to chromosome 15q14". Neurology 51 (6): 1608–12. December 1998. doi:10.1212/WNL.51.6.1608. PMID 9855510.

- ↑ "Centrotemporal sharp wave EEG trait in rolandic epilepsy maps to Elongator Protein Complex 4 (ELP4)". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17 (9): 1171–1181. January 2009. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.267. PMID 19172991.

- ↑ Blueprints Neurology, 2nd ed.

- ↑ Stephani U (2000). "Typical semiology of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS)". Epileptic Disord 2 Suppl 1: S3–4. PMID 11231216. http://www.john-libbey-eurotext.fr/medline.md?issn=1294-9361&vol=2%20Suppl%201&iss=&page=S3.

- ↑ "A practical approach to uncomplicated seizures in children". Am Fam Physician 62 (5): 1109–16. September 2000. PMID 10997534.

- ↑ Valeta T. Parental attitude, reaction and education in benign childhood focal seizures. In: Panayiotopoulos CP, editor. The Epilepsies: Seizures, Syndromes and Management.Oxford: Bladon Medical Publishing; 2005. p. 258-61.

- ↑ Arya, Ravindra; Giridharan, Nisha; Anand, Vidhu; Garg, Sushil K. (2018). "Clobazam monotherapy for focal or generalized seizures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (7): CD009258. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009258.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 29995989.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological assessment of children with rolandic epilepsy: Executive functions". Epilepsy Behav 24 (4): 403–7. August 2012. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.131. PMID 22683244.

- ↑ "Long term outcome of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes: Dutch Study of Epilepsy in Childhood". Seizure 19 (8): 501–6. October 2010. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2010.07.007. PMID 20688544.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological aspects of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes". Seizure 19 (1): 12–6. January 2010. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2009.10.004. PMID 19963405.

- ↑ "Cognitive deficits in children with benign rolandic epilepsy of childhood or rolandic discharges: a study of children between 4 and 7 years of age with and without seizures compared with healthy controls". Epilepsy Behav 16 (4): 646–51. December 2009. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.012. PMID 19879197.

- ↑ "Academic performance in children with rolandic epilepsy". Dev Med Child Neurol 50 (5): 353–6. May 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02040.x. PMID 18294216.

- ↑ "Verbal dichotic listening performance and its relationship with EEG features in benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes". Epilepsy Res 79 (1): 31–8. March 2008. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.12.016. PMID 18294817.

- ↑ "Benign epilepsy of children with centrotemporal EEG foci: a follow-up study in adulthood of patients initially studied as children". Epilepsia 23 (6): 629–32. 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1982.tb05078.x. PMID 7173130.

- ↑ "Long-term prognosis in two forms of childhood epilepsy: typical absence seizures and epilepsy with rolandic (centrotemporal) EEG foci". Annals of Neurology 13 (6): 642–8. 1983. doi:10.1002/ana.410130610. PMID 6410975.

- ↑ "Prevalence and characteristics of epilepsy in children in northern Sweden". Seizure 5 (2): 139–46. 1996. doi:10.1016/s1059-1311(96)80055-0. PMID 8795130.

- ↑ "Rolandic epilepsy: an incidence study in Iceland". Epilepsia 39 (8): 884–6. August 1998. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01185.x. PMID 9701381.

- ↑ "The course of benign partial epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes: a meta-analysis". Neurology 48 (2): 430–7. 1997. doi:10.1212/wnl.48.2.430. PMID 9040734.

- ↑ "A population based study of epilepsy in children from a Swedish county". Eur J Paediatr Neurol 10 (3): 107–13. May 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.02.005. PMID 16638642.

- ↑ "Newly diagnosed epilepsy in children: presentation at diagnosis". Epilepsia 40 (4): 445–52. April 1999. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00739.x. PMID 10219270.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|