Medicine:Sentinel lymph node

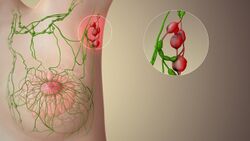

The sentinel lymph node is the hypothetical first lymph node or group of nodes draining a cancer. In case of established cancerous dissemination it is postulated that the sentinel lymph nodes are the target organs primarily reached by metastasizing cancer cells from the tumor.

The sentinel node procedure (also termed sentinel lymph node biopsy or SLNB) is the identification, removal and analysis of the sentinel lymph nodes of a particular tumour.[1]

Physiology

The spread of some forms of cancer usually follows an orderly progression, spreading first to regional lymph nodes, then the next echelon of lymph nodes, and so on, since the flow of lymph is directional, meaning that some cancers spread in a predictable fashion from where the cancer started. In these cases, if the cancer spreads it will spread first to lymph nodes (lymph glands) close to the tumor before it spreads to other parts of the body. The concept of sentinel lymph node surgery is to determine if the cancer has spread to the very first draining lymph node (called the "sentinel lymph node") or not. If the sentinel lymph node does not contain cancer, then there is a high likelihood that the cancer has not spread to any other area of the body.[2]

Uses

The concept of the sentinel lymph node is important because of the advent of the sentinel lymph node biopsy technique, also known as a sentinel node procedure. This technique is used in the staging of certain types of cancer to see if they have spread to any lymph nodes, since lymph node metastasis is one of the most important prognostic signs. It can also guide the surgeon to the appropriate therapy.[3]

There are various procedures entailing the sentinel node detection:

- Preoperative planar lymphoscintigraphy

- Preoperative planar lymphoscintigraphy in conjunction with SPECT/CT [single photonemission CT (SPECT) with a low-dose CT][4][5]

- Intraoperative visual blue dye detection

- Intraoperative fluorescence detection (fluorescence image-guided surgery)

- Intraoperative gamma probe/Geiger meter-detection

- Preoperative or intraoperative super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles injection, detection by using Sentimag instrument[6][7]

- Postoperative scintigraphy of main specimen with planar acquisition

In everyday clinical activity, entailing sentinel node detection and sentinel lymph node biopsy, it is not required to include all different techniques listed above. In skilled hands and in a center with sound routines, one, two or three of the listed methods can be considered sufficient.

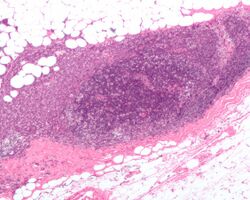

To perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy, the physician performs a lymphoscintigraphy, wherein a low-activity radioactive substance is injected near the tumor. The injected substance, filtered sulfur colloid, is tagged with the radionuclide technetium-99m. The injection protocols differ by doctor but the most common is a 500 μCi dose divided among 5 tuberculin syringes with 1/2 inch, 24 gauge needles.[citation needed] In the UK 20 megabecquerels of nanocolloid is recommended.[8] The sulphur colloid is slightly acidic and causes minor stinging. A gentle massage of the injection sites spreads the sulphur colloid, relieving the pain and speeding up the lymph uptake. Scintigraphic imaging is usually started within 5 minutes of injection and the node appears from 5 min to 1 hour. This is usually done several hours before the actual biopsy. About 15 minutes before the biopsy the physician injects a blue dye in the same manner. Then, during the biopsy, the physician visually inspects the lymph nodes for staining and uses a gamma probe or a Geiger counter to assess which lymph nodes have taken up the radionuclide. One or several nodes may take up the dye and radioactive tracer, and these nodes are designated the sentinel lymph nodes. The surgeon then removes these lymph nodes and sends them to a pathologist for rapid examination under a microscope to look for the presence of cancer.

A frozen section procedure is commonly employed (which takes less than 20 minutes), so if neoplasia is detected in the lymph node a further lymph node dissection may be performed. With malignant melanoma, many pathologists eschew frozen sections for more accurate "permanent" specimen preparation due to the increased instances of false-negative with melanocytic staining.

Clinical advantages

There are various advantages to the sentinel node procedure. First and foremost, it decreases lymph node dissections where unnecessary, thereby reducing the risk of lymphedema, a common complication of this procedure. Increased attention on the node(s) identified to most likely contain metastasis is also more likely to detect micrometastasis and result in staging and treatment changes. Its main uses are in breast cancer and malignant melanoma surgery, although it has been used in other tumor types (colon cancer) with a degree of success.[9] Other cancers which have been investigated with this technique are penile cancer, urinary bladder cancer,[10][11] prostate cancer,[12][13][14] testicular cancer[15][16] and renal cell cancer.[17][18]

Research advantages

As a bridge to translational medicine, various aspects of cancer dissemination can be studied using sentinel node detection and ensuing sentinel node biopsy. Tumor biology pertaining to metastatic capacity,[19] mechanisms of dissemination, the EMT-MET-process (epithelial–mesenchymal transition) and cancer immunology[20] are some subjects which can be more distinctly investigated.

Disadvantages

However, the technique is not without drawbacks, particularly when used for melanoma patients. This technique only has therapeutic value in patients with positive nodes.[21] Failure to detect cancer cells in the sentinel node can lead to a false negative result—there may still be cancerous cells in the lymph node basin. In addition, there is no compelling evidence that patients who have a full lymph node dissection as a result of a positive sentinel lymph node result have improved survival compared to those who do not have a full dissection until later in their disease, when the lymph nodes can be felt by a physician. Such patients may be having an unnecessary full dissection, with the attendant risk of lymphedema.[22]

History

The concept of a sentinel node was first described by Gould et al. 1960 in a patient with cancer of the parotid gland[23] and was implemented clinically on a broad scale by Cabanas in penile cancer.[24] The technique of sentinel node radiolocalization was co-founded by James C. Alex, MD, FACS and David N. Krag MD (University of Vermont Medical Center) and they were the first ones to pioneer this method for the use of cutaneous melanoma, breast cancer, head and neck cancer and Merkel cell carcinoma. Confirmative trials followed soon after.[25] Studies were also conducted at the Moffitt Cancer Center with Charles Cox, MD, Cristina Wofter, MD, Douglas Reintgen, MD and James Norman, MD. Following validation of the sentinel node biopsy technique, a number of randomised controlled trials were initiated to establish whether the technique could safely be used to avoid unnecessary axillary dissection among women with early breast cancer. The first such trial, led by Umberto Veronesi at the European Institute of Oncology, showed that women with breast tumours of 2 cm or less could safely forgo axillary dissection if their sentinel lymph nodes were found to be cancer-free on biopsy.[26] The benefits included less pain, greater arm mobility and less swelling in the arm.[27]

See also

- ALMANAC, Axillary Lymphatic Mapping Against Nodal Axillary Clearance trial

References

- ↑ "Malignant Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors and Role of SLNB". Journal of the American College of Surgeons 232 (6): 889–898. June 2021. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.01.019. PMID 33727135.

- ↑ "Sentinel-lymph-node procedures in early stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Medical Oncology 32 (1): 385. January 2015. doi:10.1007/s12032-014-0385-x. PMID 25429838.

- ↑ Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4377-2015-0.

- ↑ "Hybrid SPECT-CT: an additional technique for sentinel node detection of patients with invasive bladder cancer". European Urology 50 (1): 83–91. July 2006. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.03.002. PMID 16632191.

- ↑ "Anatomical mapping of lymphatic drainage in penile carcinoma with SPECT-CT: implications for the extent of inguinal lymph node dissection". European Urology 54 (4): 885–90. October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.04.094. PMID 18502024.

- ↑ "The Nordic SentiMag trial: a comparison of super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles versus Tc(99) and patent blue in the detection of sentinel node (SN) in patients with breast cancer and a meta-analysis of earlier studies". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 157 (2): 281–294. June 2016. doi:10.1007/s10549-016-3809-9. PMID 27117158.

- ↑ "Sentimag". Endomag. http://www.endomagnetics.com/sentimag.

- ↑ "Lymphoscintigraphy Clinical Guidelines". August 2011. http://www.bnms.org.uk/images/Lymphoscintigraphy_2016.pdf.

- ↑ "Frozen section investigation of the sentinel node in malignant melanoma and breast cancer". Annals of Surgical Oncology 8 (3): 222–6. April 2001. doi:10.1245/aso.2001.8.3.222. PMID 11314938.

- ↑ "Lymphatic mapping and detection of sentinel nodes in patients with bladder cancer". The Journal of Urology 166 (3): 812–5. September 2001. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65842-9. PMID 11490224.

- ↑ "Intraoperative sentinel node detection improves nodal staging in invasive bladder cancer". The Journal of Urology 175 (1): 84–8; discussion 88–9. January 2006. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00066-2. PMID 16406877.

- ↑ "The sentinel lymph node concept in prostate cancer - first results of gamma probe-guided sentinel lymph node identification". European Urology 36 (6): 595–600. December 1999. doi:10.1159/000020054. PMID 10559614.

- ↑ "Intensity modulated radiotherapy for high risk prostate cancer based on sentinel node SPECT imaging for target volume definition". BMC Cancer 5: 91. July 2005. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-5-91. PMID 16048656.

- ↑ "Detection of early lymph node metastases in prostate cancer by laparoscopic radioisotope guided sentinel lymph node dissection". The Journal of Urology 173 (6): 1943–6. June 2005. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000158159.16314.eb. PMID 15879787.

- ↑ "Lymphatic mapping and gamma probe guided laparoscopic biopsy of sentinel lymph node in patients with clinical stage I testicular tumor". The Journal of Urology 168 (4 Pt 1): 1390–5. October 2002. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64456-4. PMID 12352400.

- ↑ "SPECT/CT and a portable gamma-camera for image-guided laparoscopic sentinel node biopsy in testicular cancer". Journal of Nuclear Medicine 52 (4): 551–4. April 2011. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.086660. PMID 21421720.

- ↑ "Feasibility of sentinel node detection in renal cell carcinoma: a pilot study". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 37 (6): 1117–23. June 2010. doi:10.1007/s00259-009-1359-7. PMID 20111964.

- ↑ "Sentinel node detection in renal cell carcinoma. A feasibility study for detection of tumour-draining lymph nodes". BJU International 109 (8): 1134–9. April 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10444.x. PMID 21883833.

- ↑ "Early metastatic progression of bladder carcinoma: molecular profile of primary tumor and sentinel lymph node". The Journal of Urology 168 (5): 2240–4. November 2002. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64363-7. PMID 12394767.

- ↑ "Detection of immune responses against urinary bladder cancer in sentinel lymph nodes". European Urology 49 (1): 59–70. January 2006. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.09.010. PMID 16321468.

- ↑ Wagman LD. "Principles of Surgical Oncology" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach . 11 ed. 2008.

- ↑ "Prognostic false-positivity of the sentinel node in melanoma". Nature Clinical Practice. Oncology 5 (1): 18–23. January 2008. doi:10.1038/ncponc1014. PMID 18097453.

- ↑ "Observations on a "sentinel node" in cancer of the parotid". Cancer 13: 77–8. 1960. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(196001/02)13:1<77::aid-cncr2820130114>3.0.co;2-d. PMID 13828575.

- ↑ "An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma". Cancer 39 (2): 456–66. February 1977. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197702)39:2<456::aid-cncr2820390214>3.0.co;2-i. PMID 837331.

- ↑ "History of sentinel node and validation of the technique". Breast Cancer Research 3 (2): 109–12. 2001. doi:10.1186/bcr281. PMID 11250756.

- ↑ Veronesi, Umberto et al. (2006) Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol 7:983‒990 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70947-0

- ↑ Veronesi, Umberto et al. (2003) A Randomized Comparison of Sentinel-Node Biopsy with Routine Axillary Dissection in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 349:546-553 DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa012782

Further reading

- "Gamma-probe guided localization of lymph nodes". Surgical Oncology 2 (3): 137–43. 1993. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(93)90001-F. PMID 8252203.

- "Gamma-probe-guided lymph node localization in malignant melanoma". Surgical Oncology 2 (5): 303–8. October 1993. doi:10.1016/S0960-7404(06)80006-X. PMID 8305972.

- "Surgical resection and radiolocalization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe". Surgical Oncology 2 (6): 335–9; discussion 340. December 1993. doi:10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. PMID 8130940.

- "Minimal-access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma". Archives of Surgery 130 (6): 654–8; discussion 659–60. June 1995. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430060092018. PMID 7539252.

- "The gamma-probe-guided resection of radiolabeled primary lymph nodes". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America 5 (1): 33–41. January 1996. doi:10.1016/S1055-3207(18)30403-4. PMID 8789492.

- "Localization of regional lymph nodes in melanomas of the head and neck". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 124 (2): 135–40. February 1998. doi:10.1001/archotol.124.2.135. PMID 9485103.

- "The application of sentinel node radiolocalization to solid tumors of the head and neck: a 10-year experience". The Laryngoscope 114 (1): 2–19. January 2004. doi:10.1097/00005537-200401000-00002. PMID 14709988.

External links

- "Sentinel node biopsy using radiocolloid blue dye". You Tube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JtWk9brMRE.

- "Sentinel node biopsy". Cancer Management Handbook. August 11, 2011. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/diagnosis-staging/staging/sentinel-node-biopsy-fact-sheet.

- "Sentinel Lymph Node". Know Your Body. http://www.knowyourbody.net/sentinel-lymph-node.html.

- "International Sentinel Node Society (ISNS)". http://www.isns.info/main.php.

{{Navbox

| name = Tumors | title = Overview of tumors, cancer and oncology (C00–D48, 140–239) | state = autocollapse | listclass = hlist

| group1 = Conditions

| list1 =

| Benign tumors | |

|---|---|

| Malignant progression | |

| Topography | |

| Histology | |

| Other |

| group2 = Staging/grading | list2 =

| group3 = Carcinogenesis | list3 =

- Cancer cell

- Carcinogen

- [[Biology:Tumor suppressor Tumor suppressor genes/oncogenes

- Clonally transmissible cancer

- Oncovirus

- Carcinogenic bacteria

| group4 = Misc. | list4 =

}}