Medicine:Cancer research

Cancer research is research into cancer to identify causes and develop strategies for prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and cure.

Cancer research ranges from epidemiology, molecular bioscience to the performance of clinical trials to evaluate and compare applications of the various cancer treatments. These applications include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy and combined treatment modalities such as chemo-radiotherapy. Starting in the mid-1990s, the emphasis in clinical cancer research shifted towards therapies derived from biotechnology research, such as cancer immunotherapy and gene therapy.

Cancer research is done in academia, research institutes, and corporate environments, and is largely government funded.[citation needed]

History

Cancer research has been ongoing for centuries. Early research focused on the causes of cancer.[1] Percivall Pott identified the first environmental trigger (chimney soot) for cancer in 1775 and cigarette smoking was identified as a cause of lung cancer in 1950. Early cancer treatment focused on improving surgical techniques for removing tumors. Radiation therapy took hold in the 1900s. Chemotherapeutics were developed and refined throughout the 20th century.

The U.S. declared a "War on Cancer" in the 1970s, and increased the funding and support for cancer research.[2]

Seminal papers

Some of the most highly cited and most influential research reports include:

- The Hallmarks of Cancer, published in 2000, and Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation, published in 2011, by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg. Together, these articles have been cited in over 30,000 published papers.

Types of research

Cancer research encompasses a variety of types and interdisciplinary areas of research. Scientists involved in cancer research may be trained in areas such as chemistry, biochemistry, molecular biology, physiology, medical physics, epidemiology, and biomedical engineering. Research performed on a foundational level is referred to as basic research and is intended to clarify scientific principles and mechanisms. Translational research aims to elucidate mechanisms of cancer development and progression and transform basic scientific findings into concepts that can be applicable to the treatment and prevention of cancer. Clinical research is devoted to the development of pharmaceuticals, surgical procedures, and medical technologies for the eventual treatment of patients.

Prevention and epidemiology

Epidemiologic analysis indicates that at least 35% of all cancer deaths in the world could now be avoided by primary prevention.[3] According to a newer GBD systematic analysis, in 2019, ~44% of all cancer deaths – or ~4.5 M deaths or ~105 million lost disability-adjusted life years – were due to known clearly preventable risk factors, led by smoking, alcohol use and high BMI.[4]

However, one 2015 study suggested that between ~70% and ~90% of cancers are due to environmental factors and therefore potentially preventable.[5][contradictory] Furthermore, it is estimated that with further research cancer death rates could be reduced by 70% around the world even without the development of any new therapies.[3] Cancer prevention research receives only 2 to 9% of global cancer research funding,[3] albeit many of the options for prevention are already well-known without further cancer-specific research but are not reflected in economics and policy. Mutational signatures of various cancers, for example, could reveal further causes of cancer and support causal attribution.[6][additional citation(s) needed]

Detection

Prompt detection of cancer is important, since it is usually more difficult to treat in later stages. Accurate detection of cancer is also important because false positives can cause harm from unnecessary medical procedures. Some screening protocols are currently not accurate (such as prostate-specific antigen testing). Others such as a colonoscopy or mammogram are unpleasant and as a result some patients may opt out. Active research is underway to address all these problems, to develop novel ways of cancer screening and to increase detection rates.[citation needed][further explanation needed]

For example:

- Multimodal learning AI systems are being developed to help detect many cancer types via integrating different types of data.[7][8]

- Scientists work on identifying and measurability of novel biomarkers or sets of such to detect cancer early, such as tumor-associated mycobiomes and bacterial microbiomes[9][10][11][further explanation needed][additional citation(s) needed]

- Researchers investigate whether ants could be used as biosensors to detect cancer via urine[12][additional citation(s) needed]

Treatment

Emerging topics of cancer treatment research include:

- Anti-cancer vaccines

- Oncophage[13]

- Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is a prostate cancer vaccine

- Inactivated tumor cells are investigated as potential bifunctional cancer vaccines[14]

- Newer forms of chemotherapy

- Gene therapy[15][16][17]

- Photodynamic therapy

- Radiation therapy

- Reoviridae (Reolysin drug therapy)

- Targeted therapy

- Medical microbots (including bacterial),[18][19] nanobots[20] and bacterial 'cyborg cells'[21][additional citation(s) needed]

- Virotherapy[22][23]

- Antibodies[24][25][26][27][additional citation(s) needed]

- Photoimmunotherapy (for brain cancer)[28]Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag - How treatments can best be combined (in combination therapies)[29]

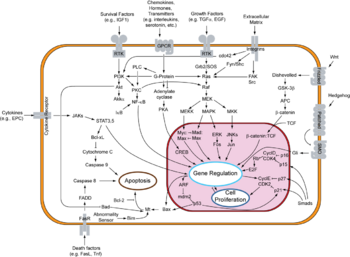

Cause and development of cancer

Research into the cause of cancer involves many different disciplines including genetics, diet, environmental factors (i.e. chemical carcinogens). In regard to investigation of causes and potential targets for therapy, the route used starts with data obtained from clinical observations, enters basic research, and, once convincing and independently confirmed results are obtained, proceeds with clinical research, involving appropriately designed trials on consenting human subjects, with the aim to test safety and efficiency of the therapeutic intervention method. An important part of basic research is characterization of the potential mechanisms of carcinogenesis, in regard to the types of genetic and epigenetic changes that are associated with cancer development. The mouse is often used as a mammalian model for manipulation of the function of genes that play a role in tumor formation, while basic aspects of tumor initiation, such as mutagenesis, are assayed on cultures of bacteria and mammalian cells.

Genes involved in cancer

The goal of oncogenomics is to identify new oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes that may provide new insights into cancer diagnosis, predicting clinical outcome of cancers, and new targets for cancer therapies. As the Cancer Genome Project stated in a 2004 review article, "a central aim of cancer research has been to identify the mutated genes that are causally implicated in oncogenesis (cancer genes)."[30] The Cancer Genome Atlas project is a related effort investigating the genomic changes associated with cancer, while the COSMIC cancer database documents acquired genetic mutations from hundreds of thousands of human cancer samples.[31]

These large scale projects, involving about 350 different types of cancer, have identified ~130,000 mutations in ~3000 genes that have been mutated in the tumours. The majority occurred in 319 genes, of which 286 were tumour suppressor genes and 33 oncogenes.

Several hereditary factors can increase the chance of cancer-causing mutations, including the activation of oncogenes or the inhibition of tumor suppressor genes. The functions of various onco- and tumor suppressor genes can be disrupted at different stages of tumor progression. Mutations in such genes can be used to classify the malignancy of a tumor.

In later stages, tumors can develop a resistance to cancer treatment. The identification of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes is important to understand tumor progression and treatment success. The role of a given gene in cancer progression may vary tremendously, depending on the stage and type of cancer involved.[32]

Cancer epigenetics

Cancer growth

Diet and cancer

Periods of intermittent fasting (time-restricted feeding which may not include caloric restriction) is investigated for potential usefulness in cancer prevention and treatment and as of 2021 additional trials are needed to elucidate the risks and benefits.[33][34][35][36] In some cases, "caloric restrictions could hinder both cancer growth and progression, besides enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiation therapy".[37] Caloric restriction mimetics, including some present in foods like spermidine, are also investigated for these or similar reasons.[38][39] Such and similar dietary supplements may contribute to prevention or treatment, with candidate substances including apigenin,[40][41][42] berberine,[43][44][45][46][47] jiaogulan,[48] and rhodiola rosea.[49][50]

Research funding

Cancer research is funded by government grants, charitable foundations and pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.[51]

In the early 2000s, most funding for cancer research came from taxpayers and charities, rather than from corporations. In the US, less than 30% of all cancer research was funded by commercial researchers such as pharmaceutical companies.[52] Per capita, public spending on cancer research by taxpayers and charities in the US was five times as much in 2002–03 as public spending by taxpayers and charities in the 15 countries that were full members of the European Union.[52] As a percentage of GDP, the non-commercial funding of cancer research in the US was four times the amount dedicated to cancer research in Europe.[52] Half of Europe's non-commercial cancer research is funded by charitable organizations.[52]

The National Cancer Institute is the major funding institution in the United States. In the 2016 fiscal year, the NCI funded $5.2 billion in cancer research.[53]

Difficulties

Difficulties inherent to cancer research are shared with many types of biomedical research.

Cancer research processes have been criticised. These include, especially in the US, for the financial resources and positions required to conduct research. Other consequences of competition for research resources appear to be a substantial number of research publications whose results cannot be replicated.[54][55][56][57]

Replicability

Public participation

Distributed computing

One can share computer time for distributed cancer research projects like Help Conquer Cancer.[63] World Community Grid also had a project called Help Defeat Cancer. Other related projects include the Folding@home and Rosetta@home projects, which focus on groundbreaking protein folding and protein structure prediction research. Vodafone has also partnered with the Garvan Institute to create the DreamLab Project, which uses distributed computing via an app on cellphones to perform cancer research.

Clinical trials

Members of the public can also join clinical trials as healthy control subjects or for methods of cancer detection.

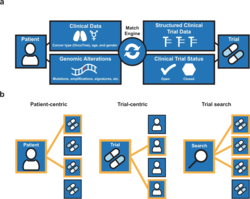

There could be software and data-related procedures that increase participation in trials and make them faster and less expensive. One open source platform matches genomically profiled cancer patients to precision medicine drug trials.[65][64]

Organizations

Organizations exist as associations for scientists participating in cancer research, such as the American Association for Cancer Research and American Society of Clinical Oncology, and as foundations for public awareness or raising funds for cancer research, such as Relay For Life and the American Cancer Society.

Awareness campaigns

Supporters of different types of cancer have adopted different colored awareness ribbons and promote months of the year as being dedicated to the support of specific types of cancer.[66] The American Cancer Society began promoting October as Breast Cancer Awareness Month in the United States in the 1980s. Pink products are sold to both generate awareness and raise money to be donated for research purposes. This has led to pinkwashing, or the selling of ordinary products turned pink as a promotion for the company.

See also

- .cancerresearch

- Exposome

References

- ↑ "Early Theories about Cancer Causes – American Cancer Society". https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/history-of-cancer/cancer-causes-theories-throughout-history.html.

- ↑ "Milestone (1971): President Nixon declares war on cancer". https://dtp.cancer.gov/timeline/flash/milestones/M4_Nixon.htm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Song M, Vogelstein B, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, Tomasetti C. Cancer prevention: Molecular and epidemiologic consensus. Science. 2018 Sep 28;361(6409):1317–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.aau3830. PMID 30262488; PMCID: PMC6260589

- ↑ Tran, Khanh BaoExpression error: Unrecognized word "et". (20 August 2022). "The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–19: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019" (in English). The Lancet 400 (10352): 563–591. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01438-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 35988567.

- ↑ "Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development". Nature 529 (7584): 43–7. January 2016. doi:10.1038/nature16166. PMID 26675728. Bibcode: 2016Natur.529...43W.

- ↑ Degasperi, AndreaExpression error: Unrecognized word "et". (22 April 2022). "Substitution mutational signatures in whole-genome–sequenced cancers in the UK population" (in en). Science 376 (6591): abl9283. doi:10.1126/science.abl9283. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35949260.

- University press release: "Largest study of whole genome sequencing data reveals 'treasure trove' of clues about causes of cancer" (in en). University of Cambridge. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2022-04-largest-genome-sequencing-reveals-treasure.html.

- ↑ Script error: No such module "cite news".

- ↑ Chen, Richard J.; Lu, Ming Y.; Williamson, Drew F. K.; Chen, Tiffany Y.; Lipkova, Jana; Noor, Zahra; Shaban, Muhammad; Shady, Maha et al. (8 August 2022). "Pan-cancer integrative histology-genomic analysis via multimodal deep learning" (in English). Cancer Cell 40 (8): 865–878.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2022.07.004. ISSN 1535-6108. PMID 35944502.

- Teaching hospital press release: "New AI technology integrates multiple data types to predict cancer outcomes" (in en). Brigham and Women's Hospital via medicalxpress.com. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2022-08-ai-technology-multiple-cancer-outcomes.html.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (29 September 2022). "A New Approach to Spotting Tumors: Look for Their Microbes". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/29/science/cancer-tumors-fungi-bacteria-microbiome.html.

- ↑ Dohlman, Anders B.; Klug, Jared; Mesko, Marissa; Gao, Iris H.; Lipkin, Steven M.; Shen, Xiling; Iliev, Iliyan D. (29 September 2022). "A pan-cancer mycobiome analysis reveals fungal involvement in gastrointestinal and lung tumors" (in English). Cell 185 (20): 3807–3822.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.015. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 36179671.

- ↑ Narunsky-Haziza, Lian; Sepich-Poore, Gregory D.; Livyatan, Ilana; Asraf, Omer; Martino, Cameron; Nejman, Deborah; Gavert, Nancy; Stajich, Jason E. et al. (29 September 2022). "Pan-cancer analyses reveal cancer-type-specific fungal ecologies and bacteriome interactions" (in English). Cell 185 (20): 3789–3806.e17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.005. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 36179670.

- ↑ Piqueret, Baptiste; Montaudon, Élodie; Devienne, Paul; Leroy, Chloé; Marangoni, Elisabetta; Sandoz, Jean-Christophe; d'Ettorre, Patrizia (25 January 2023). "Ants act as olfactory bio-detectors of tumours in patient-derived xenograft mice" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 290 (1991): 20221962. doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.1962. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 36695032.

- ↑ "Oncophage: step to the future for vaccine therapy in melanoma". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 8 (12): 1973–84. December 2008. doi:10.1517/14712590802517970. PMID 18990084.

- ↑ Chen, Kok-Siong; Reinshagen, Clemens; Van Schaik, Thijs A.; Rossignoli, Filippo; Borges, Paulo; Mendonca, Natalia Claire; Abdi, Reza; Simon, Brennan et al. (4 January 2023). "Bifunctional cancer cell–based vaccine concomitantly drives direct tumor killing and antitumor immunity" (in en). Science Translational Medicine 15 (677): eabo4778. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abo4778. ISSN 1946-6234. PMID 36599004.

- ↑ "Gene Therapy, Cancer-Killing Viruses And New Drugs Highlight Novel Approaches To Cancer Treatment". Medical News Today. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=68204.

- ↑ "World first gene therapy trial for leukaemia". LLR. http://leukaemialymphomaresearch.org.uk/research/achievements/new-treatments-blood-cancers.

- ↑ Chinese scientists to pioneer first human CRISPR trial

- ↑ Schmidt, Christine K.; Medina-Sánchez, Mariana; Edmondson, Richard J.; Schmidt, Oliver G. (5 November 2020). "Engineering microrobots for targeted cancer therapies from a medical perspective" (in en). Nature Communications 11 (1): 5618. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19322-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 33154372. Bibcode: 2020NatCo..11.5618S.

- ↑ Gwisai, T.; Mirkhani, N.; Christiansen, M. G.; Nguyen, T. T.; Ling, V.; Schuerle, S. (26 October 2022). "Magnetic torque–driven living microrobots for increased tumor infiltration" (in en). Science Robotics 7 (71): eabo0665. doi:10.1126/scirobotics.abo0665. ISSN 2470-9476. PMID 36288270.

- ↑ Kishore, Chandra; Bhadra, Priyanka (July 2021). "Targeting Brain Cancer Cells by Nanorobot, a Promising Nanovehicle: New Challenges and Future Perspectives". CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets 20 (6): 531–539. doi:10.2174/1871527320666210526154801. PMID 34042038.

- ↑ Contreras-Llano, Luis E.; Liu, Yu-Han; Henson, Tanner; Meyer, Conary C.; Baghdasaryan, Ofelya; Khan, Shahid; Lin, Chi-Long; Wang, Aijun et al. (11 January 2023). "Engineering Cyborg Bacteria Through Intracellular Hydrogelation" (in en). Advanced Science 10 (9): 2204175. doi:10.1002/advs.202204175. ISSN 2198-3844. PMID 36628538.

- News report about the study: Firtina, Nergis (1 February 2023). "Semi-living 'cyborg cells' could treat cancer, suggests new study". Interesting Engineering. https://interestingengineering.com/health/semi-living-cyborg-cells-treat-cancer.

- ↑ Lawler, Sean E.; Speranza, Maria-Carmela; Cho, Choi-Fong; Chiocca, E. Antonio (1 June 2017). "Oncolytic Viruses in Cancer Treatment: A Review". JAMA Oncology 3 (6): 841–849. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2064. PMID 27441411.

- ↑ Harrington, Kevin; Freeman, Daniel J.; Kelly, Beth; Harper, James; Soria, Jean-Charles (September 2019). "Optimizing oncolytic virotherapy in cancer treatment" (in en). Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 18 (9): 689–706. doi:10.1038/s41573-019-0029-0. ISSN 1474-1784. PMID 31292532.

- ↑ Osborne, Margaret. "Small Cancer Trial Resulted in Complete Remission for All Participants" (in en). Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/small-cancer-trial-resulted-in-complete-remission-for-all-participants-180980221/.

- ↑ Cercek, Andrea; Lumish, Melissa; Sinopoli, Jenna; Weiss, Jill; Shia, Jinru; Lamendola-Essel, Michelle; El Dika, Imane H.; Segal, Neil et al. (23 June 2022). "PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair–Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer". New England Journal of Medicine 386 (25): 2363–2376. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201445. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 35660797.

- ↑ "Trastuzumab Deruxtecan Leads to Longer PFS and OS Compared with Chemotherapy in Previously Treated HER2-Low Unresectable or Metastatic Breast Cancer". www.esmo.org. https://www.esmo.org/oncology-news/trastuzumab-deruxtecan-leads-to-longer-pfs-and-os-compared-with-chemotherapy-in-previously-treated-her2-low-unresectable-or-metastatic-breast-cancer.

- ↑ Modi, Shanu; Jacot, William; Yamashita, Toshinari; Sohn, Joohyuk; Vidal, Maria; Tokunaga, Eriko; Tsurutani, Junji; Ueno, Naoto T. et al. (5 June 2022). "Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer" (in en). New England Journal of Medicine 387 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2203690. PMID 35665782. PMC 10561652. https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/en/publications/4095995e-3067-46c9-875a-a70cdb641427.

- ↑ "Scientists harness light therapy to target and kill cancer cells in world first". The Guardian. 17 June 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jun/17/scientists-harness-light-therapy-to-target-and-kill-cancer-cells-in-world-first.

- ↑ Zhu, Shaoming; Zhang, Tian; Zheng, Lei; Liu, Hongtao; Song, Wenru; Liu, Delong; Li, Zihai; Pan, Chong-xian (December 2021). "Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy". Journal of Hematology & Oncology 14 (1): 156. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01164-5. PMID 34579759.

- ↑ "A census of human cancer genes". Nature Reviews. Cancer 4 (3): 177–183. March 2004. doi:10.1038/nrc1299. PMID 14993899.

- ↑ "COSMIC 2005". British Journal of Cancer 94 (2): 318–322. January 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602928. PMID 16421597.

- ↑ Vlahopoulos SA, Logotheti S, Mikas D, Giarika A, Gorgoulis V, Zoumpourlis V.The role of ATF-2 in oncogenesis" Bioessays 2008 Apr;30(4) 314-27.

- ↑ Clifton, Katherine K.; Ma, Cynthia X.; Fontana, Luigi; Peterson, Lindsay L. (November 2021). "Intermittent fasting in the prevention and treatment of cancer" (in en). CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71 (6): 527–546. doi:10.3322/caac.21694. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 34383300.

- ↑ Manoogian, Emily N. C.; Panda, Satchidananda (1 October 2017). "Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging" (in en). Ageing Research Reviews 39: 59–67. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.006. ISSN 1568-1637. PMID 28017879.

- ↑ Brandhorst, Sebastian; Longo, Valter D. (2016). "Fasting and Caloric Restriction in Cancer Prevention and Treatment" (in en). Metabolism in Cancer. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 207. Springer International Publishing. 241–266. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-42118-6_12. ISBN 978-3-319-42116-2.

- ↑ Alidadi, Mona; Banach, Maciej; Guest, Paul C.; Bo, Simona; Jamialahmadi, Tannaz; Sahebkar, Amirhossein (1 August 2021). "The effect of caloric restriction and fasting on cancer" (in en). Seminars in Cancer Biology 73: 30–44. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.09.010. ISSN 1044-579X. PMID 32977005.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Ezzeldin M.; Al-Foheidi, Meteb H.; Al-Mansour, Mubarak M. (1 May 2021). "Energy and caloric restriction, and fasting and cancer: a narrative review" (in en). Supportive Care in Cancer 29 (5): 2299–2304. doi:10.1007/s00520-020-05879-y. ISSN 1433-7339. PMID 33190181.

- ↑ Hofer, Sebastian J.; Davinelli, Sergio; Bergmann, Martina; Scapagnini, Giovanni; Madeo, Frank (2021). "Caloric Restriction Mimetics in Nutrition and Clinical Trials". Frontiers in Nutrition 8: 717343. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.717343. ISSN 2296-861X. PMID 34552954.

- ↑ Madeo, Frank; Eisenberg, Tobias; Pietrocola, Federico; Kroemer, Guido (26 January 2018). "Spermidine in health and disease" (in en). Science 359 (6374): eaan2788. doi:10.1126/science.aan2788. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29371440.

- ↑ Imran, Muhammad; Aslam Gondal, Tanweer; Atif, Muhammad; Shahbaz, Muhammad; Batool Qaisarani, Tahira; Hanif Mughal, Muhammad; Salehi, Bahare; Martorell, Miquel et al. (August 2020). "Apigenin as an anticancer agent" (in en). Phytotherapy Research 34 (8): 1812–1828. doi:10.1002/ptr.6647. ISSN 0951-418X. PMID 32059077.

- ↑ Shukla, Sanjeev; Gupta, Sanjay (1 June 2010). "Apigenin: A Promising Molecule for Cancer Prevention" (in en). Pharmaceutical Research 27 (6): 962–978. doi:10.1007/s11095-010-0089-7. ISSN 1573-904X. PMID 20306120.

- ↑ Shankar, Eswar; Goel, Aditi; Gupta, Karishma; Gupta, Sanjay (1 December 2017). "Plant Flavone Apigenin: an Emerging Anticancer Agent" (in en). Current Pharmacology Reports 3 (6): 423–446. doi:10.1007/s40495-017-0113-2. ISSN 2198-641X. PMID 29399439.

- ↑ Samadi, Parisa; Sarvarian, Parisa; Gholipour, Elham; Asenjan, Karim Shams; Aghebati-Maleki, Leili; Motavalli, Roza; Hojjat-Farsangi, Mohammad; Yousefi, Mehdi (October 2020). "Berberine: A novel therapeutic strategy for cancer" (in en). IUBMB Life 72 (10): 2065–2079. doi:10.1002/iub.2350. ISSN 1521-6543. PMID 32735398.

- ↑ Zhong, Xiao-Dan; Chen, Li-Juan; Xu, Xin-Yang; Liu, Yan-Jun; Tao, Fan; Zhu, Ming-Hui; Li, Chang-Yun; Zhao, Dan et al. (2022). "Berberine as a potential agent for breast cancer therapy". Frontiers in Oncology 12: 993775. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.993775. ISSN 2234-943X. PMID 36119505.

- ↑ Wang, Ye; Liu, Yanfang; Du, Xinyang; Ma, Hong; Yao, Jing (30 January 2020). "The Anti-Cancer Mechanisms of Berberine: A Review" (in English). Cancer Management and Research 12: 695–702. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S242329. PMID 32099466.

- ↑ Vlavcheski, Filip; O’Neill, Eric J.; Gagacev, Filip; Tsiani, Evangelia (January 2022). "Effects of Berberine against Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer" (in en). Molecules 27 (23): 8630. doi:10.3390/molecules27238630. ISSN 1420-3049. PMID 36500723.

- ↑ Guamán Ortiz, Luis Miguel; Lombardi, Paolo; Tillhon, Micol; Scovassi, Anna Ivana (August 2014). "Berberine, an Epiphany Against Cancer" (in en). Molecules 19 (8): 12349–12367. doi:10.3390/molecules190812349. ISSN 1420-3049. PMID 25153862.

- ↑ Su, Chao; Li, Nan; Ren, Ruru; Wang, Yingli; Su, Xiaojuan; Lu, Fangfang; Zong, Rong; Yang, Lingling et al. (January 2021). "Progress in the Medicinal Value, Bioactive Compounds, and Pharmacological Activities of Gynostemma pentaphyllum" (in en). Molecules 26 (20): 6249. doi:10.3390/molecules26206249. ISSN 1420-3049. PMID 34684830.

- ↑ Pu, Wei-ling; Zhang, Meng-ying; Bai, Ru-yu; Sun, Li-kang; Li, Wen-hua; Yu, Ying-li; Zhang, Yue; Song, Lei et al. (1 January 2020). "Anti-inflammatory effects of Rhodiola rosea L.: A review" (in en). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 121: 109552. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109552. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 31715370.

- ↑ Magani, Sri Krishna Jayadev; Mupparthi, Sri Durgambica; Gollapalli, Bhanu Prakash; Shukla, Dhananjay; Tiwari, A. K.; Gorantala, Jyotsna; Yarla, Nagendra Sastry; Tantravahi, Srinivasan (2020). "Salidroside - Can it be a Multifunctional Drug?" (in en). Current Drug Metabolism 21 (7): 512–524. doi:10.2174/1389200221666200610172105. PMID 32520682.

- ↑ "Federally Funded Cancer Research". 8 February 2016. https://www.asco.org/advocacy-policy/policies-positions-guidance/federally-funded-cancer-research.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 "A survey of public funding of cancer research in the European union". PLOS Medicine 3 (7): e267. July 2006. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030267. PMID 16842021.

- ↑ "Funding Trends" (in en). https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/budget/fact-book/historical-trends/funding.

- ↑ "Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (16): 5773–7. April 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1404402111. PMID 24733905. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111.5773A.

- ↑ "Advances Elusive in the Drive to Cure Cancer". The New York Times. 23 April 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/24/health/policy/24cancer.html.

- ↑ "Grant System Leads Cancer Researchers to Play It Safe". The New York Times. 27 June 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/28/health/research/28cancer.html.

- ↑ "Why We're Losing The War on Cancer". Fortune Magazine (CNN Money). 22 March 2004. https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2004/03/22/365076/index.htm.

- ↑ "Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research". Nature 483 (7391): 531–533. March 2012. doi:10.1038/483531a. PMID 22460880. Bibcode: 2012Natur.483..531B. (Erratum: doi:10.1038/485041e)

- ↑ "Dozens of major cancer studies can't be replicated". Science News. 7 December 2021. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cancer-biology-studies-research-replication-reproducibility.

- ↑ "Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology" (in en). Center for Open Science. https://www.cos.io/rpcb.

- ↑ "A survey on data reproducibility in cancer research provides insights into our limited ability to translate findings from the laboratory to the clinic". PLOS ONE 8 (5). 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063221. PMID 23691000. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...863221M.

- ↑ "Medicine is plagued by untrustworthy clinical trials. How many studies are faked or flawed?". Nature 619 (7970): 454–458. July 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02299-w. PMID 37464079. Bibcode: 2023Natur.619..454V.

- ↑ "Help Conquer Cancer". 19 November 2007. http://www.worldcommunitygrid.org/projects_showcase/hcc1/viewHcc1Main.do.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Klein, Harry; Mazor, Tali; Siegel, Ethan; Trukhanov, Pavel; Ovalle, Andrea; Vecchio Fitz, Catherine Del; Zwiesler, Zachary; Kumari, Priti et al. (6 October 2022). "MatchMiner: an open-source platform for cancer precision medicine" (in en). npj Precision Oncology 6 (1): 69. doi:10.1038/s41698-022-00312-5. ISSN 2397-768X. PMID 36202909.

- ↑ "Researchers report genomic profiling from more than 110,000 tumors" (in en). News-Medical.net. 19 July 2022. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20220719/Researchers-report-genomic-profiling-from-more-than-110000-tumors.aspx.

- ↑ "Cancer Awareness Dates". 19 December 2013. https://www.cancer.net/research-and-advocacy/cancer-awareness-dates.

External links

- Cancer Genome Anatomy Project @ The NIH

- The Integrative Cancer Biology Program @ National Cancer Institute

{{Navbox

| name = Tumors | title = Overview of tumors, cancer and oncology (C00–D48, 140–239) | state = autocollapse | listclass = hlist

| group1 = Conditions

| list1 =

| Benign tumors | |

|---|---|

| Malignant progression | |

| Topography | |

| Histology | |

| Other |

| group2 = Staging/grading | list2 =

| group3 = Carcinogenesis | list3 =

- Cancer cell

- Carcinogen

- [[Biology:Tumor suppressor Tumor suppressor genes/oncogenes

- Clonally transmissible cancer

- Oncovirus

- Carcinogenic bacteria

| group4 = Misc. | list4 =

}}

|