Medicine:Sexuality after spinal cord injury

Although spinal cord injury (SCI) often causes sexual dysfunction, many people with SCI are able to have satisfying sex lives. Physical limitations acquired from SCI affect sexual function and sexuality in broader areas, which in turn has important effects on quality of life. Damage to the spinal cord impairs its ability to transmit messages between the brain and parts of the body below the level of the lesion. This results in lost or reduced sensation and muscle motion, and affects orgasm, erection, ejaculation, and vaginal lubrication. More indirect causes of sexual dysfunction include pain, weakness, and side effects of medications. Psycho-social causes include depression and altered self-image. Many people with SCI have satisfying sex lives, and many experience sexual arousal and orgasm. People with SCI may employ a variety of adaptations to help carry on their sex lives healthily, by focusing on different areas of the body and types of sexual acts. Neural plasticity may account for increases in sensitivity in parts of the body that have not lost sensation, so people often find newly sensitive erotic areas of the skin in erogenous zones or near borders between areas of preserved and lost sensation.

Drugs, devices, surgery, and other interventions exist to help men achieve erection and ejaculation. Although male fertility is reduced, many men with SCI can still father children, particularly with medical interventions. Women's fertility is not usually affected, although precautions must be taken for safe pregnancy and delivery. People with SCI need to take measures during sexual activity to deal with SCI effects such as weakness and movement limitations, and to avoid injuries such as skin damage in areas of reduced sensation. Education and counseling about sexuality is an important part of SCI rehabilitation but is often missing or insufficient. Rehabilitation for children and adolescents aims to promote the healthy development of sexuality and includes education for them and their families. Culturally inherited biases and stereotypes negatively affect people with SCI, particularly when held by professional caregivers. Body image and other insecurities affect sexual function and have profound repercussions on self-esteem and self-concept. SCI causes difficulties in romantic partnerships, due to problems with sexual function and to other stresses introduced by the injury and disability, but many of those with SCI have fulfilling relationships and marriages. Relationships, self-esteem, and reproductive ability are all aspects of sexuality, which encompasses not just sexual practices but a complex array of factors: cultural, social, psychological, and emotional influences.

Sexuality and identity

Sexuality is an important part of each person's identity, although some people might have no interest in sex. Sexuality has biological, psychological, emotional, spiritual, social, and cultural aspects.[1] It involves not only sexual behaviors but relationships, self-image, sex drive,[2] reproduction, sexual orientation, and gender expression.[3] Each person's sexuality is influenced by lifelong socialization, in which factors such as religious and cultural background play a part,[4] and is expressed in self-esteem and the beliefs one holds about oneself (identifying as a woman, or as an attractive person).[1]

SCI is extremely disruptive to sexuality, and it most frequently happens to young people, who are at a peak in their sexual and reproductive lives.[3][5] Yet the importance of sexuality as a part of life is not diminished by a disabling injury.[6] Although for years people with SCI were believed to be asexual, research has shown sexuality to be a high priority for people with SCI[7] and an important aspect of quality of life.[8][9] In fact, of all abilities they would like to have return, most paraplegics rated sexual function as their top priority, and most tetraplegics rated it second, after hand and arm function.[10][11] Sexual function has a profound impact on self-esteem and adjustment to life post-injury.[12] People who are able to adapt to their changed bodies and to have satisfying sex lives have better overall quality of life.[5]

Sexual function

SCI usually causes sexual dysfunction,[13] due to problems with sensation and the body's arousal responses. The ability to experience sexual pleasure and orgasm are among the top priorities for sexual rehabilitation among injured people.[14]

Much research has been done into erection.[14] By two years post-injury, 80% of men recover at least partial erectile function,[15] though many experience problems with the reliability and duration of their erections if they do not use interventions to enhance them.[16] Studies have found that half[15] or up to 65% of men with SCI have orgasms,[17] although the experience may feel different than it did before the injury.[15] Most men say it feels weaker, and takes longer and more stimulation to achieve.[18]

Common problems women experience post-SCI are pain with intercourse and difficulty achieving orgasm.[19] Around half of women with SCI are able to reach orgasm, usually when their genitals are stimulated.[20] Some women report the sensation of orgasm to be the same as before the injury, and others say the sensation is reduced.[5]

Complete and incomplete injury

The severity of the injury is an important aspect in determining how much sexual function returns as a person recovers.[15][21] According to the American Spinal Injury Association grading scale, an incomplete SCI is one in which some amount of sensation or motor function is preserved in the rectum.[10] This indicates that the brain can still send and receive some messages to the lowest parts of the spinal cord, beyond the damaged area. In people with incomplete injury, some or all of the spinal tracts involved in sexual responses remain intact, allowing, for example, orgasms like those of uninjured people.[22] In men, having an incomplete injury improves chances of being able to achieve erections[21][23] and orgasms over those with complete injuries.[24][25]

Even people with complete SCI, in whom the spinal cord cannot transmit any messages past the level of the lesion, can achieve orgasm.[15][17][26] In 1960, in one of the earliest studies to look at orgasm and SCI, the term phantom orgasm was coined to describe women's perception of orgasmic sensations despite SCI—but subsequent studies have suggested the experience is not merely psychological.[10] Men with complete SCI report sexual sensations at the time of ejaculation, accompanied by physical signs normally found at orgasm, such as increased blood pressure.[26] Women can experience orgasm with vibration to the cervix regardless of level or completeness of injury; the sensation is the same as uninjured women experience.[27] The peripheral nerves of the parasympathetic nervous system that carry messages to the brain (afferent nerve fibers) may explain why people with complete SCI feel sexual and climactic sensations.[26] One proposed explanation for orgasm in women despite complete SCI is that the vagus nerve bypasses the spinal cord and carries sensory information from the genitals directly to the brain.[10][25][28][29] Women with complete injuries can achieve sexual arousal and orgasm through stimulation of the clitoris, cervix, or vagina, which are each innervated by different nerve pathways, which suggests that even if SCI interferes with one area, the function might be preserved in others.[30] In both injured and uninjured people, the brain is responsible for the way sensations of climax are perceived: the qualitative experiences associated with climax are modulated by the brain, rather than a specific area of the body.[26]

Level of injury

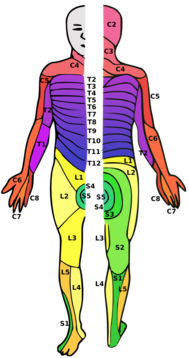

In addition to completeness of injury, the location of the damage on the spinal cord influences how much sexual function is retained or regained after injury.[19][31] Injuries can occur in the cervical (neck), thoracic (back), lumbar (lower back), or sacral (pelvic) levels.[32] Between each pair of vertebrae, spinal nerves branch off of the spinal cord and carry information to and from specific parts of the body.[32] The location of injury to the spinal cord maps to the body, and the area of skin innervated by a specific spinal nerve is called a dermatome. All dermatomes below the level of injury to the spinal cord may lose sensation.[33]

An injury at a lower point on the spine does not necessarily mean better sexual function; for example, people with injuries in the sacral region are less likely to be able to orgasm than those with injuries higher on the spine.[34] Women with injuries above the sacral level have a greater likelihood of orgasm in response to stimulation of the clitoris than those with sacral injuries (59% vs 17%).[35] In men, injuries above the sacral level are associated with better function in terms of erections and ejaculation, and fewer and less severe reports of dysfunction.[17] This may be due to reflexes that do not require input from the brain, which sacral injuries might interrupt.[17]

Psychogenic and reflexogenic responses

The body's physical arousal response (vaginal lubrication and engorgement of the clitoris in women and erection in men) occurs due to two separate pathways which normally work together: psychogenic and reflex.[36] Arousal due to fantasies, visual input, or other mental stimulation is a psychogenic sexual experience, and arousal resulting from physical contact to the genital area is reflexogenic.[37] In psychogenic arousal, messages travel from the brain via the spinal cord to the nerves in the genital area.[38] The psychogenic pathway is served by the spinal cord at levels T11–L2.[39] Thus people injured above the level of the T11 vertebra do not usually experience psychogenic erection or vaginal lubrication, but those with an injury below T12 can.[15] Even without these physical responses, people with SCI often feel aroused, just as uninjured people do.[15] The ability to feel the sensation of a pinprick and light touch in the dermatomes for T11–L2 predicts how well the ability to have psychogenic arousal is preserved in both sexes.[40][16] Input from the psychogenic pathway is sympathetic, and most of the time it sends inhibitory signals that prevent the physical arousal response; in response to sexual stimulation, excitatory signals are increased and inhibition is reduced.[41] Removing the inhibition that is normally present allows the spinal reflexes that trigger the arousal response to take effect.[41]

The reflexogenic pathway activates the parasympathetic nervous system in response to the sensation of touch.[42] It is mediated by a reflex arc that goes to the spinal cord (not to the brain)[42] and is served by the sacral segments of the spinal cord at S2–S4.[39][37] A woman with a spinal cord lesion above T11 may not be able to experience psychogenic vaginal lubrication, but may still have reflex lubrication if her sacral segments are uninjured.[27] Likewise, although a man's ability to get a psychogenic erection when mentally aroused may be impaired after a higher-level SCI, he may still be able to get a reflex or "spontaneous" erection.[21][27] These erections may result in the absence of psychological arousal when the penis is touched or brushed, e.g. by clothing,[43] but they do not last long and are generally lost when the stimulus is removed.[15] Reflex erections may increase in frequency after SCI, due to the loss of inhibitory input from the brain that would suppress the response in an uninjured man.[39] Conversely, an injury below the S1 level impairs reflex erections but not psychogenic erections.[21] People who have some preservation of sensation in the dermatomes at the S4 and S5 levels and display a bulbocavernosus reflex (contraction of the pelvic floor in response to pressure on the clitoris or glans penis) are usually able to experience reflex erections or lubrication.[43] Like other reflexes, reflexive sexual responses may be lost immediately after injury but return over time as the individual recovers from spinal shock.[44]

Factors in reduced function

Most people with SCI have problems with the body's physical sexual arousal response.[7][45] Problems that result directly from impaired neural transmission are called primary sexual dysfunction.[46] The function of the genitals is almost always affected by SCI, by alteration, reduction, or complete loss of sensation.[47] Neuropathic pain, in which damaged nerve pathways signal pain in the absence of any noxious stimulus, is common after SCI[48] and interferes with sex.[49][50]

Secondary dysfunction results from factors that follow from the injury, such as loss of bladder and bowel control or impaired movement.[46] The main barrier to sexual activity that people with SCI cite is physical limitation; e.g. balance problems and muscle weakness cause difficulty with positioning.[19] Spasticity, tightening of muscles due to increased muscle tone, is another complication that interferes with sex.[51] Some medications have side effects that impede sexual pleasure or interfere with sexual function: antidepressants, muscle relaxants, sleeping pills and drugs that treat spasticity.[52] Hormonal changes that alter sexual function may take place after SCI; levels of prolactin heighten, women temporarily stop menstruating (amenorrhea), and men experience reduced levels of testosterone.[15] Testosterone deficiency causes reduced libido, increased weakness, fatigue, and failure to respond to erection-enhancing drugs.[53][54]

Tertiary sexual dysfunction results from psychological and social factors.[46] Reduced libido, desire, or experience of arousal could be due to psychological or situational factors such as depression, anxiety, and changes in relationships.[43] Both sexes experience reduced sexual desire after SCI,[31] and almost half of men and almost three quarters of women have trouble becoming psychologically aroused.[7][11] Depression is the most common cause of problems with arousal in people with SCI.[55] People frequently experience grief and despair initially after the injury.[56] Anxiety, substance use disorders and alcohol use disorder may increase after discharge from a hospital as new challenges occur, which can exacerbate sexual difficulties.[57] Substance use increase unhealthy behaviors, straining relationships and social functioning.[58] SCI can lead to significant insecurities, which have repercussions for sexuality and self-image. SCI often affects body image, either due to the host of changes in the body that affect appearance (e.g. unused muscles in the legs become atrophied), or due to changes in self-perception not directly from physical changes.[59] People frequently find themselves less attractive and expect others not to be attracted to them after SCI.[5] These insecurities cause fear of rejection and deter people from initiating contact or sexual activity[5] or engaging in sex.[59] Feelings of undesirability or worthlessness even lead some to suggest to their partners that they find someone non-disabled.[60]

Fertility

Male

Men with SCI rank the ability to father children among their highest concerns relating to sexuality.[61] Male fertility is reduced after SCI, due to a combination of problems with erections, ejaculation, and quality of the semen.[21][62] As with other types of sexual response, ejaculation can be psychogenic or reflexogenic, and the level of injury affects a man's ability to experience each type.[17] As many as 95% of men with SCI have problems with ejaculation (anejaculation),[15] possibly due to impaired coordination of input from different parts of the nervous system.[19] Erection, orgasm, and ejaculation can each occur independently,[10] although the ability to ejaculate seems linked to the quality of the erection,[24] and the ability to orgasm is linked to the ejaculation facility.[16] Even men with complete injuries may be able to ejaculate, because other nerves involved in ejaculation can effect the response without input from the spinal cord.[8] In general, the higher the level of injury, the more physical stimulation the man needs to ejaculate.[24] Conversely, premature or spontaneous ejaculation can be a problem for men with injuries at levels T12–L1.[24] It can be severe enough that ejaculation is provoked by thinking a sexual thought, or for no reason at all, and is not accompanied by orgasm.[63]

Most men have a normal sperm count, but a high proportion of sperm are abnormal; they are less motile and do not survive as well.[31][62] The reason for these abnormalities is not known, but research points to dysfunction of the seminal vesicles and prostate, which concentrate substances that are toxic to sperm.[64][65] Cytokines, immune proteins which promote an inflammatory response, are present at higher concentrations in semen of men with SCI,[65][66] as is platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase; both are harmful to sperm.[65][66] Another immune-related response to SCI is the presence of a higher number of white blood cells in the semen.[62]

Female

The numbers of women with SCI giving birth and having healthy babies are increasing.[67] Around a half to two-thirds of women with SCI report they might want to have children,[25] and 14–20% do get pregnant at least once.[64] Although female fertility is not usually permanently reduced by SCI, there is a stress response that can happen immediately post-injury that alters levels of fertility-related hormones in the body.[68] In about half of women, menstruation stops after the injury but then returns within an average of five months—it returns within a year for a large majority.[69] After menstruation returns, women with SCI become pregnant at a rate close to that of the rest of the population.[21]

Pregnancy is associated with greater-than-normal risks in women with SCI,[70] among them increased risk of deep vein thrombosis,[71] respiratory infection, and urinary tract infection.[72] Considerations exist such as maintaining proper positioning in a wheelchair,[43] prevention of pressure sores, and increased difficulty moving due to weight gain and changes in center of balance.[73] Assistive devices may need to be altered and medications changed.[74] For women with injuries above T6, a risk during labor and delivery that threatens both mother and fetus is autonomic dysreflexia, in which the blood pressure increases to dangerous levels high enough to cause potentially deadly stroke.[73] Drugs such as nifedipine and captopril can be used to manage an episode if it occurs, and epidural anesthesia helps although it is not very reliable in women with SCI.[75] Anesthesia is used for labor and delivery even for women without sensation, who may only experience contractions as abdominal discomfort, increased spasticity, and episodes of autonomic dysreflexia.[67] Reduced sensation in the pelvic area means women with SCI usually have less painful delivery; in fact, they may fail to realize when they go into labor.[76] If there are deformities in the pelvis or spine caesarian section may be necessary.[77] Babies of women with SCI are more likely to be born prematurely, and, premature or not, they are more likely to be small for their gestational time.[77]

Management

Erectile problems

Although erections are not necessary for satisfying sexual encounters, many men see them as important, and treating erectile dysfunction improves their relationships and quality of life.[78] Whatever treatment is used, it works best in combination with talk-oriented therapy to help integrate it into the sex life.[65] Oral medications and mechanical devices are the first choice in treatment because they are less invasive,[79] are often effective, and are well tolerated.[80] Oral medications include sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), and vardenafil (Levitra).[81][65] Penis pumps induce erections without the need for drugs or invasive treatments. To use a pump, the man inserts his penis into a cylinder, then pumps it to create a vacuum which draws blood into the penis, making it erect.[82][65] He then slides a ring from the outside of the cylinder onto the base of the penis to hold the blood in and maintain the erection.[82][53] A man who is able to get an erection but has trouble maintaining it for long enough can use a ring by itself.[63][83] The ring cannot be left on for more than 30 minutes and cannot be used at the same time as anticoagulant medications.[53]

If oral medications and mechanical treatments fail, the second choice is local injections:[79] medications such as papaverine and prostaglandin that alter the blood flow and trigger erection are injected into the penis.[84] This method is preferred for its effectiveness, but can cause pain and scarring.[85] Another option is to insert a small pellet of medication into the urethra, but this requires higher doses than injections and may not be as effective.[85] Topical medications to dilate the blood vessels have been used, but are not very effective or well tolerated.[80] Electrical stimulation of efferent nerves at the S2 level can be used to trigger an erection that lasts as long as the stimulation does.[86] Surgical implants, either of flexible rods or inflatable tubes, are reserved for when other methods fail because of the potential for serious complications, which occur in as many as 10% of cases.[80] They carry the risk of eroding penile tissue (breaking through the skin).[87] Although satisfaction among men who use them is high, if they do need to be removed implants make other methods such as injections and vacuum devices unusable due to tissue damage.[80] It is also possible for erectile dysfunction to exist not as a direct result of SCI but due to factors such as major depression, diabetes, or drugs such as those taken for spasticity.[88] Finding and treating the root cause may alleviate the problem. For example, men who experience erectile problems as the result of a testosterone deficiency can receive androgen replacement therapy.[43]

Ejaculation and male fertility

Without medical intervention, the male fertility rate after SCI is 5–14%, but the rate increases with treatments.[89] Even with all available medical interventions, fewer than half of men with SCI can father children.[90] Assisted insemination is usually required.[91] As with erection, therapies used to treat infertility in uninjured men are used for those with SCI.[65] For anejaculation in SCI, the first-line method for sperm retrieval is penile vibratory stimulation (PVS).[8][81][92][93] A high-speed vibrator is applied to the glans penis to trigger a reflex that causes ejaculation, usually within a few minutes.[92] Reports of efficacy with PVS range from 15 to 88%, possibly due to differences in vibrator settings and experience of clinicians, as well as level and completeness of injury.[92] Complete lesions strictly above Onuf's nucleus (S2–S4) are responsive to PVS in 98%, but complete lesions of the S2–S4 segments are not.[8] In case of failure with PVS, spermatozoa are sometimes collected by electroejaculation:[8][92][93] an electrical probe is inserted into the rectum, where it triggers ejaculation.[81] The success rate is 80–100%, but the technique requires anaesthesia and does not have the potential to be done at home that PVS has.[21] Both PVS and electroejaculation carry a risk of autonomic dysreflexia, so drugs to prevent the condition can be given in advance and blood pressure is monitored throughout the procedures for those who are susceptible.[94] Massage of the prostate gland and seminal vesicles is another method to retrieve stored sperm.[65][92] If these methods fail to cause ejaculation or do not yield sufficient usable sperm, sperm can be surgically removed by testicular sperm extraction[21] or percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration.[8] These procedures yield sperm in 86–100% of cases, but nonsurgical treatments are preferred.[21] Premature or spontaneous ejaculation is treated with antidepressants including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are known to delay ejaculation as a side effect.[63]

Women

Compared with the options available for treating sexual dysfunction in men (for whom results are concretely observable), those available for women are limited.[95] For example, PDE5 inhibitors, oral medications for treating erectile dysfunction in men, have been tested for their ability to increase sexual responses such as arousal and orgasm in women—but no controlled trials have been done in women with SCI, and trials in other women yielded only inconclusive results.[96] In theory, women's sexual response could be improved using a vacuum device made to draw blood into the clitoris, but few studies on treatments for sexual function in women with SCI have been carried out.[83] There is a particular paucity of information outside the area of reproduction.[5]

Education and counseling

Counseling about sex and sexuality by medical professionals, psychologists, social workers, and nurses is a part of most SCI rehabilitation programs.[70] Education is part of the follow-up treatment for people with SCI,[20] as are psychotherapy, peer mentorship, and social activities; these are helpful for improving skills needed for socializing and relationships.[15] Rather than addressing sexual dysfunction strictly as a physical problem, appropriate sexual rehabilitation care takes into account the individual as a whole, for example addressing issues with relationships and self-esteem.[97] Sexual counseling includes teaching techniques to manage depression and stress, and to increase attention to preserved sensations during sexual activity.[55] Education includes information about birth control or assistive devices such as those for positioning in sex, or advice and ideas for addressing problems such as incontinence and autonomic dysreflexia.[98]

Many SCI patients have received misinformation about the effects of their injury on their sexual function and benefit from education about it.[10] Although sexual education shortly after injury is known to be helpful and desired, it is frequently missing in rehabilitation settings;[15] a common complaint from those who go through rehabilitation programs is that they offer insufficient information about sexuality.[57] Longer-term education and counseling on sex after discharge from a hospital setting are especially important,[99] yet sexuality is one of the most often neglected areas in long-term SCI rehabilitation, particularly for women.[61] Care providers may refrain from addressing the topic because they feel intimidated or unequipped to handle it.[11] Clinicians must be circumspect in bringing up sexual matters since people may be uncomfortable with or unready for the subject.[43] Many patients wait for providers to broach the topic even if they do want the information.[57]

A person's experience in managing sexuality after the injury relies not only on physical factors like severity and level of the injury, but on aspects of life circumstances and personality such as sexual experience and attitudes about sex.[15] As well as evaluating physical concerns, clinicians must take into account factors that affect each patient's situation: gender, age, cultural, and social factors.[71] Aspects of patients' cultural and religious backgrounds, even if unnoticed before the injury caused sexual dysfunction, affect care and treatments—particularly when cultural attitudes and assumptions of patients and care providers conflict.[100] Health professionals must be sensitive to issues of sexual orientation and gender identity, showing respect and acceptance while communicating, listening, and emotionally supporting.[43] Providers who treat SCI have been found to assume their patients are heterosexual or to exclude LGBTQ patients from their awareness, potentially resulting in substandard care.[101] Academic research on sexuality and disability under-represents LGBTQ perspectives as well.[3]

As well as the patient, the partner of an injured person frequently needs support and counseling.[102] It can help with adjustment to a new relationship dynamic and self-image (such as being placed in the role of a caretaker) or with stresses that arise in the sexual relationship.[102] Frequently, partners of injured people must contend with feelings like guilt, anger, anxiety, and exhaustion while dealing with the added financial burden of lost wages and medical expenses.[103] Counseling aims to strengthen the relationship by improving communication and trust.[29]

Children and adolescents

Not only does SCI present children and adolescents with many of the same difficulties adults face, it affects the development of their sexuality.[104] Although substantial research exists on SCI and sexuality in adults, very little exists on the ways in which it affects development of sexuality in young people.[105] Injured children and adolescents need ongoing, age-appropriate sex education that addresses questions of SCI as it relates to sexuality and sexual function.[106] Very young children become aware of their disabilities before their sexuality, but as they age they become curious just as non-disabled children do, and it is appropriate to provide them with increasing amounts of information.[105] Caregivers help the child and family prepare for transition into adulthood, including in sexuality and social interaction, beginning early and intensifying during adolescence.[107] Parents need education about the effects of SCI on sexual function so that they can answer their children's questions.[105] Once patients reach their teens, they need more specific information about pregnancy, birth control, self-esteem, and dating.[77] Teenagers with lost or reduced genital sensation benefit from education about alternative ways to experience pleasure and satisfaction from sexual acts.[108] The teen years are often particularly difficult for those with SCI, in terms of body image and relationships.[109] Given the importance they place on sexuality and privacy, adolescents may experience humiliation when parents or caregivers bathe them or take care of bowel and bladder needs.[110] They can benefit from sexuality counseling, support groups,[109] and mentoring by adults with SCI who can share experiences and lead discussions with peers.[77] With the right care and education from family and professionals, injured children and adolescents can develop into sexually healthy adults.[19]

Changes in sexual practices

People make a variety of sexual adaptations to help adjust to SCI. They often change their sexual practices, moving away from genital stimulation and intercourse[5] and toward greater emphasis on touching above the level of injury and other aspects of intimacy such as kissing and caressing.[20] It is necessary to discover new sexual positions if ones used previously have become too difficult.[19] Other factors that enhance sexual pleasure are positive memories, fantasies, relaxation, meditation, breathing techniques, and most importantly, trust with a partner.[83] People with SCI can make use of visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile stimuli.[111] It is possible to train oneself to be more mindful of the cerebral aspects of sex and of feeling in areas of the body that have sensation; this increases chances of orgasm.[83] The importance of desire and comfort is the reasoning behind the quip "the most important sexual organ is the brain."[112]

Adjusting to post-injury changes in the body's sensation is difficult enough to cause some to give up on the idea of satisfying sex at first.[113] But changes in sensitivity above and at the level of injury occur over time; people may find erogenous zones like the nipples or ears have become more sensitive, enough to be sexually satisfying.[15] They may discover new erogenous zones that were not erotic before the injury; care providers can help direct this discovery.[18] These erogenous areas can even lead to orgasm when stimulated.[43][46] Such changes may result from "remapping" of sensory areas in the brain due to neuroplasticity, particularly when sensation in the genitals is completely lost.[24] Commonly there is an area on the body between the areas where sensation is lost and those where is preserved called a "transition zone" that has increased sensitivity and is often sexually pleasurable when stimulated.[43] Also known as a "border zone", this area may feel the way the penis or clitoris did before injury, and can even give orgasmic sensation.[114] Due to such changes in sensation, people are encouraged to explore their bodies to discover what areas are pleasurable.[115] Masturbation is a useful way to learn about the body's new responses.[116]

Tests exist to measure how much sensation a person has retained in the genitals after an injury, which are used to tailor treatment or rehabilitation.[20] Sensory testing helps people learn to recognize the sensations associated with arousal and orgasm.[117] Injured people who are able to achieve orgasms from stimulation to the genitals may need stimulation for a longer time or at a greater intensity.[10] Sex toys such as vibrators are available, e.g. to enhance sensation in areas of reduced sensitivity, and these can be modified to accommodate disabilities.[43] For example, a hand strap can be added to a vibrator or dildo to assist someone with poor hand function.[44]

Considerations for sexual activity

SCI presents extra needs to consider for sexual activity; for example muscle weakness and movement limitations restrict options for positioning.[2] Pillows or devices such as wedges can be placed to help achieve and maintain a desired position for people affected by weakness or movement limitations.[44] Assistive devices exist to aid in motion, such as sliding chairs to provide pelvic thrust.[15] Spasticity and pain also create barriers to sexual activity;[115] these changes may require couples to use new positions, such as seated in a wheelchair.[114] A warm bath can be taken prior to sex,[118] and massage and stretching can be incorporated into foreplay to ease spasticity.[44]

Another consideration is loss of sensation, which puts people at risk for wounds such as pressure sores and injuries that could become worse before being noticed.[43][119] Friction from sexual activity may damage the skin, so it is necessary after sex to inspect areas that could have been hurt, particularly the buttocks and genital area.[43][119] People who already have pressure sores must take care not to make the wounds worse.[43] Irritation to the genitals increases risk for vaginal infections, which get worse if they go unnoticed.[13] Women who do not get sufficient vaginal lubrication on their own can use a commercially available personal lubricant to decrease friction.[44]

Another risk is autonomic dysreflexia (AD), a medical emergency involving dangerously high blood pressure.[120] People at risk for AD can take medications to help prevent it before sex, but if it does occur they must stop and seek treatment.[119] Mild signs of AD such as slightly high blood pressure frequently do accompany sexual arousal and are not cause for alarm.[44] In fact, some interpret the symptoms of AD that occur during sexual activity as pleasant or arousing,[121] or even climactic.[44]

A concern for sexual activity that is not dangerous but that can be upsetting for both partners is bladder or bowel leakage due to urinary or fecal incontinence.[122] Couples can prepare for sex by draining the bladder using intermittent catheterization[5] or placing towels down in advance.[123] People with indwelling urinary catheters must take special care with them, removing them or taping them out of the way.[19][124]

Birth control is another consideration: women with SCI are usually not prescribed oral contraceptives since the hormones in them increase the risk of blood clots,[47][125] for which people with SCI are already at elevated risk. Intrauterine devices could have dangerous complications that could go undetected if sensation is reduced.[47][73] Diaphragms that require something to be inserted into the vagina are not usable by people with poor hand function.[126] An option of choice for women is for partners to use condoms.[126][125]

Long-term adjustment

In the first months after an injury, people commonly prioritize other aspects of rehabilitation over sexual matters, but in the long term, adjustment to life with SCI necessitates addressing sexuality.[43] Although physical, psychological and emotional factors militate to reduce the frequency of sex after injury, it increases after time.[15] As years go by, the odds that a person will become involved in a sexual relationship increase.[121] Difficulties adjusting to a changed appearance and physical limitations contribute to reduced frequency of sexual acts, and improved body image is associated with an increase.[5] Like frequency, sexual desire and sexual satisfaction often decrease after SCI.[105] The reduction in women's sexual desire and frequency may be in part because they believe they can no longer enjoy sex, or because their independence or social opportunities are reduced.[5] As time goes by people usually adjust sexually, adapting to their changed bodies.[19] Some 80% of women return to being sexually active,[50] and the numbers who report being sexually satisfied range from 40 to 88%.[127] Although women's satisfaction is usually lower than before the injury,[5] it improves as time passes.[29] Women report higher rates of sexual satisfaction than men post-SCI for as many as 10–45 years.[57] More than a quarter of men have substantial problems with adjustment to their post-injury sexual functioning.[128] Sexual satisfaction depends on a host of factors, some more important than the physical function of the genitals: intimacy, quality of relationships, satisfaction of partners,[15] willingness to be sexually experimental, and good communication.[19] Genital function is not as important to men's sexual satisfaction as are their partners' satisfaction and intimacy in their relationships.[70] For women, quality of relationships, closeness with partners, sexual desire, and positive body image, as well as the physical function of the genitals, contribute sexual satisfaction.[129] For both sexes, long-term relationships are associated with higher sexual satisfaction.[15]

Relationships

A catastrophic injury such as SCI puts strain on marriages and other romantic relationships, which in turn has important implications for quality of life. Partners of injured people often feel out of control, overwhelmed, angry, and guilty while having added work related to the injury, less help with responsibilities like parenting, and loss of wages.[130] Relationship stress and excessive dependence in relationships increases risk of depression for the person with SCI; supportive relationships are protective.[131] Relationships change as partners take on new roles, such as that of caregiver,[57] which may conflict with the role of partner and require substantial sacrifice of time and self-care.[103] These changes in responsibilities may mean a reverse in societally determined gender roles within relationships; inability to fulfil these roles affects sexuality in general.[59] Sexual dysfunction is a stressor in relationships. People are often as concerned about failing to keep a partner satisfied as they are about meeting their own sexual needs.[15] In fact, two of the top reasons people with SCI cite for wanting to have sex are for intimacy and to keep a partner.[71] The frequency of sex correlates with the desire of the uninjured partner.[118]

Although problems with sexual function that result from SCI play a part in some divorces, they are not as important as emotional maturity in determining the success of a marriage.[132] People with SCI get divorced more often than the rest of the population,[103] and marriages that took place before the injury fail more often than those that took place after (33% vs. 21%).[133] People married before the injury report less happy marriages and worse sexual adjustment than those married after, possibly indicating that spouses had difficulty adjusting to the new circumstances.[134] For those who chose to become involved with someone after an injury, the disability was an accepted part of the relationship from the outset.[135] Understanding and acceptance of the limitations that result from the injury on the part of the uninjured partner is an important factor in a successful marriage.[136] Many divorces have been found to be initiated by the injured partner, sometimes due to the depression and denial that often occurs early after the injury.[137] Thus counseling is important, not just for managing changes in self-perception but in perceptions about relationships.[137]

Despite the stresses that SCI places on people and relationships, studies have shown that people with SCI are able to have happy and fulfilling romantic relationships and marriages, and to raise well-adjusted children.[138] People with SCI who wish to be parents may question their ability to raise children and opt not to have them, but studies have shown no difference in parenting outcomes between injured and uninjured groups.[139] Children of women with SCI do not have worse self-esteem, adjustment, or attitudes toward their parents.[77] Women who have children post-SCI have a higher quality of life, even though parenting adds demands and challenges to their lives.[140]

For those who are single when injured or who become single, SCI causes difficulties and insecurities with respect to one's ability to meet new partners[141] and start relationships.[142] In some settings, beauty standards cause people to view disabled bodies as less attractive, limiting the options for sexual and romantic partners of people with disabilities like SCI.[143] Furthermore, physical disabilities are stigmatized, causing people to avoid contact with disabled people, particularly those with highly visible conditions like SCI.[144] The stigma may cause people with SCI to experience self-consciousness and embarrassment in public.[144] They can increase their social success by using impression management techniques to change how they are perceived and create a more positive image of themselves in others' eyes.[145] Physical limitations create difficulties; with lowered independence comes reduced social interaction and fewer opportunities to find partners.[5] Difficulties with mobility and the lack of disabled accessibility of social spaces (e.g. lack of wheelchair ramps) create a further barrier to social activity and limit the ability to meet partners. Isolation and its associated risk of depression can be limited by participating in physical activities, social gatherings, clubs, and online chat and dating.[57]

Society and culture

Negative societal attitudes and stereotypes about people with disabilities like SCI affect interpersonal interactions and self-image, with important implications for quality of life. In fact, for women, psychological factors have a more important impact on sexual adjustment and activity than physical ones.[29] Negative attitudes about disability (along with relationships and social support) are more predictive of outcome than even the level or completeness of injury.[146] Stereotypes exist that people with SCI (particularly women) are uninterested in, unsuitable for, or incapable of sexual relationships or encounters.[147] "People think we can only date people in wheelchairs, that we're lucky to get any guy, that we can't be picky", remarked Mia Schaikewitz, who is profiled in Push Girls, a 2012 reality series about four women with SCI.[148] Not only do they affect injured people's self-image, these stereotypes are particularly harmful when held by counselors and professionals involved in rehabilitation.[147] Caregivers affected by these culturally transmitted beliefs may treat their patients as asexual, particularly if the injury occurred at a young age and the patient never had sexual experiences.[4] Failure to recognize injured people's sexual and reproductive capacity restricts their access to birth control, information about sexuality, and sexual health-related medical care such as annual gynecological exams.[3] Another common belief that affects sexual rehabilitation is that sex is strictly about genital function; this could cause caregivers to discount the importance of the rest of the body and of the individual.[34]

Cultural attitudes toward gender roles have profound effects on people with SCI.[149] The injury can cause insecurities surrounding sexual identity, particularly if the disability precludes fulfilment of societally taught gender norms.[150] Female beauty standards propagated by mass media and culture portray the ideal woman as non-disabled: as one fashion model with a SCI commented, "when you have a devastating injury or disability, you're not often thought of as sensual or pretty because you don't look like the women in the magazines."[151] Inability to meet these standards can lower self-esteem, even if these ideals are also unattainable for most non-disabled women.[152] Poorer self-esteem is associated with worse sexual adjustment and quality of life, and higher rates of loneliness, stress, and depression.[153] Males are also affected by societal expectations, such as notions about masculinity and sexual prowess.[128][154] Men from some traditional backgrounds may feel performance pressure that emphasizes the ability to have erections and sexual intercourse.[149] Men who have a strong sexual desire but who are not able to perform sexually may be at increased risk for depression, particularly when they believe strongly in traditional masculine gender norms with sexual function as core to the male identity.[128][154] Men who strongly believe in these traditional roles may feel sexually inadequate, unmanly, insecure, and less satisfied with life.[128] Since sexual dysfunction has this negative impact on self-esteem, treatment of erectile dysfunction can have a psychological benefit even though it does not help with physical sensation.[149] SCI may necessitate reappraisal and rejection of assumptions about gender norms and sexual function in order to adjust healthily to the disability: those who are able to change the way they think about gender roles may have better life satisfaction and outcomes with rehabilitation.[128] Counseling is helpful in this reassessment process.[128]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Whipple 2013, p. 19.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Fritz, H.A.; Dillaway, H.; Lysack C.L. (2015). "'Don't think paralysis takes away your womanhood': Sexual intimacy after spinal cord injury". American Journal of Occupational Therapy 69 (2): 1–10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2015.015040. PMID 26122683.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Francoeur 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 Cramp J.D.; Courtois F.J.; Ditor D.S. (2015). "Sexuality for women with spinal cord injury". Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 41 (3): 238–53. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2013.869777. PMID 24325679.

- ↑ Hardoff, D (2012). "Sexuality in young people with physical disabilities: Theory and practice". Georgian Medical News (210): 23–26. PMID 23045416.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Elliott 2009, p. 514.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Chehensse, C.; Bahrami, S.; Denys, P.; Clément, P.; Bernabé, J.; Giuliano, F. (2013). "The spinal control of ejaculation revisited: A systematic review and meta-analysis of anejaculation in spinal cord injured patients". Human Reproduction Update 19 (5): 507–26. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt029. PMID 23820516.

- ↑ Simpson, L.A.; Eng, J.J.; Hsieh, J.T.C.; Wolfe, D.L. (2012). "The Health and Life Priorities of Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review". Journal of Neurotrauma 29 (8): 1548–55. doi:10.1089/neu.2011.2226. PMID 22320160.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Alexander, M.; Rosen, R.C. (2008). "Spinal cord injuries and orgasm: A review". Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 34 (4): 308–24. doi:10.1080/00926230802096341. PMID 18576233.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 Elliott 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 225.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Borisoff, J.F.; Elliott, S.L.; Hocaloski, S; Birch, G.E. (2010). "The development of a sensory substitution system for the sexual rehabilitation of men with chronic spinal cord injury". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7 (11): 3647–58. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01997.x. ISSN 1743-6095. PMID 20807328.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 15.16 15.17 15.18 Hess, M.J.; Hough, S. (2012). "Impact of spinal cord injury on sexuality: Broad-based clinical practice intervention and practical application". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 35 (4): 211–18. doi:10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000025. PMID 22925747.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 Elliott 2012, p. 146.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 228.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1507.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 19.8 Ricciardi, R.; Szabo, C.M.; Poullos, A.Y. (2007). "Sexuality and spinal cord injury". Nursing Clinics of North America 42 (4): 675–84. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2007.08.005. PMID 17996763.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Perrouin-Verbe, B.; Courtois, F.; Charvier, K.; Giuliano, F. (2013). "Sexuality of women with neurologic disorders". Progrès en Urologie 23 (9): 594–600. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2013.01.004. PMID 23830253.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 Dimitriadis, F.; Karakitsios, K.; Tsounapi, P.; Tsambalas, S.; Loutradis, D.; Kanakas, N.; Watanabe, N.T.; Saito, M. et al. (2010). "Erectile function and male reproduction in men with spinal cord injury: A review". Andrologia 42 (3): 139–65. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00969.x. PMID 20500744.

- ↑ Elliott 2010a, p. 415.

- ↑ Sabharwal 2013, p. 306.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Elliott 2009, p. 518.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 25.2 Daroff et al. 2012, p. 980.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Courtois, F.; Charvier, K.; Vézina, J.G.; Journel, N.M.; Carrier, S.; Jacquemin, G.; Côté I. (2011). "Assessing and conceptualizing orgasm after a spinal cord injury". BJU International 108 (10): 1624–33. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10168.x. PMID 21507183.

- ↑ Jump up to: 27.0 27.1 27.2 Rees, P.M.; Fowler, C.J.; Maas, C.P. (2007). "Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders". Lancet 369 (9560): 512–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60238-4. PMID 17292771.

- ↑ Komisaruk, B.R.; Whipple, B.; Crawford, A.; Liu, W.C.; Kalnin, A.; Mosier, K. (2004). "Brain activation during vaginocervical self-stimulation and orgasm in women with complete spinal cord injury: fMRI evidence of mediation by the vagus nerves". Brain Research 1024 (1–2): 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.029. PMID 15451368.

- ↑ Jump up to: 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Lombardi, G.; Del Popolo, G.; Macchiarella, A.; Mencarini, M.; Celso, M. (2010). "Sexual rehabilitation in women with spinal cord injury: A critical review of the literature". Spinal Cord 48 (12): 842–49. doi:10.1038/sc.2010.36. PMID 20386552.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, pp. 232–34.

- ↑ Jump up to: 31.0 31.1 31.2 Committee on Spinal Cord Injury; Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health; Institute of Medicine (27 July 2005). Spinal Cord Injury: Progress, Promise, and Priorities. National Academies Press. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-0-309-16520-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ewEJU8Sg-n8C&pg=PA57.

- ↑ Jump up to: 32.0 32.1 Field-Fote 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Spinal Cord Injury: Hope Through Research. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. 2013. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/sci/detail_sci.htm. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ Jump up to: 34.0 34.1 Elliott 2012, p. 155.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 234.

- ↑ Sabharwal 2013, p. 304.

- ↑ Jump up to: 37.0 37.1 The Mayo Clinic 2011, pp. 143–44.

- ↑ The Mayo Clinic 2011, p. 143.

- ↑ Jump up to: 39.0 39.1 39.2 Elliott 2009, p. 516.

- ↑ Elliott 2010a, pp. 413, 431.

- ↑ Jump up to: 41.0 41.1 Elliott 2012, p. 144–45.

- ↑ Jump up to: 42.0 42.1 Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1506.

- ↑ Jump up to: 43.00 43.01 43.02 43.03 43.04 43.05 43.06 43.07 43.08 43.09 43.10 43.11 43.12 43.13 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (2010). "Sexuality and reproductive health in adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 33 (3): 281–336. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689709. PMID 20737805.

- ↑ Jump up to: 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 44.6 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 236.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 144.

- ↑ Jump up to: 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Lombardi, G.; Musco, S.; Kessler, T.M.; Li Marzi, V.; Lanciotti, M.; Del Popolo, G. (2015). "Management of sexual dysfunction due to central nervous system disorders: A systematic review". BJU International 115 (Suppl 6): 47–56. doi:10.1111/bju.13055. PMID 25599613. https://flore.unifi.it/bitstream/2158/1084055/1/manag%20sex%20dysf.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 47.0 47.1 47.2 Miller & Marini 2012, p. 138.

- ↑ Kennedy 2007, p. 96.

- ↑ Alexander, M.S.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Elliott, S.; Kreuter, M.; Sønksen, J. (2011). "International spinal cord injury female sexual and reproductive function basic data set". Spinal Cord 49 (7): 787–90. doi:10.1038/sc.2011.7. PMID 21383760.

- ↑ Jump up to: 50.0 50.1 Wegener, Adams & Rohe 2012, p. 303.

- ↑ The Mayo Clinic 2011, p. 159.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, pp. 225, 236.

- ↑ Jump up to: 53.0 53.1 53.2 Sabharwal 2013, p. 310.

- ↑ Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1519.

- ↑ Jump up to: 55.0 55.1 Florante & Leyson 2013, p. 365.

- ↑ Nicotra, A.; Critchley, H.D.; Mathias, C.J.; Dolan, R.J. (2006). "Emotional and autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury explored using functional brain imaging". Brain 129 (Pt 3): 718–28. doi:10.1093/brain/awh699. PMID 16330503.

- ↑ Jump up to: 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 57.5 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 237.

- ↑ Sabharwal 2013, pp. 396–97.

- ↑ Jump up to: 59.0 59.1 59.2 Miller & Marini 2012, pp. 146–47.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 344.

- ↑ Jump up to: 61.0 61.1 Abramson, C.E.; McBride, K.E.; Konnyu, K.J.; Elliott, S.L.; SCIRE Research Team (2008). "Sexual health outcome measures for individuals with a spinal cord injury: A systematic review". Spinal Cord 46 (5): 320–24. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3102136. PMID 17938640.

- ↑ Jump up to: 62.0 62.1 62.2 Ibrahim, E.; Lynne, C.M.; Brackett, N.L. (2015). "Male fertility following spinal cord injury: An update". Andrology 4 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1111/andr.12119. PMID 26536656.

- ↑ Jump up to: 63.0 63.1 63.2 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 231.

- ↑ Jump up to: 64.0 64.1 Elliott 2012, p. 148.

- ↑ Jump up to: 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 65.6 65.7 Brackett, N.L. (2012). "Infertility in men with spinal cord injury: research and treatment". Scientifica 2012: 578257. doi:10.6064/2012/578257. PMID 24278717.

- ↑ Jump up to: 66.0 66.1 Elliott 2010a, p. 420.

- ↑ Jump up to: 67.0 67.1 Krassioukov, A.; Warburton, D.E.; Teasell, R.; Eng, J.J. (2009). "A systematic review of the management of autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 90 (4): 682–95. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.017. PMID 19345787. PMC 3108991. http://www.archives-pmr.org/article/S0003-9993%2809%2900058-6/abstract.

- ↑ Daroff et al. 2012, p. 981.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 186.

- ↑ Jump up to: 70.0 70.1 70.2 Harvey 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Jump up to: 71.0 71.1 71.2 Bickenbach et al. 2013, p. 75.

- ↑ McKay-Moffat 2007, p. 176.

- ↑ Jump up to: 73.0 73.1 73.2 Elliott 2012, p. 149.

- ↑ Bertschy, S.; Geyh, S.; Pannek, J.; Meyer, T. (2015). "Perceived needs and experiences with healthcare services of women with spinal cord injury during pregnancy and childbirth: A qualitative content analysis of focus groups and individual interviews". BMC Health Services Research 15: 234. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0878-0. PMID 26077955.

- ↑ El-Refai, N.A. (2013). "Anesthetic management for parturients with neurological disorders". Anesthesia: Essays and Researches 7 (2): 147–54. doi:10.4103/0259-1162.118940. PMID 25885824.

- ↑ Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1520–21.

- ↑ Jump up to: 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 77.4 Kim, H.; Murphy, N.; Kim, C.T.; Moberg-Wolff, E.; Trovato, M. (2010). "Pediatric rehabilitation: 5. Transitioning teens with disabilities into adulthood". PM&R 2 (3): S31–37. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.01.001. PMID 20359678.

- ↑ Elliott 2009, p. 521.

- ↑ Jump up to: 79.0 79.1 Elliott 2010a, p. 416.

- ↑ Jump up to: 80.0 80.1 80.2 80.3 Deforge, D.; Blackmer, J.; Moher, D.; Garritty, C.; Cronin, V.; Yazdi, F.; Barrowman, N.; Mamaladze, V. et al. (2004). "Sexuality and reproductive health following spinal cord injury". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary) (109): 1–8. doi:10.1037/e439522005-001. PMID 15643907.

- ↑ Jump up to: 81.0 81.1 81.2 Miller & Marini 2012, p. 140.

- ↑ Jump up to: 82.0 82.1 Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 230.

- ↑ Jump up to: 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 Elliott 2012, p. 150.

- ↑ The Mayo Clinic 2011, p. 145.

- ↑ Jump up to: 85.0 85.1 Elliott 2010a, p. 418.

- ↑ Creasey & Craggs 2012, p. 250.

- ↑ Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 131.

- ↑ Elliott 2010a, p. 413.

- ↑ Ditunno et al. 2012, p. 190.

- ↑ Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1520.

- ↑ Elliott 2010a, p. 410.

- ↑ Jump up to: 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 92.4 Elliott 2012, p. 147.

- ↑ Jump up to: 93.0 93.1 Soler, J.M.; Previnaire, J.G. (2011). "Ejaculatory dysfunction in spinal cord injury men is suggestive of dyssynergic ejaculation". European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 47 (4): 677–81. PMID 22222964. http://www.minervamedica.it/en/getfreepdf/CLppZq29bMhllCAJIv%252B%252FPIF6wgQ0Shvcz45NnmaTRZJZvAGQa%252FumGXsZk%252FKbvciySJ99sa16I8rZ%252FUKNeo3aZg%253D%253D/R33Y2011N04A0677.pdf.

- ↑ Wein et al. 2011, p. 643.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, pp. 234–35.

- ↑ Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1516.

- ↑ Sabharwal 2013, p. 308.

- ↑ Bickenbach et al. 2013.

- ↑ Harvey 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Francoeur 2013, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ "Health care providers' knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy for working with patients with spinal cord injury who have diverse sexual orientations". Physical Therapy 88 (2): 191–98. 2008. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060188. PMID 18029393.

- ↑ Jump up to: 102.0 102.1 Neumann 2013, p. 356.

- ↑ Jump up to: 103.0 103.1 103.2 Sabharwal 2013, p. 406.

- ↑ Flett, P.J. (1992). "The rehabilitation of children with spinal cord injury". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 28 (2): 141–46. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02629.x. PMID 1562363.

- ↑ Jump up to: 105.0 105.1 105.2 105.3 Alexander, M.S.; Alexander, C.J. (2007). "Recommendations for discussing sexuality after spinal cord injury/dysfunction in children, adolescents, and adults". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 30 (Suppl 1): S65–70. doi:10.1080/10790268.2007.11753971. PMID 17874689.

- ↑ Vogel, Betz & Mulcahey 2012, p. 140.

- ↑ Vogel, Betz & Mulcahey 2012, p. 131.

- ↑ "Sexuality of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities". Pediatrics 118 (1): 398–403. 2006. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1115. PMID 16818589. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/1/398.

- ↑ Jump up to: 109.0 109.1 Sabharwal 2013, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Vogel, Betz & Mulcahey 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Bedbrook 2013, p. 153.

- ↑ Fink, Pfaff & Levine 2011, p. 559.

- ↑ Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 124.

- ↑ Jump up to: 114.0 114.1 Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 138.

- ↑ Jump up to: 115.0 115.1 The Mayo Clinic 2011, p. 155.

- ↑ Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 137.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 235.

- ↑ Jump up to: 118.0 118.1 Monga 2007, p. 473.

- ↑ Jump up to: 119.0 119.1 119.2 Sabharwal 2013, p. 309.

- ↑ Alpert & Wisnia 2009, p. 144.

- ↑ Jump up to: 121.0 121.1 Anderson, K.D.; Borisoff, J.F.; Johnson, R.D.; Stiens, S.A.; Elliott, S.L. (2007). "The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population". Spinal Cord 45 (5): 328–37. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101977. PMID 17033620.

- ↑ Naftchi 2012, pp. 260–61.

- ↑ Naftchi 2012, p. 261.

- ↑ Naftchi 2012, p. 259.

- ↑ Jump up to: 125.0 125.1 Ohl & Bennett 2013.

- ↑ Jump up to: 126.0 126.1 Sabharwal 2013, p. 311.

- ↑ Elliott 2010b, p. 429.

- ↑ Jump up to: 128.0 128.1 128.2 128.3 128.4 128.5 Burns, S.M.; Mahalik, J.R.; Hough, S.; Greenwell, A.N. (2008). "Adjustment to Changes in Sexual Functioning Following Spinal Cord Injury: The Contribution of Men's Adherence to Scripts for Sexual Potency". Sexuality and Disability 26 (4): 197–205. doi:10.1007/s11195-008-9091-y. ISSN 0146-1044.

- ↑ Courtois & Charvier 2015, p. 232.

- ↑ Hammell 2013, p. 79.

- ↑ Kraft, R.; Dorstyn, D. (2015). "Psychosocial correlates of depression following spinal injury: A systematic review". Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 38 (5): 571–83. doi:10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000295. PMID 25691222.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 337.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 352.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, pp. 352–53.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 354.

- ↑ Neumann 2013, p. 359.

- ↑ Jump up to: 137.0 137.1 Neumann 2013, p. 336.

- ↑ Hammell 2013, p. 295.

- ↑ Sabharwal 2013, pp. 311, 406.

- ↑ Kohut et al. 2015, p. 1521.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 153.

- ↑ Hammell 2013, p. 292.

- ↑ Florante & Leyson 2013, p. 366.

- ↑ Jump up to: 144.0 144.1 Livneh, Chan & Kaya 2013, p. 98.

- ↑ Livneh, Chan & Kaya 2013, p. 113.

- ↑ Kennedy & Smithson 2012, p. 209.

- ↑ Jump up to: 147.0 147.1 Miller & Marini 2012, pp. 136–37.

- ↑ Pfefferman, N. (11 June 2012). "Women in wheelchairs push boundaries in real life and on TV". The Times of Israel. http://www.timesofisrael.com/women-in-wheelchairs-push-boundaries-in-real-life-and-on-tv/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 149.0 149.1 149.2 Francoeur 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Hammell 2013, pp. 288–89.

- ↑ Taylor, V. (9 October 2014). "'Raw Beauty Project' celebrates women with disabilities". NY Daily News. http://www.nydailynews.com/life-style/raw-beauty-project-celebrates-women-disabilities-article-1.1969128.

- ↑ Panzarino 2013, p. 383.

- ↑ Peter, C.; Müller, R.; Cieza, A.; Geyh, S. (2011). "Psychological resources in spinal cord injury: A systematic literature review". Spinal Cord 50 (3): 188–201. doi:10.1038/sc.2011.125. ISSN 1362-4393. PMID 22124343.

- ↑ Jump up to: 154.0 154.1 Burns, S.M.; Hough, S.; Boyd, B.L.; Hill, J. (2009). "Sexual Desire and Depression Following Spinal Cord Injury: Masculine Sexual Prowess as a Moderator". Sex Roles 61 (1): 120–29. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9615-7. ISSN 0360-0025.

Bibliography

- Alpert, M.J.; Wisnia, S. (30 June 2009). Spinal Cord Injury and the Family: A New Guide. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02017-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=TUR_WroMzCMC&pg=PA318.

- Bedbrook, G.M. (29 June 2013). The Care and Management of Spinal Cord Injuries. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4613-8087-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=YY61BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA159.

- International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94190/1/9789241564663_eng.pdf. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Courtois, F.; Charvier, K. (21 May 2015). "Sexual dysfunction in patients with spinal cord lesions". in Vodusek, D.B.. Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders: Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 130. Elsevier Science. pp. 225–245. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00013-4. ISBN 978-0-444-63254-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=MBOdBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA225.

- Creasey, G.H.; Craggs, M.D. (31 December 2012). "Functional electrical stimulation for bowel, bladder, and sexual function". Spinal Cord Injury: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Series. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-444-53507-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8TL9IIs0OZMC&pg=PA224.

- Ditunno, J.F.; Cardenas, D.D.; Formal, C.; Dalal, K. (31 December 2012). "Advances in the rehabilitation management of acute spinal cord injury". Spinal Cord Injury: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Series. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-444-53507-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8TL9IIs0OZMC&pg=PA224.

- Daroff, R.B.; Fenichel, G.M.; Jankovic, J.; Mazziotta, J.C. (29 March 2012). Neurology in Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-2807-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=mpnaPQd_fZsC&pg=PT4560.

- Elliott, S. (26 March 2009). "Sexuality after spinal cord injury". in Field-Fote, E.. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. F.A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-2319-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=SRRhAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA527.

- Elliott, S. (19 March 2010). "Sexual dysfunction and infertility in men with spinal cord injury". in Bono, C.M.. Spinal Cord Medicine, Second Edition: Principles & Practice. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-935281-77-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=I2n5hTAxdTYC&pg=PT1521.

- Elliott, S. (19 March 2010). "Sexual dysfunction in women with spinal cord injury". in Bono, C.M.. Spinal Cord Medicine, Second Edition: Principles & Practice. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-935281-77-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=I2n5hTAxdTYC&pg=PT1521.

- Elliott, S. (29 October 2012). "Sexuality and fertility after spinal cord injury". in Fehlings, M.G.. Essentials of Spinal Cord Injury: Basic Research to Clinical Practice. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-60406-727-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=aQC-sQOCzhQC.

- Field-Fote, E. (26 March 2009). "Spinal cord injury: An overview". in Field-Fote, E.. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. F.A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-2319-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=SRRhAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA527.

- Fink, G.; Pfaff, D.W.; Levine, J. (31 August 2011). Handbook of Neuroendocrinology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-378554-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Disx7IryLxUC&pg=PA559.

- Florante, J.; Leyson, J.F.J. (9 March 2013). "Male homosexuality and other varieties of sexual lifestyles". in Leyson, J.F.J.. Sexual Rehabilitation of the Spinal-Cord-Injured Patient. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0467-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=20PtBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- Kohut, R.M.; Seftel, A.D.; Ducharme, S.H.; Fogel, B.S.; Bodner, D.R. (30 July 2015). "Sexual and psychological aspects of rehabilitation after spinal cord injury". Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-022629-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=xUH9CQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1524.

- Francoeur, R. (9 March 2013). "Cross-cultural and religious perspectives". in Leyson, J.F.J.. Sexual Rehabilitation of the Spinal-Cord-Injured Patient. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0467-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=20PtBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- Hammell, K.W. (11 December 2013). Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4899-4451-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=sVn5BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA289.

- Harvey, L. (2008). Management of Spinal Cord Injuries: A Guide for Physiotherapists. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-443-06858-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=FujsWb3H2UEC&pg=PA30. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Kennedy, P. (12 March 2007). Psychological Management of Physical Disabilities: A Practitioner's Guide. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-44984-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=iwqOAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA96.

- Kennedy, P.; Smithson, E.F. (29 October 2012). "Psychosocial aspects of spinal cord injury". in Fehlings, M.G.. Essentials of Spinal Cord Injury: Basic Research to Clinical Practice. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-60406-727-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=aQC-sQOCzhQC.

- Livneh, H.; Chan, F.; Kaya, C. (1 December 2013). "Stigma related to physical and sensory disabilities". in Corrigan, P.W.. The Stigma of Disease and Disability: Understanding Causes and Overcoming Injustices. American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1-4338-1583-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=DfnYngEACAAJ.

- The Mayo Clinic (May 2011). Mayo Clinic's Guide to Living with a Spinal Cord Injury. ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 978-1-4587-5865-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=LHz1REXsYKwC&pg=PA135.

- McKay-Moffat, S.F. (10 October 2007). "The interaction between specific conditions and the childbirth continuum". in McKay-Moffat, S.F.. Disability in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7020-3967-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=G52WNEKV7ckC&pg=PA176.

- Miller, E.; Marini, I. (24 February 2012). "Sexuality and spinal cord injury counseling implications". in Marini, I.. The Psychological and Social Impact of Illness and Disability, 6th Edition. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8261-0655-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=gWCkby69fXAC&pg=PA148.

- Monga, M. (22 May 2007). "Treatment of sexual dysfunction in men with spinal cord injury and other neurologic disabling disorders". in Kandeel, F.R.. Male Sexual Dysfunction: Pathophysiology and Treatment. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-1508-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Rl7d9EYm5CAC&pg=PA479.

- Naftchi, N.E. (6 December 2012). Spinal Cord Injury. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-011-6305-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=q3rvCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA259.

- Neumann, R.J. (9 March 2013). "The forgotten others: Partners of the spinal-cord-injured". in Leyson, J.F.J.. Sexual Rehabilitation of the Spinal-Cord-Injured Patient. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0467-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=20PtBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- Ohl, D.A.; Bennett, C.J. (29 June 2013). "Sexual and fertility concerns: Surgical practices". in Parsons K.F.. Practical Urology in Spinal Cord Injury. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4471-1860-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=mqGvBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT134.

- Panzarino, C.J. (9 March 2013). "Female homosexuality". in Leyson, J.F.J.. Sexual Rehabilitation of the Spinal-Cord-Injured Patient. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0467-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=20PtBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

- Sabharwal, S. (10 December 2013). Essentials of Spinal Cord Medicine. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61705-075-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=uaJdAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA35.

- Vogel, L.C.; Betz, R.R.; Mulcahey, M.J. (31 December 2012). "Spinal cord injuries in children and adolescents". Spinal Cord Injury: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Series. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-444-53507-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8TL9IIs0OZMC&pg=PA224.

- Wegener, S.T.; Adams, L.L.; Rohe, D. (31 December 2012). "Promoting optimal functioning in spinal cord injury: The role of rehabilitation psychology". Spinal Cord Injury: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Series. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-444-53507-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8TL9IIs0OZMC&pg=PA224.

- Wein, A.J.; Kavoussi, L.R.; Novick, A.C.; Partin, A.W.; Peters, C.A. (28 September 2011). Campbell-Walsh Urology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-2298-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=W1aeyJD46kIC&pg=PA643.

- Whipple, B. (9 March 2013). "Female sexuality". in Leyson, J.F.J.. Sexual Rehabilitation of the Spinal-Cord-Injured Patient. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-0467-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=20PtBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA339.

External links

- SCI Forum Reports: Dating and Relationships after SCI. University of Washington

- Sexuality & Sexual Function following SCI. University of Alabama at Birmingham Spinal Cord Injury Model System video series

- Sexuality and spinal cord injury: Where we are and where we are going. The Free Library

- Sexuality in Spinal Cord Injury. University of Miami School of Medicine

|