Medicine:Tinea corporis

| Tinea corporis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ringworm,[1] tinea circinata,[2] tinea glabrosa[1] |

| |

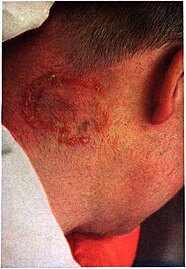

| This patient presented with ringworm on the arm, or tinea corporis due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes. | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Tinea corporis is a fungal infection of the body, similar to other forms of tinea. Specifically, it is a type of dermatophytosis (or ringworm) that appears on the arms and legs, especially on glabrous skin; however, it may occur on any superficial part of the body.

Signs and symptoms

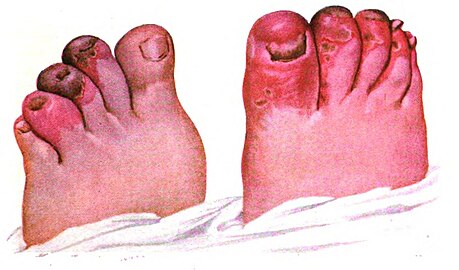

It may have a variety of appearances; most easily identifiable are the enlarging raised red rings with a central area of clearing (ringworm).[3] The same appearances of ringworm may also occur on the scalp (tinea capitis), beard area (tinea barbae) or the groin (tinea cruris, known as jock itch or dhobi itch).[citation needed]

Other classic features of tinea corporis include:[citation needed]

- Itching occurs on infected area.

- The edge of the rash appears elevated and is scaly to touch.

- Sometimes the skin surrounding the rash may be dry and flaky.

- Almost invariably, there will be hair loss in areas of the infection.[4]

Causes

Tinea corporis is caused by a tiny fungus known as dermatophyte. These tiny organisms normally live on the superficial skin surface, and when the opportunity is right, they can induce a rash or infection.[5]

The disease can also be acquired by person-to-person transfer usually via direct skin contact with an infected individual.[3] Animal-to-human transmission is also common. Ringworm commonly occurs on pets (dogs, cats) and the fungus can be acquired while petting or grooming an animal. Ringworm can also be acquired from other animals such as horses, pigs, ferrets, and cows. The fungus can also be spread by touching inanimate objects like personal care products, bed linen, combs, athletic gear, or hair brushes contaminated by an affected person.[3]

Individuals at high risk of acquiring ringworm include those who:[citation needed]

- Live in crowded, humid conditions.

- Sweat excessively, as sweat can produce a humid wet environment where the pathogenic fungi can thrive. This is most common in the armpits, groin creases and skin folds of the abdomen.

- Participate in close contact sports like soccer, rugby, or wrestling.

- Wear tight, constrictive clothing with poor aeration.

- Have a weakened immune system (e.g., those infected with HIV or taking immunosuppressive drugs).

Diagnosis

Superficial scrapes of skin examined underneath a microscope may reveal the presence of a fungus. This is done by utilizing a diagnostic method called KOH test,[6] wherein the skin scrapings are placed on a slide and immersed on a dropful of potassium hydroxide solution to dissolve the keratin on the skin scrappings thus leaving fungal elements such as hyphae, septate or yeast cells viewable. If the skin scrapings are negative and a fungus is still suspected, the scrapings are sent for culture. Because the fungus grows slowly, the culture results do take several days to become positive.[citation needed]

Prevention

Because fungi prefer warm, moist environments, preventing ringworm involves keeping skin dry and avoiding contact with infectious material. Basic prevention measures include:[citation needed]

- Washing hands after handling animals, soil, and plants.

- Avoiding touching characteristic lesions on other people.

- Wearing loose-fitting clothing.

- Practicing good hygiene when participating in sports that involve physical contact with other people.[5]

Treatment

Most cases are treated by application of topical antifungal creams to the skin, but in extensive or difficult to treat cases, systemic treatment with oral medication may be required. The over-the-counter options include tolnaftate, as well as ketoconazole (available as Nizoral shampoo that can be applied topically).[citation needed]

Among the available prescription drugs, the evidence is best for terbinafine and naftifine, but other agents may also work.[7]

Topical antifungals are applied to the lesion twice a day for at least 3 weeks. The lesion usually resolves within 2 weeks, but therapy should be continued for another week to ensure the fungus is completely eradicated. If there are several ringworm lesions, the lesions are extensive, complications such as secondary infection exist, or the patient is immunocompromised, oral antifungal medications can be used. Oral medications are taken once a day for 7 days and result in higher clinical cure rates. The antifungal medications most commonly used are itraconazole, terbinafine, and ketoconazole.[5][8]

The benefits of the use of topical steroids in addition to an antifungal is unclear.[7] There might be a greater cure rate but no guidelines currently recommend its addition.[7] The effect of Whitfield's ointment is also unclear.[7]

Prognosis

Tinea corporis is moderately contagious and can affect both humans and pets. If a person acquires it, the proper measures must be taken to prevent it from spreading. Young children in particular should be educated about the infection and preventive measures: avoid skin to skin contact with infected persons and animals, wear clothing that allows the skin to breathe, and do not share towels, clothing or combs with others. If pets are kept in the household or premises, the animal should be checked for tinea,[9] especially if hair loss in patches is noticed or the pet is scratching excessively. The majority of people who have acquired tinea know how uncomfortable the infection can be. However, the fungus can easily be treated and prevented in individuals with a healthy immune system.[4][8]

Society and culture

When the dermatophytic infection presents in wrestlers, with skin lesions typically found on the head, neck, and arms it is sometimes called tinea corporis gladiatorum.[10][11]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bolognia, Jean; Jorizzo, Joseph L.; Rapini, Ronald P. (2007). Dermatology (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier. p. 1135. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1. OCLC 212399895. https://archive.org/details/dermatologyvolum00mdje.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; Elston, Dirk M.; Odom, Richard B. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-8089-2351-0. OCLC 62736861. https://archive.org/details/andrewsdiseasess00mdwi_659.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Likness, LP (June 2011). "Common dermatologic infections in athletes and return-to-play guidelines.". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 111 (6): 373–379. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2011.111.6.373. PMID 21771922.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Berman, Kevin (2008-10-03). "Tinea corporis - All Information". Multi Media Medical Encyclopedia. University of Maryland Medical Center. http://www.umm.edu/ency/article/000877all.htm. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Brannon, Heather (2010-03-08). "Ringworm - Tinea Corporis". About.com Dermatology. About.com. http://dermatology.about.com/cs/fungalinfections/a/ringworm.htm.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Skin lesion KOH exam

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 El-Gohary, M; van Zuuren, EJ; Fedorowicz, Z; Burgess, H; Doney, L; Stuart, B; Moore, M; Little, P (Aug 4, 2014). "Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8 (8): CD009992. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2. PMID 25090020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gupta, Aditya K.; Chaudhry, Maria; Elewski, Boni (July 2003). "Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea nigra, and piedra". Dermatologic Clinics 21 (3): 395–400. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(03)00031-7. ISSN 0733-8635. OCLC 8649114. PMID 12956194.

- ↑ "Fungus Infections: Tinea". Dermatologic Disease Database. American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. http://aocd.org/skin/dermatologic_diseases/fungus_infections.html.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ Adams BB (August 2002). "Tinea corporis gladiatorum". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 47 (2): 286–90. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120603. PMID 12140477.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|