Organization:Technical University of Berlin

Technische Universität Berlin | |

| |

| Motto | Wir haben die Ideen für die Zukunft (German) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | We've got the brains for the future[1] |

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1770 (Königliche Bergakademie zu Berlin)

1799 (Königliche Bauakademie zu Berlin) 1879 (Königlich Technische Hochschule zu Berlin) 1946 as Technische Universität Berlin |

| Budget | €492,1 million (2017)[2] |

| President | Christian Thomsen (since 2014) |

Academic staff | 3,120[3] |

Administrative staff | 2,258[3] |

| Students | 34,428[3] |

| Location | , , [ ⚑ ] : 52°30′43″N 13°19′35″E / 52.51194°N 13.32639°E |

| Campus | Urban |

| Affiliations | TIME, TU9, EUA, CESAER, DFG, SEFI, PEGASUS, German Excellence Initiative, Berlin University Alliance |

| Website | www.tu-berlin.de |

The Technical University of Berlin (official name German: Technische Universität Berlin, known as TU Berlin, which has no official English translation[4]) is a research university located in Berlin, Germany . It is Germany’s first university to adopt the name “Technische Universität” (Technical University).[5]

The university alumni and professor list include US National Academies members,[6] two National Medal of Science laureates[7][8] and seven Nobel Prize winners.[9][10][11]

The TU Berlin is a member of TU9, an incorporated society of the largest and most notable German institutes of technology and of the Top Industrial Managers for Europe network,[12] which allows for student exchanges between leading engineering schools. It belongs to the Conference of European Schools for Advanced Engineering Education and Research.[13] The TU Berlin is home of two innovation centers designated by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology. The university is labeled as "The Entrepreneurial University" („Die Gründerhochschule“) by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.[14][15] It is also a member of the Berlin University Alliance.[16]

The university is notable for having been the first to offer the course Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen (which the institute itself translates as Industrial Engineering and Management). The university had conceptualised the course as a response to demands by industrialists to offer a course that provides their offspring with the technical and management expertise to run a company. First offered in winter term 1926/27, it is one of the oldest programmes of its kind.[17]

TU Berlin has one of the highest proportions of international students in Germany, in 2018 almost 24% of international students were enrolled.

History

On 1 April 1879, the Königlich Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg ("TH Charlottenburg") was formed by the governmental merger of the Berlin Building Academy (Königliche Bauakademie, founded in 1799) and the Royal Trade Academy (Königliche Gewerbeakademie, founded in 1827), two predecessor institutions of the Prussian State.

The TH Charlottenburg (Royal Technical Higher School of Charlottenburg) was named after the borough Charlottenburg where it is situated just outside Berlin. In 1899, the TH Charlottenburg was the first polytechnic in Germany to award doctorates, as a standard degree for the graduates, in addition to diplomas, thanks to professor Alois Riedler and Adolf Slaby, chairman of the Association of German Engineers (VDI) and the Association for Electrical, Electronic and Information Technologies (VDE).

In 1916 the long-standing Bergakademie Berlin, the Prussian mining academy created by the geologist Carl Abraham Gerhard in 1770 at the behest of King Frederick the Great, was assimilated into the TH Charlottenburg as the "Department of Mining" of the TH. Beforehand, the mining college had been, however, for several decades under the auspices of the Frederick William University (now Humboldt University of Berlin), before it was spun out again in 1860.

After Charlottenburg's absorption into Greater Berlin in 1920 and Germany being turned into Weimar Republic, the TH Charlottenburg was renamed "Technische Hochschule of Berlin" ("TH Berlin"). In 1927, the Department of Geodesy of the Agricultural College of Berlin was incorporated into the TH Berlin. During the 1930s, the redevelopment and expansion of the campus along the "East-West axis" were part of the Nazi plans of a Welthauptstadt Germania, including a new faculty of defense technology under General Karl Becker, built as a part of the greater academic town (Hochschulstadt) in the adjacent west-wise Grunewald forest. The shell construction remained unfinished after the outbreak of World War II and after Becker's suicide in 1940, it is today covered by the large-scale Teufelsberg dumping.

The north section of the main building of the university was destroyed during a bombing raid in November 1943.[18] Due to the street fighting at the end of the Second World War, the operations at the TH Berlin were suspended as of 20 April 1945. Planning for the re-opening of the school began on 2 June 1945, once the acting rectorship led by Gustav Ludwig Hertz and Max Volmer was appointed. As both Hertz and Volmer remained in exile in the Soviet Union for some time to come, the college was not re-inaugurated until 9 April 1946, now bearing the name of "Technische Universität Berlin".

Since 2009 the TU Berlin houses two Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KIC) designated by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology.[19]

Campus

The TU Berlin covers 604,000 m², distributed over various locations in Berlin. The main campus is located in the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. The seven schools of the university have some 33,933 students enrolled in 90 subjects (October, 2015).[20]

El Gouna campus: Technische Universität Berlin has established a satellite campus in Egypt to act as a scientific and academic field office. The nonprofit public–private partnership (PPP) aims to offer services provided by Technische Universität Berlin at the campus in El Gouna on the Red Sea.[21]

The university also has a franchise of its Global Production Engineering course - called Global Production Engineering and Management at the Vietnamese-German University in Ho Chi Minh City.[22][23]

Organization

Since 4 April 2005, the TU Berlin has consisted of the following faculties and institutes:

- Faculty I - Geisteswissenschaften[24]

- Institute of philosophy, history of literature, science and technology

- Institute of art history and historical urbanism

- Institute of pedagogy

- Institute of language and communication

- Institute of vocational education and employment studies

- Center for Research on Antisemitism

- Center of gender studies

- Faculty II - Mathematics and natural sciences[25]

- Institute of chemistry

- Institute of mathematics

- physical institutes

- Institute of solid-state physics

- Institute of optics and atomic physics

- Institute of theoretical physics

- Center of astronomy and astrophysics

- Faculty III - Process sciences and engineering[26]

- Institute of biotechnology

- Institute of energy engineering

- Institute of food technology and food chemistry

- Institute of process and methods engineering

- Institute of environmental technology

- Institute of materials science

- Faculty IV - Electrical engineering and computer science[27]

- Institute of energy engineering end automation engineering

- Institute of high-frequency and semiconductor system technology

- Institute of telecommunications systems

- Institute of computer engineering and microelectronics

- Institute of software engineering and theoretical computer science

- Institute of business informatics and quantitative methods

- Faculty V - Mechanical engineering and transport systems

- Institute of fluid mechanics and engineering acoustics

- Institute of psychology and human factors and ergonomics (Arbeitswissenschaft)

- Institute of surface transport (Land- und Seeverkehr)

- Institute of aerospace

- Institute of construction, microtechnology and medical engineering

- Institute of machine tools and factory management

- Institute of engineering mechanics

- Faculty VI - Planning – building – environment[28] (merge of former faculties of "civil engineering and applied geosciences" and "architecture – environment – society")

- Institute of architecture

- Institute of civil engineering

- Institute of applied geoscience

- Institute of geodesy and geographic data and information technology (Geoinformationstechnik)

- Institute of landscape architecture and environmental planning

- Institute of ecology

- Institute of sociology

- Institute of urban and regional planning

- Faculty VII - Economics and management[29]

- Institute of technology and management

- Institute of business administration (Betriebswirtschaftslehre)

- Institute of economics (Volkswirtschaftslehre) and business law

- Zentralinstitut El Gouna[30]

Faculty and staff

Eight-thousand four hundred fifty five people work at the university: 338 professors, 2,598 postgraduate researchers, and 2,131 personnel work in administration, the workshops, the library and the central facilities. In addition there are 2,651 student assistants and 126 trainees (2015).[31]

International student mobility is applicable through ERASMUS programme or through Top Industrial Managers for Europe (TIME) network.

Library

The new common main library of Technische Universität Berlin and of the Berlin University of the Arts was opened in 2004[32] and holds about 2.9 million volumes (2007).[33] The library building was sponsored partially (estimated 10% of the building costs) by Volkswagen and is named officially "University Library of the TU Berlin and UdK (in the Volkswagen building)".[34] A source of confusion to many, the letters above the main entrance only state "Volkswagen Bibliothek" (German for "Volkswagen Library") – without any mentioning of the universities.

Some of the former 17 libraries of Technische Universität Berlin and of the nearby University of the Arts were merged into the new library, but several departments still retain libraries of their own. In particular, the school of 'Economics and Management' maintains a library with 340,000 volumes in the university's main building (Die Bibliothek – Wirtschaft & Management/″The Library″ – Economics and Management) and the 'Department of Mathematics' maintains a library with 60,000 volumes in the Mathematics building (Mathematische Fachbibliothek/"Mathematics Library").

Notable alumni and professors

(Including those of the Academies mentioned under History)

- Bruno Ahrends (1878–1948), architect

- Steffen Ahrends (1907–1992), architect

- Stancho Belkovski (1891–1962), Bulgarian architect, head of Higher Technical School in Sofia and the department of public buildings.

- August Borsig (1804–1854), businessman

- Carl Bosch (1874–1940), chemist, Nobel prize winner 1931

- Franz Breisig (1868–1934), mathematician, inventor of the calibration wire and father of the term quadripole network in electrical engineering.

- Wilhelm Cauer (1900–1945), mathematician, essential contributions to the design of filters.

- Henri Marie Coandă (1886–1972), aircraft designer; discovered the Coandă Effect.

- Carl Dahlhaus (1928–1989), musicologist.

- George de Hevesy (1885–1966), chemist, Nobel prize winner 1943

- Walter Dornberger (1895–1980), developer of the Air Force-NASA X-20 Dyna-Soar project.

- Ottmar Edenhofer (born 1961), economist

- Krafft Arnold Ehricke (1917–1984), rocket-propulsion engineer, worked for the NASA, chief designer of the Centaur

- Gerhard Ertl (* 10. Oktober 1936 in Stuttgart) Physicist and Surface Chemist, Hon. Prof. and Nobel prize winner 2007

- Gottfried Feder (1883-1941), economist and key member of the National Socialist Party

- Wigbert Fehse (born 1937) German engineer and researcher in the area of automatic space navigation, guidance, control and docking/berthing.

- Dennis Gabor (1900–1971), physicist (holography), Nobel prize winner 1971

- Fritz Gosslau (1898–1965), German engineer, known for his work at the V-1 flying bomb.

- Fritz Haber (1868–1934), chemist, Nobel prize winner 1918.

- Sabine Hark (born 7 August 1962), sociologist and professor of gender studies

- Gustav Ludwig Hertz (1887–1975), physicist, Nobel prize winner 1925

- Olga Holtz (born 1973), mathematician

- Fritz Houtermans (1903–1966) atomic and nuclear physicist

- Hugo Junkers (1859–1935), former of Junkers & Co, a major German aircraft manufacturer.

- Anatol Kagan (1913-2009), Russian-born Australian architect.

- Helmut Kallmeyer (1910–2006), German chemist and Action T4 perpetrator

- Walter Kaufmann (1871–1947), physicist, well known for his first experimental proof of the velocity dependence of mass.

- Diébédo Francis Kéré (born 1965), architect

- Nicolas Kitsikis (1887-1978), Greek civil engineer, rector of the Athens Polytechnic School, senator and member of the Greek Parliament, doctor honoris causa of the Technical University of Berlin.

- Heinz-Hermann Koelle(*1925) former director of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, member of the launch crew on Explorer I and later directed the NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center's involvement in Project Apollo.

- Hans-Georg Münzberg (1916–2000), airflight propulsion (Luftfahrtriebwerke)

- Abdul Qadeer Khan(*1936), Pakistani nuclear physicist and metallurgical engineer, who founded the uranium enrichment program for Pakistan's atomic bomb project.[35]

- Franz Kruckenberg (1882–1965), designer of the first aerodynamic high-speed train 1931

- Karl Küpfmüller (1897–1977), electrical engineer, essential contributions to system theory

- Wassili Luckhardt (1889–1972), architect

- Georg Hans Madelung (1889–1972), a German academic and aeronautical engineer.

- Herbert Franz Mataré (1912-2011), German physicist and Transistor-pioneer

- Alexander Meissner (1883–1958), electrical engineer

- Joachim Milberg (*1943), Former CEO of BMW AG.

- Erwin Wilhelm Müller (1911–1977), physicist (field emission microscope, field ion microscope, atom probe)

- Hans-Georg Münzberg (1916–2000), engineer, airplane turbines

- Gustav Niemann (1899 – 1982), mechanical engineer

- Ida Noddack (1896–1978), nominated three times for Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- Jakob Karol Parnas (1884–1949), biochemist, Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway

- Wolfgang Paul (1913–1993), physicist, Nobel prize winner 1989

- Franz Reuleaux (1829–1905), mechanical engineer, often called the father of kinematics

- Klaus Riedel (1907–1944), German rocket pioneer, worked on the V-2 missile programme at Peenemünde.

- Alois Riedler (1850–1936), inventor of the Leavitt-Riedler Pumping Engine; proponent of practically-oriented engineering education.

- Hermann Rietschel (1847-1914), inventor of modern HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning).

- Arthur Rudolph (1906–1996) worked for the U.S. Army and NASA, developer of Pershing missile and the Saturn V Moon rocket.

- Ernst Ruska (1906–1988), physicist (electron microscope), Nobel prize winner 1986

- Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841), architect (at the predecessor Berlin Building Academy)

- Eckehard Schöll (*1951 in Stuttgart), physicist and mathematician

- Cindy Shih, artist

- Adolf Slaby (1849–1913), German wireless pioneer

- Albert Speer (1905–1981), architect, politician, Minister for Armaments during the Third Reich, was sentenced to 20 years prison in the Nuremberg trials

- Ivan Stranski (1897–1979), chemist, considered the father of crystal growth research

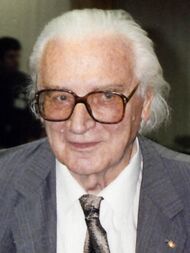

- Ernst Stuhlinger (1913–2008), member of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, director of the space science lab at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center.

- Kurt Tank (1893–1983), head of design department of Focke-Wulf, designed the Fw 190

- Hermann W. Vogel, (1834–1898) photo-chemist

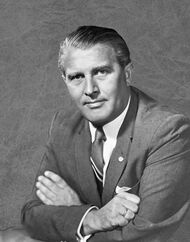

- Wernher von Braun (1912–1977), head of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket program, saved from prosecution at the Nuremberg Trials by Operation Paperclip, first director of the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Marshall Space Flight Center, called the father of the U.S. space program.

- Elisabeth von Knobelsdorff (1877–1959), engineer and architect

- Wilhelm Heinrich Westphal (1882–1978), physicist

- Eugene Wigner (1902–1995), physicist, discovered the Wigner-Ville-distribution, Nobel prize winner 1963

- Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), philosopher

- Martin C. Wittig (*1964), Former CEO of the management consultant firm Roland Berger Strategy Consultants.

- Elisa Leonida Zamfirescu (1887-1973) chemist, graduated 1912, female engineering pioneer.

- Günter M. Ziegler (*1963), Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize (2001)

- Konrad Zuse (1910–1995), computer pioneer

Rankings

Template:Infobox world university ranking Measured by the number of top managers in the German economy, TU Berlin ranked 11th in 2019.[36]

According to the research report of the German Research Foundation from 2018, TU Berlin ranks 24th absolute among German universities across all scientific disciplines. Thereby TU Berlin ranks 9th absolute in natural sciences and engineering. The TU Berlin took 14th place absolute in computer science and 5th place absolute in electrical engineering.[37] In a competitive selection process, the DFG selects the best research projects from researchers at universities and research institutes and finances them. The ranking is thus regarded as an indicator of the quality of research.[38]

In the 2017 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, globally the TU Berlin ranks 82nd overall (7th in Germany), 40th in the field of Engineering & Technology (3rd in Germany) and 36th in Computer science discipline (4th in Germany), making it one of the top 100 universities worldwide in all three measures.[39]

As of 2016, TU Berlin is ranked 164th overall and 35th in the field of Engineering & Technology according to the British QS World University Rankings. It is one of Germany's highest ranked universities in statistics and operations research and in Mathematics according to QS.[40]

See also

- Universities and research institutions in Berlin

- European Institute of Innovation and Technology

- Berlin School of Economics and Law

- Freie Universität Berlin (Free University of Berlin)

- Hertie School of Governance

- Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (Humboldt University of Berlin)

- Universität der Künste (Berlin University of the Arts)

- Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (HTW Berlin University of Applied Sciences)

- Beuth Hochschule für Technik Berlin (Beuth University of Applied Sciences)

References

- ↑ "TU Berlin: About the TU Berlin". http://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/about_the_tu_berlin/parameter/en/. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Facts & Figures". https://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/about_the_tu_berlin/facts_figures/parameter/en/#c17816.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Facts & Figures". http://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/about_the_tu_berlin/facts_figures/parameter/en/. Retrieved 2017-06-14.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Impressum" (in de). https://www.tu-berlin.de/servicemenue/impressum/.

- ↑ "Die erste Technische Universität". https://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/ueber_die_tu_berlin/profil_geschichte/geschichte/#c7279.

- ↑ "National Academy of Sciences". http://www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Eugene Wigner - Biographical". http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1963/wigner-bio.html. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ Wernher von Braun

- ↑ "Gustav Hertz - Biographical". http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1925/hertz-bio.html. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Fritz Haber - Biographical". http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1918/haber-bio.html. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Carl Bosch - Biographical". http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1931/bosch-bio.html. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "T.I.M.E. Top Industrial Managers for Europe". https://www.time-association.org/members/. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ Brainlane - SiteLab CMS v2. "Germany". http://www.cesaer.org/en/members/germany/. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "EXIST competition guide". https://www.exist.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Leitfaden-Antrag-Gruendungshochschule-zweiter-Wettbewerb.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- ↑ "Fuer-Gruender 21 Entrepreneurial University". https://www.fuer-gruender.de/kapital/foerdermittel/zuschuss/exist-gruenderstipendium/exist-gruenderhochschulen.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Facts & Figures". https://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/about_the_tu_berlin/facts_figures/parameter/en/#c17816.

- ↑ Jens, Weibezahn (2016) (in de). Studienführer für den Studiengang Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen. Universitätsverlag der TU Berlin. doi:10.14279/depositonce-5501. ISBN 9783798328655. https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/handle/11303/5908.

- ↑ Entstehung und Bedeutung UNIVERSITÄTSBIBLIOTHEK Technische Universität Berlin. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "EIT ICT Labs - Turn Europe into a global leader in ICT Innovation". TU Berlin. https://www.entrepreneurship.tu-berlin.de/menue/masterprogramme_qualifizierung/eit_ict_labs/. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Facts & Figures". http://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/ueber_die_tu_berlin/zahlen_fakten/parameter/en/. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "TUB Campus El Gouna: Home". http://www.campus-elgouna.tu-berlin.de/. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "GPE Global Production Engineering: Home" (in en-EN). http://www.gpe.tu-berlin.de/index.php?id=3.

- ↑ "Global Production Engineering and Management". Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170322014551/http://www.vgu.edu.vn/studies/master/international-production-engineering-and-management/.

- ↑ I, FSC. "Fakultät I Geisteswissenschaften: Institute und Zentren / Professuren / Fachgebiete". http://www.tu-berlin.de/fakultaet_i/menue/einrichtungen/institute_und_zentren_professuren_fachgebiete/.

- ↑ "Fakultät II - Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften: Institute". http://www.naturwissenschaften.tu-berlin.de/menue/einrichtungen/institute/.

- ↑ "Fakultät III Prozesswissenschaften: Institute". http://www.tu-berlin.de/fak_3/menue/einrichtungen/institute/.

- ↑ Webmaster. "Fakultät IV Elektrotechnik und Informatik: Institute". http://www.eecs.tu-berlin.de/menue/einrichtungen/institute/.

- ↑ Lehre, Referat Studium und. "Fakultät VI Planen Bauen Umwelt: Institute". http://www.planen-bauen-umwelt.tu-berlin.de/menue/institute/.

- ↑ webmaster. "Fakultät VII Wirtschaft & Management: Einrichtungen". http://www.wm.tu-berlin.de/menue/einrichtungen/.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Fakultätsübersicht". Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170118164522/http://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/fakultaeten/.

- ↑ "TU Berlin: Facts & Figures". http://www.tu-berlin.de/menue/ueber_die_tu_berlin/zahlen_fakten/#91200. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ "Universitätsbibliothek TU Berlin: About Us". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120305152231/http://www.ub.tu-berlin.de/index.php?id=555#content10219. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ "Universitätsbibliothek TU Berlin: About Us". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120305152231/http://www.ub.tu-berlin.de/index.php?id=555#content2195. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ↑ Universitätsbibliothek der Technischen Universität Berlin. "Universitätsbibliothek TU Berlin: Startseite". Universitätsbibliothek TU Berlin. http://www.ub.tu-berlin.de/. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ (IISS), International Institute for Strategic Studies (2006). "Bhutto was father of Pakistan's Atom Bomb Program". International Institute for Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120314025504/http://www.iiss.org/whats-new/iiss-in-the-press/press-coverage-2007/may-2007/bhutto-was-father-of-pakistani-bomb/?locale=en. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ "An diesen Unis haben die DAX-Vorstände studiert | charly.education" (in de). https://www.charly.education/presse/dax-karriere.

- ↑ "Förderatlas 2018" (in German), Forschungsberichte (Weinheim: Wiley-VCH), 2018-07-18, ISBN 978-3-527-34520-5

- ↑ "Aufgaben der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)" (in Deutsch). https://www.dfg.de/dfg_profil/aufgaben/index.html.

- ↑ "The Times Higher Education World University Rankings". TU Berlin. 25 March 2019. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/technical-university-of-berlin#ranking-dataset/589595.

- ↑ "QS World University Ranking". Top Universities. 16 July 2015. https://www.topuniversities.com/universities/technische-universit%C3%A4t-berlin-tu-berlin.

External links

- (in German) Official Homepage

- (in English) Official Homepage

- (in German) Homepage of the Student's Council and Government

- Map of campus