Philosophy:Enlightenment (spiritual)

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Influences |

| Research |

Enlightenment is a concept found in several religions, including Buddhist terms and concepts, most notably bodhi,[note 1] kensho, and satori. It represents kaivalya and moksha (liberation) in Hinduism, Kevala Jnana in Jainism, and ushta in Zoroastrianism.

In Christianity, the word "enlightenment" is rarely used, except to refer to the Age of Enlightenment and its influence on Christianity. Roughly equivalent terms in Christianity may be illumination, kenosis, metanoia, revelation, salvation, theosis, and conversion.

Perennialists and Universalists view enlightenment and mysticism as equivalent terms for religious or spiritual insight.

Asian cultures and religions

Buddhism

The English term enlightenment is the western translation of the abstract noun bodhi, the knowledge, wisdom, or awakened intellect of a Buddha.[web 1] The verbal root, Budh, derived from Vedic Sanskrit, means "to awaken" or "awakening."

Enlightenment is also used to translate several other Buddhist terms and concepts, which are used to denote insight (prajna, kensho and satori);[1] knowledge (vidhya); the "blowing out" (Nirvana) of disturbing emotions and desires and the subsequent freedom or release (vimutti); and the attainment of Buddhahood, as exemplified by Gautama Buddha. The Buddha’s awakening constituted the knowledge that liberation, attained by mindfulness and dhyāna, and applied to the understanding of the arising and ceasing of craving.

Although it is most commonly used in Buddhist contexts, the term buddhi is also used in other Indian philosophies and traditions.

The term "enlightenment" was popularized in the Western world through the 19th century translations of Max Müller. It has the western connotation of a sudden insight into a transcendental truth or reality. The concept of spiritual enlightenment has become synonymous with self-realization, or the recognition of the true self, regarded as the essence of being, and the seeing through of the false self, the layers of social conditioning which overcover the true self.[2][page needed], [3][page needed], [4][page needed], [5][page needed]

Hinduism

In Indian religions, moksha (Sanskrit: मोक्ष mokṣa; liberation) or mukti (Sanskrit: मुक्ति; release —both from the root muc "to let loose, let go") is the final extrication of the soul or consciousness (purusha) from samsara and the bringing to an end of all the suffering involved in being subject to the cycle of repeated death and rebirth (reincarnation).

Advaita Vedanta

Advaita Vedanta (IAST Advaita Vedānta; Sanskrit: अद्वैत वेदान्त [ɐdʋaitɐ ʋeːdaːntɐ]) is a philosophical concept where followers seek liberation by recognizing identity of the Self (Atman) and the Whole (Brahman) through long preparation, usually under the guidance of a guru. It involves efforts such as knowledge of scriptures, renunciation of worldly activities, and inducement of direct identity experiences. Ramana Maharshi, however, recalled his death experience as akrama mukti, "sudden liberation", as opposed to the krama mukti, "gradual liberation" as in the Vedanta path of Jnana yoga.

Neo-Advaita

Neo-Advaita is a new religious movement based on a modern, Western interpretation of Advaita Vedanta, especially the teachings of Ramana Maharshi.[6] Neo-Advaita is being criticized[7][note 2][8][note 3][note 4] for discarding the traditional prerequisites of knowledge of the scriptures[9] and naming "renunciation as necessary preparation for the path of jnana-yoga".[9][10] Notable neo-advaita teachers are H. W. L. Poonja,[11][6] his students Gangaji[12] Andrew Cohen,[note 5], Madhukar[14] and Eckhart Tolle.[6]

Neo-Vedanta

Vivekananda's interpretation of Advaita Vedanta has been called "Neo-Vedanta".[15] In Neo-Vedanta, samadhi is emphasized as a means to liberation.[16]

In a talk on "The absolute and manifestation" given in at London in 1896 Swami Vivekananda said,

I may make bold to say that the only religion which agrees with, and even goes a little further than modern researchers, both on physical and moral lines is the Advaita, and that is why it appeals to modern scientists so much. They find that the old dualistic theories are not enough for them, do not satisfy their necessities. A man must have not only faith, but intellectual faith too".[web 7]

Vivekananda's emphasis on samadhi is not to be found in the Upanishads nor in Shankara.[17] For Shankara, meditation and Nirvikalpa Samadhi are means to gain knowledge of the already existing unity of Brahman and Atman,[16] not the highest goal itself:

[Y]oga is a meditative exercise of withdrawal from the particular and identification with the universal, leading to contemplation of oneself as the most universal, namely, Consciousness. This approach is different from the classical yoga of complete thought suppression.[16]

Vivekenanda's modernisation has been criticized:[15][18]

Without calling into question the right of any philosopher to interpret Advaita according to his own understanding of it, [...] the process of Westernization has obscured the core of this school of thought. The basic correlation of renunciation and Bliss has been lost sight of in the attempts to underscore the cognitive structure and the realistic structure which according to Samkaracarya should both belong to, and indeed constitute the realm of māyā.[15]

Yoga

Moksha is also understood to be reached through the practice of yoga (Sanskrit, Pāli: योग, /ˈjəʊɡə/, yoga).[19][20] Yoga is one of the six āstika ("orthodox") schools of Hindu philosophy. Various traditions of yoga are found in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism.[21][22][note 6]

Pre–philosophical speculations and diverse ascetic practices of first millennium BCE were systematized into a formal philosophy in early centuries CE by the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[24] By the turn of the first millennium, Hatha yoga emerged as a prominent tradition of yoga distinct from the Patanjali's Yoga Sutras. While the Yoga Sutras focus on discipline of the mind, Hatha yoga concentrates on health and purity of the body.[25]

In the 1980s, yoga also became popular as a physical system of health exercises across the Western world. Many studies have tried to determine the effectiveness of yoga as a complementary intervention for cancer, schizophrenia, asthma and heart patients. In a national survey, long-term yoga practitioners in the United States reported musculo–skeletal and mental health improvements.[26]

Jnana yoga

Classical Advaita Vedanta emphasises the path of jnana yoga, a progression of study and training to attain moksha. It consists of four stages:[27][web 8]

- Samanyasa or Sampattis,[28] the "fourfold discipline" (sādhana-catustaya), cultivating the following four qualities:[27][web 9]

- Nityānitya vastu viveka (नित्यानित्य वस्तु विवेकम्) – The ability to correctly discriminate (viveka) between the eternal (nitya) substance (Brahman) and the substance that is transitory existence (anitya).

- Ihāmutrārtha phala bhoga virāga (इहाऽमुत्रार्थ फल भोगविरागम्) – The renunciation (virāga) of enjoyments of objects (artha phala bhoga) in this world (iha) and the other worlds (amutra) like heaven etc.

- Śamādi ṣatka sampatti (शमादि षट्क सम्पत्ति) – the sixfold qualities,

- Śama (control of the antahkaraṇa).[web 10]

- Dama (the control of external sense organs).

- Uparati (the cessation of these external organs so restrained, from the pursuit of objects other than that, or it may mean the abandonment of the prescribed works according to scriptural injunctions).[note 7]

- Titikṣa (the tolerating of tāpatraya).

- Śraddha (the faith in Guru and Vedas).

- Samādhāna (the concentrating of the mind on God and Guru).

- Mumukṣutva (मुमुक्षुत्वम्) – The firm conviction that the nature of the world is misery and the intense longing for moksha (release from the cycle of births and deaths).

- Sravana, listening to the teachings of the sages on the Upanishads and Advaita Vedanta, and studying the Vedantic texts, such as the Brahma Sutras. In this stage the student learns about the reality of Brahman and the identity of atman;

- Manana, the stage of reflection on the teachings;

- Dhyana, the stage of meditation on the truth "that art Thou".

Bhakti yoga

The paths of bhakti yoga and karma yoga are subsidiary. In bhakti yoga, practice centers on the worship of God, such as Krishna or Ayyappa, in any way and in any form. Adi Shankara, himself, was a proponent of devotional worship or Bhakti. He taught that while Vedic sacrifices, puja, and devotional worship can lead one in the direction of jnana (true knowledge), they cannot lead one directly to moksha. At best, they can serve as means to obtain moksha via shukla gati.[citation needed]

Karma yoga

Karma yoga is the way of doing our duties, in disregard of personal gains or losses, in an attempt to achieve moksha. According to Sri Swami Sivananda,

Karma Yoga is consecration of all actions and their fruits unto the Lord. Karma Yoga is performance of actions dwelling in union with the Divine, removing attachment and remaining balanced ever in success and failure. Karma Yoga is selfless service unto humanity. Karma Yoga is the Yoga of action which purifies the heart and prepares the Antahkarana (the heart and the mind) for the reception of Divine Light or attainment of Knowledge of the Self. The important point is that you will have to serve humanity without any attachment or egoism.[web 11]

Jainism

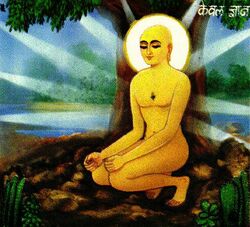

The philosophy and practice of Jainism (/ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/; Sanskrit: जैनधर्म Jainadharma, Tamil: சமணம் Samaṇam, Bengali: জৈনধর্ম Jainadharma, Telugu: జైనమతం Jainamataṁ, Malayalam: ജൈനമതം Jainmat, Kannada: ಜೈನ ಧರ್ಮ Jaina dharma) emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul toward divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its inner enemies and achieved the state of supreme being is called a jina ("conqueror" or "victor"). The ultimate status of these perfect souls is called siddha. Ancient texts also refer to Jainism as shramana dharma (self-reliant) or the "path of the nirganthas" (those without attachments or aversions). In Jainism, enlightenment is called as "Keval Gyan" and the one who atains it is known as a "Kevalin".

In Jainism, the highest form of pure knowledge a soul can attain is called Kevala Jnana (Sanskrit: केवलज्ञान) or Kevala Ṇāṇa (Prakrit: केवल णाण). Kevala means "absolute or perfect," and Jñāna, which means "knowledge". Kevala is the state of isolation of the jīva from the ajīva, attained through ascetic practices which burn off one's karmic residues, releasing one from bondage to the cycle of death and rebirth. Kevala Jñāna thus means infinite knowledge of self and non-self, attained by a soul after annihilation of the all ghātiyā karmas. The soul which has reached this stage achieves moksa or liberation at the end of its life span.

Mahavira, 24th tirthankara of Jainism, is said to have practised rigorous austerities for 12 years before he attained enlightenment,

Kevala Jñāna is one of the five major events in the life of a Tirthankara and is known as Keval Jñāna Kalyanaka and celebrated of all gods. Lord Mahavira's Kaivalya was said to have been celebrated by the demi-gods, who constructed the Samosarana or a grand preaching assembly for him.

Western understanding

In the Western world, the religious concept of enlightenment usually posits a romantic meaning. It has become synonymous with self-realization and the true self, which is being regarded as a substantial essence, covered over by social conditioning.[note 8]

As Aufklärung

The use of the Western word enlightenment is based on the supposed resemblance of bodhi with Aufklärung, the independent use of reason to gain insight into the true nature of our world. There are more resemblances with Romanticism than with the Enlightenment: the emphasis on feeling, on intuitive insight, and on a true essence beyond the world of appearances.[29]

Awakening: Historical period of renewed interest in religion

The term "awakening", equivalent to "enlightenment," has also been used in a Christian context,[30] namely the Great Awakenings, several periods of religious revival in American religious history. Historians and theologians identify three or four waves of increased religious enthusiasm occurring between the early 18th century and the late 19th century. Each of these "Great Awakenings" was characterized by widespread revivals led by evangelical Protestant ministers, a sharp increase of interest in religion, a profound sense of conviction and redemption on the part of those affected, an increase in evangelical church membership, and the formation of new religious movements and denominations.

Illumination

Another term for enlightenment is Illuminationism, used by Paul Demieville in his work The Mirror of the Mind, which raised distinctions between "illumination subie" and "illumination graduelle".[31][web 12] Illuminationism is a doctrine according to which the process of human thought needs to be aided by divine grace. It is the oldest and most influential alternative to naturalism in the theory of mind and epistemology.[web 13] It was an important feature of ancient Greek philosophy, Neoplatonism, medieval philosophy, and in particular, the Illuminationist school of Islamic philosophy.

Augustine was an important proponent of Illuminationism, stating that everything we know is taught to us by God as He casts His light over the world.[web 14] He states, "The mind needs to be enlightened by light from outside itself, so that it can participate in truth, because it is not itself the nature of truth. You will light my lamp, Lord," [32] and "You hear nothing true from me which you have not first told me."[33] Augustine's version of illuminationism is not that God gives us certain information, but rather gives us insight into the truth of the information we received for ourselves.

Romanticism and transcendentalism

The romantic idea of enlightenment as an insight into a timeless, transcendent reality has been popularized especially by D.T. Suzuki.[web 15][web 16] Further popularization was due to the writings of Heinrich Dumoulin.[34][35][web 17] Dumoulin viewed metaphysics as the expression of a transcendent truth expressed by Mahayana Buddhism, not by the pragmatic analysis of the oldest Buddhism, which emphasizes anatta.[36] This romantic vision is also recognizable in the works of Ken Wilber.[37]

In old Buddhism, this essentialism is not recognizable.[38][web 18] According to critics, it doesn't really contribute to a real insight into Buddhism:[web 19]

...most of them labour under the old cliché that the goal of Buddhist psychological analysis is to reveal the hidden mysteries in the human mind and thereby facilitate the development of a transcendental state of consciousness beyond the reach of linguistic expression.[39]

Experience

The notion of "enlightenment experience" is common in Western culture. This notion can be traced back to William James, who used the term "religious experience" in his book, The Varieties of Religious Experience.[40] Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" further back to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique.[4]

"Enlightenment experience" was also popularized by the Transcendentalists, and exported to Asia via missionaries.[41] Transcendentalism developed as a reaction against 18th-century rationalism, John Locke's philosophy of Sensualism, and the predestinationism of New England Calvinism. It is fundamentally a variety of diverse sources such as Hindu texts like the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita,[42] various religions, and German idealism.[43] It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential.[44][note 9]

The notion of "experience," however, has also been criticized.[3][48][49] Robert Sharf points out that "experience" is a typical Western term, which has found its way into Asian religiosity via western influences.[3][note 10] The notion of "experience" introduces a false notion of duality between "experiencer" and "experienced", whereas the essence of kensho is the realisation of the "non-duality" of observer and observed.[51][52] "Pure experience" does not exist; all experience is mediated by intellectual and cognitive activity.[53][54] The specific teachings and practices of a specific tradition may even determine what "experience" someone has, which means that this "experience" is not the proof of the teaching, but a result of the teaching.[55] A pure consciousness without concepts, reached by "cleansing the doors of perception",[note 11] would be an overwhelming chaos of sensory input without coherence.[56]

Nevertheless, the notion of religious experience has gained widespread use in the study of religion,[citation needed] and is extensively researched.[citation needed]

Western culture

Socrates to Platonism

Socrates' and Plato's dialogues discuss enlightenment, a large part of which is in the Republic: allegory of the cave.

Christianity

In Christian contexts, the word "enlightenment" is uncommon for religious understanding or insight. Instead, terms such as religious conversion and revelation are prevalent.

Lewis Sperry Chafer (1871–1952), one of the founders of Dispensationalism, uses the word "illuminism". Christians who are "illuminated" are of two groups, those who have experienced true illuminism (biblical) and those who experienced false illuminism (not from the Holy Spirit).[57]

Christian interest in eastern spirituality has grown throughout the 20th century. Notable Christians, such as Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle and AMA Samy, have participated in Buddhist training and even become Buddhist teachers themselves. In a few places, Eastern contemplative techniques have been integrated in Christian practices, such as centering prayer.[web 21] This integration has also raised questions about the borders between these traditions.[web 22]

Western esotericism and mysticism

Western and Mediterranean culture has a rich tradition of esotericism and mysticism.[58] The Perennial philosophy, basic to the New Age understanding of the world, regards those traditions as akin to Eastern religions which aim at enlightenment and developing wisdom. The hypothesis that all mystical traditions share a "common core"[59] is central to New Age but contested by a diversity of scientists like Katz and Proudfoot.[59]

Judaism includes the mystical tradition of Kabbalah. Islam includes the mystical tradition of Sufism. In the Fourth Way teaching, enlightenment is the highest state of Man (humanity).[60]

Nondualism

A popular western understanding sees "enlightenment" as "nondual consciousness", "a primordial, natural awareness without subject or object".[web 23] It is used interchangeably with Neo-Advaita.

This nondual consciousness is seen as a common stratum to different religions. Several definitions or meanings are combined in this approach, which makes it possible to recognize various traditions as having the same essence.[61] According to Renard, many forms of religion are based on an experiential or intuitive understanding of "the Real."[62]

This idea of nonduality as "the central essence"[63] is part of a modern mutual exchange and synthesis of ideas between western spiritual and esoteric traditions and Asian religious revival and reform movements.[note 12] Western predecessors are, among others, New Age,[58] Wilber's synthesis of western psychology and Asian spirituality, the idea of a Perennial Philosophy, and Theosophy. Eastern influences are the Hindu reform movements such as Aurobindo's Integral Yoga and Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta, the Vipassana movement, and Buddhist modernism. A truly syncretistic influence is Osho[64] and the Rajneesh movement, a hybrid of eastern and western ideas and teachings, and a mainly western group of followers.[65]

Cognitive aspects

Religious experience as cognitive construct

"Religious experiences" have "evidential value,"[66] since they confirm the specific worldview of the experiencer:[67][3][18]

These experiences are cognitive in that, allegedly at least, the subject of the experience receives a reliable and accurate view of what, religiously considered, are the most important features of things. This, so far as their religious tradition is concerned, is what is most important about them. This is what makes them "salvific" or powerful to save.[68]

Yet, just like the very notion of "religious experience" is shaped by a specific discourse and habitus, the "uniformity of interpretation"[citation needed] may be due to the influence of religious traditions which shape the interpretation of such experiences.[3][69][67]

Various religious experiences

Yandell discerns various "religious experiences" and their corresponding doctrinal settings, which differ in structure and phenomenological content, and in the "evidential value" they present.[70] Yandell discerns five sorts:[71]

- Numinous experiences – Monotheism (Jewish, Christian, Vedantic, Sufi Islam)[72]

- Nirvanic experiences – Buddhism,[73] "according to which one sees that the self is but a bundle of fleeting states"[74]

- Kevala experiences[75] – Jainism,[66] "according to which one sees the self as an indestructible subject of experience"[66]

- Moksha experiences[76] – Hinduism,[66] Brahman "either as a cosmic person, or, quite differently, as qualityless"[66]

- Nature mystical experience[75]

Cognitive science

Various philosophers and cognitive scientists state that there is no "true self" or a "little person" (homunculus) in the brain that "watches the show," and that consciousness is an emergent property that arises from the various modules of the brain in ways that are still far from understood.[77][78][79] According to Susan Greenfield, the "self" may be seen as a composite,[80] whereas Douglas R. Hofstadter describes the sense of "I" as a result of cognitive process.[81]

This is in line with the Buddhist teachings, which state that

[...] what we call 'I' or 'being,' is only a combination of physical and mental aggregates which are working together interdependently in a flux of momentary change within the law of cause and effect, and that there is nothing, permanent, everlasting, unchanging, and eternal in the whole of existence.[82]

To this end, Parfit called Buddha the "first bundle theorist".[83]

Entheogens

Several users of entheogens throughout the ages have claimed experiences of spiritual enlightenment. The use and prevalence of entheogens through history is well recorded and continues today. In modern times, we have seen increased interest in these practices, for example the rise of interest in Ayahuasca. The psychological effects of these substances have been subject to scientific research focused on understanding their physiological basis. While entheogens do produce glimpses of higher spiritual states, these are always temporary, fading with the effects of the substance. Permanent enlightenment requires making permanent changes in your consciousness.

See also

- Philosophy:Ego death – Complete loss of subjective self-identity

- Unsolved:Fana (Sufism) – Annihilation of self in Sufism

- Philosophy:Henosis – Classical Greek word for mystical oneness

- Religion:Light of Christ

- Philosophy:Merit (Buddhism) – Concept considered fundamental to Buddhist ethics

- Philosophy:Moral circle expansion

- Philosophy:Moral development – Emergence, change, and understanding of morality from infancy through adulthood

- Philosophy:Nous – Concept in classical philosophy

- Philosophy:Self-realization – Fulfillment of one's character or personality

- Philosophy:Soul flight – The concept of soul flight

Notes

- ↑ When referring to the Enlightenment of the Buddha (samma-sambodhi) and thus to the goal of the Buddhist path, the word enlightenment is normally translating the Pali and Sanskrit word bodhi

- ↑ Marek: "Wobei der Begriff Neo-Advaita darauf hinweist, dass sich die traditionelle Advaita von dieser Strömung zunehmend distanziert, da sie die Bedeutung der übenden Vorbereitung nach wie vor als unumgänglich ansieht. (The term Neo-Advaita indicating that the traditional Advaita increasingly distances itself from this movement, as they regard preparational practicing still as inevitable)[7]

- ↑ Alan Jacobs: Many firm devotees of Sri Ramana Maharshi now rightly term this western phenomenon as 'Neo-Advaita'. The term is carefully selected because 'neo' means 'a new or revived form'. And this new form is not the Classical Advaita which we understand to have been taught by both of the Great Self Realised Sages, Adi Shankara and Ramana Maharshi. It can even be termed 'pseudo' because, by presenting the teaching in a highly attenuated form, it might be described as purporting to be Advaita, but not in effect actually being so, in the fullest sense of the word. In this watering down of the essential truths in a palatable style made acceptable and attractive to the contemporary western mind, their teaching is misleading.[8]

- ↑ See for other examples Conway [web 2] and Swartz [web 3]

- ↑ Presently Cohen has distanced himself from Poonja, and calls his teachings "Evolutionary Enlightenment".[13] What Is Enlightenment, the magazine published by Cohen's organisation, has been critical of neo-Advaita several times, as early as 2001. See.[web 4][web 5][web 6]

- ↑ Tattvarthasutra [6.1][23]

- ↑ nivartitānāmeteṣāṁ tadvyatiriktaviṣayebhya uparamaṇamuparatirathavā vihitānāṁ karmaṇāṁ vidhinā parityāgaḥ[Vedāntasāra, 21]

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Rousseau was an important influence on the development of this idea. See for example Osho's teachings for a popularisation of this idea.

- ↑ James also gives descriptions of conversion experiences. The Christian model of dramatic conversions, based on the role-model of Paul's conversion, may also have served as a model for Western interpretations and expectations regarding "enlightenment", similar to Protestant influences on Theravada Buddhism, as described by Carrithers: "It rests upon the notion of the primacy of religious experiences, preferably spectacular ones, as the origin and legitimation of religious action. But this presupposition has a natural home, not in Buddhism, but in Christian and especially Protestant Christian movements which prescribe a radical conversion."[45] See Sekida for an example of this influence of William James and Christian conversion stories, mentioning Luther[46] and St. Paul.[47] See also McMahan for the influence of Christian thought on Buddhism.[5]

- ↑ Robert Sharf: "[T]he role of experience in the history of Buddhism has been greatly exaggerated in contemporary scholarship. Both historical and ethnographic evidence suggests that the privileging of experience may well be traced to certain twentieth-century reform movements, notably those that urge a return to zazen or vipassana meditation, and these reforms were profoundly influenced by religious developments in the west [...] While some adepts may indeed experience "altered states" in the course of their training, critical analysis shows that such states do not constitute the reference point for the elaborate Buddhist discourse pertaining to the "path".[50]

- ↑ William Blake: "If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thru' narrow chinks of his cavern."[web 20]

- ↑ See McMahan, "The making of Buddhist modernity"[5] and Rambachan, "The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas"[18] for descriptions of this mutual exchange.

References

- ↑ Fischer-Schreiber, Ehrhard & Diener 2008, p. 5051, lemma "bodhi".

- ↑ Carrette & King 2005.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Sharf 1995b.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sharf 2000.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 McMahan 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Lucas 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Marek 2008, p. 10, note 6.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jacobs 2004, p. 82.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Davis 2010, p. 48.

- ↑ Yogani 2011, p. 805.

- ↑ Caplan 2009, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Lucas 2011, p. 102-105.

- ↑ Gleig 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Madhukar 2006, pp. 1-16, (Interview with Sri H.W.L. Poonja).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Mukerji 1983.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Comans 1993.

- ↑ Comans 2000, p. 307.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Rambachan 1994.

- ↑ Baptiste 2011.

- ↑ Yogani 2011.

- ↑ Lardner Carmody & Carmody 1996, p. 68.

- ↑ Sarbacker 2005, p. 1–2.

- ↑ Doshi 2007.

- ↑ Whicher 1998, p. 38–39.

- ↑ Larson 2008, p. 139–140.

- ↑ Birdee 2008.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Puligandla 1997, p. 251-254.

- ↑ Adi Shankara, Tattva bodha (1.2)

- ↑ Wright 2000, p. 181-183.

- ↑ Ruffin 2007, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Demieville 1991.

- ↑ Confessions IV.xv.25

- ↑ Confessions X.ii.2

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005a.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005b.

- ↑ Dumonlin 2000.

- ↑ Wilber 1996.

- ↑ Warder 2000, p. 116-124.

- ↑ Kalupahana 1992, p. xi.

- ↑ Hori 1999, p. 47.

- ↑ King 2002.

- ↑ Versluis 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Hart 1995.

- ↑ Sharf 2000, p. 271.

- ↑ Carrithers 1983, p. 18.

- ↑ Sekida 1985, p. 196-197.

- ↑ Sekida 1985, p. 251.

- ↑ Mohr 2000, p. 282-286.

- ↑ Low 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ Sharf 1995c, p. 1.

- ↑ Hori 1994, p. 30.

- ↑ Samy 1998, p. 82.

- ↑ Mohr 2000, p. 282.

- ↑ Samy 1998, p. 80-82.

- ↑ Samy 1998, p. 80.

- ↑ Mohr 2000, p. 284.

- ↑ Chafer 1993, p. 12–14.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Hanegraaff 1996.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Hood 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Ouspensky n.d.

- ↑ Katz 2007.

- ↑ Renard 2010, p. 59.

- ↑ Wolfe 2009, p. iii.

- ↑ Swartz 2010, p. 306.

- ↑ Aveling 1999.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 Yandell 1994, p. 25.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Yandell 1994.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 18.

- ↑ Berger 1990.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 19-23.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 23-31.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 24-26.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 24-25, 26-27.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 24-25.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Yandell 1994, p. 30.

- ↑ Yandell 1994, p. 29.

- ↑ Dennett 1992.

- ↑ Ramachandran 2012.

- ↑ Damasio 2012.

- ↑ Greenfield 2000.

- ↑ Hofstadter 2007.

- ↑ Rahula 1959, p. 66.

- ↑ Parfit 1987.

Sources

Published sources

- Aveling, Harry (1999), Osho Rajaneesh & His Disciples: Some Western Perceptions, Motilall Banarsidass

- Baptiste, Sherry (2011), Yoga with Weights for Dummies, ISBN 978-0-471-74937-0, https://archive.org/details/yogawithweightsf00bapt_0

- Berger, Peter L. (1990), The Sacred Canopy. Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion, New York: Anchor Books

- Birdee, Gurjeet S. (2008), Characteristics of Yoga Users: Results of a National Survey. In: Journal of General Internal Medicine. Oct 2008, Volume 23 Issue 10. p.1653-1658

- Caplan, Mariana (2009), Eyes Wide Open: Cultivating Discernment on the Spiritual Path, Sounds True

- Carrette, Jeremy; King, Richard (2005), Selling Spirituality: The Silent Takeover of Religion, Routledge, ISBN 0203494873, http://islamicblessings.com/upload/Selling-Spirituality-the-Silent-Takeover-of-Religion.pdf

- Carrithers, Michael (1983), The Forest Monks of Sri Lanka

- Chafer, Lewis Sperry (1993), Systematic Theology, 1 (Reprint ed.), Kregel Academic, ISBN 978-0-8254-2340-6

- Collinson, Diané; Wilkinson, Robert (1994), Thirty-Five Oriental Philosophers, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02596-6

- Comans, Michael (January 1993), "The Question of the Importance of Samadhi in Modern and Classical Advaita Vedanta", Philosophy East and West 43 (1): 19–38, doi:10.2307/1399467, http://www.realization.org/page/doc2/doc200.html

- Comans, Michael (2000), The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Crick, Francis (1994), The Astonishing Hypothesis, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company

- Damasio, A. (2012), Self comes to mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain, Vintage

- Davis, Leesa S. (2010), Advaita Vedānta and Zen Buddhism: Deconstructive Modes of Spiritual Inquiry, Continuum International Publishing Group

- Demieville, Paul (1991), The Mirror of the Mind. In: Peter N. Gregory (editor) (1991), Sudden and Gradual. Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Dennett, Daniel C. (1992), Consciousness Explained, Allen Lane The Penguin Press

- Dense, Christian D. Von (1999), Philosophers and Religious Leaders, Greenwood Publishing Group

- Deutsch, Eliot (1988), Advaita Vedanta: A Philosophical Reconstruction, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-88706-662-3, https://archive.org/details/experienceofhind00zell

- Doshi, Manu Doshi (2007), Translation of Tattvarthasutra, Ahmedabad: Shrut Ratnakar

- Dumonlin, Heinrich (2000), A History of Zen Buddhism, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005a), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005b), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 978-0-941532-90-7

- Fischer-Schreiber, Ingrid; Ehrhard, Franz-Karl; Diener, Michael S. (2008), Lexicon Boeddhisme. Wijsbegeerte, religie, psychologie, mystiek, cultuur en literatuur, Asoka

- Gleig, Ann Louise (2011), Enlightenment After the Enlightenment: American Transformations of Asian Contemplative Traditions, ProQuest 885589248

- Greenfield, Susan (2000), The Private Life of the Brain: Emotions, Consciousness, and the Secret of the Self, New York: John Wiley & Sons

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (1996), New Age Religion and Western Culture. Esotericism in the mirror of Secular Thought, Leiden/New York/Koln: E.J. Brill

- Hart, James D., ed. (1995), Transcendentalism. In: The Oxford Companion to American Literature, Oxford University Press

- Hofstadter, Douglas R. (2007), "I Am a Strange Loop", Physics Today (Basic Books) 60 (10): 56, doi:10.1063/1.2800100, Bibcode: 2007PhT....60j..56H

- Hood, Ralph W. (2001), Dimensions of Mystical Experiences: Empirical Studies and Psychological Links, Rodopi

- Hori, Victor Sogen (Winter 1994), "Teaching and Learning in the Zen Rinzai Monastery", Journal of Japanese Studies 20 (1): 5–35, doi:10.2307/132782, http://www.essenes.net/pdf/Teaching%20and%20Learning%20in%20the%20Rinzai%20Zen%20Monastery%20.pdf

- Hori, Victor Sogen (1999), Translating the Zen Phrase Book. In: Nanzan Bulletin 23 (1999), http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/HistoricalZen/translating_zen_phrasebook.pdf

- Indich, William M. (1995), Consciousness in Advaita Vedānta, Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-1251-4

- Jacobs, Alan (2004), Advaita and Western Neo-Advaita. In: The Mountain Path Journal, autumn 2004, pages 81-88, Ramanasramam, http://www.sriramanamaharshi.org/mpath/2004/october/mp.swf

- Kalupahana, David J. (1992), A history of Buddhist philosophy, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Kapleau, Philip (1989), The Three Pillars of Zen, ISBN 978-0-385-26093-0

- Katz, Jerry (2007), One: Essential Writings on Nonduality, Sentient Publications

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- Lardner Carmody, Denise; Carmody, John (1996), Serene Compassion, Oxford University Press US

- Larson, Gerald James (2008), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India's philosophy of meditation, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, Boston & London: Shambhala

- Lucas, Phillip Charles (2011), "When a Movement Is Not a Movement. Ramana Maharshi and Neo-Advaita in North America", Nova Religio 15 (2): 93–114, doi:10.1525/nr.2011.15.2.93

- Marek, David (2008), Dualität - Nondualität. Konzeptuelles und nichtkonzeptuelles Erkennen in Psychologie und buddhistischer Praxis, http://othes.univie.ac.at/2482/1/2008-10-31_9306082.pdf

- Madhukar (2006). The Simplest Way (2nd ed.). Editions India. ISBN 978-8-18965804-5.

- McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195183276

- Mohr, Michel (2000), Emerging from Nonduality. Koan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin. In: steven Heine & Dale S. Wright (eds.)(2000), "The Koan. texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism", Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Mukerji, Mādhava Bithika (1983), Neo-Vedanta and Modernity, Ashutosh Prakashan Sansthan, http://www.anandamayi.org/books/Bithika2.htm

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004). A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy. Part Two. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited (Reprint of orig: 1950, Shoki No Vedanta Tetsugaku, Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo).

- Newland, Terry (1988), MIND IS A MYTH - Disquieting Conversations with the Man Called U.G., Post Betim: Dinesh Publications

- Ouspensky, P.D. (n.d.), In Search of the Miraculous

- Parfit, D. (1987), Divided minds and the nature of persons. In C. Blakemore and S. Greenfield (eds.) (1987), "Mindwaves". Oxford, Blackwell. Pages 19-26

- Porter, Roy (2001), The Enlightenment (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0-333-94505-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=z6C9zlVo7cAC

- Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997), Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

- Rahula, W. (1959), What the Buddha taught, London & New York: Gordon Fraser & Grove Press.

- Ramachandran, V. S. (2012), The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human, W. W. Norton & Company

- Rambachan, Anatanand (1994), The Limits of Scripture: Vivekananda's Reinterpretation of the Vedas, University of Hawaii Press

- Renard, Philip (2010), Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg, Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip

- Ruffin, J. Rixey (2007). A Paradise of Reason: William Bentley and Enlightenment Christianity in the Early Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19532651-2.

- Samy, AMA (1998), Waarom kwam Bodhidharma naar het Westen? De ontmoeting van Zen met het Westen, Asoka: Asoka

- Sarbacker, Stuart Ray (2005), Samādhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga, SUNY Press

- Sekida, Katsuki (1985), Zen Training. Methods and Philosophy, New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995b), "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience", NUMEN 42 (3): 228–283, doi:10.1163/1568527952598549, http://buddhiststudies.berkeley.edu/people/faculty/sharf/documents/Sharf1995,%20Buddhist%20Modernism.pdf, retrieved 2012-10-28

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995c), "Sanbokyodan. Zen and the Way of the New Religions", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 22 (3–4), doi:10.18874/jjrs.22.3-4.1995.417-458, http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/CriticalZen/sanbokyodan%20zen.pdf

- Sharf, Robert H. (2000), "The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion", Journal of Consciousness Studies 7 (11–12): 267–87, http://buddhiststudies.berkeley.edu/people/faculty/sharf/documents/Sharf1998,%20Religious%20Experience.pdf, retrieved 2012-10-28

- Swartz, James (2010), How to Attain Enlightenment: The Vision of Non-Duality, Sentient Publications

- Versluis, Arthur (2001), The Esoteric Origins of the American Renaissance, Oxford University Press

- Warder, A.K. (2000), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

- Whicher, Ian (1998), The Integrity of the Yoga Darśana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3815-2

- Wilber, Ken (1996), The Atman Project

- Wolfe, Robert (2009), Living Nonduality: Enlightenment Teachings of Self-Realization, Karina Library

- Wright, Dale S. (2000), Philosophical Meditations on Zen Buddhism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Yandell, Keith E. (1994), The Epistemology of Religious Experience, Cambridge University Press

- Yogani (2011), Advanced Yoga Practices – Easy Lessons for Ecstatic Living, ISBN 978-0-9819255-2-3

- Zelliot, Eleanor; Berntsen, Maxine (1980), The Experience of Hinduism: essays on religion in Maharashtra, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-8248-0271-3

Web-sources

- ↑ Lauri Glenn (2018). "What is bodhi?". Bodhi Therapeutics. https://www.lauriglenn.com/bodhi/.

- ↑ Timothy Conway, Neo-Advaita or Pseudo-Advaita and Real Advaita-Nonduality

- ↑ James Swartz, What is Neo-Advaita?

- ↑ What is Enlightenment? September 1, 2006

- ↑ What is Enlightenment? December 31, 2001

- ↑ What is Enlightenment? December 1, 2005

- ↑ "The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 2/Jnana-Yoga/The Absolute and Manifestation - Wikisource". En.wikisource.org. 2008-04-05. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Complete_Works_of_Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_2/Jnana-Yoga/The_Absolute_and_Manifestation.

- ↑ Shankara, Adi. "The Crest Jewel of Wisdom". pp. Ch. 1. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/cjw/cjw05.htm.

- ↑ "Advaita Yoga Ashrama, Jnana Yoga. Introduction". Yoga108.org. http://yoga108.org/pages/show/55.

- ↑ "Antahkarana- Yoga (definition)". En.mimi.hu. http://en.mimi.hu/yoga/antahkarana.html.

- ↑ Sri Swami Sivananda, Karma Yoga

- ↑ Bernard Faure, Chan/Zen Studies in English: The State Of The Field

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Illumination and Enlightenment

- ↑ Robert H. Sharf, Whose Zen? Zen Nationalism Revisited

- ↑ Hu Shih: Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism in China. Its History and Method

- ↑ Critical introduction by John McRae to the reprint of Dumoulin's A history of Zen

- ↑ Nanzan Institute: Pruning the bodhi Tree

- ↑ David Chapman: Effing the ineffable

- ↑ Quote DB

- ↑ Contemplative Outreach: Centering Prayer

- ↑ Inner Explorations: Christian Enlightenment?

- ↑ "Undivided Journal, About the Journal". http://undividedjournal.com/about-the-journal/.

External links

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Epistemology (philosophy)

- Bruce Hood (2012), What is the Self Illusion? An interview with Sam Harris