Social:Bengali language

| Bengali | |

|---|---|

| Bangla | |

| বাংলা | |

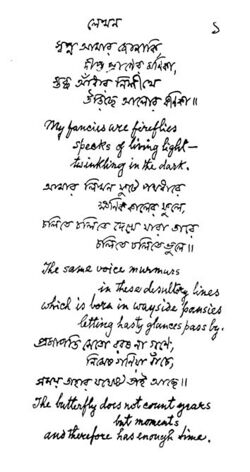

The word "Bangla" in Bengali script | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈbaŋla] ( |

| Native to | Bangladesh and India |

| Region | Bangladesh India

|

| Ethnicity | Bengalis |

Native speakers | L1: 234 million (2011–2021)[1][2] L2: 39 million (2011–2017)[1] Total: 270 million[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Magadhi Prakrit

|

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Bengali Sign Language (BdSL)[3] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Bangla Academy (Bangladesh) Pashchimbanga Bangla Akademi (West Bengal) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | bn |

| ISO 639-1 | ben |

| ISO 639-3 | ben |

| Glottolog | beng1280[5] |

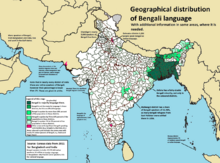

Map of Bengali language in Bangladesh and India (district-wise). Darker shades imply a greater percentage of native speakers of Bengali in each district. | |

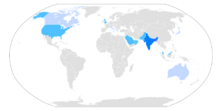

Bengali-speaking diaspora Worldwide. | |

Bengali,[lower-alpha 1] generally known by its endonym Bangla (বাংলা [ˈbaŋla] (![]() listen)), is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Bengal region of South Asia. With approximately 234 million native speakers and another 39 million as second language speakers as of 2017,[1] Bengali is the sixth most spoken native language and the seventh most spoken language by the total number of speakers in the world.[8][9] Bengali is the fifth most spoken Indo-European language.

listen)), is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Bengal region of South Asia. With approximately 234 million native speakers and another 39 million as second language speakers as of 2017,[1] Bengali is the sixth most spoken native language and the seventh most spoken language by the total number of speakers in the world.[8][9] Bengali is the fifth most spoken Indo-European language.

Bengali is the official, national, and most widely spoken language of Bangladesh,[10][11][12] with 98% of Bangladeshis using Bengali as their first language.[13][14] It is the second-most widely spoken language in India. It is the official language of the Indian states of West Bengal and Tripura and the Barak Valley region of the state of Assam. It is also the second official language of the Indian state of Jharkhand since September 2011.[4] It is the most widely spoken language in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal,[15] and is spoken by significant populations in other states including Bihar, Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Chhattisgarh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Odisha and Uttarakhand.[16] Bengali is also spoken by the Bengali diasporas (Bangladeshi diaspora and Indian Bengalis) in Europe, the United States, the Middle East and other countries.[17]

Bengali is the fourth fastest growing language in India, following Hindi in the first place, Kashmiri in the second place, and Meitei (Manipuri), along with Gujarati, in the third place, according to the 2011 census of India.[18]

The noted linguistic, Professor Muhammad Abdul Hye, once famously remarked that Bengali was the "French language of the East". He was referring to not only the sweetness of the language, but also the profound use of connotation, pronunciation and the subtlety of the language. [19] In fact, despite being poles apart in terms of grammar, Bengali and French are very similar in phonology. The consonant clusters are merged in a similar way to produce a simpler sound rather than a complex sound cluster. Both the languages have several pronunciation rules consonant clusters.

Bengali has developed over more than 1,300 years. Bengali literature, with its millennium-old literary history, was extensively developed during the Bengali Renaissance and is one of the most prolific and diverse literary traditions in Asia. The Bengali language movement from 1948 to 1956 demanding that Bengali be an official language of Pakistan fostered Bengali nationalism in East Bengal leading to the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971. In 1999, UNESCO recognised 21 February as International Mother Language Day in recognition of the language movement.[20][21]

History

Ancient

Although Sanskrit has been spoken by Hindu Brahmins in Bengal since the 3rd century BC,[23] the local Buddhist population spoke varieties of the Prakrit.[24] These varieties are generally referred to as "eastern Magadhi Prakrit", as coined by linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji,[25] as the Middle Indo-Aryan dialects were influential in the first millennium when Bengal was a part of the Greater Magadhan realm.

The local varieties had no official status during the Gupta Empire, and with Bengal increasingly becoming a hub of Sanskrit literature for Hindu priests, the vernacular of Bengal gained a lot of influence from Sanskrit.[26] Magadhi Prakrit was also spoken in modern-day Bihar and Assam, and this vernacular eventually evolved into Ardha Magadhi.[27][28] Ardha Magadhi began to give way to what is known as Apabhraṃśa, by the end of the first millennium. The Bengali language evolved as a distinct language over the course of time.[29]

Early

Though some archaeologists claim that some 10th-century texts were in Bengali, it is not certain whether they represent a differentiated language or whether they represent a stage when Eastern Indo-Aryan languages were differentiating.[30] The local Apabhraṃśa of the eastern subcontinent, Purbi Apabhraṃśa or Abahatta (lit. 'meaningless sounds'), eventually evolved into regional dialects, which in turn formed three groups, the Bengali–Assamese languages, the Bihari languages, and the Odia language. The language was not static: different varieties coexisted and authors often wrote in multiple dialects in this period. For example, Ardhamagadhi is believed to have evolved into Abahatta around the 6th century, which competed with the ancestor of Bengali for some time.[31][better source needed] The ancestor of Bengali was the language of the Pala Empire and the Sena dynasty.[32][33]

Medieval

During the medieval period, Middle Bengali was characterised by the elision of the word-final অ ô and the spread of compound verbs, which originated from the Sanskrit Schwa. Slowly, the word-final ô disappeared from many words influenced by the Arabic, Persian, and Turkic languages. The arrival of merchants and traders from the Middle East and Turkestan into the Buddhist-ruling Pala Empire, from as early as the 7th century, gave birth to Islamic influence in the region.[citation needed] In the 13th century, the subsequent Muslim expeditions to Bengal greatly encouraged the migratory movements of Arab Muslims and Turco-Persians, who heavily influenced the local vernacular by settling among the native population.[citation needed]

Bengali acquired prominence, over Persian, in the court of the Sultans of Bengal with the ascent of Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah.[34] Subsequent Muslim rulers actively promoted the literary development of Bengali,[35] allowing it to become the most spoken vernacular language in the Sultanate.[36] Bengali adopted many words from Arabic and Persian, which was a manifestation of Islamic culture on the language. Major texts of Middle Bengali (1400–1800) include Yusuf-Zulekha by Shah Muhammad Sagir and Srikrishna Kirtana by the Chandidas poets. Court support for Bengali culture and language waned when the Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the late 16th and early 17th century.[37]

Modern

The modern literary form of Bengali was developed during the 19th and early 20th centuries based on the west-central dialect spoken in the Nadia region. Bengali shows a high degree of diglossia, with the literary and standard form differing greatly from the colloquial speech of the regions that identify with the language.[38] Modern Bengali vocabulary is based on words inherited from Magadhi Prakrit and Pali, along with tatsamas and reborrowings from Sanskrit and borrowings from Persian, Arabic, Austroasiatic languages and other languages with which it has historically been in contact.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, there were two main forms of written Bengali:

- চলিতভাষা Chôlitôbhasha, a colloquial form of Bengali using simplified inflections.

- সাধুভাষা Sadhubhasha, a Sanskritised form of Bengali.[39]

In 1948, the Government of Pakistan tried to impose Urdu as the sole state language in Pakistan, giving rise to the Bengali language movement.[40] This was a popular ethnolinguistic movement in the former East Bengal (today Bangladesh), which arose as a result of the strong linguistic consciousness of the Bengalis and their desire to promote and protect spoken and written Bengali's recognition as a state language of the then Dominion of Pakistan. On 21 February 1952, five students and political activists were killed during protests near the campus of the University of Dhaka; they were the first ever martyrs to die for their right to speak their mother tongue. In 1956, Bengali was made a state language of Pakistan.[40] 21 February has since been observed as Language Movement Day in Bangladesh and has also been commemorated as International Mother Language Day by UNESCO every year since 2000.

In 2010, the parliament of Bangladesh and the legislative assembly of West Bengal proposed that Bengali be made an official United Nations language.[41] As of January 2023, no further action has been yet taken on this matter. However, in 2022, the UN did adopt Bangla as an unofficial language, after a resolution tabled by India.[42]

Geographical distribution

Approximate distribution of native Bengali speakers (assuming a rounded total of 261 million) worldwide.

The Bengali language is native to the region of Bengal, which comprises the present-day nation of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

Besides the native region it is also spoken by the Bengalis living in Tripura, southern Assam and the Bengali population in the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Bengali is also spoken in the neighbouring states of Odisha, Bihar, and Jharkhand, and sizeable minorities of Bengali speakers reside in Indian cities outside Bengal, including Delhi, Mumbai , Thane, Varanasi, and Vrindavan. There are also significant Bengali-speaking communities in the Middle East,[43][44][45] the United States,[46] Singapore,[47] Malaysia, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

Official status

The 3rd article of the Constitution of Bangladesh states Bengali to be the sole official language of Bangladesh.[12] The Bengali Language Implementation Act, 1987, made it mandatory to use Bengali in all records and correspondences, laws, proceedings of court and other legal actions in all courts, government or semi-government offices, and autonomous institutions in Bangladesh.[10] It is also the de facto national language of the country.

In India, Bengali is one of the 23 official languages.[48] It is the official language of the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and in Barak Valley of Assam.[49][50] Bengali has been a second official language of the Indian state of Jharkhand since September 2011.

In Pakistan , Bengali is a recognised secondary language in the city of Karachi.[51][52][53] The Department of Bengali in the University of Karachi also offers regular programs of studies at the Bachelors and at the Masters levels for Bengali Literature.[54]

The national anthems of both Bangladesh (Amar Sonar Bangla) and India (Jana Gana Mana) were written in Bengali by the Bengali Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[55] Additionally, the first two verses of Vande Mataram, a patriotic song written in Bengali by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, was adopted as the "national song" of India in both the colonial period and later in 1950 in independent India. Furthermore, it is believed by many that the national anthem of Sri Lanka (Sri Lanka Matha) was inspired by a Bengali poem written by Rabindranath Tagore,[56][57][58][59] while some even believe the anthem was originally written in Bengali and then translated into Sinhala.[60][61][62][63]

After the contribution made by the Bangladesh UN Peacekeeping Force in the Sierra Leone Civil War under the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone, the government of Ahmad Tejan Kabbah declared Bengali as an honorary official language in December 2002.[64][65][66][67]

In 2009, elected representatives in both Bangladesh and West Bengal called for Bengali to be made an official language of the United Nations.[68]

Dialects

Regional varieties in spoken Bengali constitute a dialect continuum. Linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji grouped the dialects of Bengali language into four large clusters- Rarhi, Vangiya, Kamrupi and Varendri;[69][70] but many alternative grouping schemes have also been proposed.[71] The south-western dialects (Rarhi or Nadia dialect) form the basis of modern standard colloquial Bengali. In the dialects prevalent in much of eastern and south-eastern Bangladesh (Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka and Sylhet Divisions of Bangladesh), many of the stops and affricates heard in West Bengal and western Bangladesh are pronounced as fricatives. Western alveolo-palatal affricates চ [tɕɔ], ছ [tɕʰɔ], জ [dʑɔ] correspond to eastern চ [tsɔ], ছ [tsʰɔ~sɔ], জ [dzɔ~zɔ]. The influence of Tibeto-Burman languages on the phonology of Eastern Bengali is seen through the lack of nasalised vowels and an alveolar articulation of what are categorised as the "cerebral" consonants (as opposed to the postalveolar articulation of western Bengal). Some variants of Bengali, particularly Chittagonian and Chakma, have contrastive tone; differences in the pitch of the speaker's voice can distinguish words. Kharia Thar and Mal Paharia are closely related to Western Bengali dialects, but are typically classified as separate languages. Similarly, Hajong is considered a separate language, although it shares similarities to Northern Bengali dialects.[72]

During the standardisation of Bengali in the 19th century and early 20th century, the cultural centre of Bengal was in Kolkata, a city founded by the British. What is accepted as the standard form today in both West Bengal and Bangladesh is based on the West-Central dialect of Nadia and Kushtia District.[73] There are cases where speakers of Standard Bengali in West Bengal will use a different word from a speaker of Standard Bengali in Bangladesh, even though both words are of native Bengali descent. For example, the word salt is লবণ lôbôṇ in the east which corresponds to নুন nun in the west.[74]

Bengali exhibits diglossia, though some scholars have proposed triglossia or even n-glossia or heteroglossia between the written and spoken forms of the language.[38] Two styles of writing have emerged, involving somewhat different vocabularies and syntax:[73][75]

- Shadhu-bhasha (সাধু ভাষা "upright language") was the written language, with longer verb inflections and more of a Pali and Sanskrit-derived Tatsama vocabulary. Songs such as India's national anthem Jana Gana Mana (by Rabindranath Tagore) were composed in this style. Its use in modern writing however is uncommon, restricted to some official signs and documents in Bangladesh as well as for achieving particular literary effects.

- Cholito-bhasha (চলিত ভাষা "running language"), known by linguists as Standard Colloquial Bengali, is a written Bengali style exhibiting a preponderance of colloquial idiom and shortened verb forms and is the standard for written Bengali now. This form came into vogue towards the turn of the 19th century, promoted by the writings of Peary Chand Mitra (Alaler Gharer Dulal, 1857),[76] Pramatha Chaudhuri (Sabujpatra, 1914) and in the later writings of Rabindranath Tagore. It is modelled on the dialect spoken in the Shantipur and Shilaidaha region in Nadia and Kushtia Districts. This form of Bengali is often referred to as the "Kushtia standard"(Bangladesh), "Nadia dialect" (West Bengal), "Southwestern/West-Central dialect" "Shantipuri Bangla" or "Shilaidahi Bangla".[71]

Linguist Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar categorises the language as:

- Madhya Rarhi dialect

- Kanthi (Contai) dialect

- Kolkata dialect

- Shantipuriya (Nadia) dialect

- Shershahabadia (Maldahiya/ Jangipuri) dialect

- Barendri dialect

- Rangapuriya dialect

- Sylheti dialect

- Dhakiya (Bikrampuri) dialect

- Jashore/Jessoriya dialect

- Barisal (Chandradwip) dialect

- Chattal (Chittagong) dialect

While most writing is in Standard Colloquial Bengali (SCB), spoken dialects exhibit a greater variety. People in southeastern West Bengal, including Kolkata, speak in SCB. Other dialects, with minor variations from Standard Colloquial, are used in other parts of West Bengal and western Bangladesh, such as the Midnapore dialect, characterised by some unique words and constructions. However, a majority in Bangladesh speaks dialects notably different from SCB. Some dialects, particularly those of the Chittagong region, bear only a superficial resemblance to SCB.[77] The dialect in the Chittagong region is least widely understood by the general body of Bengalis.[77] The majority of Bengalis are able to communicate in more than one variety – often, speakers are fluent in Cholitobhasha (SCB) and one or more regional dialects.[39]

Even in SCB, the vocabulary may differ according to the speaker's religion: Muslims are more likely to use words of Persian and Arabic origin, along with more words naturally derived from Sanskrit (tadbhava), whereas Hindus are more likely to use tatsama (words directly borrowed from Sanskrit).[78] For example:[74]

| Predominantly Hindu usage | Origin | Predominantly Muslim usage | Origin | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| নমস্কার nômôskār | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit namaskāra | আসসালামু আলাইকুম āssālāmu ālāikum | Directly from Arabic as-salāmu ʿalaykum | hello |

| নিমন্ত্রণ nimôntrôṇ | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit nimantraṇa as opposed to the native Bengali nemôntônnô | দাওয়াত dāowāt | Borrowed from Arabic da`wah via Persian | invitation |

| জল jôl | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit jala | পানি pāni | Native, compare with Sanskrit pānīya | water |

| স্নান snān | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit snāna | গোসল gosôl | Borrowed from Arabic ghusl via Persian | bath |

| দিদি didi | Native, from Sanskrit devī | আপা āpā | From Turkic languages | sister / elder sister |

| দাদা dādā | Native, from Sanskrit dāyāda | ভাইয়া bhāiyā | Native, from Sanskrit bhrātā | brother / elder brother[79] |

| মাসী māsī | Native, from Sanskrit mātṛṣvasā | খালা khālā | Directly borrowed from Arabic khālah | maternal aunt |

| পিসী pisī | Native, from Sanskrit pitṛṣvasā | ফুফু phuphu | Native, from Prakrit phupphī | paternal aunt |

| কাকা kākā | From Persian or Dravidian kākā | চাচা chāchā | From Prakrit cācca | paternal uncle |

| প্রার্থনা prārthonā | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit prārthanā | দোয়া doyā | Borrowed from Arabic du`āʾ | prayer |

| প্রদীপ prôdīp | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit pradīp | বাতি bāti | Native, compare with Prakrit batti and Sanskrit barti | lamp |

| লঙ্কা lônkā | Native, named after Lanka | মরিচ môrich | Directly borrowed from Sanskrit marica | chilli |

Phonology

The phonemic inventory of standard Bengali consists of 29 consonants and 7 vowels, as well as 7 nasalised vowels. The inventory is set out below in the International Phonetic Alphabet (upper grapheme in each box) and romanisation (lower grapheme).

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ই~ঈ i i |

উ~ঊ u u | |

| Close-mid | এ e e |

ও o o | |

| Open-mid | অ্যা æ æ |

অ ɔ ô | |

| Open | আ a a |

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ইঁ~ঈঁ ĩ ĩ |

উঁ~ঊঁ ũ ũ | |

| Close-mid | এঁ ẽ ẽ |

ওঁ õ õ | |

| Open-mid | এ্যাঁ / অ্যাঁ æ̃ æ̃ |

অঁ ɔ̃ ɔ̃ | |

| Open | আঁ ã ã |

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palato- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | unaspirated | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | unaspirated | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | (ɸ) | s | ʃ | (h) | |||

| voiced | (β) | (z) | ɦ | |||||

| Approximant | (w) | l | (j) | |||||

| Rhotic | unaspirated | r | ɽ | |||||

| aspirated | (ɽʱ) | |||||||

Bengali is known for its wide variety of diphthongs, combinations of vowels occurring within the same syllable.[80] Two of these, /oi̯/ and /ou̯/, are the only ones with representation in script, as ঐ and ঔ respectively. /e̯ i̯ o̯ u̯/ may all form the glide part of a diphthong. The total number of diphthongs is not established, with bounds at 17 and 31. An incomplete chart is given by Sarkar (1985) of the following:[81]

| e̯ | i̯ | o̯ | u̯ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ae̯ | ai̯ | ao̯ | au̯ |

| æ | æe̯ | æo̯ | ||

| e | ei̯ | eu̯ | ||

| i | ii̯ | iu̯ | ||

| o | oe̯ | oi̯ | oo̯ | ou̯ |

| u | ui̯ |

Stress

In standard Bengali, stress is predominantly initial. Bengali words are virtually all trochaic; the primary stress falls on the initial syllable of the word, while secondary stress often falls on all odd-numbered syllables thereafter, giving strings such as in সহযোগিতা shô-hô-jo-gi-ta "cooperation", where the boldface represents primary and secondary stress.

Consonant clusters

Native Bengali words do not allow initial consonant clusters;[82] the maximum syllabic structure is CVC (i.e., one vowel flanked by a consonant on each side). Many speakers of Bengali restrict their phonology to this pattern, even when using Sanskrit or English borrowings, such as গেরাম geram (CV.CVC) for গ্রাম gram (CCVC) "village" or ইস্কুল iskul (VC.CVC) for স্কুল skul (CCVC) "school".

Writing system

The Bengali-Assamese script is an abugida, a script with letters for consonants, with diacritics for vowels, and in which an inherent vowel (অ ô) is assumed for consonants if no vowel is marked.[83] The Bengali alphabet is used throughout Bangladesh and eastern India (Assam, West Bengal, Tripura). The Bengali alphabet is believed to have evolved from a modified Brahmic script around 1000 CE (or 10th–11th century).[84] It is a cursive script with eleven graphemes or signs denoting nine vowels and two diphthongs, and thirty-nine graphemes representing consonants and other modifiers.[84] There are no distinct upper and lower case letter forms. The letters run from left to right and spaces are used to separate orthographic words. Bengali script has a distinctive horizontal line running along the tops of the graphemes that links them together called মাত্রা matra.[85]

Since the Bengali script is an abugida, its consonant graphemes usually do not represent phonetic segments, but carry an "inherent" vowel and thus are syllabic in nature. The inherent vowel is usually a back vowel, either [ɔ] as in মত [mɔt] "opinion" or [o], as in মন [mon] "mind", with variants like the more open [ɒ]. To emphatically represent a consonant sound without any inherent vowel attached to it, a special diacritic, called the hôsôntô (্), may be added below the basic consonant grapheme (as in ম্ [m]). This diacritic, however, is not common and is chiefly employed as a guide to pronunciation. The abugida nature of Bengali consonant graphemes is not consistent, however. Often, syllable-final consonant graphemes, though not marked by a hôsôntô, may carry no inherent vowel sound (as in the final ন in মন [mon] or the medial ম in গামলা [ɡamla]).

A consonant sound followed by some vowel sound other than the inherent [ɔ] is orthographically realised by using a variety of vowel allographs above, below, before, after, or around the consonant sign, thus forming the ubiquitous consonant-vowel typographic ligatures. These allographs, called কার kar, are diacritical vowel forms and cannot stand on their own. For example, the graph মি [mi] represents the consonant [m] followed by the vowel [i], where [i] is represented as the diacritical allograph ি (called ই-কার i-kar) and is placed before the default consonant sign. Similarly, the graphs মা [ma], মী [mi], মু [mu], মূ [mu], মৃ [mri], মে [me~mɛ], মৈ [moj], মো [mo] and মৌ [mow] represent the same consonant ম combined with seven other vowels and two diphthongs. In these consonant-vowel ligatures, the so-called "inherent" vowel [ɔ] is first expunged from the consonant before adding the vowel, but this intermediate expulsion of the inherent vowel is not indicated in any visual manner on the basic consonant sign ম [mɔ].

The vowel graphemes in Bengali can take two forms: the independent form found in the basic inventory of the script and the dependent, abridged, allograph form (as discussed above). To represent a vowel in isolation from any preceding or following consonant, the independent form of the vowel is used. For example, in মই [moj] "ladder" and in ইলিশ [iliʃ] "Hilsa fish", the independent form of the vowel ই is used (cf. the dependent formি). A vowel at the beginning of a word is always realised using its independent form.

In addition to the inherent-vowel-suppressing hôsôntô, three more diacritics are commonly used in Bengali. These are the superposed chôndrôbindu (ঁ), denoting a suprasegmental for nasalisation of vowels (as in চাঁদ [tʃãd] "moon"), the postposed ônusbar (ং) indicating the velar nasal [ŋ] (as in বাংলা [baŋla] "Bengali") and the postposed bisôrgô (ঃ) indicating the voiceless glottal fricative [h] (as in উঃ! [uh] "ouch!") or the gemination of the following consonant (as in দুঃখ [dukʰːɔ] "sorrow").

The Bengali consonant clusters (যুক্তব্যঞ্জন juktôbênjôn) are usually realised as ligatures, where the consonant which comes first is put on top of or to the left of the one that immediately follows. In these ligatures, the shapes of the constituent consonant signs are often contracted and sometimes even distorted beyond recognition. In the Bengali writing system, there are nearly 285 such ligatures denoting consonant clusters. Although there exist a few visual formulas to construct some of these ligatures, many of them have to be learned by rote. Recently, in a bid to lessen this burden on young learners, efforts have been made by educational institutions in the two main Bengali-speaking regions (West Bengal and Bangladesh) to address the opaque nature of many consonant clusters, and as a result, modern Bengali textbooks are beginning to contain more and more "transparent" graphical forms of consonant clusters, in which the constituent consonants of a cluster are readily apparent from the graphical form. However, since this change is not as widespread and is not being followed as uniformly in the rest of the Bengali printed literature, today's Bengali-learning children will possibly have to learn to recognise both the new "transparent" and the old "opaque" forms, which ultimately amounts to an increase in learning burden.

Bengali punctuation marks, apart from the downstroke । daṛi – the Bengali equivalent of a full stop – have been adopted from Western scripts and their usage is similar.[86]

Unlike in Western scripts (Latin, Cyrillic, etc.) where the letter forms stand on an invisible baseline, the Bengali letter-forms instead hang from a visible horizontal left-to-right headstroke called মাত্রা matra. The presence and absence of this matra can be important. For example, the letter ত tô and the numeral ৩ "3" are distinguishable only by the presence or absence of the matra, as is the case between the consonant cluster ত্র trô and the independent vowel এ e, also the letter হ hô and Bengali Ôbogroho ঽ (~ô) and letter ও o and consonant cluster ত্ত ttô. The letter-forms also employ the concepts of letter-width and letter-height (the vertical space between the visible matra and an invisible baseline).

There is yet to be a uniform standard collating sequence (sorting order of graphemes to be used in dictionaries, indices, computer sorting programs, etc.) of Bengali graphemes. Experts in both Bangladesh and India are currently working towards a common solution for this problem.

Alternative and historic scripts

Throughout history, there have been instances of the Bengali language being written in different scripts, though these employments were never popular on a large scale and were communally limited. Owing to Bengal's geographic location, Bengali areas bordering non-Bengali regions have been influenced by each other. Small numbers of people in Midnapore, which borders Odisha, have used the Odia script to write in Bengali. In the border areas between West Bengal and Bihar, some Bengali communities historically wrote Bengali in Devanagari, Kaithi and Tirhuta.[87]

In Sylhet and Bankura, modified versions of the Kaithi script had some historical prominence, mainly among Muslim communities. The variant in Sylhet was identical to the Baitali Kaithi script of Hindustani with the exception of Sylhet Nagri possessing matra.[88] Sylhet Nagri was standardised for printing in c. 1869.[11]

Up until the 19th century, numerous variations of the Arabic script had been used across Bengal from Chittagong in the east to Meherpur in the west.[89][90][91] The 14th-century court scholar of Bengal, Nur Qutb Alam, composed Bengali poetry using the Persian alphabet.[92][93] After the Partition of India in the 20th century, the Pakistani government attempted to institute the Perso-Arabic script as the standard for Bengali in East Pakistan; this was met with resistance and contributed to the Bengali language movement.[94]

In the 16th century, Portuguese missionaries began a tradition of using the Roman alphabet to transcribe the Bengali language. Though the Portuguese standard did not receive much growth, a few Roman Bengali works relating to Christianity and Bengali grammar were printed as far as Lisbon in 1743. The Portuguese were followed by the English and French respectively, whose works were mostly related to Bengali grammar and transliteration. The first version of the Aesop's Fables in Bengali was printed using Roman letters based on English phonology by the Scottish linguist John Gilchrist. Consecutive attempts to establish a Roman Bengali have continued across every century since these times, and have been supported by the likes of Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Muhammad Qudrat-i-Khuda, and Muhammad Enamul Haq.[95] The Digital Revolution has also played a part in the adoption of the English alphabet to write Bengali,[96] with certain social media influencers publishing entire novels in Roman Bengali.[97]

Bengali script like others does have Schwa deletion. It does not mark when the inherent vowel is not used (mainly at the end of words)

Orthographic depth

The Bengali script in general has a comparatively shallow orthography when compared to the Latin script used for English and French, i.e., in many cases there is a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds (phonemes) and the letters (graphemes) of Bengali. But grapheme-phoneme inconsistencies do occur in many other cases. In fact, Bengali-Assamese script has the deepest orthography (deep orthography) among the Indian scripts. In general, the Bengali-Assamese script is fairly transparent for grapheme-to-phoneme conversion, i.e., it is easier to predict the pronunciation from spelling of the words. But the script is fairly opaque for phoneme-to-grapheme conversion, i.e., it is more difficult to predict the spelling from the pronunciation of the words.

One kind of inconsistency is due to the presence of several letters in the script for the same sound. In spite of some modifications in the 19th century, the Bengali spelling system continues to be based on the one used for Sanskrit,[86] and thus does not take into account some sound mergers that have occurred in the spoken language. For example, there are three letters (শ, ষ, and স) for the voiceless postalveolar fricative [ʃ], although the letter স retains the voiceless alveolar sibilant [s] sound when used in certain consonant conjuncts as in স্খলন [skʰɔlon] "fall", স্পন্দন [spɔndon] "beat", etc. The letter ষ also, sometimes, retains the voiceless retroflex sibilant [ʂ] sound when used in certain consonant conjuncts as in কষ্ট [kɔʂʈo] "suffering", গোষ্ঠী [ɡoʂʈʰi] "clan", etc. Similarly, there are two letters (জ and য) for the voiced postalveolar affricate [dʒ]. Moreover, what was once pronounced and written as a retroflex nasal ণ [ɳ] is now pronounced as an alveolar [n] when in conversation (the difference is heard when reading) (unless conjoined with another retroflex consonant such as ট, ঠ, ড and ঢ), although the spelling does not reflect this change. The near-open front unrounded vowel [æ] is orthographically realised by multiple means, as seen in the following examples: এত [æto] "so much", এ্যাকাডেমী [ækademi] "academy", অ্যামিবা [æmiba] "amoeba", দেখা [dækʰa] "to see", ব্যস্ত [bæsto] "busy", ব্যাকরণ [bækorɔn] "grammar".

Another kind of inconsistency is concerned with the incomplete coverage of phonological information in the script. The inherent vowel attached to every consonant can be either [ɔ] or [o] depending on vowel harmony (স্বরসঙ্গতি) with the preceding or following vowel or on the context, but this phonological information is not captured by the script, creating ambiguity for the reader. Furthermore, the inherent vowel is often not pronounced at the end of a syllable, as in কম [kɔm] "less", but this omission is not generally reflected in the script, making it difficult for the new reader.

Many consonant clusters have different sounds than their constituent consonants. For example, the combination of the consonants ক্ [k] and ষ [ʂ] is graphically realised as ক্ষ and is pronounced [kkʰo] (as in রুক্ষ [rukkʰo] "coarse"), [kʰɔ] (as in ক্ষমতা [kʰɔmota] "capability") or even [kʰo] (as in ক্ষতি [kʰoti] "harm"), depending on the position of the cluster in a word. Another example is that there are around 7 or more graphemes to represent the sound [ʃ]. These are 'শ' as in শব্দ ("shabda", pronounced as "shôbdo")(meaning"word"), 'ষ' as in ষড়যন্ত্র ("şaḍjantra", pronounced as "shôḍojontro")(meaning "conspiracy"), 'স' as in সরকার ("sarkāra", pronounced as "shôrkār")(meaning "government"), 'শ্ব' as in শ্বশুর (written as "shbashura" but pronounced with the ব 'b' silent, i.e., as "shoshur")( meaning "father in law"), 'শ্ম' as in শ্মশান (written as "shmashāna" but pronounced with the ম 'm' silent, i.e., as "shôshān")( meaning "crematorium"), 'স্ব' as in স্বপ্ন (written as "sbapna" but pronounced with the ব 'b' silent, i.e., as "shôpno")( meaning "dream"), 'স্ম' as in স্মরণ (written as "smaraṅa" but pronounced with the ম 'm' silent, i.e., as "shôron")( meaning "remember"), 'ষ্ম' as in গ্রীষ্ম (written as "grīşma" but pronounced with the ম 'm' silent, i.e., as "grīshsho")( meaning "summer") and so on. In most of the consonant clusters, only the first consonant is pronounced and rest of the consonants are silent. Examples are লক্ষ্মণ (written as "lakşmaṅa" but pronounced as "lôkkhon")(Lord Rama's brother in the Hindu epic Ramayana), বিশ্বাস (written as "bishbāsa" but pronounced as "bishshāsh")( belief ), বাধ্য (written as "bādhja" but pronounced as "bāddho")( bound ( to do something) )and স্বাস্থ্য (written as "sbāsthja" but pronounced as "shāstho") (health). Some consonant clusters have completely different pronunciation as compared to the constituent consonants. For example, 'হ্য' as in ঐতিহ্য where 'hy' is pronounced as 'jjh' (written as "aitihya" but pronounced as "oitijjho")(tradition). The same হ্য is pronounced as 'hæ' as in হ্যাঁ (written as "hjāṅ" but pronounced as nasalised "hæ").

Another example of inconsistency in the script is that of words like, অন্য (written as "anja" but pronounced as "onno")(other/different) and অন্ন (written as "ann'a" but pronounced as "ônno")(food grain); in these words, the letter অ is combining with two different consonant clusters ন্য ("nja") and ন্ন ("nna"), and while the same letter অ has two different pronunciations, o and ô, the two different consonant clusters have the same pronounciation, "nno". Thus, same letters and graphemes can often have different pronounciations depending on their position in a word and different graphemes and letters often have the same pronounciation.

The main reason for these numerous inconsistencies is that there have been lots of sound mergers in Bengali, but the script has failed to account for the sound shifts and consonant mergers in the language. Bengali has lots of tatsam words (words directly derived from Sanskrit) and in all these words, the original spelling has been preserved but the pronunciations have changed due to consonant mergers and sound shifts. In fact, most of the tatsam words have a lot of grapheme-to-phoneme inconsistencies while most of the tadbhav words (native Bengali words) have fairly consistent grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence. The Bengali writing system is, therefore, not often a true guide to pronunciation.

Uses

The script used for Bengali, Assamese, and other languages is known as Bengali script. The script is known as the Bengali alphabet for Bengali and its dialects and the Assamese alphabet for Assamese language with some minor variations. Other related languages in the nearby region also make use of the Bengali script like the Meitei language in the Indian state of Manipur, where the Meitei language has been written in the Bengali script for centuries, though the Meitei script has been promoted in recent times.

Number system

Bengali digits are as follows.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

There are additional digits for fractions and prices, though they are little used any longer.[vague]

Romanisation

There are various romanisation systems used for Bengali created in recent years which have failed to represent the true Bengali phonetic sound. The Bengali alphabet has often been included with the group of Brahmic scripts for romanisation where the true phonetic value of Bengali is never represented. Some of them are the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, or IAST system (based on diacritics);[98] "Indian languages Transliteration", or ITRANS (uses upper case letters suited for ASCII keyboards);[99] and the National Library at Kolkata romanisation.[100]

In the context of Bengali romanisation, it is important to distinguish transliteration from transcription. Transliteration is orthographically accurate (i.e. the original spelling can be recovered), whereas transcription is phonetically accurate (the pronunciation can be reproduced). As the spelling often doesn't reflect the actual pronunciation, transliteration and transcription are often different.

Although it might be desirable to use a transliteration scheme where the original Bengali orthography is recoverable from the Latin text, Bengali words are currently romanised on Wikipedia using a phonemic transcription, where the true phonetic pronunciation of Bengali is represented with no reference to how it is written.

The most recent attempt has been by publishers Mitra and Ghosh with the launch of three popular children's books, Abol Tabol, Hasi Khusi and Sahoj Path, in Roman script at the Kolkata Book Fair 2018. Published under the imprint of Benglish Books, these are based on phonetic transliteration and closely follow spellings used in social media but for using an underline to describe soft consonants.

Grammar

Bengali nouns are not assigned gender, which leads to minimal changing of adjectives (inflection). However, nouns and pronouns are moderately declined (altered depending on their function in a sentence) into four cases while verbs are heavily conjugated, and the verbs do not change form depending on the gender of the nouns.

Word order

As a head-final language, Bengali follows a subject–object–verb word order, although variations on this theme are common.[101] Bengali makes use of postpositions, as opposed to the prepositions used in English and other European languages. Determiners follow the noun, while numerals, adjectives, and possessors precede the noun.[102]

Yes–no questions do not require any change to the basic word order; instead, the low (L) tone of the final syllable in the utterance is replaced with a falling (HL) tone. Additionally, optional particles (e.g. কি -ki, না -na, etc.) are often encliticised onto the first or last word of a yes–no question.

Wh-questions are formed by fronting the wh-word to focus position, which is typically the first or second word in the utterance.

Nouns

Nouns and pronouns are inflected for case, including nominative, objective, genitive (possessive), and locative.[29] The case marking pattern for each noun being inflected depends on the noun's degree of animacy. When a definite article such as -টা -ṭa (singular) or -গুলো -gulo (plural) is added, as in the tables below, nouns are also inflected for number.

In most of Bengali grammar books, cases are divided into 6 categories and an additional possessive case (the possessive form is not recognised as a type of case by Bengali grammarians). But in terms of usage, cases are generally grouped into only 4 categories.

|

|

When counted, nouns take one of a small set of measure words. Nouns in Bengali cannot be counted by adding the numeral directly adjacent to the noun. An appropriate measure word (MW), a classifier, must be used between the numeral and the noun (most languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area are similar in this respect). Most nouns take the generic measure word -টা -ṭa, though other measure words indicate semantic classes (e.g. -জন -jôn for humans). There is also the classifier -khana, and its diminutive form -khani, which attaches only to nouns denoting something flat, long, square, or thin. These are the least common of the classifiers.[103]

| Example |

|---|

| Script error: No such module "Interlinear". |

| Script error: No such module "Interlinear". |

| Script error: No such module "Interlinear". |

| Script error: No such module "Interlinear". |

Measuring nouns in Bengali without their corresponding measure words (e.g. আট বিড়াল aṭ biṛal instead of আটটা বিড়াল aṭ-ṭa biṛal "eight cats") would typically be considered ungrammatical. However, when the semantic class of the noun is understood from the measure word, the noun is often omitted and only the measure word is used, e.g. শুধু একজন থাকবে। Shudhu êk-jôn thakbe. (lit. "Only one-MW will remain.") would be understood to mean "Only one person will remain.", given the semantic class implicit in -জন -jôn.

In this sense, all nouns in Bengali, unlike most other Indo-European languages, are similar to mass nouns.

Verbs

There are two classes of verbs: finite and non-finite. Non-finite verbs have no inflection for tense or person, while finite verbs are fully inflected for person (first, second, third), tense (present, past, future), aspect (simple, perfect, progressive), and honour (intimate, familiar, and formal), but not for number. Conditional, imperative, and other special inflections for mood can replace the tense and aspect suffixes. The number of inflections on many verb roots can total more than 200.

Inflectional suffixes in the morphology of Bengali vary from region to region, along with minor differences in syntax.

Bengali differs from most Indo-Aryan Languages in the zero copula, where the copula or connective be is often missing in the present tense.[86] Thus, "he is a teacher" is সে শিক্ষক se shikkhôk, (literally "he teacher").[104] In this respect, Bengali is similar to Russian and Hungarian. Romani grammar is also the closest to Bengali grammar.[105]

Vocabulary

Bengali has as many as 100,000 separate words, of which 50,000 are considered Tadbhavas, 21,100 are Tatsamas and the remainder loanwords from Austroasiatic and other foreign languages. Bengali is reportedly similar to Assamese and has a lexical similarity of 40 per cent with Nepali.[106]

However, these figures do not take into account the large proportion of archaic or highly technical words that are very rarely used. Furthermore, different dialects use more Persian and Arabic vocabulary, especially in different areas of Bangladesh and Muslim majority areas of West Bengal. Hindus, on the other hand, use more Sanskrit vocabulary than Muslims. Standard Bengali is based on the Nadia dialect spoken in the Hindu-majority states of West Bengal and parts of the Muslim-majority division of Khulna in Bangladesh. About 90% of Bengalis in Bangladesh (ca. 148 million) and 27% of Bengalis in West Bengal and 10% in Assam (ca. 36 million) are Muslim and the Bangladeshi Muslims and some of the Indian Bengali Muslims speak a more "persio-arabised" version of Bengali instead of the more Sanskrit influenced Standard Nadia dialect although the majority of the Indian Bengalis of West Bengal speaks in Rarhi dialect irrespective of religion. The productive vocabulary used in modern literary works, in fact, is made up mostly (67%) of Tadbhavas, while Tatsamas make up only 25% of the total.[107][108] Loanwords from non-Indic languages account for the remaining 8% of the vocabulary used in modern Bengali literature.

According to Suniti Kumar Chatterji, dictionaries from the early 20th century attributed a little more than 50% of the Bengali vocabulary to native words (i.e., naturally modified Sanskrit words, corrupted forms of Sanskrit words, and loanwords non-Indo-European languages). About 45% per cent of Bengali words are unmodified Sanskrit, and the remaining words are from foreign languages.[109] Dominant in the last group was Persian, which was also the source of some grammatical forms. More recent studies suggest that the use of native and foreign words has been increasing, mainly because of the preference of Bengali speakers for the colloquial style.[109] Because of centuries of contact with Europeans, Turkic peoples, and Persians, Bengali has absorbed numerous words from foreign languages, often totally integrating these borrowings into the core vocabulary.

The most common borrowings from foreign languages come from three different kinds of contact. After close contact with several indigenous Austroasiatic languages,[110][111][112][113] and later the Delhi Sultanate, the Bengal Sultanate, and the Mughal Empire, whose court language was Persian, numerous Arabic, Persian, and Chaghatai words were absorbed into the lexicon.[40]

Later, East Asian travellers and lately European colonialism brought words from Portuguese, French, Dutch, and most significantly English during the colonial period.

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Bengali of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

See also

- Bangla Academy

- Bengali dialects

- Bengali numerals

- Bengali-language newspapers

- Chittagonian language

- Languages of Bangladesh

- Rangpuri language

- Romani people

- Sylheti language

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Template:E26

- ↑ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength - 2011". Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011Census/Language-2011/Statement-1.pdf.

- ↑ "Bangla Sign Language Dictionary". https://www.scribd.com/doc/251910320/Bangla-Sign-Language-Dictionary.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Jharkhand gives second language status to Magahi, Angika, Bhojpuri, and Maithili". The Avenue Mail. 21 March 2018. https://www.avenuemail.in/ranchi/jharkhand-gives-second-language-status-to-magahi-angika-bhojpuri-and-maithili/118291/.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Bengali". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/beng1280.

- ↑ "Bengal". The Chambers Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers. 2003. ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ "The World Factbook" (in en). Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/world/.

- ↑ "Summary by language size" (in en). 2019. https://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Bangla Bhasha Procholon Ain, 1987" (in bn). Bangladesh Code. 27 (Online ed.). Dhaka: Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Bangladesh. http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/pdf/705___.pdf. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Bangla Language". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangla_Language.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh". http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/act-details-367.html.

- ↑ "National Languages Of Bangladesh". 11 June 2017. https://einfon.com/nationalsymbols/national-languages-of-bangladesh/.

- ↑ "5 Surprising Reasons the Bengali Language Is Important". 17 August 2017. http://www.viadelivers.com/bengali-language-facts/.

- ↑ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)". 16 July 2014. http://nclm.nic.in/shared/linkimages/NCLM50thReport.pdf.

- ↑ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India". Ministry of Minority Affairs. http://nclm.nic.in/shared/linkimages/NCLM50thReport.pdf.

- ↑ "Bengali Language". https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bengali-language.

- ↑ —R, Aishwaryaa (6 June 2019). "What census data reveals about use of Indian languages". Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/what-census-data-reveals-about-use-of-indian-languages-738340.html.

—Pallapothu, Sravan (28 June 2018). "Hindi Added 100Mn Speakers In A Decade; Kashmiri 2nd Fast Growing Language". https://www.indiaspend.com/hindi-added-100mn-speakers-in-a-decade-kashmiri-2nd-fast-growing-language-93096/.

—IndiaSpend (2 July 2018). "Hindi fastest growing language in India, finds 100 million new speakers". Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/hindi-fastest-growing-language-in-india-finds-100-million-new-speakers-118070200029_1.html.

—Mishra, Mayank; Aggarwal, Piyush (11 April 2022). "Hindi grew rapidly in non-Hindi states even without official mandate". India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/diu/story/hindi-grows-in-non-hindi-states-without-official-mandate-1936196-2022-04-11. Retrieved 16 November 2023. - ↑ "Bangla:The French of the East". 25 February 2013. https://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-270322.

- ↑ "Amendment to the Draft Programme and Budget for 2000–2001 (30 C/5)". General Conference, 30th Session, Draft Resolution. UNESCO. 1999. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001177/117709E.pdf.

- ↑ "Resolution adopted by the 30th Session of UNESCO's General Conference (1999)". International Mother Language Day. UNESCO. http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID%3D28672%26URL_DO%3DDO_TOPIC%26URL_SECTION%3D201.html.

- ↑ (Toulmin 2009:220)

- ↑ Datta, Amaresh (1988). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Devraj to Jyoti. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1694. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=zB4n3MVozbUC&dq=Sanskrit+Brahmins+Bengal&pg=PA1694. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ↑ (in en) Journal and Text of the Buddhist Text Society of India. The Society. 1894. https://books.google.com/books?id=qxZBAQAAMAAJ&dq=Bengal+local+Buddhist+population+spoke+varieties+of+the+Prakrit&pg=RA2-PT3. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ↑ Tuteja, K. L.; Chakraborty, Kaustav (15 March 2017) (in en). Tagore and Nationalism. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 978-81-322-3696-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=iZJcDgAAQBAJ&dq=%22eastern+Magadhi+Prakrit%22+suniti+chatterjee&pg=PA59. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ↑ Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza et al., eds (2012). "Bangla Script". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangla_Script. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ↑ Shah 1998, p. 11

- ↑ Keith 1998, p. 187

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 (Bhattacharya 2000)

- ↑ "Within the Eastern Indic language family the history of the separation of Bangla from Odia, Assamese, and the languages of Bihar remains to be worked out carefully. Scholars do not yet agree on criteria for deciding if certain tenth century AD texts were in a Bangla already distinguishable from the other languages, or marked a stage at which Eastern Indic had not finished differentiating." (Dasgupta 2003:386–387)

- ↑ "Banglapedia". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php.

- ↑ "Pala dynasty – Indian dynasty". https://global.britannica.com/topic/Pala-dynasty.

- ↑ nimmi. "Pala Dynasty, Pala Empire, Pala empire in India, Pala School of Sculptures". http://www.indianmirror.com/dynasty/paladynasty.html.

- ↑ "What is more significant, a contemporary Chinese traveler reported that although Persian was understood by some in the court, the language in universal use there was Bengali. This points to the waning, although certainly not yet the disappearance, of the sort of foreign mentality that the Muslim ruling class in Bengal had exhibited since its arrival over two centuries earlier. It also points to the survival, and now the triumph, of local Bengali culture at the highest level of official society." (Eaton 1993:60)

- ↑ Rabbani, AKM Golam (7 November 2017). "Politics and Literary Activities in the Bengali Language during the Independent Sultanate of Bengal". Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics 1 (1): 151–166. https://www.banglajol.info/index.php/DUJL/article/view/3344. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Eaton 1993.

- ↑ (Eaton 1993:167–174)

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Bengali Language at Cornell". Cornell University. http://lrc.cornell.edu/asian/courses/bengali.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Ray, S Kumar. "The Bengali Language and Translation". Translation Articles. Kwintessential. http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/translation/articles/bengali-language.html.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Thompson, Hanne-Ruth (2012). Bengali (Paperback with corrections. ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co.. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-272-3819-1.

- ↑ "Bengali 'should be UN language'". 22 December 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8425744.stm.

- ↑ "UN adopts Bangla as unofficial language" (in en). 12 June 2022. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2022/06/12/un-adopts-bangla-as-unofficial-language.

- ↑ "Kuwait restricts recruitment of male Bangladeshi workers | Dhaka Tribune" (in en-US). 7 September 2016. http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2016/09/07/kuwait-restricts-imports-male-bangladeshi-workers/.

- ↑ "Bahrain: Foreign population by country of citizenship, sex and migration status (worker/ family dependent) (selected countries, January 2015) – GLMM" (in en-US). GLMM. 20 October 2015. http://gulfmigration.eu/bahrain-foreign-population-by-country-of-citizenship-sex-and-migration-status-worker-family-dependent-selected-countries-january-2015/.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia". Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/country/SA.

- ↑ "New York State Voter Registration Form". http://www.elections.ny.gov/NYSBOE/download/voting/voteform.pdf.

- ↑ "Bangla Language and Literary Society, Singapore". http://blls.sg.

- ↑ "Languages of India". Ethnologue Report. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=IN.

- ↑ "Language". http://www.assam.gov.in/language.asp.

- ↑ Bhattacharjee, Kishalay (30 April 2008). "It's Indian language vs Indian language". NDTV.com. http://www.ndtv.com/convergence/ndtv/story.aspx?id=NEWEN20080048434.

- ↑ Syed Yasir Kazmi (16 October 2009). "Pakistani Bengalis". DEMOTIX. http://www.demotix.com/news/160560/bengalis-pakistan-karachi#media-160511.

- ↑ "کراچی کے 'بنگالی پاکستانی'(Urdu)". محمد عثمان جامعی. 17 November 2003. http://www.bbc.co.uk/urdu/pakistan/story/2003/11/031117_karachi_bangali_as.shtml.

- ↑ Rafiqul Islam. "The Language Movement : An Outline". http://www.21stfebruary.org/eassy21_5.htm.

- ↑ "Karachi Department of Bengali". http://www.uok.edu.pk/faculties/bengali/.

- ↑ "Statement by Foreign Minister on Second Bangladesh-India Track II dialogue at BRAC Centre on 07 August, 2005". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh. http://www.mofa.gov.bd/statements/fm39.htm.

- ↑ "Sri Lanka". The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/sri-lanka/. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ "Man of the series: Nobel laureate Tagore". The Times of India. Times News Network. 3 April 2011. http://epaper.timesofindia.com/Repository/getFiles.asp?Style=OliveXLib:LowLevelEntityToPrint_TOINEW&Type=text/html&Locale=english-skin-custom&Path=CAP/2011/04/03&ID=Ar01601.

- ↑ "Sri Lanka I-Day to have anthem in Tamil". The Hindu. 4 February 2016. http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/sri-lanka-iday-to-have-anthem-in-tamil/article8189939.ece.

- ↑ "Tagore's influence on Lankan culture". Hindustan Times. 12 May 2010. http://www.hindustantimes.com/world/tagore-s-influence-on-lankan-culture/story-ABmSseNTEg4EFv5AAoDpbN.html.

- ↑ Wickramasinghe, Nira (2003). Dressing the Colonised Body: Politics, Clothing, and Identity in Sri Lanka. Orient Longman. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-250-2479-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wde58hbSxUEC&q=Tagore. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Wickramasinghe, Kamanthi; Perera, Yoshitha. "Sri Lankan National Anthem: can it be used to narrow the gap?". The Daily Mirror (Sri Lanka) (30 March 2015). http://mirrorcitizen.dailymirror.lk/2015/03/30/sri-lankan-national-anthem-can-it-be-used-to-narrow-the-gap/.

- ↑ Haque, Junaidul (7 May 2011). "Rabindranath: He belonged to the world". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). http://archive.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=184548.

- ↑ Habib, Haroon (17 May 2011). "Celebrating Rabindranath Tagore's legacy". The Hindu. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/celebrating-rabindranath-tagores-legacy/article2026880.ece.

- ↑ "How Bengali became an official language in Sierra Leone" (in en-US). The Indian Express. 21 February 2017. http://indianexpress.com/article/research/how-bengali-became-an-official-language-in-sierra-leone-in-west-africa-international-mother-language-day-2017-4536551/.

- ↑ "Why Bangla is an official language in Sierra Leone". Dhaka Tribune. 23 February 2017. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/foreign-affairs/2017/02/23/bangla-language-sierra-leone.

- ↑ Ahmed, Nazir (21 February 2017). "Recounting the sacrifices that made Bangla the State Language". http://thedailynewnation.com/news/125160/recounting-the-sacrifices-that-made-bangla-the-state-language.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone makes Bengali official language". Pakistan. 29 December 2002. http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=story_29-12-2002_pg9_6.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Subir (22 December 2009). "Bengali 'should be UN language'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8425744.stm.

- ↑ name="huq_sarkar"

- ↑ (in English) The Origin and Development of the Bengali language, Suniti kumar Chatterjee, Vol- 1, Page 140, George Allen and Unwin London,New Edition,1970.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza et al., eds (2012). "Dialect". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Dialect. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ↑ "Hajong". The Ethnologue Report. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=haj.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza et al., eds (2012). "Bangladesh". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangladesh. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "History of Bengali (Banglar itihash)". Bengal Telecommunication and Electric Company. http://www.betelco.com/bd/bangla/bangla.html.

- ↑ Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza et al., eds (2012). "Sadhu Bhasa". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Sadhu_Bhasa. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ↑ Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza et al., eds (2012). "Alaler Gharer Dulal". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Alaler_Gharer_Dulal. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Ray, Hai & Ray 1966, p. 89

- ↑ Ray, Hai & Ray 1966, p. 80

- ↑ "A Bilingual Dictionary of Words and Phrases (English-Bengali)". http://www.bengali-dictionary.com/english_bengali_words_phrases_relations%202.html.

- ↑ (Masica 1991)

- ↑ Sarkar, Pabitra (1985). Bangla diswar dhoni. Bhasa.

- ↑ (Masica 1991)

- ↑ Escudero Pascual Alberto (23 October 2005). "Writing Systems/ Scripts". Primer to Localization of Software. it46.se. http://www.it46.se/docs/courses/ICT4D_localization_software_primer_it46_v1.5.pdf.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Bangalah". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangalah. in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ "banglasemantics.net". http://banglasemantics.net/.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 "Bangla language". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bangla_Language. in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ Chatterji (1926), p. 234-235.

- ↑ Saha, RN (1935). "The Origin of the Alphabet and Numbers". in Khattry, DP. Report of All Asia Educational Conference (Benares, December 26-30, 1930). Allahabad, India: The Indian Press Ltd. pp. 751–779. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124177/page/n772/mode/2up.

- ↑ Chatterji (1926), pp. 228-233.

- ↑ Khan Sahib, Maulavi Abdul Wali (2 November 1925). A Bengali Book written in Persian Script. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.280407/page/n405/mode/2up.

- ↑ Ahmad, Qeyamuddin (20 March 2020). The Wahhabi Movement in India. Routledge.

- ↑ "The development of Bengali literature during Muslim rule". https://blogs.edgehill.ac.uk/sacs/files/2012/07/Document-6-Billah-A.-M.-M.-A-The-Development-of-Bengali-Literature-during-Muslim-Rule.pdf.

- ↑ Shahidullah, Muhammad (February 1963). "হযরত নূরুদ্দীন নূরুল হক নূর কুতবুল আলম (রহঃ)" (in bn). ইসলাম প্রসঙ্গ (1 ed.). Dacca: Mawla Brothers. p. 99. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.457435/page/n95/mode/2up.

- ↑ Kurzon, Dennis (2010). "Romanisation of Bengali and Other Indian Scripts". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 20 (1): 71–73. ISSN 1356-1863. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27756124. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Chatterji (1926), pp. 233-234.

- ↑ Kurzon, Dennis (2009). Romanisation of Bengali and Other Indian Scripts (Thesis). Cambridge University.

- ↑ Islam, Tahsina (18 September 2019). "The question of standard Bangla". The Independent (Dhaka). https://www.theindependentbd.com/post/215864.

- ↑ "Learning International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration". Sanskrit 3 – Learning transliteration. Gabriel Pradiipaka & Andrés Muni. http://www.sanskrit-sanscrito.com.ar/english/sanskrit/sanskrit3.html.

- ↑ "ITRANS – Indian Language Transliteration Package". Avinash Chopde. http://www.aczoom.com/itrans/.

- ↑ "Annex-F: Roman Script Transliteration". Indian Standard: Indian Script Code for Information Interchange – ISCII. Bureau of Indian Standards. 1 April 1999. p. 32. http://varamozhi.sourceforge.net/iscii91.pdf.

- ↑ (Bhattacharya 2000)

- ↑ "Bengali". UCLA Language Materials project. University of California, Los Angeles. http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=84&menu=004.

- ↑ Boyle David, Anne (2015). Descriptive grammar of Bangla. De Gruyter. pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Among Bengali speakers brought up in neighbouring linguistic regions (e.g. Hindi), the lost copula may surface in utterances such as she shikkhôk hocche. This is viewed as ungrammatical by other speakers, and speakers of this variety are sometimes (humorously) referred as "hocche-Bangali".

- ↑ Hübschmannová, Milena (1995). "Romaňi čhib – romština: Několik základních informací o romském jazyku". Bulletin Muzea Romské Kultury (Brno) (4/1995). "Zatímco romská lexika je bližší hindštině, marvárštině, pandžábštině atd., v gramatické sféře nacházíme mnoho shod s východoindickým jazykem, s bengálštinou.".

- ↑ "Bengali". Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/language/ben/.

- ↑ "Tatsama". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Tatsama. in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ "Tadbhaba". http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Tadbhaba. in Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2003

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Bengali language". https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bengali-language.

- ↑ Byomkes Chakrabarti A Comparative Study of Santali and Bengali, K.P. Bagchi & Co., Kolkata, 1994, ISBN:81-7074-128-9

- ↑ Das, Khudiram (1998). Santhali Bangla Samashabda Abhidhan. Kolkata, India: Paschim Banga Bangla Akademi.

- ↑ "Bangla santali vasa samporko". http://professorkhudiramdas.com/files/ebooks/Bangla-santali-vasa-samporko-by-khudiram-das.pdf.

- ↑ Das, Khudiram. Bangla Santali Bhasa Samporko (eBook).

References

|

|

Further reading

- Thompson, Hanne-Ruth (2012). Bengali. Volume 18 of London Oriental and African Language Library. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN:90-272-7313-8.

External links

- Bengali language at Curlie

- The South Asian Literary Recordings Project: Bengali Authors at the Library of Congress

- REDIRECT Template:Bengali language

- From a page move: This is a redirect from a page that has been moved (renamed). This page was kept as a redirect to avoid breaking links, both internal and external, that may have been made to the old page name.

|