Physics:B Reactor

B Reactor | |

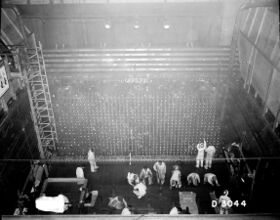

The face of B Reactor during construction. | |

| Location | About 5.3 mi (8.5 km) northeast of junction of State Route 24 and State Route 240 on the Hanford Site |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Richland, Washington |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 46°37′49″N 119°38′50″W / 46.63028°N 119.64722°W |

| Area | 9.5 acres (3.8 ha) |

| Built | June 7, 1943[1] to September 1944[2] |

| Architect | E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company |

| NRHP reference # | 92000245 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 3, 1992 |

| Designated NHL | August 19, 2008[3] |

The B Reactor at the Hanford Site, near Richland, Washington, was the first large-scale nuclear reactor ever built. The project was a key part of the Manhattan Project, the United States nuclear weapons development program during World War II. Its purpose was to convert natural (not isotopically enriched) uranium metal into plutonium-239 by neutron activation, as plutonium is simpler to chemically separate from spent fuel assemblies, for use in nuclear weapons, than it is to isotopically enrich uranium into weapon-grade material. The B reactor was fueled with metallic natural uranium, graphite moderated, and water-cooled. It has been designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark since August 19, 2008[3][4] and in July 2011 the National Park Service recommended that the B Reactor be included in the Manhattan Project National Historical Park commemorating the Manhattan Project.[5] Visitors can take a tour of the reactor by advance reservation.[6]

Design and construction

The reactor was designed and built by E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company based on experimental designs tested by Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago, and tests from the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. It was designed to operate at 250 megawatts (thermal).

The purpose of the reactor was to breed plutonium from natural (not isotopically enriched) uranium metal, as uranium enrichment was a difficult process, while plutonium is relatively simple to process chemically. The Y12 uranium enrichment plant required 14,700 tons of silver for its enrichment calutrons, as well as 22,000 employees and more electrical power than most entire states required at the time. Reactor B required only a few dozen employees and fewer exotic materials, which were also required in far smaller amounts. The largest part of the reactor was 1200 tons of graphite used as a moderator, and its power consumption was vastly smaller, requiring only enough electricity to run the cooling pumps.[7][8]

The reactor occupies a footprint of 46 by 38 ft (14 by 12 m) (about 1,750 sq ft (163 m2) and is 41 ft (12 m) tall, occupying a volume of 71,500 cu ft (2,020 m3). The reactor core itself consisted of a 36 ft-tall (11 m) graphite box measuring 28 by 36 ft (8.5 by 11.0 m) occupying a volume of 36,288 cu ft (1,027.6 m3) and weighing 1,200 short tons (1,100 t). It was penetrated horizontally through its entire length by 2,004 aluminum tubes and vertically by channels for the vertical safety rods.[4]

The core is surrounded by a thermal shield of cast iron 8 to 10 in (20 to 25 cm) thick weighing 1,000 short tons (910 t). Masonite and steel plates enclose the thermal shield on its top and sides, forming a biological shield for radiation protection. The bottom of the thermal shield is supported by a 23 ft-thick (7.0 m) concrete pad topped by cast-iron blocks. The graphite composition was selected to moderate the nuclear reaction fueled by 200 short tons (180 t) of uranium slugs approximately 25 mm (1 in) diameter 70 mm (3 in) long (the approximate size of a roll of quarters[4]), sealed in aluminum cans, and loaded into the aluminum tubes.[4]

The reactor was water-cooled, with cooling water pumped from the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River through the aluminum tubes around the uranium slugs at the rate of 75,000 US gal (280,000 L) per minute. The water was discharged into settling basins, then returned to the river after allowing time for the decay of radioactive materials, the settling out of particulate matter, and for the water to cool so it could be returned to the Columbia River. Water returning to the river was prohibited from raising the temperature of the river by more than 11 °F.[9]

Operation

The B Reactor had its first nuclear chain reaction in September 1944, the D Reactor in December 1944 and the F Reactor in February 1945. The initial operation was halted by a problem identified as neutron absorption by the fission product Xe-135, first identified in a research paper of Chien-Shiung Wu that was shared with Fermi.[10] It was overcome by increasing the amount of uranium charged. The reactor produced plutonium-239 by irradiating uranium-238 with neutrons generated by the nuclear reaction. It was one of three reactors – along with the D and F reactors – built about six miles (10 km) apart on the south bank of the Columbia River. Each reactor had its own auxiliary facilities that included a river pump house, large storage and settling basins, a filtration plant, large motor-driven pumps for delivering water to the face of the pile, and facilities for emergency cooling in case of a power failure.[4]

Emergency shutdown of the reactor, referred to as a SCRAM, was attained either by rapidly fully inserting the vertical safety rods or, as a backup method, by the injection of borated water into the reactor. In January 1952, the borated water system was replaced by a "Ball-3X" system that injected nickel-plated high-boron steel balls into the channels occupied by the vertical safety rods.[4]

The plutonium for the nuclear bomb used in the Trinity test in New Mexico and the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan was created in the B reactor. The B Reactor ran for two decades, and was joined by additional reactors constructed later. It was permanently shut down in February 1968.[4][11]

Current status

The United States Department of Energy has administered the site since 1977[12][13] and offers public tours on set dates during the spring, summer, and fall of the year, as well as special tours for visiting officials.[6][14]

As of 2014[update] six of the nine production reactors at Hanford were considered to be in "interim safe storage" status, and two more were to receive similar treatment. The exception was the B Reactor, which was given special status for its historical significance.[15]

In a process called cocooning or entombment, the reactor buildings are demolished up to the 4 ft-thick (1.2 m) concrete shield around the reactor core. Any openings are sealed and a new roof is built.[16] Most auxiliary buildings at the first three reactors have been demolished, as well. The C reactor was put into operation in 1952 and was shut down in 1969.[17] It was cocooned as of 1998.[18] The D reactor operated from 1944 to June 1967, and was cocooned in 2004. The DR Reactor went online in October 1950,[19] and was shut down in 1964. It was cocooned in 2002.[20] The F reactor was shut down in June 1965 and cocooned in 2003.[21] The H Reactor became operational as of October 1949 and was shut down as of April 1965. It was cocooned as of 2005.[22] Cocooning of the N-Reactor, which operated from 1963 to 1987, was completed as of June 14, 2012.[23] The decommissioned reactors are inspected every five years by the Department of Energy.[18]

The K East and K West reactors were built in the 1950s and went into use in 1955. They were shut down in 1970 and 1971, but reused temporarily for storage later.[24] Preliminary plans for interim stabilizing of the K-East and K-West reactors were underway as of January 30, 2018.[16]

The B Reactor was added to the National Register of Historic Places (#92000245) on April 3, 1992. A Record of Decision (ROD) was issued in 1999, and an EPA Action Memorandum in 2001 authorized hazards mitigation in the reactor with the intention of allowing public tours of the reactor.[25] It was named a National Historic Landmark on August 19, 2008.[3][4]

In December 2014, passage of the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) made the B reactor part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, which also includes historic sites at Oak Ridge, Tennessee and Los Alamos, New Mexico.[26][27] The park was formally established by a Memorandum of Agreement on November 10, 2015, which was signed by the National Park Service and the Department of Energy. Museum development at Hanford may include the B Reactor, Bruggemann's Warehouse, Hanford High School, Pump House, and White Bluffs Bank.[28]

Timeline of major events

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1943 | October | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers breaks ground to build B Reactor[29] |

| 1944 | September 13 | First uranium fuel slug loaded into B Reactor[29] |

| 1944 | September 26 | Initial reactor criticality achieved[29] |

| 1945 | February 3 | B Reactor plutonium delivered to Los Alamos[29] |

| 1945 | July 16 | B Reactor plutonium used in world's first nuclear explosion. (Trinity Test Site, New Mexico) [29] |

| 1945 | August 9 | B Reactor plutonium used in Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan[29] |

| 1946 | March | B Reactor operations suspended[29] |

| 1948 | June | B Reactor operation resumed[29] |

| 1949 | March | B Reactor begins production of tritium for use in hydrogen bombs[29] |

| 1954 | March 1 | First use of B Reactor tritium in a test detonation of a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll[citation needed] |

| 1968 | January 29 | Atomic Energy Commission directs shutdown of B Reactor[29] |

| 1976 | B Reactor declared National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by American Society of Mechanical Engineers[29] | |

| 1994 | B Reactor declared National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by American Society of Civil Engineers[29] | |

| 2008 | B Reactor declared National Historic Landmark by U.S. Department of Interior and National Park Service[29] | |

| 2009 | U.S. Department of Energy announces public tours[30] | |

| 2011 | July | National Park Service recommends B Reactor be included in a national historic park commemorating the Manhattan Project.[5] |

| 2014 | December | 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) includes B reactor in Manhattan Project National Historical Park[26] |

| 2015 | November 10 | Manhattan Project National Historical Park formally established by Memorandum of Agreement[28] |

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Washington

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Benton County, Washington

References

- ↑ Shannon Dininny (2008-08-26). "World's first nuclear reactor now a landmark". Associated Press. https://www.energy.gov/about/breactor.htm. "Construction began on June 7, 1943..."

- ↑ "Department of Energy – B Reactor". United States Department of Energy. 2007-04-20. https://www.energy.gov/about/breactor.htm. "Completed in September 1944..."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Weekly List Actions". National Park Service. 2008-08-29. http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/listings/20080829.HTM.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Michele S. Gerber; Brian Casserly; Frederick L. Brown (February 2007). National Historic Landmark Nomination: B Reactor / 105-B; The 105-B Building in the 100-B/C Area at Hanford. National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/Fall07Nominations/B%20Reactor.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cary, Annette (13 July 2011). "HANFORD: Park service recommends B Reactor for national park". Tri-City Herald. http://www.tri-cityherald.com/2011/07/13/1565637/hanford-park-service-recommends.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "The B Reactor National Historic Landmark". Manhattan Project: B Reactor. http://manhattanprojectbreactor.hanford.gov/.

- ↑ The New World 1939, Page 71, Richard G. Hewlett, 1972

- ↑ "B Reactor". U.S. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/management/b-reactor.

- ↑ United States Department of Energy. "Hanford Site Virtual Tours: 100-B Area". Hanford Site website. Richland, Washington. http://www.hanford.gov/?page=347&parent=326.

- ↑ Dicke, William (1997-02-18). "Chien-Shiung Wu, 84, Top Experimental Physicist". http://cwp.library.ucla.edu/articles/wuobit.html.

- ↑ Boyle, Rebecca (2017). "Greetings from Isotopia". Distillations 3 (3): 26–35. https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/greetings-from-isotopia. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ↑ Long, Tony (August 4, 1977). "All U.S. Energy Placed Under Single Roof". Wired.com. https://www.wired.com/2011/08/0804us-energy-dept-created-doe/.

- ↑ "S. 826 — 95th Congress: Department of Energy Organization Act". 1977. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/95/s826.

- ↑ "Hanford Site Tours". https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/hanfordsitetours.

- ↑ National Research Council (2014). Best Practices for Risk-Informed Decision Making Regarding Contaminated Sites: Summary of a Workshop Series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-30305-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=uSdfBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT68. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Office of Environmental Management (January 30, 2018). "Hanford Workers Enter Reactor to Prepare for Cocooning". Energy.gov. https://www.energy.gov/em/articles/hanford-workers-enter-reactor-prepare-cocooning.

- ↑ "C Reactor". https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/CReactor.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cary, Annette (July 4, 2015). "Looking inside Hanford's cocooned reactors". Tri-City Herald. http://www.tri-cityherald.com/news/local/hanford/article32231739.html.

- ↑ "D and DR Reactors". https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/DDRReactors.

- ↑ "ISS Reactors". https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/LTSTransition/ISSReactors#DR_Reactor.

- ↑ Cary, Annette (October 22, 2014). "Hanford's F Reactor passes 5-year inspection". Tri-City Herald. http://www.tri-cityherald.com/news/local/hanford/article32203065.html.

- ↑ "H Reactor". https://www.hanford.gov/page.cfm/HReactor.

- ↑ Office of Environmental Management (June 14, 2012). "N Reactor Placed In Interim Safe Storage: Largest Hanford Reactor Cocooning Project Now Complete". Energy.gov. https://www.energy.gov/em/articles/hanford-workers-enter-reactor-prepare-cocooning.

- ↑ Gerber, Michele Stenehjem (2007). On the home front : the cold war legacy of the Hanford nuclear site (3rd ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0803259959. https://books.google.com/books?id=3Y33xWBvyb0C&pg=PA227. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ Potter, Robert F.. "Preserving the Hanford B-Reactor: A Monument to the Dawn of the Nuclear Age". https://www.aps.org/units/fps/newsletters/201001/potter.cfm.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Congress Passes Manhattan Project National Historical Park Act". December 12, 2014. https://www.atomicheritage.org/article/congress-passes-manhattan-project-national-historical-park-act.

- ↑ "B Reactor Museum Association Richland, Washington, USA". http://b-reactor.org/.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Foundation Document Manhattan Project National Historical Park Tennessee, New Mexico, Washington". January 2017. p. 33. https://www.nps.gov/mapr/upload/MAPR_FD_PRINT.pdf.

- ↑ 29.00 29.01 29.02 29.03 29.04 29.05 29.06 29.07 29.08 29.09 29.10 29.11 29.12 Ms, Gerber (May 2009), Manhattan Project B Reactor: World's first full-scale nuclear reactor, HNF-41115, Rev. 0, US Department of Energy

- ↑ Manhattan Project B Reactor Tour Information, Feb 14, 2011, http://manhattanprojectbreactor.hanford.gov/, retrieved 17 July 2011

Further reading

- Washington Closure Hanford- "Project News Volume 1, Issue 04". http://www.washingtonclosure.com/documents/newsletter/Vol_01_Issue_04.pdf.

- "Hanford Site – Timeline 1943–1990". 1997. http://www.hanford.gov/doe/history/docs/rl-97-1047/dates.pdf.

- History of the 100-B area (Report). US DoE. WHC-EP-0273. http://www.osti.gov/manhattan-project-history/publications/DOEHistory100B.pdf.

External links

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. WA-164, "B Reactor, Richland, Benton County, WA", 32 photos, 148 data pages, 4 photo caption pages

- "Ranger in Your Pocket" online tours Atomic Heritage Foundation

- Hanford 25th Anniversary Celebration Video of the 25th anniversary celebration of the construction of B Reactor

- B Reactor Museum Association A collection of Hanford-related documents from a group working to preserve the B-100 Reactor at Hanford.

- Hanford Site Tours – Department of Energy, includes B Reactor

|