Physics:Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation

In heat transfer, Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation refers to wavelength-specific radiative emission and absorption by a material body in thermodynamic equilibrium, including radiative exchange equilibrium. It is a special case of Onsager reciprocal relations as a consequence of the time reversibility of microscopic dynamics, also known as microscopic reversibility.

A body at temperature T radiates electromagnetic energy. A perfect black body in thermodynamic equilibrium absorbs all light that strikes it, and radiates energy according to a unique law of radiative emissive power for temperature T (Stefan–Boltzmann law), universal for all perfect black bodies. Kirchhoff's law states that:

Here, the dimensionless coefficient of absorption (or the absorptivity) is the fraction of incident light (power) that is absorbed by the body when it is radiating and absorbing in thermodynamic equilibrium.

In slightly different terms, the emissive power of an arbitrary opaque body of fixed size and shape at a definite temperature can be described by a dimensionless ratio, sometimes called the emissivity: the ratio of the emissive power of the body to the emissive power of a black body of the same size and shape at the same fixed temperature. With this definition, Kirchhoff's law states, in simpler language:

In some cases, emissive power and absorptivity may be defined to depend on angle, as described below. The condition of thermodynamic equilibrium is necessary in the statement, because the equality of emissivity and absorptivity often does not hold when the material of the body is not in thermodynamic equilibrium.

Kirchhoff's law has another corollary: the emissivity cannot exceed one (because the absorptivity cannot, by conservation of energy), so it is not possible to thermally radiate more energy than a black body, at equilibrium. In negative luminescence the angle and wavelength integrated absorption exceeds the material's emission; however, such systems are powered by an external source and are therefore not in thermodynamic equilibrium.

History

Before Kirchhoff's law was recognized, it had been experimentally established that a good absorber is a good emitter, and a poor absorber is a poor emitter. Naturally, a good reflector must be a poor absorber. This is why, for example, lightweight emergency thermal blankets are based on reflective metallic coatings: they lose little heat by radiation.

Kirchhoff's great insight was to recognize the universality and uniqueness of the function that describes the black body emissive power. But he did not know the precise form or character of that universal function. Attempts were made by Lord Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans 1900–1905 to describe it in classical terms, resulting in Rayleigh–Jeans law. This law turned out to be inconsistent yielding the ultraviolet catastrophe. The correct form of the law was found by Max Planck in 1900, assuming quantized emission of radiation, and is termed Planck's law.[7] This marks the advent of quantum mechanics.

Theory

In a blackbody enclosure that contains electromagnetic radiation with a certain amount of energy at thermodynamic equilibrium, this "photon gas" will have a Planck distribution of energies.[8]

One may suppose a second system, a cavity with walls that are opaque, rigid, and not perfectly reflective to any wavelength, to be brought into connection, through an optical filter, with the blackbody enclosure, both at the same temperature. Radiation can pass from one system to the other. For example, suppose in the second system, the density of photons at narrow frequency band around wavelength [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] were higher than that of the first system. If the optical filter passed only that frequency band, then there would be a net transfer of photons, and their energy, from the second system to the first. This is in violation of the second law of thermodynamics, which requires that there can be no net transfer of heat between two bodies at the same temperature.

In the second system, therefore, at each frequency, the walls must absorb and emit energy in such a way as to maintain the black body distribution.[9] Hence absorptivity and emissivity must be equal. The absorptivity [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_\lambda }[/math] of the wall is the ratio of the energy absorbed by the wall to the energy incident on the wall, for a particular wavelength. Thus the absorbed energy is [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_\lambda E_{b \lambda}(\lambda,T) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ E_{b \lambda}(\lambda,T) }[/math] is the intensity of black-body radiation at wavelength [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] and temperature [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]. Independent of the condition of thermal equilibrium, the emissivity of the wall is defined as the ratio of emitted energy to the amount that would be radiated if the wall were a perfect black body. The emitted energy is thus [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_\lambda E_{b \lambda}(\lambda,T) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_\lambda }[/math] is the emissivity at wavelength [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math]. For the maintenance of thermal equilibrium, these two quantities must be equal, or else the distribution of photon energies in the cavity will deviate from that of a black body. This yields Kirchhoff's law:

[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_\lambda = \varepsilon_\lambda }[/math]

By a similar, but more complicated argument, it can be shown that, since black-body radiation is equal in every direction (isotropic), the emissivity and the absorptivity, if they happen to be dependent on direction, must again be equal for any given direction.[10]

Average and overall absorptivity and emissivity data are often given for materials with values which differ from each other. For example, white paint is quoted as having an absorptivity of 0.16, while having an emissivity of 0.93.[11] This is because the absorptivity is averaged with weighting for the solar spectrum, while the emissivity is weighted for the emission of the paint itself at normal ambient temperatures. The absorptivity quoted in such cases is being calculated by:

[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{\mathrm{sun}}=\displaystyle\frac{\int_0^\infty \alpha_\lambda(\lambda)I_{\lambda \mathrm{sun}} (\lambda)\,d\lambda} {\int_0^\infty I_{\lambda \mathrm{sun}}(\lambda)\,d\lambda} }[/math]

while the average emissivity is given by:

[math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_{\mathrm{paint}}=\frac{\int_0^\infty \varepsilon_\lambda (\lambda,T) E_{b\lambda}(\lambda,T)\,d\lambda}{\int_0^\infty E_{b \lambda}(\lambda,T)\,d\lambda} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ I_{\lambda \mathrm{sun}} }[/math] is the emission spectrum of the sun, and [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_\lambda E_{b \lambda}(\lambda,T) }[/math] is the emission spectrum of the paint. Although, by Kirchhoff's law, [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_\lambda=\alpha_\lambda }[/math] in the above equations, the above averages [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{\mathrm{sun}} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_{\mathrm{paint}} }[/math] are not generally equal to each other. The white paint will serve as a very good insulator against solar radiation, because it is very reflective of the solar radiation, and although it therefore emits poorly in the solar band, its temperature will be around room temperature, and it will emit whatever radiation it has absorbed in the infrared, where its emission coefficient is high.

Black bodies

Near-black materials

It has long been known that a lamp-black coating will make a body nearly black. Some other materials are nearly black in particular wavelength bands. Such materials do not survive all the very high temperatures that are of interest.

An improvement on lamp-black is found in manufactured carbon nanotubes. Nano-porous materials can achieve refractive indices nearly that of vacuum, in one case obtaining average reflectance of 0.045%.[12][13]

Opaque bodies

Bodies that are opaque to thermal radiation that falls on them are valuable in the study of heat radiation. Planck analyzed such bodies with the approximation that they be considered topologically to have an interior and to share an interface. They share the interface with their contiguous medium, which may be rarefied material such as air, or transparent material, through which observations can be made. The interface is not a material body and can neither emit nor absorb. It is a mathematical surface belonging jointly to the two media that touch it. It is the site of refraction of radiation that penetrates it and of reflection of radiation that does not. As such it obeys the Helmholtz reciprocity principle. The opaque body is considered to have a material interior that absorbs all and scatters or transmits none of the radiation that reaches it through refraction at the interface. In this sense the material of the opaque body is black to radiation that reaches it, while the whole phenomenon, including the interior and the interface, does not show perfect blackness. In Planck's model, perfectly black bodies, which he noted do not exist in nature, besides their opaque interior, have interfaces that are perfectly transmitting and non-reflective.[2]

Cavity radiation

The walls of a cavity can be made of opaque materials that absorb significant amounts of radiation at all wavelengths. It is not necessary that every part of the interior walls be a good absorber at every wavelength. The effective range of absorbing wavelengths can be extended by the use of patches of several differently absorbing materials in parts of the interior walls of the cavity. In thermodynamic equilibrium the cavity radiation will precisely obey Planck's law. In this sense, thermodynamic equilibrium cavity radiation may be regarded as thermodynamic equilibrium black-body radiation to which Kirchhoff's law applies exactly, though no perfectly black body in Kirchhoff's sense is present.

A theoretical model considered by Planck consists of a cavity with perfectly reflecting walls, initially with no material contents, into which is then put a small piece of carbon. Without the small piece of carbon, there is no way for non-equilibrium radiation initially in the cavity to drift towards thermodynamic equilibrium. When the small piece of carbon is put in, it transduces amongst[clarify] radiation frequencies so that the cavity radiation comes to thermodynamic equilibrium.[2]

A hole in the wall of a cavity

For experimental purposes, a hole in a cavity can be devised to provide a good approximation to a black surface, but will not be perfectly Lambertian, and must be viewed from nearly right angles to get the best properties. The construction of such devices was an important step in the empirical measurements that led to the precise mathematical identification of Kirchhoff's universal function, now known as Planck's law.

Kirchhoff's perfect black bodies

Planck also noted that the perfect black bodies of Kirchhoff do not occur in physical reality. They are theoretical fictions. Kirchhoff's perfect black bodies absorb all the radiation that falls on them, right in an infinitely thin surface layer, with no reflection and no scattering. They emit radiation in perfect accord with Lambert's cosine law.[1][2]

Original statements

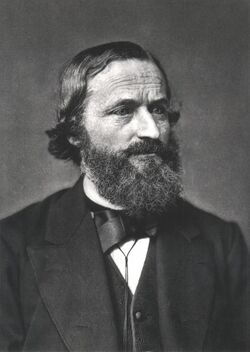

Gustav Kirchhoff stated his law in several papers in 1859 and 1860, and then in 1862 in an appendix to his collected reprints of those and some related papers.[14]

Prior to Kirchhoff's studies, it was known that for total heat radiation, the ratio of emissive power to absorptive ratio was the same for all bodies emitting and absorbing thermal radiation in thermodynamic equilibrium. This means that a good absorber is a good emitter. Naturally, a good reflector is a poor absorber. For wavelength specificity, prior to Kirchhoff, the ratio was shown experimentally by Balfour Stewart to be the same for all bodies, but the universal value of the ratio had not been explicitly considered in its own right as a function of wavelength and temperature.

Kirchhoff's original contribution to the physics of thermal radiation was his postulate of a perfect black body radiating and absorbing thermal radiation in an enclosure opaque to thermal radiation and with walls that absorb at all wavelengths. Kirchhoff's perfect black body absorbs all the radiation that falls upon it.

Every such black body emits from its surface with a spectral radiance that Kirchhoff labeled I (for specific intensity, the traditional name for spectral radiance).

The precise mathematical expression for that universal function I was very much unknown to Kirchhoff, and it was just postulated to exist, until its precise mathematical expression was found in 1900 by Max Planck. It is nowadays referred to as Planck's law.

Then, at each wavelength, for thermodynamic equilibrium in an enclosure, opaque to heat rays, with walls that absorb some radiation at every wavelength:

See also

- Kirchhoff's laws (disambiguation)

- Sakuma–Hattori equation

- Wien's displacement law

- Stefan–Boltzmann law, which states that the power of emission is proportional to the fourth power of the black body's temperature

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kirchhoff 1860

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Planck 1914

- ↑ Milne 1930, p. 80

- ↑ Chandrasekhar 1960, p. 8

- ↑ Mihalas & Weibel-Mihalas 1984, p. 328

- ↑ Goody & Yung 1989, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Kangro 1976

- ↑ Rybicki & Lightman 1979, pp. 15–20

- ↑ Rybicki & Lightman 1979, p. [page needed]

- ↑ Rybicki & Lightman 1979, p. [page needed]

- ↑ "The Solar-AC FAQ: Table of absorptivity and emissivity of common materials and coatings". http://www.solarmirror.com/fom/fom-serve/cache/43.html.

- ↑ Chun 2008

- ↑ Yang et al.

- ↑ Kirchhoff 1862

Bibliography

- Chandrasekhar, S. (1960). Radiative Transfer (Revised reprint ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-60590-6. https://archive.org/details/radiativetransfe0000chan.

- Chun, A.i L. (2008). "Carbon nanotubes: Blacker than black". Nature Nanotechnology. doi:10.1038/nnano.2008.29.

- Goody, R. M.; Yung, Y. L. (1989). Atmospheric Radiation: Theoretical Basis (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510291-8.

- Kangro, H. (1976). Early History of Planck's Radiation Law. translated by R.E.W Madison, with the cooperation of Kangro, from the 1970 German. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-85066-063-7.

- Kirchhoff, G. (1860). "Ueber das Verhältniss zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper für Wärme and Licht". Annalen der Physik und Chemie 109 (2): 275–301. doi:10.1002/andp.18601850205. Bibcode: 1860AnP...185..275K.

- Translated: Kirchhoff, G. (1860). "On the relation between the radiating and absorbing powers of different bodies for light and heat". Philosophical Magazine. Series 4 20: 1–21.

- Kirchhoff, Gustav (1862) (in de). Untersuchungen über das Sonnenspectrum und die Spectren der chemischen Elemente. Berlin: Ferd. Dümmler's Verlagsbuchhandlung. Appendix, Über das Verhältniß zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper für Wärme und Licht, pp. 22–39. ISBN 3-535-00820-4.

- Reprinted as Kirchhoff, Gustav; Kangro, Hans (1972) (in de). Untersuchungen über das Sonnenspectrum und die Spectren der chemischen Elemente und weitere ergänzende Arbeiten aus den Jahren 1859-1862. Osnabrück: Otto Zeller Verlag. Appendix, Über das Verhältniß zwischen dem Emissionsvermögen und dem Absorptionsvermögen der Körper für Wärme und Licht, pp. 45–64. ISBN 9783535008208.

- Mihalas, D.; Weibel-Mihalas, B. (1984). Foundations of Radiation Hydrodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503437-6.

- Milne, E.A. (1930). "Thermodynamics of the Stars". Handbuch der Astrophysik. Vol. 3, part 1. pp. 63–255.

- Planck, M. (1914). The Theory of Heat Radiation (2nd ed.). P. Blakiston's Son & Co.. https://archive.org/details/theoryofheatradi00planrich.

- Rybicki, George B.; Lightman, Alan P. (1979). Radiative Processes in Astrophysics. John Wiley and Sons.

- Yang, Z.-P.; Ci, L.; Bur, J. A.; Lin, S.-Y.; Ajayan, P. M. (2008). "Experimental Observation of an Extremely Dark Material Made by a Low-Density Nanotube Array". Nano Letters 8 (2): 446–51. doi:10.1021/nl072369t. PMID 18181658. Bibcode: 2008NanoL...8..446Y.

General references

- Evgeny Lifshitz and L. P. Pitaevskii, Statistical Physics: Part 2, 3rd edition (Elsevier, 1980).

- F. Reif, Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics (McGraw-Hill: Boston, 1965).

|