Physics:Photocatalytic water splitting

Photocatalytic water splitting is a process that uses photocatalysis for the dissociation of water (H2O) into hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2). Only light energy (photons), water, and a catalyst(s) are needed, since this is what naturally occurs in natural photosynthetic oxygen production and CO2 fixation.[1][2][3][4] Photocatalytic water splitting is done by dispersing photocatalyst particles in water or depositing them on a substrate, unlike Photoelectrochemical cell, which are assembled into a cell with a photoelectrode.[5][6]

Hydrogen fuel production using water and light (photocatalytic water splitting), instead of petroleum, is an important renewable energy strategy.

Concepts

Two mole of H

2O is split into 1 mole O2 and 2 mole H2 using light in the process shown below.

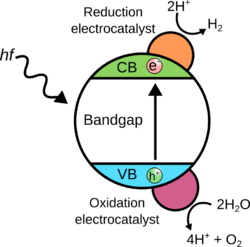

A photon with an energy greater than 1.23 eV is needed to generate an electron–hole pairs, which react with water on the surface of the photocatalyst. The photocatalyst must have a bandgap large enough to split water; in practice, losses from material internal resistance and the overpotential of the water splitting reaction increase the required bandgap energy to 1.6–2.4 eV to drive water splitting.[5]

The process of water-splitting is a highly endothermic process (ΔH > 0). Water splitting occurs naturally in photosynthesis when the energy of four photons is absorbed and converted into chemical energy through a complex biochemical pathway (Dolai's or Kok's S-state diagrams).[7]

O–H bond homolysis in water requires energy of 6.5 - 6.9 eV (UV photon).[8][9] Infrared light has sufficient energy to mediate water splitting because it technically has enough energy for the net reaction. However, it does not have enough energy to mediate the elementary reactions leading to the various intermediates involved in water splitting (this is why there is still water on Earth). Nature overcomes this challenge by absorbing four visible photons. In the laboratory, this challenge is typically overcome by coupling the hydrogen production reaction with a sacrificial reductant other than water.[10]

Materials used in photocatalytic water splitting fulfill the band requirements and typically have dopants and/or co-catalysts added to optimize their performance. A sample semiconductor with the proper band structure is titanium dioxide (TiO2) and is typically used with a co-catalyst such as platinum (Pt) to increase the rate of H2 production.[11] A major problem in photocatalytic water splitting is photocatalyst decomposition and corrosion.[11]

Method of evaluation

Photocatalysts must conform to several key principles in order to be considered effective at water splitting. A key principle is that H2 and O2 evolution should occur in a stoichiometric 2:1 ratio; significant deviation could be due to a flaw in the experimental setup and/or a side reaction, neither of which indicate a reliable photocatalyst for water splitting. The prime measure of photocatalyst effectiveness is quantum yield (QY), which is:

- QY (%) = (Photochemical reaction rate) / (Photon absorption rate) × 100%[11]

To assist in comparison, the rate of gas evolution can also be used. A photocatalyst that has a high quantum yield and gives a high rate of gas evolution is a better catalyst.

The other important factor for a photocatalyst is the range of light that is effective for operation. For example, a photocatalyst is more desirable to use visible photons than UV photons.

Photocatalysts

The solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency of photocatalytic water splitting, however, has remained very low. Here we have developed a strategy to achieve a high STH efficiency of 9.2 per cent using pure water, concentrated solar light and an indium gallium nitride photocatalyst. The success of this strategy originates from the synergistic effects of promoting forward hydrogen–oxygen evolution and inhibiting the reverse hydrogen–oxygen recombination by operating at an optimal reaction temperature (about 70 degrees Celsius), which can be directly achieved by harvesting the previously wasted infrared light in sunlight. Moreover, this temperature-dependent strategy also leads to an STH efficiency of about 7 per cent from widely available tap water and sea water and an STH efficiency of 6.2 per cent in a large-scale photocatalytic water-splitting system with a natural solar light capacity of 257 watts. Our study offers a practical approach to produce hydrogen fuel efficiently from natural solar light and water, overcoming the efficiency bottleneck of solar hydrogen production.[12]

NaTaO3:La

NaTaO3:La yielded the highest water splitting rate of photocatalysts without using sacrificial reagents.[11] This ultraviolet-based photocatalyst was reported to show water splitting rates of 9.7 mmol/h and a quantum yield of 56%. The nanostep structure of the material promotes water splitting as edges functioned as H2 production sites and the grooves functioned as O2 production sites. Addition of NiO particles as co-catalysts assisted in H2 production; this step used an impregnation method with an aqueous solution of Ni(NO3)2•6H2O and evaporated the solution in the presence of the photocatalyst. NaTaO3 has a conduction band higher than that of NiO, so photo-generated electrons are more easily transferred to the conduction band of NiO for H2 evolution.[13]

K3Ta3B2O12

K3Ta3B2O12 is another catalyst solely activated by UV and above light. It does not have the performance or quantum yield of NaTaO3:La. However, it can split water without the assistance of co-catalysts and gives a quantum yield of 6.5%, along with a water splitting rate of 1.21 mmol/h. This ability is due to the pillared structure of the photocatalyst, which involves TaO6 pillars connected by BO3 triangle units. Loading with NiO did not assist the photocatalyst due to the highly active H2 evolution sites.[14]

(Ga.82Zn.18)(N.82O.18)

(Ga.82Zn.18)(N.82O.18) had the highest quantum yield in visible light for visible light-based photocatalysts that do not utilize sacrificial reagents as of October 2008.[11] The photocatalyst featured a quantum yield of 5.9% and a water splitting rate of 0.4 mmol/h. Tuning the catalyst was done by increasing calcination temperatures for the final step in synthesizing the catalyst. Temperatures up to 600 °C helped to reduce the number of defects, while temperatures above 700 °C destroyed the local structure around zinc atoms and were thus undesirable. The treatment ultimately reduced the amount of surface Zn and O defects, which normally function as recombination sites, thus limiting photocatalytic activity. The catalyst was then loaded with Rh2-yCryO3 at a rate of 2.5 wt% Rh and 2 wt% Cr for better performance.[15]

Molecular catalysts

Proton reduction catalysts based on earth-abundant elements[16][17] carry out one side of the water-splitting half-reaction.

A mole of octahedral nickel(II) complex, [Ni(bztpen)]2+ (bztpen = N-benzyl-N,N’,N’-tris(pyridine-2-ylmethyl)ethylenediamine) produced 308,000 moles of hydrogen over 60 hours of electrolysis with an applied potential of -1.25 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode.[18]

Cobalt-based photocatalysts have been reported,[19] including tris(bipyridine) cobalt(II), compounds of cobalt ligated to certain cyclic polyamines, and some cobaloximes.

In 2014 researchers announced an approach that connected a chromophore to part of a larger organic ring that surrounded a cobalt atom. The process is less efficient than a platinum catalyst although cobalt is less expensive, potentially reducing costs. The process uses one of two supramolecular assemblies based on Co(II)-templated coordination of Ru(bpy)+

32 (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridyl) analogues as photosensitizers and electron donors to a cobaloxime macrocycle. The Co(II) centers of both assemblies are high spin, in contrast to most previously described cobaloximes. Transient absorption optical spectroscopies indicate that charge recombination occurs through multiple ligand states within the photosensitizer modules.[20][21]

Bismuth vanadate

Bismuth vanadate is a visible-light-driven photocatalyst with a bandgap of 2.4 eV.[22][23] BV have demonstrated efficiencies of 5.2% for flat thin films[24][25] and 8.2% for core-shell WO3@BiVO4 nanorods with thin absorbers.[26][27][28]

Bismuth oxides

Bismuth oxides are characterized by visible light absorption properties, just like vanadates.[29][30]

Tungsten diselenide (WSe2)

Tungsten diselenide has photocatalytic properties that might be a key to more efficient electrolysis.[31]

III-V semiconductor systems

Systems based on III-V semiconductors, such as InGaP, enable solar-to-hydrogen efficiencies of up to 14%.[32] Challenges include long-term stability and cost.

2D semiconductor systems

2-dimensional semiconductors such as MoS2 are actively researched as potential photocatalysts.[33][34]

Aluminum‐based metal-organic frameworks

An aluminum‐based metal-organic framework made from 2‐aminoterephthalate can be modified by incorporating Ni2+ cations into the pores through coordination with the amino groups.[35]Molybdenum disulfide

Porous organic polymers

Organic semiconductor photocatalysts, in particular porous organic polymers (POPs), attracted attention due to their low cost, low toxicity, and tunable light absorption vs inorganic counterparts.[36][37][38] They display high porosity, low density, diverse composition, facile functionalization, high chemical/thermal stability, as well as high surface areas.[39] Efficient conversion of hydrophobic polymers into hydrophilic polymer nano-dots (Pdots) increased polymer-water interfacial contact, which significantly improved performance.[40][41][42]

Ansa-Titanocene(III/IV) Triflate Complexes

Beweries, et al., developed a light-driven "closed cycle of water splitting using ansa-titanocene(III/IV) triflate complexes".[43]

Indium gallium nitride

An Indium gallium nitride (InxGa1-xN) photocatalyst achieved a solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of 9.2% from pure water and concentrated sunlight. The effiency is due to the synergistic effects of promoting hydrogen–oxygen evolution and inhibiting recombination by operating at an optimal reaction temperature (~70 degrees C), powered by harvesting previously wasted infrared light. An STH efficiency of about 7% was realized from tap water and seawater and efficiency of 6.2% in a larger-scale system with a solar light capacity of 257 watts.[44]

Sacrificial reagents

Cd1-xZnxS

Solid solutions Cd1-xZnxS with different Zn concentration (0.2 < x < 0.35) have been investigated in the production of hydrogen from aqueous solutions containing as sacrificial reagents under visible light.[45] Textural, structural and surface catalyst properties were determined by N2 adsorption isotherms, UV–vis spectroscopy, SEM and XRD and related to the activity results in hydrogen production from water splitting under visible light. It was reported that the crystallinity and energy band structure of the Cd1-xZnxS solid solutions depend on their Zn atomic concentration. The hydrogen production rate increased gradually as Zn concentration on photocatalysts increased from 0.2 to 0.3. The subsequent increase in the Zn fraction up to 0.35 reduced production. Variation in photoactivity was analyzed for changes in crystallinity, level of the conduction band and light absorption ability of Cd1-xZnxS solid solutions derived from their Zn atomic concentration.

See also

- Artificial photosynthesis

- High-temperature electrolysis

- Photochemical reduction of carbon dioxide

- Electrolysis of water

- Photoelectrolysis of water

References

- ↑ Chu, Sheng; Li, Wei; Hamann, Thomas; Shih, Ishiang; Wang, Dunwei; Mi, Zetian (2017). "Roadmap on solar water splitting: current status and future prospects". Nano Futures 1 (2): 022001. doi:10.1088/2399-1984/aa88a1. Bibcode: 2017NanoF...1b2001C.

- ↑ Takata, Tsuyoshi; Jiang, Junzhe; Sakata, Yoshihisa; Nakabayashi, Mamiko; Shibata, Naoya; Nandal, Vikas; Seki, Kazuhiko; Hisatomi, Takashi et al. (2020-05-28). "Photocatalytic water splitting with a quantum efficiency of almost unity" (in en). Nature 581 (7809): 411–414. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2278-9. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 32461647. Bibcode: 2020Natur.581..411T. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2278-9.

- ↑ del Valle, F. et al. (Jun 2009). "Water Splitting on Semiconductor Catalysts under Visible-Light Irradiation". ChemSusChem 2 (6): 471–485. doi:10.1002/cssc.200900018. PMID 19536754.

- ↑ del Valle, F. et al. (2009). "Advances in Chemical Engineering". Photocatalytic water splitting under visible Light: concept and materials requirements. 36. pp. 111–143. doi:10.1016/S0065-2377(09)00404-9. ISBN 9780123747631.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kim, Jin Hyun; Hansora, Dharmesh; Sharma, Pankaj; Jang, Ji-Wook; Lee, Jae Sung (2019). "Toward practical solar hydrogen production – an artificial photosynthetic leaf-to-farm challenge". Chemical Society Reviews 48 (7): 1908–1971. doi:10.1039/c8cs00699g. PMID 30855624.

- ↑ Avcıoǧlu, Celal; Avcıoǧlu, Suna; Bekheet, Maged F.; Gurlo, Aleksander (13 February 2023). "Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting by SrTiO 3 : Progress Report and Design Strategies". ACS Applied Energy Materials 6 (3): 1134–1154. doi:10.1021/acsaem.2c03280.

- ↑ Yano, Junko; Yachandra, Vittal (2014-04-23). "Mn 4 Ca Cluster in Photosynthesis: Where and How Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen" (in en). Chemical Reviews 114 (8): 4175–4205. doi:10.1021/cr4004874. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 24684576.

- ↑ Gligorovski, Sasho; Strekowski, Rafal; Barbati, Stephane; Vione, Davide (2015-12-23). "Environmental Implications of Hydroxyl Radicals ( • OH)" (in en). Chemical Reviews 115 (24): 13051–13092. doi:10.1021/cr500310b. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 26630000. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr500310b.

- ↑ Fujishima, Akira (13 September 1971). "Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode". Nature 238 (5358): 37–38. doi:10.1038/238037a0. PMID 12635268. Bibcode: 1972Natur.238...37F.

- ↑ Zhou, Dantong; Li, Dongxiang; Yuan, Shengpeng; Chen, Zhi (2022-08-25). "Recent Advances in Biomass-Based Photocatalytic H 2 Production and Efficient Photocatalysts: A Review" (in en). Energy & Fuels 36 (18): 10721–10731. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c01904. ISSN 0887-0624. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c01904.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Kudo, A.; Miseki, Y. (2009). "Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting". Chem. Soc. Rev. 38 (1): 253–278. doi:10.1039/b800489g. PMID 19088977.

- ↑ Zhou, Peng; Navid, Ishtiaque Ahmed; Ma, Yongjin; Xiao, Yixin; Wang, Ping; Ye, Zhengwei; Zhou, Baowen; Sun, Kai et al. (January 2023). "Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting". Nature 613 (7942): 66–70. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05399-1. PMID 36600066. Bibcode: 2023Natur.613...66Z.

- ↑ Kato, H.; Asakura, K.; Kudo, A. (2003). "Highly Efficient Water Splitting into H and O over Lanthanum-Doped NaTaO Photocatalysts with High Crystallinity and Surface Nanostructure". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (10): 3082–3089. doi:10.1021/ja027751g. PMID 12617675.

- ↑ T. Kurihara, H. Okutomi, Y. Miseki, H. Kato, A. Kudo, "Highly Efficient Water Splitting over K3Ta3B2O12Photocatalyst without Loading Cocatalyst" Chem. Lett., 35, 274 (2006).

- ↑ K. Maeda, K. Teramura, K. Domen, "Effect of post-calcination on photocatalytic activity of (Ga1-xZnx)(N1-xOx) solid solution for overall water splitting under visible light" J. Catal., 254, 198 (2008).

- ↑ McKone, James R.; Marinescu, Smaranda C.; Brunschwig, Bruce S.; Winkler, Jay R.; Gray, Harry B. (2014). "Earth-abundant hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts" (in en). Chem. Sci. 5 (3): 865–878. doi:10.1039/C3SC51711J. ISSN 2041-6520. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C3SC51711J.

- ↑ Sutra, P.; Igau, A. (April 2018). "Emerging Earth-abundant (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu) molecular complexes for solar fuel catalysis" (in en). Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 10: 60–67. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2018.03.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2452223617300998.

- ↑ Zhang, Peili; Wang, Mei; Yang, Yong; Zheng, Dehua; Han, Kai; Sun, Licheng (2014). "Highly efficient molecular nickel catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen production from neutral water" (in en). Chem. Commun. 50 (91): 14153–14156. doi:10.1039/C4CC05511J. ISSN 1359-7345. PMID 25277377. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C4CC05511J.

- ↑ Artero, V.; Chavarot-Kerlidou, M.; Fontecave, M. (2011). "Splitting Water with Cobalt". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 50 (32): 7238–7266. doi:10.1002/anie.201007987. PMID 21748828.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Anusree; Kokhan, Oleksandr; Huang, Jier; Niklas, Jens; Chen, Lin X.; Tiede, David M.; Mulfort, Karen L. (2013). "A less-expensive way to duplicate the complicated steps of photosynthesis in making fuel". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15 (48): 21070–6. doi:10.1039/C3CP54420F. PMID 24220293. Bibcode: 2013PCCP...1521070M. http://www.kurzweilai.net/a-less-expensive-way-to-duplicate-the-complicated-steps-of-photosynthesis-in-making-fuel. Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- ↑ Mukherjee, A.; Kokhan, O.; Huang, J.; Niklas, J.; Chen, L. X.; Tiede, D. M.; Mulfort, K. L. (2013). "Detection of a charge-separated catalyst precursor state in a linked photosensitizer-catalyst assembly". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15 (48): 21070–21076. doi:10.1039/C3CP54420F. PMID 24220293. Bibcode: 2013PCCP...1521070M. https://zenodo.org/record/1230024.

- ↑ Shafiq, Iqrash; Hussain, Murid; Shehzad, Nasir; Maafa, Ibrahim M.; Akhter, Parveen; Amjad, Um-e-salma; Shafique, Sumeer; Razzaq, Abdul et al. (August 2019). "The effect of crystal facets and induced porosity on the performance of monoclinic BiVO4 for the enhanced visible-light driven photocatalytic abatement of methylene blue". Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 7 (4): 103265. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2019.103265. ISSN 2213-3437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103265.

- ↑ Shafiq, I. (2018). Mesoporous monoclinic BiVO4 for efficient visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of dyes (Doctoral dissertation, COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus.).

- ↑ Abdi, Fatwa F; Lihao Han; Arno H. M. Smets; Miro Zeman; Bernard Dam; Roel van de Krol (29 July 2013). "Efficient solar water splitting by enhanced charge separation in a bismuth vanadate-silicon tandem photoelectrode". Nature Communications 4: 2195. doi:10.1038/ncomms3195. PMID 23893238. Bibcode: 2013NatCo...4.2195A.

- ↑ Han, Lihao; Abdi, Fatwa F.; van de Krol, Roel; Liu, Rui; Huang, Zhuangqun; Lewerenz, Hans-Joachim; Dam, Bernard; Zeman, Miro et al. (2014). "Inside Cover: Efficient Water-Splitting Device Based on a Bismuth Vanadate Photoanode and Thin-Film Silicon Solar Cells (ChemSusChem 10/2014)". ChemSusChem 7 (10): 2758. doi:10.1002/cssc.201402901.

- ↑ Pihosh, Yuriy; Turkevych, Ivan; Mawatari, Kazuma; Uemura, Jin; Kazoe, Yutaka; Kosar, Sonya; Makita, Kikuo; Sugaya, Takeyoshi et al. (2015-06-08). "Photocatalytic generation of hydrogen by core-shell WO 3 /BiVO 4 nanorods with ultimate water splitting efficiency" (in en). Scientific Reports 5 (1): 11141. doi:10.1038/srep11141. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 26053164. Bibcode: 2015NatSR...511141P.

- ↑ Kosar, Sonya; Pihosh, Yuriy; Turkevych, Ivan; Mawatari, Kazuma; Uemura, Jin; Kazoe, Yutaka; Makita, Kikuo; Sugaya, Takeyoshi et al. (2016-02-25). "Tandem photovoltaic–photoelectrochemical GaAs/InGaAsP–WO3/BiVO4device for solar hydrogen generation". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 55 (4S): 04ES01. doi:10.7567/jjap.55.04es01. ISSN 0021-4922. Bibcode: 2016JaJAP..55dES01K.

- ↑ Kosar, Sonya; Pihosh, Yuriy; Bekarevich, Raman; Mitsuishi, Kazutaka; Mawatari, Kazuma; Kazoe, Yutaka; Kitamori, Takehiko; Tosa, Masahiro et al. (2019-07-01). "Highly efficient photocatalytic conversion of solar energy to hydrogen by WO3/BiVO4 core–shell heterojunction nanorods" (in en). Applied Nanoscience 9 (5): 1017–1024. doi:10.1007/s13204-018-0759-z. ISSN 2190-5517. Bibcode: 2019ApNan...9.1017K.

- ↑ Ropero-Vega, J.L.; Pedraza-Avella, J.A.; Niño-Gómez, M.E. (September 2015). "Hydrogen production by photoelectrolysis of aqueous solutions of phenol using mixed oxide semiconductor films of Bi–Nb–M–O (M=Al, Fe, Ga, In) as photoanodes" (in en). Catalysis Today 252: 150–156. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2014.11.007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920586114007512.

- ↑ Ropero-Vega, J. L.; Meléndez, A. M.; Pedraza-Avella, J. A.; Candal, Roberto J.; Niño-Gómez, M. E. (July 2014). "Mixed oxide semiconductors based on bismuth for photoelectrochemical applications" (in en). Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 18 (7): 1963–1971. doi:10.1007/s10008-014-2420-4. ISSN 1432-8488. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10008-014-2420-4.

- ↑ "Discovery Brightens Solar's Future, Energy Costs to Be Cut". NBC News from Reuters. July 2, 2015. http://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/discovery-brightens-solars-future-energy-costs-be-cut-n385841.

- ↑ May, Matthias M; Hans-Joachim Lewerenz; David Lackner; Frank Dimroth; Thomas Hannappel (15 September 2015). "Efficient direct solar-to-hydrogen conversion by in situ interface transformation of a tandem structure". Nature Communications 6: 8286. doi:10.1038/ncomms9286. PMID 26369620. Bibcode: 2015NatCo...6.8286M.

- ↑ Luo, Bin; Liu, Gang; Wang, Lianzhou (2016). "Recent advances in 2D materials for photocatalysis". Nanoscale 8 (13): 6904–6920. doi:10.1039/C6NR00546B. ISSN 2040-3364. PMID 26961514. Bibcode: 2016Nanos...8.6904L.

- ↑ Li, Yunguo; Li, Yan-Ling; Sa, Baisheng; Ahuja, Rajeev (2017). "Review of two-dimensional materials for photocatalytic water splitting from a theoretical perspective". Catalysis Science & Technology 7 (3): 545–559. doi:10.1039/C6CY02178F. ISSN 2044-4753. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1555518/.

- ↑ "Ni(2) Coordination to an Al‐Based Metal–Organic Framework Made from 2‐Aminoterephthalate for Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 56 (11): 3036–3040. February 7, 2017. doi:10.1002/anie.201612423. PMID 28170148.

- ↑ Kalsin, A. M.; Fialkowski, M.; Paszewski, M.; Smoukov, S. K.; Bishop, K. J. M.; Grzybowski, B. A. (2006-04-21). "Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Binary Nanoparticle Crystals with a Diamond-Like Lattice" (in en). Science 312 (5772): 420–424. doi:10.1126/science.1125124. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16497885. Bibcode: 2006Sci...312..420K.

- ↑ Martin, David James; Reardon, Philip James Thomas; Moniz, Savio J. A.; Tang, Junwang (2014-09-10). "Visible Light-Driven Pure Water Splitting by a Nature-Inspired Organic Semiconductor-Based System". Journal of the American Chemical Society 136 (36): 12568–12571. doi:10.1021/ja506386e. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 25136991.

- ↑ Weingarten, Adam S.; Kazantsev, Roman V.; Palmer, Liam C.; Fairfield, Daniel J.; Koltonow, Andrew R.; Stupp, Samuel I. (2015-12-09). "Supramolecular Packing Controls H2 Photocatalysis in Chromophore Amphiphile Hydrogels". Journal of the American Chemical Society 137 (48): 15241–15246. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b10027. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 26593389.

- ↑ Zhang, Ting; Xing, Guolong; Chen, Weiben; Chen, Long (2020-02-07). "Porous organic polymers: a promising platform for efficient photocatalysis" (in en). Materials Chemistry Frontiers 4 (2): 332–353. doi:10.1039/C9QM00633H. ISSN 2052-1537.

- ↑ Wang, Lei; Fernández‐Terán, Ricardo; Zhang, Lei; Fernandes, Daniel L. A.; Tian, Lei; Chen, Hong; Tian, Haining (2016). "Organic Polymer Dots as Photocatalysts for Visible Light-Driven Hydrogen Generation" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 55 (40): 12306–12310. doi:10.1002/anie.201607018. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 27604393. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/anie.201607018.

- ↑ Pati, Palas Baran; Damas, Giane; Tian, Lei; Fernandes, Daniel L. A.; Zhang, Lei; Pehlivan, Ilknur Bayrak; Edvinsson, Tomas; Araujo, C. Moyses et al. (2017-06-14). "An experimental and theoretical study of an efficient polymer nano-photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution" (in en). Energy & Environmental Science 10 (6): 1372–1376. doi:10.1039/C7EE00751E. ISSN 1754-5706.

- ↑ Rahman, Mohammad; Tian, Haining; Edvinsson, Tomas (2020). "Revisiting the Limiting Factors for Overall Water-Splitting on Organic Photocatalysts" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 59 (38): 16278–16293. doi:10.1002/anie.202002561. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 32329950.

- ↑ Godemann, Christian; Hollmann, Dirk; Kessler, Monty; Jiao, Haijun; Spannenberg, Anke; Brückner, Angelika; Beweries, Torsten (2015-12-30). "A Model of a Closed Cycle of Water Splitting Using ansa -Titanocene(III/IV) Triflate Complexes" (in en). Journal of the American Chemical Society 137 (51): 16187–16195. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b11365. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 26641723. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.5b11365.

- ↑ Zhou, Peng; Navid, Ishtiaque Ahmed; Ma, Yongjin; Xiao, Yixin; Wang, Ping; Ye, Zhengwei; Zhou, Baowen; Sun, Kai et al. (January 2023). "Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting" (in en). Nature 613 (7942): 66–70. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05399-1. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 36600066. Bibcode: 2023Natur.613...66Z. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05399-1.

- ↑ del Valle, F.; Ishikawa, A.; Domen, K.; Villoria De La Mano, J.A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.C.; González, I.D.; Herreras, S.; Mota, N. et al. (May 2009). "Influence of Zn concentration in the activity of Cd1-xZnxS solid solutions for water splitting under visible light". Catalysis Today 143 (1–2): 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2008.09.024.

|