Physics:Poisson–Boltzmann equation

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation describes the distribution of the electric potential in solution in the direction normal to a charged surface. This distribution is important to determine how the electrostatic interactions will affect the molecules in solution. The Poisson–Boltzmann equation is derived via mean-field assumptions.[1][2] From the Poisson–Boltzmann equation many other equations have been derived with a number of different assumptions.

Origins

Background and derivation

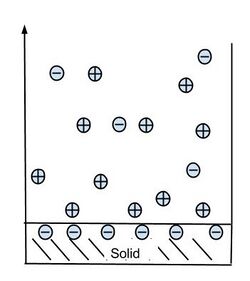

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation describes a model proposed independently by Louis Georges Gouy and David Leonard Chapman in 1910 and 1913, respectively.[3] In the Gouy-Chapman model, a charged solid comes into contact with an ionic solution, creating a layer of surface charges and counter-ions or double layer.[4] Due to thermal motion of ions, the layer of counter-ions is a diffuse layer and is more extended than a single molecular layer, as previously proposed by Hermann Helmholtz in the Helmholtz model.[3] The Stern Layer model goes a step further and takes into account the finite ion size.

| Theory | Important characteristics | Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz | Surface charge neutralized by a molecular layer of counter-ions; surface charge potential linearly dissipated from surface to counter-ions to satisfy charge[5] | Thermal motion, ion diffusion, adsorption onto the surface, solvent/surface interactions considered negligible [5] |

| Gouy-Chapman | Thermal motion of ions accounted for; ions behave as point charges[6] | Finite ion size ignored; uniformly-charged surface; non-Coulombic interactions ignored [6] |

| Stern | Finite ion size and hydration sphere considered; some ions are specifically adsorbed by the surface in the plane, known as the Stern layer[7] | Stern layer is thin compared to particle size; fluid velocity = 0 in Stern layer [7] |

The Gouy–Chapman model explains the capacitance-like qualities of the electric double layer.[4] A simple planar case with a negatively charged surface can be seen in the figure below. As expected, the concentration of counter-ions is higher near the surface than in the bulk solution.

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation describes the electrochemical potential of ions in the diffuse layer. The three-dimensional potential distribution can be described by the Poisson equation[4] where

- is the local electric charge density in C/m3,

- is the dielectric constant (relative permittivity) of the solvent,

- is the permittivity of free space,

- ψ is the electric potential.

The freedom of movement of ions in solution can be accounted for by Boltzmann statistics. The Boltzmann equation is used to calculate the local ion density such that where

- is the ion concentration at the bulk,[8]

- is the work required to move an ion closer to the surface from an infinitely far distance,

- is the Boltzmann constant,

- is the temperature in kelvins.

The equation for local ion density can be substituted into the Poisson equation under the assumptions that the work being done is only electric work, that our solution is composed of a 1:1 salt (e.g., NaCl), and that the concentration of salt is much higher than the concentration of ions.[4] The electric work to bring a charged cation or charged anion to a surface with potential ψ can be represented by and respectively.[4] These work equations can be substituted into the Boltzmann equation, producing two expressions and , where e is the charge of an electron, 1.602×10−19 coulombs.

Substituting these Boltzmann relations into the local electric charge density expression, the following expression can be obtained

Finally the charge density can be substituted into the Poisson equation to produce the Poisson–Boltzmann equation.[4]

Related theories

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation can take many forms throughout various scientific fields. In biophysics and certain surface chemistry applications, it is known simply as the Poisson–Boltzmann equation.[9] It is also known in electrochemistry as Gouy-Chapman theory; in solution chemistry as Debye–Huckel theory; in colloid chemistry as Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory.[9] Only minor modifications are necessary to apply the Poisson–Boltzmann equation to various interfacial models, making it a highly useful tool in determining electrostatic potential at surfaces.[4]

Solving analytically

Because the Poisson–Boltzmann equation is a partial differential of the second order, it is commonly solved numerically; however, with certain geometries, it can be solved analytically.

Geometries

The geometry that most easily facilitates this is a planar surface. In the case of an infinitely extended planar surface, there are two dimensions in which the potential cannot change because of symmetry. Assuming these dimensions are the y and z dimensions, only the x dimension is left. Below is the Poisson–Boltzmann equation solved analytically in terms of a second order derivative with respect to x.[4]

Analytical solutions have also been found for axial and spherical cases in a particular study.[10] The equation is in the form of a logarithm of a power series and it is as follows:

It uses a dimensionless potential and the lengths are measured in units of the Debye electron radius in the region of zero potential (where denotes the number density of negative ions in the zero potential region). For the spherical case, L=2, the axial case, L=1, and the planar case, L=0.

Low-potential vs high-potential cases

When using the Poisson–Boltzmann equation, it is important to determine if the specific case is low or high potential. The high-potential case becomes more complex so if applicable, use the low-potential equation. In the low-potential condition, the linearized version of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation (shown below) is valid, and it is commonly used as it is more simple and spans a wide variety of cases.[11]

Low-potential case conditions

Strictly, low potential means that ; however, the results that the equations yields are valid for a wider range of potentials, from 50–80mV.[4] Nevertheless, at room temperature, and that is generally the standard.[4] Some boundary conditions that apply in low potential cases are that: at the surface, the potential must be equal to the surface potential and at large distances from the surface the potential approaches a zero value. This distance decay length is yielded by the Debye length equation.[4]

As salt concentration increases, the Debye length decreases due to the ions in solution screening the surface charge.[12] A special instance of this equation is for the case of water with a monovalent salt.[4] The Debye length equation is then:

These equations all require 1:1 salt concentration cases, but if ions that have higher valence are present, the following case is used.[4]

High-potential case

The high-potential case is referred to as the “full one-dimensional case”. In order to obtain the equation, the general solution to the Poisson–Boltzmann equation is used and the case of low potentials is dropped. The equation is solved with a dimensionless parameter , which is not to be confused with the spatial coordinate symbol, y.[4] Employing several trigonometric identities and the boundary conditions that at large distances from the surface, the dimensionless potential and its derivative are zero, the high potential equation is revealed.[4]

This equation solved for is shown below.

In order to obtain a more useful equation that facilitates graphing high potential distributions, take the natural logarithm of both sides and solve for the dimensionless potential, y.

Knowing that , substitute this for y in the previous equation and solve for . The following equation is rendered.

Conditions

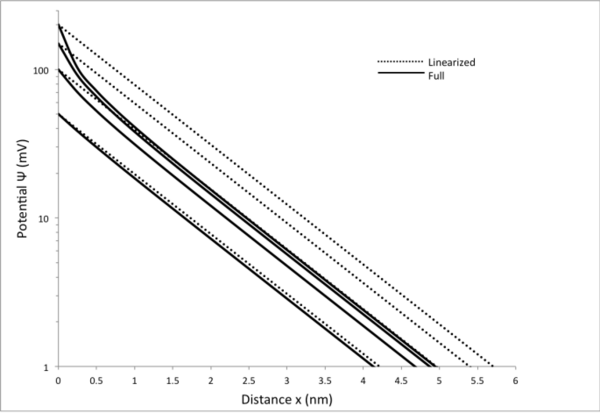

In low potential cases, the high potential equation may be used and will still yield accurate results. As the potential rises, the low potential, linear case overestimates the potential as a function of distance from the surface. This overestimation is visible at distances less than half the Debye length, where the decay is steeper than exponential decay. The following figure employs the linearized equation and the high potential graphing equation derived above. It is a potential-versus-distance graph for varying surface potentials of 50, 100, 150, and 200 mV. The equations employed in this figure assume an 80mM NaCl solution.

General applications

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation can be applied in a variety of fields mainly as a modeling tool to make approximations for applications such as charged biomolecular interactions, dynamics of electrons in semiconductors or plasma, etc. Most applications of this equation are used as models to gain further insight on electrostatics.

Physiological applications

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation can be applied to biomolecular systems. One example is the binding of electrolytes to biomolecules in a solution. This process is dependent upon the electrostatic field generated by the molecule, the electrostatic potential on the surface of the molecule, as well as the electrostatic free energy.[13]

The linearized Poisson–Boltzmann equation can be used to calculate the electrostatic potential and free energy of highly charged molecules such as tRNA in an ionic solution with different number of bound ions at varying physiological ionic strengths. It is shown that electrostatic potential depends on the charge of the molecule, while the electrostatic free energy takes into account the net charge of the system.[14]

Another example of utilizing the Poisson–Boltzmann equation is the determination of an electric potential profile at points perpendicular to the phospholipid bilayer of an erythrocyte. This takes into account both the glycocalyx and spectrin layers of the erythrocyte membrane. This information is useful for many reasons including the study of the mechanical stability of the erythrocyte membrane.[15]

Electrostatic free energy

The Poisson–Boltzmann equation can also be used to calculate the electrostatic free energy for hypothetically charging a sphere using the following charging integral: where is the final charge on the sphere

The electrostatic free energy can also be expressed by taking the process of the charging system. The following expression utilizes chemical potential of solute molecules and implements the Poisson-Boltzmann Equation with the Euler-Lagrange functional:

Note that the free energy is independent of the charging pathway [5c].

The above expression can be rewritten into separate free energy terms based on different contributions to the total free energy where

- Electrostatic fixed charges =

- Electrostatic mobile charges =

- Entropic free energy of mixing of mobile species =

- Entropic free energy of mixing of solvent =

Finally, by combining the last three term the following equation representing the outer space contribution to the free energy density integral

These equations can act as simple geometry models for biological systems such as proteins, nucleic acids, and membranes.[13] This involves the equations being solved with simple boundary conditions such as constant surface potential. These approximations are useful in fields such as colloid chemistry.[13]

Materials science

An analytical solution to the Poisson–Boltzmann equation can be used to describe an electron-electron interaction in a metal-insulator semiconductor (MIS).[16] This can be used to describe both time and position dependence of dissipative systems such as a mesoscopic system. This is done by solving the Poisson–Boltzmann equation analytically in the three-dimensional case. Solving this results in expressions of the distribution function for the Boltzmann equation and self-consistent average potential for the Poisson equation. These expressions are useful for analyzing quantum transport in a mesoscopic system. In metal-insulator semiconductor tunneling junctions, the electrons can build up close to the interface between layers and as a result the quantum transport of the system will be affected by the electron-electron interactions.[16] Certain transport properties such as electric current and electronic density can be known by solving for self-consistent Coulombic average potential from the electron-electron interactions, which is related to electronic distribution. Therefore, it is essential to analytically solve the Poisson–Boltzmann equation in order to obtain the analytical quantities in the MIS tunneling junctions.[16] Applying the following analytical solution of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation (see section 2) to MIS tunneling junctions, the following expression can be formed to express electronic transport quantities such as electronic density and electric current

Applying the equation above to the MIS tunneling junction, electronic transport can be analyzed along the z-axis, which is referenced perpendicular to the plane of the layers. An n-type junction is chosen in this case with a bias V applied along the z-axis. The self-consistent average potential of the system can be found using where

- and

λ is called the Debye length.

The electronic density and electric current can be found by manipulation to equation 16 above as functions of position z. These electronic transport quantities can be used to help understand various transport properties in the system.

Limitations [4]

As with any approximate model, the Poisson–Boltzmann equation is an approximation rather than an exact representation. Several assumptions were made to approximate the potential of the diffuse layer. The finite size of the ions was considered negligible and ions were treated as individual point charges, where ions were assumed to interact with the average electrostatic field of all their neighbors rather than each neighbor individually. In addition, non-Coulombic interactions were not considered and certain interactions were unaccounted for, such as the overlap of ion hydration spheres in an aqueous system. The permittivity of the solvent was assumed to be constant, resulting in a rough approximation as polar molecules are prevented from freely moving when they encounter the strong electric field at the solid surface.

Though the model faces certain limitations, it describes electric double layers very well. The errors resulting from the previously mentioned assumptions cancel each other for the most part. Accounting for non-Coulombic interactions increases the ion concentration at the surface and leads to a reduced surface potential. On the other hand, including the finite size of the ions causes the opposite effect. The Poisson–Boltzmann equation is most appropriate for approximating the electrostatic potential at the surface for aqueous solutions of univalent salts at concentrations smaller than 0.2 M and potentials not exceeding 50–80 mV.

In the limit of strong electrostatic interactions, a strong coupling theory is more applicable than the weak coupling assumed in deriving the Poisson-Boltzmann theory.[17]

See also

- Double layer

References

- ↑ Netz, R.R.; Orland, H. (2000-02-01). "Beyond Poisson-Boltzmann: Fluctuation effects and correlation functions" (in en). The European Physical Journal E 1 (2): 203–214. doi:10.1007/s101890050023. ISSN 1292-8941. Bibcode: 2000EPJE....1..203N.

- ↑ Attard, Phil (2002-08-07) (in en). Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics: Equilibrium by Entropy Maximisation. Academic Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-12-066321-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Aai1h6oCN74C&dq=poisson%20boltzmann%20mean-field&pg=PA318.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fogolari, F.; Brigo, A.; Molinari, H. (2002). "The Poisson–Boltzmann Equation for Biomolecular Electrostatics: a Tool for Structural Biology". J. Mol. Recognit. 15 (6): 379–385. doi:10.1002/jmr.577. PMID 12501158.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 Butt, H.; Graf, L.; Kappl, M. (2006). Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces (2nd ed.). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-40629-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 New Mexico State University. "Electric Double Layer". http://web.nmsu.edu/~snsm/classes/chem435/Lab14/double_layer.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Simon Fraser University. "Chemistry 465 Lecture 10". https://www.sfu.ca/~aroudgar/Tutorials/lecture10.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University. "The Application of a Dynamic Stern Layer Model to Electrophoretic Mobility Measurements of Latex Particles". http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/dcprieve/ELKIN/Paper44.pdf.

- ↑ "Electric Double Layer". https://web.nmsu.edu/~snsm/classes/chem435/Lab14/double_layer.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lu, B. Z. (2008). "Recent Progress in Numerical Methods for the Poisson-Boltzmann Equation in Biophysical Applications". Commun. Comput. Phys. 3 (5): 973–1009 [pp. 974–980]. https://global-sci.org/intro/article_detail/cicp/7885.html.

- ↑ D’Yachkov, L. G. (2005). "Analytical Solution of the Poisson–Boltzmann Equation in Cases of Spherical and Axial Symmetry". Technical Physics Letters 31 (3): 204–207. doi:10.1134/1.1894433. Bibcode: 2005TePhL..31..204D.

- ↑ Tuinier, R. (2003). "Approximate Solutions to the Poisson–Boltzmann Equation in Spherical and Cylindrical Geometry". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 258 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00142-X. Bibcode: 2003JCIS..258...45T.

- ↑ Sperelakis, N. (2012). Cell Physiology Sourcebook: A Molecular Approach (3rd ed.). San Diego: Acad.. ISBN 978-0-12-387738-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Fogolari, Federico; Zuccato, Pierfrancesco; Esposito, Gennaro; Viglino, Paola (1999). "Biomolecular Electrostatics with the Linearized Poisson–Boltzmann Equation". Biophysical Journal 76 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77173-0. PMID 9876118. Bibcode: 1999BpJ....76....1F.

- ↑ Gruziel, Magdalena; Grochowski, Pawel; Trylska, Joanna (2008). "The Poisson-Boltzmann model for tRNA". J. Comput. Chem. 29 (12): 1970–1981. doi:10.1002/jcc.20953. PMID 18432617.

- ↑ Cruz, Frederico A. O.; Vilhena, Fernando S. D. S.; Cortez, Celia M. (2000). "Solutions of non-linear Poisson–Boltzmann equation for erythrocyte membrane". Brazilian Journal of Physics 30 (2): 403–409. doi:10.1590/S0103-97332000000200023. Bibcode: 2000BrJPh..30..403C.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Zhang Li-Zhi; Wang Zheng-Chuan (2009). "Analytical Solution to the Boltzmann-Poisson Equation and Its Application to MIS Tunneling Junctions". Chinese Physics B 18 (2): 2975–2980. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/18/7/059. Bibcode: 2009ChPhB..18.2975Z.

- ↑ Moreira, A. G.; Netz, R. R. (2000). "Strong-coupling theory for counter-ion distributions". Europhysics Letters 52 (6): 705–711. doi:10.1209/epl/i2000-00495-1. Bibcode: 2000EL.....52..705M.

External links

- Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver – A free, open-source Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics and biomolecular solvation software package

- Zap – A Poisson–Boltzmann electrostatics solver

- MIBPB Matched Interface & Boundary based Poisson–Boltzmann solver

- CHARMM-GUI: PBEQ Solver

- AFMPB Adaptive Fast Multipole Poisson–Boltzmann Solver, free and open-source

- Global classical solutions of the Boltzmann equation with long-range interactions, Philip T. Gressman and Robert M. Strain, 2009, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Mathematics, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

|