Range query (data structures)

In data structures, a range query consists of pre-processing some input data into a data structure to efficiently answer any number of queries on any subset of the input. Particularly, there is a group of problems that have been extensively studied where the input is an array of unsorted numbers and a query consists of computing some function, such as the minimum, on a specific range of the array.

Definition

A range query [math]\displaystyle{ q_f(A,i,j) }[/math] on an array [math]\displaystyle{ A=[a_1,a_2,..,a_n] }[/math] of n elements of some set S, denoted [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,n] }[/math], takes two indices [math]\displaystyle{ 1\leq i\leq j\leq n }[/math], a function f defined over arrays of elements of S and outputs [math]\displaystyle{ f(A[i,j])= f(a_i,\ldots,a_j) }[/math].

For example, for [math]\displaystyle{ f = \sum }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,n] }[/math] an array of numbers, the range query [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i,j} A }[/math] computes [math]\displaystyle{ \sum A[i,j] = (a_i+\ldots + a_j) }[/math], for any [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i \leq j \leq n }[/math]. These queries may be answered in constant time and using [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math] extra space by calculating the sums of the first i elements of A and storing them into an auxiliary array B, such that [math]\displaystyle{ B[i] }[/math] contains the sum of the first i elements of A for every [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq i\leq n }[/math]. Therefore, any query might be answered by doing [math]\displaystyle{ \sum A[i,j] = B[j] - B[i-1] }[/math].

This strategy may be extended for every group operator f where the notion of [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1} }[/math] is well defined and easily computable.[1] Finally, this solution can be extended to two-dimensional arrays with a similar pre-processing.[2]

Examples

Semigroup operators

When the function of interest in a range query is a semigroup operator, the notion of [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1} }[/math] is not always defined, so the strategy in the previous section does not work. Andrew Yao showed[3] that there exists an efficient solution for range queries that involve semigroup operators. He proved that for any constant c, a pre-processing of time and space [math]\displaystyle{ \theta(c\cdot n) }[/math] allows to answer range queries on lists where f is a semigroup operator in [math]\displaystyle{ \theta(\alpha_c(n)) }[/math] time, where [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_c }[/math] is a certain functional inverse of the Ackermann function.

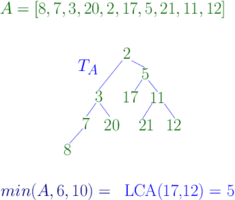

There are some semigroup operators that admit slightly better solutions. For instance when [math]\displaystyle{ f\in \{\max,\min\} }[/math]. Assume [math]\displaystyle{ f = \min }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \min(A[1..n]) }[/math] returns the index of the minimum element of [math]\displaystyle{ A[1..n] }[/math]. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \min_{i,j}(A) }[/math] denotes the corresponding minimum range query. There are several data structures that allow to answer a range minimum query in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] time using a pre-processing of time and space [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math]. One such solution is based on the equivalence between this problem and the lowest common ancestor problem.

The Cartesian tree [math]\displaystyle{ T_A }[/math] of an array [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,n] }[/math] has as root [math]\displaystyle{ a_i = \min\{a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\} }[/math] and as left and right subtrees the Cartesian tree of [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,i-1] }[/math] and the Cartesian tree of [math]\displaystyle{ A[i+1,n] }[/math] respectively. A range minimum query [math]\displaystyle{ \min_{i,j}(A) }[/math] is the lowest common ancestor in [math]\displaystyle{ T_A }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ a_j }[/math]. Because the lowest common ancestor can be solved in constant time using a pre-processing of time and space [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math], range minimum query can as well. The solution when [math]\displaystyle{ f = \max }[/math] is analogous. Cartesian trees can be constructed in linear time.

Mode

The mode of an array A is the element that appears the most in A. For instance the mode of [math]\displaystyle{ A=[4,5,6,7,4] }[/math] is 4. In case of ties any of the most frequent elements might be picked as mode. A range mode query consists in pre-processing [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,n] }[/math] such that we can find the mode in any range of [math]\displaystyle{ A[1,n] }[/math]. Several data structures have been devised to solve this problem, we summarize some of the results in the following table.[1]

| Space | Query Time | Restrictions |

|---|---|---|

| [math]\displaystyle{ O(n^{2-2\epsilon}) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ O(n^\epsilon \log n) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq \epsilon\leq \frac 1 2 }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\frac{n^2\log\log n}{\log n}\right) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] |

Recently Jørgensen et al. proved a lower bound on the cell-probe model of [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega\left(\tfrac{\log n}{\log (S w/n)}\right) }[/math] for any data structure that uses S cells.[4]

Median

This particular case is of special interest since finding the median has several applications.[5] On the other hand, the median problem, a special case of the selection problem, is solvable in O(n), using the median of medians algorithm.[6] However its generalization through range median queries is recent.[7] A range median query [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{median}(A,i,j) }[/math] where A,i and j have the usual meanings returns the median element of [math]\displaystyle{ A[i,j] }[/math]. Equivalently, [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{median}(A,i,j) }[/math] should return the element of [math]\displaystyle{ A[i,j] }[/math] of rank [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{j-i}{2} }[/math]. Range median queries cannot be solved by following any of the previous methods discussed above including Yao's approach for semigroup operators.[8]

There have been studied two variants of this problem, the offline version, where all the k queries of interest are given in a batch, and a version where all the pre-processing is done up front. The offline version can be solved with [math]\displaystyle{ O(n\log k + k \log n) }[/math] time and [math]\displaystyle{ O(n\log k) }[/math] space.

The following pseudocode of the quickselect algorithm shows how to find the element of rank r in [math]\displaystyle{ A[i,j] }[/math] an unsorted array of distinct elements, to find the range medians we set [math]\displaystyle{ r=\frac{j-i}{2} }[/math].[7]

rangeMedian(A, i, j, r) {

if A.length() == 1

return A[1]

if A.low is undefined then

m = median(A)

A.low = [e in A | e <= m]

A.high = [e in A | e > m ]

calculate t the number of elements of A[i, j] that belong to A.low

if r <= t then

return rangeMedian(A.low, i, j, r)

else

return rangeMedian(A.high, i, j, r-t)

}

Procedure rangeMedian partitions A, using A's median, into two arrays A.low and A.high, where the former contains

the elements of A that are less than or equal to the median m and the latter the rest of the elements of A. If we know that the number of elements of [math]\displaystyle{ A[i,j] }[/math] that

end up in A.low is t and this number is bigger than r then we should keep looking for the element of rank r in A.low; otherwise we should look for the element of rank [math]\displaystyle{ (r-t) }[/math] in A.high. To find t, it is enough to find the maximum index [math]\displaystyle{ m\leq i-1 }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ a_m }[/math] is in A.low and the maximum index [math]\displaystyle{ l\leq j }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ a_l }[/math]

is in A.high. Then [math]\displaystyle{ t=l-m }[/math]. The total cost for any query, without considering the partitioning part, is [math]\displaystyle{ \log n }[/math] since at most [math]\displaystyle{ \log n }[/math] recursion calls are done and only a constant number of operations are performed in each of them (to get the value of t fractional cascading should be used).

If a linear algorithm to find the medians is used, the total cost of pre-processing for k range median queries is [math]\displaystyle{ n\log k }[/math]. The algorithm can also be modified to solve the online version of the problem.[7]

Majority

Finding frequent elements in a given set of items is one of the most important tasks in data mining. Finding frequent elements might be a difficult task to achieve when most items have similar frequencies. Therefore, it might be more beneficial if some threshold of significance was used for detecting such items. One of the most famous algorithms for finding the majority of an array was proposed by Boyer and Moore [9] which is also known as the Boyer–Moore majority vote algorithm. Boyer and Moore proposed an algorithm to find the majority element of a string (if it has one) in [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math] time and using [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] space. In the context of Boyer and Moore’s work and generally speaking, a majority element in a set of items (for example string or an array) is one whose number of instances is more than half of the size of that set. Few years later, Misra and Gries [10] proposed a more general version of Boyer and Moore's algorithm using [math]\displaystyle{ O \left ( n \log \left ( \frac{1}{\tau} \right ) \right ) }[/math] comparisons to find all items in an array whose relative frequencies are greater than some threshold [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \tau\lt 1 }[/math]. A range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority query is one that, given a subrange of a data structure (for example an array) of size [math]\displaystyle{ |R| }[/math], returns the set of all distinct items that appear more than (or in some publications equal to) [math]\displaystyle{ \tau |R| }[/math] times in that given range. In different structures that support range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority queries, [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] can be either static (specified during pre-processing) or dynamic (specified at query time). Many of such approaches are based on the fact that, regardless of the size of the range, for a given [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] there could be at most [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] distinct candidates with relative frequencies at least [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]. By verifying each of these candidates in constant time, [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] query time is achieved. A range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority query is decomposable [11] in the sense that a [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority in a range [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] with partitions [math]\displaystyle{ R_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_2 }[/math] must be a [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority in either [math]\displaystyle{ R_1 }[/math]or [math]\displaystyle{ R_2 }[/math]. Due to this decomposability, some data structures answer [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority queries on one-dimensional arrays by finding the Lowest common ancestor (LCA) of the endpoints of the query range in a Range tree and validating two sets of candidates (of size [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math]) from each endpoint to the lowest common ancestor in constant time resulting in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] query time.

Two-dimensional arrays

Gagie et al.[12] proposed a data structure that supports range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority queries on an [math]\displaystyle{ m\times n }[/math] array [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. For each query [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Q}=(\operatorname{R}, \tau) }[/math] in this data structure a threshold [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \tau\lt 1 }[/math] and a rectangular range [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{R} }[/math] are specified, and the set of all elements that have relative frequencies (inside that rectangular range) greater than or equal to [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] are returned as the output. This data structure supports dynamic thresholds (specified at query time) and a pre-processing threshold [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] based on which it is constructed. During the pre-processing, a set of vertical and horizontal intervals are built on the [math]\displaystyle{ m \times n }[/math] array. Together, a vertical and a horizontal interval form a block. Each block is part of a superblock nine times bigger than itself (three times the size of the block's horizontal interval and three times the size of its vertical one). For each block a set of candidates (with [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{9}{\alpha} }[/math] elements at most) is stored which consists of elements that have relative frequencies at least [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\alpha}{9} }[/math] (the pre-processing threshold as mentioned above) in its respective superblock. These elements are stored in non-increasing order according to their frequencies and it is easy to see that, any element that has a relative frequency at least [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] in a block must appear its set of candidates. Each [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority query is first answered by finding the query block, or the biggest block that is contained in the provided query rectangle in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] time. For the obtained query block, the first [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{9}{\tau} }[/math] candidates are returned (without being verified) in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] time, so this process might return some false positives. Many other data structures (as discussed below) have proposed methods for verifying each candidate in constant time and thus maintaining the [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] query time while returning no false positives. The cases in which the query block is smaller than [math]\displaystyle{ 1/\alpha }[/math] are handled by storing [math]\displaystyle{ \log \left ( \frac{1}{\alpha} \right ) }[/math] different instances of this data structure of the following form:

[math]\displaystyle{ \beta=2^{-i}, \;\; i\in \left \{ 1,\dots,\log \left (\frac{1}{\alpha} \right ) \right \} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] is the pre-processing threshold of the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]-th instance. Thus, for query blocks smaller than [math]\displaystyle{ 1/\alpha }[/math] the [math]\displaystyle{ \lceil\log (1 / \tau)\rceil }[/math]-th instance is queried. As mentioned above, this data structure has query time [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] and requires [math]\displaystyle{ O \left ( m n(H+1) \log^2 \left ( \frac{1}{\alpha} \right ) \right ) }[/math] bits of space by storing a Huffman-encoded copy of it (note the [math]\displaystyle{ \log(\frac{1}{\alpha}) }[/math] factor and also see Huffman coding).

One-dimensional arrays

Chan et al.[13] proposed a data structure that given a one-dimensional array[math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], a subrange [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] (specified at query time) and a threshold [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] (specified at query time), is able to return the list of all [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majorities in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] time requiring [math]\displaystyle{ O(n \log n) }[/math] words of space. To answer such queries, Chan et al.[13] begin by noting that there exists a data structure capable of returning the top-k most frequent items in a range in [math]\displaystyle{ O(k) }[/math] time requiring [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math] words of space. For a one-dimensional array [math]\displaystyle{ A[0,..,n-1] }[/math], let a one-sided top-k range query to be of form [math]\displaystyle{ A[0..i] \text { for } 0 \leq i \leq n-1 }[/math]. For a maximal range of ranges [math]\displaystyle{ A[0..i] \text { through } A[0..j] }[/math] in which the frequency of a distinct element [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] remains unchanged (and equal to [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]), a horizontal line segment is constructed. The [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]-interval of this line segment corresponds to [math]\displaystyle{ [i,j] }[/math] and it has a [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math]-value equal to [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]. Since adding each element to [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] changes the frequency of exactly one distinct element, the aforementioned process creates [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math] line segments. Moreover, for a vertical line [math]\displaystyle{ x=i }[/math] all horizonal line segments intersecting it are sorted according to their frequencies. Note that, each horizontal line segment with [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]-interval [math]\displaystyle{ [\ell,r] }[/math] corresponds to exactly one distinct element [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], such that [math]\displaystyle{ A[\ell]=e }[/math]. A top-k query can then be answered by shooting a vertical ray [math]\displaystyle{ x=i }[/math] and reporting the first [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] horizontal line segments that intersect it (remember from above that these line line segments are already sorted according to their frequencies) in [math]\displaystyle{ O(k) }[/math] time.

Chan et al.[13] first construct a range tree in which each branching node stores one copy of the data structure described above for one-sided range top-k queries and each leaf represents an element from [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. The top-k data structure at each node is constructed based on the values existing in the subtrees of that node and is meant to answer one-sided range top-k queries. Please note that for a one-dimensional array [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], a range tree can be constructed by dividing [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] into two halves and recursing on both halves; therefore, each node of the resulting range tree represents a range. It can also be seen that this range tree requires [math]\displaystyle{ O(n \log n) }[/math] words of space, because there are [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log n) }[/math] levels and each level [math]\displaystyle{ \ell }[/math] has [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{\ell} }[/math] nodes. Moreover, since at each level [math]\displaystyle{ \ell }[/math] of a range tree all nodes have a total of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] elements of [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] at their subtrees and since there are [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log n) }[/math] levels, the space complexity of this range tree is [math]\displaystyle{ O(n \log n) }[/math].

Using this structure, a range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority query [math]\displaystyle{ A[i..j] }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ A[0..n-1] }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq i\leq j \leq n }[/math] is answered as follows. First, the lowest common ancestor (LCA) of leaf nodes [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] is found in constant time. Note that there exists a data structure requiring [math]\displaystyle{ O(n) }[/math] bits of space that is capable of answering the LCA queries in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] time.[14] Let [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] denote the LCA of [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math], using [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] and according to the decomposability of range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority queries (as described above and in [11]), the two-sided range query [math]\displaystyle{ A[i..j] }[/math] can be converted into two one-sided range top-k queries (from [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]). These two one-sided range top-k queries return the top-([math]\displaystyle{ 1/\tau }[/math]) most frequent elements in each of their respective ranges in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] time. These frequent elements make up the set of candidates for [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majorities in [math]\displaystyle{ A[i..j] }[/math] in which there are [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] candidates some of which might be false positives. Each candidate is then assessed in constant time using a linear-space data structure (as described in Lemma 3 in [15]) that is able to determine in [math]\displaystyle{ O(1) }[/math] time whether or not a given subrange of an array [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] contains at least [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] instances of a particular element [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math].

Tree paths

Gagie et al.[16] proposed a data structure which supports queries such that, given two nodes [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] in a tree, are able to report the list of elements that have a greater relative frequency than [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] on the path from [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math]. More formally, let [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] be a labelled tree in which each node has a label from an alphabet of size [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ label(u)\in [1,\dots,\sigma] }[/math] denote the label of node [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ P_{uv} }[/math] denote the unique path from [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] in which middle nodes are listed in the order they are visited. Given [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], and a fixed (specified during pre-processing) threshold [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \tau\lt 1 }[/math], a query [math]\displaystyle{ Q(u,v) }[/math] must return the set of all labels that appear more than [math]\displaystyle{ \tau|P_{uv}| }[/math] times in [math]\displaystyle{ P_{uv} }[/math].

To construct this data structure, first [math]\displaystyle{ {O}(\tau n) }[/math] nodes are marked. This can be done by marking any node that has distance at least [math]\displaystyle{ \lceil 1 / \tau\rceil }[/math] from the bottom of the three (height) and whose depth is divisible by [math]\displaystyle{ \lceil 1 / \tau\rceil }[/math]. After doing this, it can be observed that the distance between each node and its nearest marked ancestor is less than [math]\displaystyle{ 2\lceil 1 / \tau\rceil }[/math]. For a marked node [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \log(depth(x)) }[/math] different sequences (paths towards the root) [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math] are stored,

[math]\displaystyle{ P_{i}(x)=\left\langle \operatorname{label}(x), \operatorname{par}(x), \operatorname{par}^{2}(x), \ldots, \operatorname{par}^{2^i}(x)\right\rangle }[/math]

for [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq i \leq \log(depth(x)) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{par}(x) }[/math] returns the label of the direct parent of node [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Put another way, for each marked node, the set of all paths with a power of two length (plus one for the node itself) towards the root is stored. Moreover, for each [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math], the set of all majority candidates [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math] are stored. More specifically, [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math] contains the set of all [math]\displaystyle{ (\tau/2) }[/math]-majorities in [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math] or labels that appear more than [math]\displaystyle{ (\tau/2).(2^i+1) }[/math] times in [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math]. It is easy to see that the set of candidates [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math] can have at most [math]\displaystyle{ 2/\tau }[/math] distinct labels for each [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]. Gagie et al.[16] then note that the set of all [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majorities in the path from any marked node [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to one of its ancestors [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] is included in some [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math] (Lemma 2 in [16]) since the length of [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math] is equal to [math]\displaystyle{ (2^i+1) }[/math] thus there exists a [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq i \leq \log(depth(x)) }[/math] whose length is between [math]\displaystyle{ d_{xz} \text{ and } 2 d_{xz} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ d_{xz} }[/math] is the distance between x and z. The existence of such [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math] implies that a [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority in the path from [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] must be a [math]\displaystyle{ (\tau/2) }[/math]-majority in [math]\displaystyle{ P_i(x) }[/math], and thus must appear in [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math]. It is easy to see that this data structure require [math]\displaystyle{ O(n \log n) }[/math] words of space, because as mentioned above in the construction phase [math]\displaystyle{ O(\tau n) }[/math] nodes are marked and for each marked node some candidate sets are stored. By definition, for each marked node [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log n) }[/math] of such sets are stores, each of which contains [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] candidates. Therefore, this data structure requires [math]\displaystyle{ O(\log n \times (1/\tau) \times \tau n)=O(n \log n) }[/math] words of space. Please note that each node [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] also stores [math]\displaystyle{ count(x) }[/math] which is equal to the number of instances of [math]\displaystyle{ label(x) }[/math] on the path from [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to the root of [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math], this does not increase the space complexity since it only adds a constant number of words per node.

Each query between two nodes [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] can be answered by using the decomposability property (as explained above) of range [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majority queries and by breaking the query path between [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] into four subpaths. Let [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] be the lowest common ancestor of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math], with [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] being the nearest marked ancestors of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] respectively. The path from [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] is decomposed into the paths from [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] respectively (the size of these paths are smaller than [math]\displaystyle{ 2\lceil 1 / \tau\rceil }[/math] by definition, all of which are considered as candidates), and the paths from [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] (by finding the suitable [math]\displaystyle{ C_i(x) }[/math] as explained above and considering all of its labels as candidates). Please note that, boundary nodes have to be handled accordingly so that all of these subpaths are disjoint and from all of them a set of [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] candidates is derived. Each of these candidates is then verified using a combination of the [math]\displaystyle{ labelanc (x, \ell) }[/math] query which returns the lowest ancestor of node [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] that has label [math]\displaystyle{ \ell }[/math] and the [math]\displaystyle{ count(x) }[/math] fields of each node. On a [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math]-bit RAM and an alphabet of size [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math], the [math]\displaystyle{ labelanc (x, \ell) }[/math] query can be answered in [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\log \log _{w} \sigma\right) }[/math] time whilst having linear space requirements.[17] Therefore, verifying each of the [math]\displaystyle{ O(1/\tau) }[/math] candidates in [math]\displaystyle{ O\left(\log \log _{w} \sigma\right) }[/math] time results in [math]\displaystyle{ O\left((1/\tau)\log \log _{w} \sigma\right) }[/math] total query time for returning the set of all [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]-majorities on the path from [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math].

Related problems

All the problems described above have been studied for higher dimensions as well as their dynamic versions. On the other hand, range queries might be extended to other data structures like trees,[8] such as the level ancestor problem. A similar family of problems are orthogonal range queries, also known as counting queries.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Krizanc, Danny; Morin, Pat; Smid, Michiel H. M. (2003). "Range Mode and Range Median Queries on Lists and Trees". ISAAC: 517–526. Bibcode: 2003cs........7034K. http://cg.scs.carleton.ca/~morin/publications/.

- ↑ Meng, He; Munro, J. Ian; Nicholson, Patrick K. (2011). "Dynamic Range Selection in Linear Space". ISAAC: 160–169.

- ↑ Yao, A. C (1982). "Space-Time Tradeoff for Answering Range Queries". E 14th Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing: 128–136.

- ↑ Greve, M; J{\o}rgensen, A.; Larsen, K.; Truelsen, J. (2010). "Cell probe lower bounds and approximations for range mode". Automata, Languages and Programming: 605–616.

- ↑ Har-Peled, Sariel; Muthukrishnan, S. (2008). "Range Medians". ESA: 503–514.

- ↑ Blum, M.; Floyd, R. W.; Pratt, V. R.; Rivest, R. L.; Tarjan, R. E. (August 1973). "Time bounds for selection". Journal of Computer and System Sciences 7 (4): 448–461. doi:10.1016/S0022-0000(73)80033-9. http://people.csail.mit.edu/rivest/pubs/BFPRT73.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Beat, Gfeller; Sanders, Peter (2009). "Towards Optimal Range Medians". Icalp (1): 475–486.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bose, P; Kranakis, E.; Morin, P.; Tang, Y. (2005). "Approximate range mode and range median queries". In Proceedings of the 22nd Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science (STACS 2005), Volume 3404 of Lecture Notes in ComputerScience: 377–388. http://cg.scs.carleton.ca/~morin/publications/.

- ↑ Boyer, Robert S.; Moore, J. Strother (1991), MJRTY—A Fast Majority Vote Algorithm, Automated Reasoning Series, 1, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 105–117, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-3488-0_5, ISBN 978-94-010-5542-0, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-3488-0_5, retrieved 2021-12-18

- ↑ Misra, J.; Gries, David (November 1982). "Finding repeated elements". Science of Computer Programming 2 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1016/0167-6423(82)90012-0. ISSN 0167-6423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-6423(82)90012-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Karpiński, Marek. Searching for frequent colors in rectangles. OCLC 277046650. http://worldcat.org/oclc/277046650.

- ↑ Gagie, Travis; He, Meng; Munro, J. Ian; Nicholson, Patrick K. (2011), "Finding Frequent Elements in Compressed 2D Arrays and Strings", String Processing and Information Retrieval (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg): pp. 295–300, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24583-1_29, ISBN 978-3-642-24582-4, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24583-1_29, retrieved 2021-12-18

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Chan, Timothy M.; Durocher, Stephane; Skala, Matthew; Wilkinson, Bryan T. (2012), "Linear-Space Data Structures for Range Minority Query in Arrays", Algorithm Theory – SWAT 2012 (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg): pp. 295–306, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31155-0_26, ISBN 978-3-642-31154-3, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31155-0_26, retrieved 2021-12-20

- ↑ Sadakane, Kunihiko; Navarro, Gonzalo (2010-01-17). "Fully-Functional Succinct Trees". Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics): 134–149. doi:10.1137/1.9781611973075.13. ISBN 978-0-89871-701-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611973075.13.

- ↑ Chan, Timothy M.; Durocher, Stephane; Larsen, Kasper Green; Morrison, Jason; Wilkinson, Bryan T. (2013-03-08). "Linear-Space Data Structures for Range Mode Query in Arrays". Theory of Computing Systems 55 (4): 719–741. doi:10.1007/s00224-013-9455-2. ISSN 1432-4350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00224-013-9455-2.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Gagie, Travis; He, Meng; Navarro, Gonzalo; Ochoa, Carlos (September 2020). "Tree path majority data structures". Theoretical Computer Science 833: 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2020.05.039. ISSN 0304-3975. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tcs.2020.05.039.

- ↑ He, Meng; Munro, J. Ian; Zhou, Gelin (2014-07-08). "A Framework for Succinct Labeled Ordinal Trees over Large Alphabets". Algorithmica 70 (4): 696–717. doi:10.1007/s00453-014-9894-4. ISSN 0178-4617. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00453-014-9894-4.

External links

- Open Data Structure - Chapter 13 - Data Structures for Integers

- Data Structures for Range Median Queries - Gerth Stolting Brodal and Allan Gronlund Jorgensen