Binary search tree

| Binary search tree | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | tree | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented | 1960 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented by | P.F. Windley, A.D. Booth, A.J.T. Colin, and T.N. Hibbard | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Time complexity in big O notation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

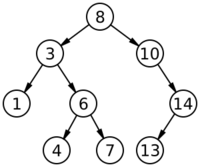

In computer science, a binary search tree (BST), also called an ordered or sorted binary tree, is a rooted binary tree data structure with the key of each internal node being greater than all the keys in the respective node's left subtree and less than the ones in its right subtree. The time complexity of operations on the binary search tree is linear with respect to the height of the tree.

Binary search trees allow binary search for fast lookup, addition, and removal of data items. Since the nodes in a BST are laid out so that each comparison skips about half of the remaining tree, the lookup performance is proportional to that of binary logarithm. BSTs were devised in the 1960s for the problem of efficient storage of labeled data and are attributed to Conway Berners-Lee and David Wheeler.

The performance of a binary search tree is dependent on the order of insertion of the nodes into the tree since arbitrary insertions may lead to degeneracy; several variations of the binary search tree can be built with guaranteed worst-case performance. The basic operations include: search, traversal, insert and delete. BSTs with guaranteed worst-case complexities perform better than an unsorted array, which would require linear search time.

The complexity analysis of BST shows that, on average, the insert, delete and search takes for nodes. In the worst case, they degrade to that of a singly linked list: . To address the boundless increase of the tree height with arbitrary insertions and deletions, self-balancing variants of BSTs are introduced to bound the worst lookup complexity to that of the binary logarithm. AVL trees were the first self-balancing binary search trees, invented in 1962 by Georgy Adelson-Velsky and Evgenii Landis.[1][2][3]

Binary search trees can be used to implement abstract data types such as dynamic sets, lookup tables and priority queues, and used in sorting algorithms such as tree sort.

History

The binary search tree algorithm was discovered independently by several researchers, including P.F. Windley, Andrew Donald Booth, Andrew Colin, Thomas N. Hibbard.[4][5] The algorithm is attributed to Conway Berners-Lee and David Wheeler, who used it for storing labeled data in magnetic tapes in 1960.[6] One of the earliest and popular binary search tree algorithm is that of Hibbard.[4]

The time complexity of a binary search tree increases boundlessly with the tree height if the nodes are inserted in an arbitrary order, therefore self-balancing binary search trees were introduced to bound the height of the tree to .[7] Various height-balanced binary search trees were introduced to confine the tree height, such as AVL trees, Treaps, and red–black trees.[8]

Overview

A binary search tree is a rooted binary tree in which nodes are arranged in strict total order in which the nodes with keys greater than any particular node A is stored on the right sub-trees to that node A and the nodes with keys equal to or less than A are stored on the left sub-trees to A, satisfying the binary search property.[9]: 298 [10]: 287

Binary search trees are also efficacious in sortings and search algorithms. However, the search complexity of a BST depends upon the order in which the nodes are inserted and deleted; since in worst case, successive operations in the binary search tree may lead to degeneracy and form a singly linked list (or "unbalanced tree") like structure, thus has the same worst-case complexity as a linked list.[11][9]: 299-302

Binary search trees are also a fundamental data structure used in construction of abstract data structures such as sets, multisets, and associative arrays.

Operations

Searching

Searching in a binary search tree for a specific key can be programmed recursively or iteratively.

Searching begins by examining the root node. If the tree is nil, the key being searched for does not exist in the tree. Otherwise, if the key equals that of the root, the search is successful and the node is returned. If the key is less than that of the root, the search proceeds by examining the left subtree. Similarly, if the key is greater than that of the root, the search proceeds by examining the right subtree. This process is repeated until the key is found or the remaining subtree is . If the searched key is not found after a subtree is reached, then the key is not present in the tree.[10]: 290–291

Recursive search

The following pseudocode implements the BST search procedure through recursion.[10]: 290

Recursive-Tree-Search(x, key)

if x = NIL or key = x.key then

return x

if key < x.key then

return Recursive-Tree-Search(x.left, key)

else

return Recursive-Tree-Search(x.right, key)

end if

|

The recursive procedure continues until a or the being searched for are encountered.

Iterative search

The recursive version of the search can be "unrolled" into a while loop. On most machines, the iterative version is found to be more efficient.[10]: 291

Iterative-Tree-Search(x, key)

while x ≠ NIL and key ≠ x.key do

if key < x.key then

x := x.left

else

x := x.right

end if

repeat

return x

|

Since the search may proceed till some leaf node, the running time complexity of BST search is where is the height of the tree. However, the worst case for BST search is where is the total number of nodes in the BST, because an unbalanced BST may degenerate to a linked list. However, if the BST is height-balanced the height is .[10]: 290

Successor and predecessor

For certain operations, given a node , finding the successor or predecessor of is crucial. Assuming all the keys of a BST are distinct, the successor of a node in a BST is the node with the smallest key greater than 's key. On the other hand, the predecessor of a node in a BST is the node with the largest key smaller than 's key. The following pseudocode finds the successor and predecessor of a node in a BST.[12][13][10]: 292–293

BST-Successor(x)

if x.right ≠ NIL then

return BST-Minimum(x.right)

end if

y := x.parent

while y ≠ NIL and x = y.right do

x := y

y := y.parent

repeat

return y

|

BST-Predecessor(x)

if x.left ≠ NIL then

return BST-Maximum(x.left)

end if

y := x.parent

while y ≠ NIL and x = y.left do

x := y

y := y.parent

repeat

return y

|

Operations such as finding a node in a BST whose key is the maximum or minimum are critical in certain operations, such as determining the successor and predecessor of nodes. Following is the pseudocode for the operations.[10]: 291–292

BST-Maximum(x)

while x.right ≠ NIL do

x := x.right

repeat

return x

|

BST-Minimum(x)

while x.left ≠ NIL do

x := x.left

repeat

return x

|

Insertion

Operations such as insertion and deletion cause the BST representation to change dynamically. The data structure must be modified in such a way that the properties of BST continue to hold. New nodes are inserted as leaf nodes in the BST.[10]: 294–295 Following is an iterative implementation of the insertion operation.[10]: 294

1 BST-Insert(T, z) 2 y := NIL 3 x := T.root 4 while x ≠ NIL do 5 y := x 6 if z.key < x.key then 7 x := x.left 8 else 9 x := x.right 10 end if 11 repeat 12 z.parent := y 13 if y = NIL then 14 T.root := z 15 else if z.key < y.key then 16 y.left := z 17 else 18 y.right := z 19 end if |

The procedure maintains a "trailing pointer" as a parent of . After initialization on line 2, the while loop along lines 4-11 causes the pointers to be updated. If is , the BST is empty, thus is inserted as the root node of the binary search tree , if it is not , insertion proceeds by comparing the keys to that of on the lines 15-19 and the node is inserted accordingly.[10]: 295

Deletion

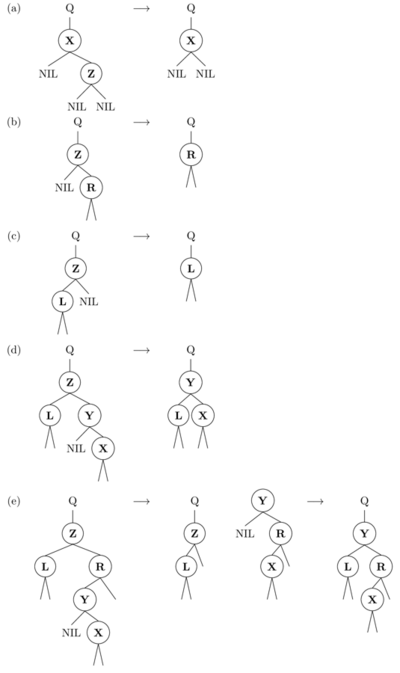

The deletion of a node, say , from the binary search tree has three cases:[10]: 295-297

- If is a leaf node, it is replaced by as shown in (a).

- If has only one child, the child node of gets elevated by modifying the parent node of to point to the child node, consequently taking 's position in the tree, as shown in (b) and (c).

- If has both left and right children, the in-order successor of , say , displaces by following the two cases:

- If is 's right child, as shown in (d), displaces and 's right child remain unchanged.

- If lies within 's right subtree but is not 's right child, as shown in (e), first gets replaced by its own right child, and then it displaces 's position in the tree.

- Alternatively, the in-order predecessor can also be used.

The following pseudocode implements the deletion operation in a binary search tree.[10]: 296-298

1 BST-Delete(BST, z) 2 if z.left = NIL then 3 Shift-Nodes(BST, z, z.right) 4 else if z.right = NIL then 5 Shift-Nodes(BST, z, z.left) 6 else 7 y := BST-Successor(z) 8 if y.parent ≠ z then 9 Shift-Nodes(BST, y, y.right) 10 y.right := z.right 11 y.right.parent := y 12 end if 13 Shift-Nodes(BST, z, y) 14 y.left := z.left 15 y.left.parent := y 16 end if |

1 Shift-Nodes(BST, u, v) 2 if u.parent = NIL then 3 BST.root := v 4 else if u = u.parent.left then 5 u.parent.left := v 5 else 6 u.parent.right := v 7 end if 8 if v ≠ NIL then 9 v.parent := u.parent 10 end if |

The procedure deals with the 3 special cases mentioned above. Lines 2-3 deal with case 1; lines 4-5 deal with case 2 and lines 6-16 for case 3. The helper function is used within the deletion algorithm for the purpose of replacing the node with in the binary search tree .[10]: 298 This procedure handles the deletion (and substitution) of from .

Traversal

A BST can be traversed through three basic algorithms: inorder, preorder, and postorder tree walks.[10]: 287

- Inorder tree walk: Nodes from the left subtree get visited first, followed by the root node and right subtree. Such a traversal visits all the nodes in the order of non-decreasing key sequence.

- Preorder tree walk: The root node gets visited first, followed by left and right subtrees.

- Postorder tree walk: Nodes from the left subtree get visited first, followed by the right subtree, and finally, the root.

Following is a recursive implementation of the tree walks.[10]: 287–289

Inorder-Tree-Walk(x)

if x ≠ NIL then

Inorder-Tree-Walk(x.left)

visit node

Inorder-Tree-Walk(x.right)

end if

|

Preorder-Tree-Walk(x)

if x ≠ NIL then

visit node

Preorder-Tree-Walk(x.left)

Preorder-Tree-Walk(x.right)

end if

|

Postorder-Tree-Walk(x)

if x ≠ NIL then

Postorder-Tree-Walk(x.left)

Postorder-Tree-Walk(x.right)

visit node

end if

|

Balanced binary search trees

Without rebalancing, insertions or deletions in a binary search tree may lead to degeneration, resulting in a height of the tree (where is number of items in a tree), so that the lookup performance is deteriorated to that of a linear search.[14] Keeping the search tree balanced and height bounded by is a key to the usefulness of the binary search tree. This can be achieved by "self-balancing" mechanisms during the updation operations to the tree designed to maintain the tree height to the binary logarithmic complexity.[7][15]: 50

Height-balanced trees

A tree is height-balanced if the heights of the left sub-tree and right sub-tree are guaranteed to be related by a constant factor. This property was introduced by the AVL tree and continued by the red–black tree.[15]: 50–51 The heights of all the nodes on the path from the root to the modified leaf node have to be observed and possibly corrected on every insert and delete operation to the tree.[15]: 52

Weight-balanced trees

In a weight-balanced tree, the criterion of a balanced tree is the number of leaves of the subtrees. The weights of the left and right subtrees differ at most by .[16][15]: 61 However, the difference is bound by a ratio of the weights, since a strong balance condition of cannot be maintained with rebalancing work during insert and delete operations. The -weight-balanced trees gives an entire family of balance conditions, where each left and right subtrees have each at least a fraction of of the total weight of the subtree.[15]: 62

Types

There are several self-balanced binary search trees, including T-tree,[17] treap,[18] red-black tree,[19] B-tree,[20] 2–3 tree,[21] and Splay tree.[22]

Examples of applications

Sort

Binary search trees are used in sorting algorithms such as tree sort, where all the elements are inserted at once and the tree is traversed at an in-order fashion.[23] BSTs are also used in quicksort.[24]

Priority queue operations

Binary search trees are used in implementing priority queues, using the node's key as priorities. Adding new elements to the queue follows the regular BST insertion operation but the removal operation depends on the type of priority queue:[25]

- If it is an ascending order priority queue, removal of an element with the lowest priority is done through leftward traversal of the BST.

- If it is a descending order priority queue, removal of an element with the highest priority is done through rightward traversal of the BST.

See also

References

- ↑ Pitassi, Toniann (2015). "CSC263: Balanced BSTs, AVL tree". University of Toronto, Department of Computer Science. p. 6. http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~toni/Courses/263-2015/lectures/lec04-balanced-augmentation.pdf.

- ↑ Myers, Andrew. "CS 312 Lecture: AVL Trees". Cornell University, Department of Computer Science. https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs312/2008sp/lectures/lec_avl.html.

- ↑ Adelson-Velsky, Georgy; Landis, Evgenii (1962). "An algorithm for the organization of information" (in ru). Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences 146: 263–266. English translation by Myron J. Ricci in Soviet Mathematics - Doklady, 3:1259–1263, 1962.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Culberson, J.; Munro, J. I. (1 January 1989). "Explaining the Behaviour of Binary Search Trees Under Prolonged Updates: A Model and Simulations". The Computer Journal 32 (1): 68–69. doi:10.1093/comjnl/32.1.68. https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article/32/1/68/341965?login=true.

- ↑ Culberson, J.; Munro, J. I. (28 July 1986). "Analysis of the standard deletion algorithms in exact fit domain binary search trees". Algorithmica (Springer Publishing, University of Waterloo) 5 (1–4): 297. doi:10.1007/BF01840390. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF01840390.

- ↑ P. F. Windley (1 January 1960). "Trees, Forests and Rearranging". The Computer Journal 3 (2): 84. doi:10.1093/comjnl/3.2.84. https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article/3/2/84/504799.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Knuth, Donald (1998). "Section 6.2.3: Balanced Trees". The Art of Computer Programming. 3 (2 ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 458–481. ISBN 978-0201896855. https://ia801604.us.archive.org/17/items/B-001-001-250/B-001-001-250.pdf.

- ↑ Paul E. Black, "red-black tree", in Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures [online], Paul E. Black, ed. 12 November 2019. (accessed May 19 2022) from: https://www.nist.gov/dads/HTML/redblack.html

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Thareja, Reema (13 October 2018). "Hashing and Collision". Data Structures Using C (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198099307. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/data-structures-using-c-9780198099307.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/introduction-algorithms-second-edition.

- ↑ R. A. Frost; M. M. Peterson (1 February 1982). "A Short Note on Binary Search Trees". The Computer Journal (Oxford University Press) 25 (1): 158. doi:10.1093/comjnl/25.1.158. https://academic.oup.com/comjnl/article/25/1/158/527326.

- ↑ Junzhou Huang. "Design and Analysis of Algorithms". University of Texas at Arlington. p. 12. https://ranger.uta.edu/~huang/teaching/CSE5311/CSE5311_Lecture10.pdf.

- ↑ Ray, Ray. "Binary Search Tree". Loyola Marymount University, Department of Computer Science. https://cs.lmu.edu/~ray/notes/binarysearchtrees/.

- ↑ Thornton, Alex (2021). "ICS 46: Binary Search Trees". University of California, Irvine. https://www.ics.uci.edu/~thornton/ics46/Notes/BinarySearchTrees/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Brass, Peter (January 2011). Advanced Data Structure. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511800191. ISBN 9780511800191. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/advanced-data-structures/D56E2269D7CEE969A3B8105AD5B9254C.

- ↑ Blum, Norbert; Mehlhorn, Kurt (1978). "On the Average Number of Rebalancing Operations in Weight-Balanced Trees". Theoretical Computer Science 11 (3): 303–320. doi:10.1016/0304-3975(80)90018-3. http://scidok.sulb.uni-saarland.de/volltexte/2011/4019/pdf/fb14_1978_06.pdf.

- ↑ Lehman, Tobin J.; Carey, Michael J. (25–28 August 1986). "A Study of Index Structures for Main Memory Database Management Systems". Twelfth International Conference on Very Large Databases (VLDB 1986). Kyoto. ISBN 0-934613-18-4. https://archive.org/details/verylargedatabas0000inte.

- ↑ Aragon, Cecilia R.; Seidel, Raimund (1989), "Randomized Search Trees", 30th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Washington, D.C.: IEEE Computer Society Press, pp. 540–545, doi:10.1109/SFCS.1989.63531, ISBN 0-8186-1982-1, http://faculty.washington.edu/aragon/pubs/rst89.pdf

- ↑ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). "Red–Black Trees". Introduction to Algorithms (second ed.). MIT Press. pp. 273–301. ISBN 978-0-262-03293-3.

- ↑ Comer, Douglas (June 1979), "The Ubiquitous B-Tree", Computing Surveys 11 (2): 123–137, doi:10.1145/356770.356776, ISSN 0360-0300

- ↑ Knuth, Donald M (1998). "6.2.4". The Art of Computer Programming. 3 (2 ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 9780201896855. "The 2–3 trees defined at the close of Section 6.2.3 are equivalent to B-Trees of order 3."

- ↑ Sleator, Daniel D.; Tarjan, Robert E. (1985). "Self-Adjusting Binary Search Trees". Journal of the ACM 32 (3): 652–686. doi:10.1145/3828.3835. https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~sleator/papers/self-adjusting.pdf.

- ↑ Narayanan, Arvind (2019). "COS226: Binary search trees". Princeton University School of Engineering and Applied Science. https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/spring19/cos226/lectures/study/32BinarySearchTrees.html.

- ↑ Xiong, Li. "A Connection Between Binary Search Trees and Quicksort". Oxford College of Emory University, The Department of Mathematics and Computer Science. http://mathcenter.oxford.emory.edu/site/cs171/bstQuicksortConnection/.

- ↑ Myers, Andrew. "CS 2112 Lecture and Recitation Notes: Priority Queues and Heaps". Cornell University, Department of Computer Science. https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs4120/2016sp/lectures/lec_heaps/.

Further reading

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E.. "Binary Search Tree". https://xlinux.nist.gov/dads/HTML/binarySearchTree.html.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E.. "Binary Search Tree". https://xlinux.nist.gov/dads/HTML/binarySearchTree.html.- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). "12: Binary search trees, 15.5: Optimal binary search trees". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press. pp. 253–272, 356–363. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/introduction-algorithms-second-edition.

- Jarc, Duane J. (3 December 2005). "Binary Tree Traversals". Interactive Data Structure Visualizations. University of Maryland. http://nova.umuc.edu/~jarc/idsv/lesson1.html.

- Knuth, Donald (1997). "6.2.2: Binary Tree Searching". The Art of Computer Programming. 3: "Sorting and Searching" (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 426–458. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.

- Long, Sean. "Binary Search Tree" (PPT). Data Structures and Algorithms Visualization-A PowerPoint Slides Based Approach. SUNY Oneonta. http://employees.oneonta.edu/zhangs/PowerPointPlatform/resources/samples/binarysearchtree.ppt.

- Parlante, Nick (2001). "Binary Trees". CS Education Library. Stanford University. http://cslibrary.stanford.edu/110/BinaryTrees.html.

External links

- Ben Pfaff: An Introduction to Binary Search Trees and Balanced Trees. (PDF; 1675 kB) 2004.

- Binary Tree Visualizer (JavaScript animation of various BT-based data structures)

|