Rational function

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In mathematics, a rational function is any function that can be defined by a rational fraction, which is an algebraic fraction such that both the numerator and the denominator are polynomials. The coefficients of the polynomials need not be rational numbers; they may be taken in any field K. In this case, one speaks of a rational function and a rational fraction over K. The values of the variables may be taken in any field L containing K. Then the domain of the function is the set of the values of the variables for which the denominator is not zero, and the codomain is L.

The set of rational functions over a field K is a field, the field of fractions of the ring of the polynomial functions over K.

Definitions

A function is called a rational function if it can be written in the form[1]

where and are polynomial functions of and is not the zero function. The domain of is the set of all values of for which the denominator is not zero.

However, if and have a non-constant polynomial greatest common divisor , then setting and produces a rational function

which may have a larger domain than , and is equal to on the domain of It is a common usage to identify and , that is to extend "by continuity" the domain of to that of Indeed, one can define a rational fraction as an equivalence class of fractions of polynomials, where two fractions and are considered equivalent if . In this case is equivalent to

A proper rational function is a rational function in which the degree of is less than the degree of and both are real polynomials, named by analogy to a proper fraction in [2]

Complex rational functions

In complex analysis, a rational function

is the ratio of two polynomials with complex coefficients, where Q is not the zero polynomial and P and Q have no common factor (this avoids f taking the indeterminate value 0/0).

The domain of f is the set of complex numbers such that . Every rational function can be naturally extended to a function whose domain and range are the whole Riemann sphere, i.e., a rational mapping. Iteration of rational functions on the Riemann sphere forms a discrete dynamical system.[3]

A complex rational function with degree one is a Möbius transformation.

Rational functions are representative examples of meromorphic functions.[4]

- Julia sets for rational maps

-

-

Degree

There are several non equivalent definitions of the degree of a rational function.

Most commonly, the degree of a rational function is the maximum of the degrees of its constituent polynomials P and Q, when the fraction is reduced to lowest terms. If the degree of f is d, then the equation

has d distinct solutions in z except for certain values of w, called critical values, where two or more solutions coincide or where some solution is rejected at infinity (that is, when the degree of the equation decreases after having cleared the denominator).

The degree of the graph of a rational function is not the degree as defined above: it is the maximum of the degree of the numerator and one plus the degree of the denominator.

In some contexts, such as in asymptotic analysis, the degree of a rational function is the difference between the degrees of the numerator and the denominator.[5]: §13.6.1 [6]: Chapter IV

In network synthesis and network analysis, a rational function of degree two (that is, the ratio of two polynomials of degree at most two) is often called a biquadratic function.[7]

Examples

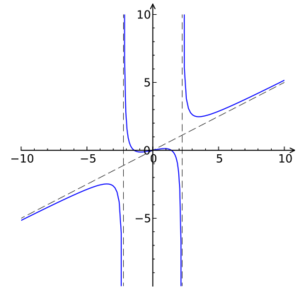

The rational function

is not defined at

It is asymptotic to as

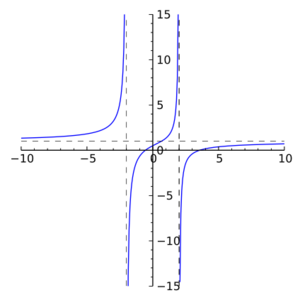

The rational function

is defined for all real numbers, but not for all complex numbers, since if x were a square root of (i.e. the imaginary unit or its negative), then formal evaluation would lead to division by zero:

which is undefined.

A constant function such as f(x) = π is a rational function since constants are polynomials. The function itself is rational, even though the value of f(x) is irrational for all x.

Every polynomial function is a rational function with A function that cannot be written in this form, such as is not a rational function. However, the adjective "irrational" is not generally used for functions.

Every Laurent polynomial can be written as a rational function while the converse is not necessarily true, i.e., the ring of Laurent polynomials is a subring of the rational functions.

The rational function is equal to 1 for all x except 0, where there is a removable singularity. The sum, product, or quotient (excepting division by the zero polynomial) of two rational functions is itself a rational function. However, the process of reduction to standard form may inadvertently result in the removal of such singularities unless care is taken. Using the definition of rational functions as equivalence classes gets around this, since x/x is equivalent to 1/1.

Taylor series

The coefficients of a Taylor series of any rational function satisfy a linear recurrence relation, which can be found by equating the rational function to a Taylor series with indeterminate coefficients, and collecting like terms after clearing the denominator.

For example,

Multiplying through by the denominator and distributing,

After adjusting the indices of the sums to get the same powers of x, we get

Combining like terms gives

Since this holds true for all x in the radius of convergence of the original Taylor series, we can compute as follows. Since the constant term on the left must equal the constant term on the right it follows that

Then, since there are no powers of x on the left, all of the coefficients on the right must be zero, from which it follows that

Conversely, any sequence that satisfies a linear recurrence determines a rational function when used as the coefficients of a Taylor series. This is useful in solving such recurrences, since by using partial fraction decomposition we can write any proper rational function as a sum of factors of the form 1 / (ax + b) and expand these as geometric series, giving an explicit formula for the Taylor coefficients; this is the method of generating functions.

Abstract algebra

In abstract algebra the concept of a polynomial is extended to include formal expressions in which the coefficients of the polynomial can be taken from any field. In this setting, given a field F and some indeterminate X, a rational expression (also known as a rational fraction or, in algebraic geometry, a rational function) is any element of the field of fractions of the polynomial ring F[X]. Any rational expression can be written as the quotient of two polynomials P/Q with Q ≠ 0, although this representation isn't unique. P/Q is equivalent to R/S, for polynomials P, Q, R, and S, when PS = QR. However, since F[X] is a unique factorization domain, there is a unique representation for any rational expression P/Q with P and Q polynomials of lowest degree and Q chosen to be monic. This is similar to how a fraction of integers can always be written uniquely in lowest terms by canceling out common factors.

The field of rational expressions is denoted F(X). This field is said to be generated (as a field) over F by (a transcendental element) X, because F(X) does not contain any proper subfield containing both F and the element X.

Notion of a rational function on an algebraic variety

Like polynomials, rational expressions can also be generalized to n indeterminates X1,..., Xn, by taking the field of fractions of F[X1,..., Xn], which is denoted by F(X1,..., Xn).

An extended version of the abstract idea of rational function is used in algebraic geometry. There the function field of an algebraic variety V is formed as the field of fractions of the coordinate ring of V (more accurately said, of a Zariski-dense affine open set in V). Its elements f are considered as regular functions in the sense of algebraic geometry on non-empty open sets U, and also may be seen as morphisms to the projective line.

Applications

Rational functions are used in numerical analysis for interpolation and approximation of functions, for example the Padé approximants introduced by Henri Padé. Approximations in terms of rational functions are well suited for computer algebra systems and other numerical software. Like polynomials, they can be evaluated straightforwardly, and at the same time they express more diverse behavior than polynomials.

In signal processing, the Laplace transform (for continuous systems) or the z-transform (for discrete-time systems) of the impulse response of commonly used linear time-invariant systems (filters) with infinite impulse response are rational functions over complex numbers.

See also

- Partial fraction decomposition

- Partial fractions in integration

- Function field of an algebraic variety

- Algebraic fractions – a generalization of rational functions that allows taking integer roots

References

- ↑ Rudin, Walter (1987). Real and Complex Analysis. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-07-100276-9.

- ↑

- Corless, Martin J.; Frazho, Art (2003). Linear Systems and Control. CRC Press. p. 163. ISBN 0203911377.

- Pownall, Malcolm W. (1983). Functions and Graphs: Calculus Preparatory Mathematics. Prentice-Hall. p. 203. ISBN 0133323048.

- ↑ Blanchard, Paul (1984). "Complex analytic dynamics on the Riemann sphere". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 11 (1): 85–141. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1984-15240-6. ISSN 0273-0979. https://projecteuclid.org/journals/bulletin-of-the-american-mathematical-society-new-series/volume-11/issue-1/Complex-analytic-dynamics-on-the-Riemann-sphere/bams/1183551835.full. p. 87

- ↑ Ablowitz, Mark J.; Fokas, Athanassios S. (2003). Complex Variables. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-53429-1.

- ↑ Bourles, Henri (2010). Linear Systems. Wiley. p. 515. doi:10.1002/9781118619988. ISBN 978-1-84821-162-9. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118619988. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑ Bourbaki, N. (1990). Algebra II. Springer. p. A.IV.20. ISBN 3-540-19375-8.

- ↑ Glisson, Tildon H. (2011). Introduction to Circuit Analysis and Design. Springer. ISBN 978-9048194438.

Further reading

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Rational function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Rational_function&oldid=17805

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. (2007), "Section 3.4. Rational Function Interpolation and Extrapolation", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8, http://nrbook.com/book.html

External links

|