Rectangular function

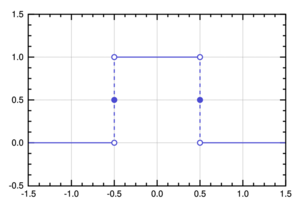

The rectangular function (also known as the rectangle function, rect function, Pi function, Heaviside Pi function,[1] gate function, unit pulse, or the normalized boxcar function) is defined as[2]

Alternative definitions of the function define to be 0,[3] 1,[4][5] or undefined.

Its periodic version is called a rectangular wave.

History

The rect function has been introduced by Woodward[6] in [7] as an ideal cutout operator, together with the sinc function[8][9] as an ideal interpolation operator, and their counter operations which are sampling (comb operator) and replicating (rep operator), respectively.

Relation to the boxcar function

The rectangular function is a special case of the more general boxcar function:

where is the Heaviside step function; the function is centered at and has duration , from to

Fourier transform of the rectangular function

The unitary Fourier transforms of the rectangular function are[2] using ordinary frequency f, where is the normalized form[10] of the sinc function and using angular frequency , where is the unnormalized form of the sinc function.

For , its Fourier transform isNote that as long as the definition of the pulse function is only motivated by its behavior in the time-domain experience, there is no reason to believe that the oscillatory interpretation (i.e. the Fourier transform function) should be intuitive, or directly understood by humans. However, some aspects of the theoretical result may be understood intuitively, as finiteness in time domain corresponds to an infinite frequency response. (Vice versa, a finite Fourier transform will correspond to infinite time domain response.)

Relation to the triangular function

We can define the triangular function as the convolution of two rectangular functions:

Use in probability

Viewing the rectangular function as a probability density function, it is a special case of the continuous uniform distribution with The characteristic function is

and its moment-generating function is

where is the hyperbolic sine function.

Rational approximation

The pulse function may also be expressed as a limit of a rational function:

Demonstration of validity

First, we consider the case where Notice that the term is always positive for integer However, and hence approaches zero for large

It follows that:

Second, we consider the case where Notice that the term is always positive for integer However, and hence grows very large for large

It follows that:

Third, we consider the case where We may simply substitute in our equation:

We see that it satisfies the definition of the pulse function. Therefore,

Dirac delta function

The rectangle function can be used to represent the Dirac delta function .[11] Specifically,For a function , its average over the width around 0 in the function domain is calculated as,

To obtain , the following limit is applied,

and this can be written in terms of the Dirac delta function as, The Fourier transform of the Dirac delta function is

where the sinc function here is the normalized sinc function. Because the first zero of the sinc function is at and goes to infinity, the Fourier transform of is

means that the frequency spectrum of the Dirac delta function is infinitely broad. As a pulse is shorten in time, it is larger in spectrum.

See also

References

- ↑ Wolfram Research (2008). "HeavisidePi, Wolfram Language function". https://reference.wolfram.com/language/ref/HeavisidePi.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weisstein, Eric W.. "Rectangle Function". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/RectangleFunction.html.

- ↑ Wang, Ruye (2012). Introduction to Orthogonal Transforms: With Applications in Data Processing and Analysis. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9780521516884. https://books.google.com/books?id=4KEKGjaiJn0C&pg=PA135.

- ↑ Tang, K. T. (2007). Mathematical Methods for Engineers and Scientists: Fourier analysis, partial differential equations and variational models. Springer. p. 85. ISBN 9783540446958. https://books.google.com/books?id=gG-ybR3uIGsC&pg=PA85.

- ↑ Kumar, A. Anand (2011). Signals and Systems. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.. pp. 258–260. ISBN 9788120343108. https://books.google.com/books?id=FGGa6BXhy3kC&pg=PA258.

- ↑ Klauder, John R (1960). "The Theory and Design of Chirp Radars". Bell System Technical Journal 39 (4): 745–808. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1960.tb03942.x. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6773600.

- ↑ Woodward, Philipp M (1953). Probability and Information Theory, with Applications to Radar. Pergamon Press. pp. 29.

- ↑ Higgins, John Rowland (1996). Sampling Theory in Fourier and Signal Analysis: Foundations. Oxford University Press Inc.. pp. 4. ISBN 0198596995.

- ↑ Zayed, Ahmed I (1996). Handbook of Function and Generalized Function Transformations. CRC Press. pp. 507. ISBN 9780849380761.

- ↑ Wolfram MathWorld, https://mathworld.wolfram.com/SincFunction.html

- ↑ Khare, Kedar; Butola, Mansi; Rajora, Sunaina (2023). "Chapter 2.4 Sampling by Averaging, Distributions and Delta Function". Fourier Optics and Computational Imaging (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 15-16. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-18353-9. ISBN 978-3-031-18353-9.

|