Social:Pe̍h-ōe-jī

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī Church Romanization | |

|---|---|

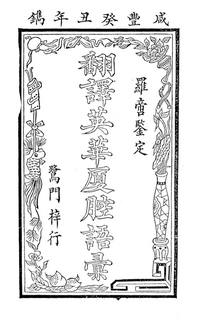

A sample of pe̍h-ōe-jī text | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Southern Min

|

| Creator | Walter Henry Medhurst Elihu Doty John Van Nest Talmage |

Time period | since the 1830s |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | TLPA Taiwanese Romanization System |

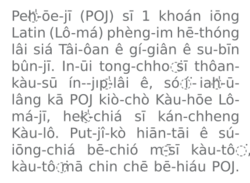

Pe̍h-ōe-jī (nan-TW, English approximation: /ˌpɛɔɪdʒiː/ PEH-oy-JEE; abbr. POJ; lit. vernacular writing), sometimes known as Church Romanization, is an orthography used to write variants of Southern Min Chinese,[1] particularly Taiwanese and Amoy Hokkien, and it is widely employed as one of the writing systems for Southern Min. During its peak, it had hundreds of thousands of readers.[2]

Developed by Western missionaries working among the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia in the 19th century and refined by missionaries working in Xiamen and Tainan, it uses a modified Latin alphabet and some diacritics to represent the spoken language. After initial success in Fujian, POJ became most widespread in Taiwan and, in the mid-20th century, there were over 100,000 people literate in POJ. A large amount of printed material, religious and secular, has been produced in the script, including Taiwan's first newspaper, the Taiwan Church News.

During Japanese rule (1895–1945), the use of pe̍h-ōe-jī was suppressed and Taiwanese kana encouraged; it faced further suppression during the Kuomintang martial law period (1947–1987). In Fujian, use declined after the establishment of the People's Republic of China (1949) and by the early 21st century the system was not in general use there. However, Taiwanese Christians, non-native learners of Southern Min, and native-speaker enthusiasts in Taiwan are among those that continue to use pe̍h-ōe-jī. Full computer support was achieved in 2004 with the release of Unicode 4.1.0, and POJ is now implemented in many fonts, input methods, and is used in extensive online dictionaries.

Versions of pe̍h-ōe-jī have been devised for other Southern Chinese varieties, including Hakka and Teochew Southern Min. Other related scripts include Pha̍k-oa-chhi for Gan, Pha̍k-fa-sṳ for Hakka, Bǽh-oe-tu for Hainanese, Bàng-uâ-cê for Fuzhou, Pe̍h-ūe-jī for Teochew, Gṳ̿ing-nǎing Lô̤-mǎ-cī for Northern Min, and Hing-hua̍ báⁿ-uā-ci̍ for Pu-Xian Min.

In 2006, the Taiwanese Romanization System (Tâi-lô), a government-sponsored successor based on pe̍h-ōe-jī, was released. Despite this, native language education, and writing systems for Taiwanese, have remained a fiercely debated topic in Taiwan.

POJ laid the foundation for the creation of new literature in Taiwan. Before the 1920s, many people had already written literary works in POJ,[3] contributing significantly to the preservation of Southern Min vocabulary since the late 19th century. On October 14, 2006, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan announced the Taiwanese Romanization System or Tâi-lô based on POJ as the standard spelling system for Southern Min.

Name

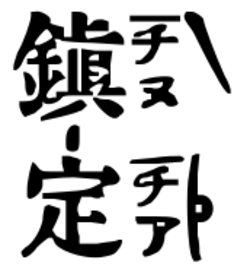

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī |

|---|

The name pe̍h-ōe-jī (Chinese: 白話字; pinyin: Báihuà zì) means "vernacular writing", written characters representing everyday spoken language.[4] The name vernacular writing could be applied to many kinds of writing, romanized and character-based, but the term pe̍h-ōe-jī is commonly restricted to the Southern Min romanization system developed by Presbyterian missionaries in the 19th century.[5]

The missionaries who invented and refined the system used, instead of the name pe̍h-ōe-jī, various other terms, such as "Romanized Amoy Vernacular" and "Romanized Amoy Colloquial."[4] The origins of the system and its extensive use in the Christian community have led to it being known by some modern writers as "Church Romanization" (教會羅馬字; Kàu-hōe Lô-má-jī; Jiàohuì Luōmǎzì) and is often abbreviated in POJ itself to Kàu-lô. (教羅; Jiàoluō)[6] There is some debate on whether "pe̍h-ōe-jī" or "Church Romanization" is the more appropriate name.

Objections to "pe̍h-ōe-jī" are that it can refer to more than one system and that both literary and colloquial register Southern Min appear in the system and so describing it as "vernacular" writing might be inaccurate.[4] Objections to "Church Romanization" are that some non-Christians and some secular writing use it.[7] POJ today is largely disassociated from its former religious purpose.[8] The term "romanization" is also disliked by some, who see it as belittling the status of pe̍h-ōe-jī by identifying it as a supplementary phonetic system instead of a standalone orthography.[7]

History

The history of pe̍h-ōe-jī has been heavily influenced by official attitudes towards the Southern Min vernaculars and the Christian organizations that propagated it. Early documents point to the purpose of the creation of POJ as being pedagogical in nature, closely allied to educating Christian converts.[9]

Early development

The first people to use a romanized script to write Southern Min were Spanish missionaries in Manila in the 16th century.[5] However, it was used mainly as a teaching aid for Spanish learners of Southern Min, and seems not to have had any influence on the development of pe̍h-ōe-jī.[10] In the early 19th century, China was closed to Christian missionaries, who instead proselytized to overseas Chinese communities in South East Asia.[11] The earliest origins of the system are found in a small vocabulary first printed in 1820 by Walter Henry Medhurst,[12][13] who went on to publish the Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms in 1832.[12]

This dictionary represents the first major reference work in POJ, although the romanization within was quite different from the modern system, and has been dubbed Early Church Romanization by one scholar of the subject.[6] Medhurst, who was stationed in Malacca, was influenced by Robert Morrison's romanization of Mandarin Chinese, but had to innovate in several areas to reflect major differences between Mandarin and Southern Min.[14] Several important developments occurred in Medhurst's work, especially the application of consistent tone markings (influenced by contemporary linguistic studies of Sanskrit, which was becoming of more mainstream interest to Western scholars).[15] Medhurst was convinced that accurate representation and reproduction of the tonal structure of Southern Min was vital to comprehension:

Respecting these tones of the Chinese language, some difference of opinion has been obtained, and while some have considered them of first importance, others have paid them little or no intention. The author inclines decidedly to the former opinion; having found, from uniform experience, that without strict attention to tones, it is impossible for a person to make himself understood in Hok-këèn.—W. H. Medhurst[16]

The system expounded by Medhurst influenced later dictionary compilers with regard to tonal notation and initials, but both his complicated vowel system and his emphasis on the literary register of Southern Min were dropped by later writers.[17][18] Following on from Medhurst's work, Samuel Wells Williams became the chief proponent of major changes in the orthography devised by Morrison and adapted by Medhurst. Through personal communication and letters and articles printed in The Chinese Repository a consensus was arrived at for the new version of POJ, although Williams' suggestions were largely not followed.[19]

The first major work to represent this new orthography was Elihu Doty's Anglo-Chinese Manual with Romanized Colloquial in the Amoy Dialect,[19] published in 1853. The manual can therefore be regarded as the first presentation of a pre-modern POJ, a significant step onwards from Medhurst's orthography and different from today's system in only a few details.[20] From this point on various authors adjusted some of the consonants and vowels, but the system of tone marks from Doty's Manual survives intact in modern POJ.[21] John Van Nest Talmage has traditionally been regarded as the founder of POJ among the community which uses the orthography, although it now seems that he was an early promoter of the system, rather than its inventor.[13][19]

In 1842 the Treaty of Nanking was concluded, which included among its provisions the creation of treaty ports in which Christian missionaries would be free to preach.[9] Xiamen (then known as Amoy) was one of these treaty ports, and British, Canadian and American missionaries moved in to start preaching to the local inhabitants. These missionaries, housed in the cantonment of Gulangyu, created reference works and religious tracts, including a bible translation.[9] Naturally, they based the pronunciation of their romanization on the speech of Xiamen, which became the de facto standard when they eventually moved into other areas of the Hokkien Sprachraum, most notably Taiwan.[22] The 1858 Treaty of Tianjin officially opened Taiwan to western missionaries, and missionary societies were quick to send men to work in the field, usually after a sojourn in Xiamen to acquire the rudiments of the language.[22]

Maturity

Because the characters in your country are so difficult only a few people are literate. Therefore, we have striven to print books in pe̍h-ōe-jī to help you to read... don't think that if you know Chinese characters you needn't learn this script, nor should you regard it as a childish thing.

Thomas Barclay, Tâi-oân-hú-siâⁿ Kàu-hōe-pò, Issue 1

Quanzhou and Zhangzhou are two major varieties of Southern Min, and in Xiamen they combined to form something "not Quan, not Zhang" – i.e. not one or the other, but rather a fusion, which became known as Amoy Dialect or Amoy Chinese.[23] In Taiwan, with its mixture of migrants from both Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, the linguistic situation was similar; although the resulting blend in the southern city of Tainan differed from the Xiamen blend, it was close enough that the missionaries could ignore the differences and import their system wholesale.[22]

The fact that religious tracts, dictionaries, and teaching guides already existed in the Xiamen tongue meant that the missionaries in Taiwan could begin proselytizing immediately, without the intervening time needed to write those materials.[24] Missionary opinion was divided on whether POJ was desirable as an end in itself as a full-fledged orthography, or as a means to literacy in Chinese characters. William Campbell described POJ as a step on the road to reading and writing the characters, claiming that to promote it as an independent writing system would inflame nationalist passions in China, where characters were considered a sacred part of Chinese culture.[25] Taking the other side, Thomas Barclay believed that literacy in POJ should be a goal rather than a waypoint:

Soon after my arrival in Formosa I became firmly convinced of three things, and more than fifty years experience has strengthened my conviction. The first was that if you are to have a healthy, living Church it is necessary that all the members, men and women, read the Scriptures for themselves; second, that this end can never be attained by the use of the Chinese character; third, that it can be attained by the use of the alphabetic script, this Romanised Vernacular.—Thomas Barclay[26]

A great boon to the promotion of POJ in Taiwan came in 1880 when James Laidlaw Maxwell, a medical missionary based in Tainan, started promoting POJ for writing the Bible, hymns, newspapers, and magazines. He donated a small printing press to the local church,[27] which Thomas Barclay learned how to operate in 1881 before founding the Presbyterian Church Press in 1884. Subsequently, the Taiwan Prefectural City Church News, which first appeared in 1885 and was produced by Barclay's Presbyterian Church of Taiwan Press,[27] became the first printed newspaper in Taiwan,[28] marking the establishment of POJ in Taiwan, giving rise to numerous literary works written in POJ.[1]

As other authors made their own alterations to the conventions laid down by Medhurst and Doty, pe̍h-ōe-jī evolved and eventually settled into its current form. Ernest Tipson's 1934 pocket dictionary was the first reference work to reflect this modern spelling.[29] Between Medhurst's dictionary of 1832 and the standardization of POJ in Tipson's time, there were a number of works published, which can be used to chart the change over time of pe̍h-ōe-jī:[30]

| Year | Author | Pe̍h-ōe-jī spellings comparison | Source | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [tɕ] | [ts] | [ŋ] [ŋ] | [ɪɛn]/[ɛn] | [iɛt̚] | [ɪk] | [iŋ] | [ɔ] | [◌ʰ] | |||

| 1832 | Medhurst | ch | gn | ëen | ëet | ek | eng | oe | 'h | [31] | |

| 1853 | Doty | ch | ng | ian | iat | iek | ieng | o͘ | ' | [32] | |

| 1869 | MacGowan | ts | ng | ien | iet | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [33] | |

| 1873 | Douglas | ch | ts | ng | ien | iet | ek | eng | ɵ͘ | h | [34] |

| 1894 | Van Nest Talmage | ch | ng | ian | iat | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [35] | |

| 1911 | Warnshuis & de Pree | ch | ng | ian | iat | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [36] | |

| 1913 | Campbell | ch | ts | ng | ian | iat | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [37] |

| 1923 | Barclay | ch | ts | ng | ian | iet | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [38] |

| 1934 | Tipson | ch | ng | ian | iat | ek | eng | o͘ | h | [39] | |

Competition for POJ was introduced during the Japanese era in Taiwan (1895–1945) in the form of Taiwanese kana, a system designed as a teaching aid and pronunciation guide, rather than an independent orthography like POJ.[40]

During the Japanese rule period, the Japanese government began suppressing POJ, banning classes,[2] and forcing the cessation of publications like the Taiwan Church News. From the 1930s onwards, with the increasing militarization of Japan and the Kōminka movement encouraging Taiwanese people to "Japanize", there were a raft of measures taken against native languages, including Taiwanese.[41] While these moves resulted in a suppression of POJ, they were "a logical consequence of increasing the amount of education in Japanese, rather than an explicit attempt to ban a particular Taiwanese orthography in favor of Taiwanese kana".[42]

The Second Sino-Japanese War beginning in 1937 brought stricter measures into force, and along with the outlawing of romanized Taiwanese, various publications were prohibited and Confucian-style shobō (Chinese: 書房; pinyin: shūfáng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: su-pâng) – private schools which taught Classical Chinese with literary Southern Min pronunciation – were closed down in 1939.[43] The Japanese authorities came to perceive POJ as an obstacle to Japanization and also suspected that POJ was being used to hide "concealed codes and secret revolutionary messages".[44] In the climate of the ongoing war the government banned the Taiwan Church News in 1942 as it was written in POJ.[45]

After World War II

Initially the Kuomintang government in Taiwan had a liberal attitude towards "local dialects" (i.e. non-Mandarin varieties of Chinese). The National Languages Committee produced booklets outlining versions of Zhuyin fuhao for writing the Taiwanese tongue, these being intended for newly arrived government officials from outside Taiwan as well as local Taiwanese.[46] The first government action against native languages came in 1953, when the use of Taiwanese or Japanese for instruction was forbidden.[47] The next move to suppress the movement came in 1955, when the use of POJ for proselytizing was outlawed.[45] At that point in time there were 115,000 people literate in POJ in Taiwan, Fujian, and southeast Asia.[48]

Two years later, missionaries were banned from using romanized bibles, and the use of "native languages" (i.e. Taiwanese Hokkien, Hakka, and the non-Sinitic Formosan languages) in church work became illegal.[45] The ban on POJ bibles was overturned in 1959, but churches were "encouraged" to use character bibles instead.[45] Government activities against POJ intensified in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when several publications were banned or seized in an effort to prevent the spread of the romanization. In 1964, use of Taiwanese in schools or official settings was forbidden,[47] and transgression in schools was punished with beatings, fines and humiliation.[49] The Taiwan Church News (printed in POJ) was banned in 1969, and only allowed to return a year later when the publishers agreed to print it in Chinese characters.[45][50] In the 1970s, the Nationalist government in Taiwan completely prohibited the use of POJ, causing it to decline.[51]

In 1974, the Government Information Office banned A Dictionary of Southern Min, with a government official saying: "We have no objection to the dictionary being used by foreigners. They could use it in mimeographed form. But we don't want it published as a book and sold publicly because of the Romanization it contains. Chinese should not be learning Chinese through Romanization."[52] Also in the 1970s, a POJ New Testament translation known as the "Red Cover Bible" (Âng-phoê Sèng-keng) was confiscated and banned by the Nationalist regime.[53] Official moves against native languages continued into the 1980s, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of the Interior decided in 1984 to forbid missionaries to use "local dialects" and romanizations in their work.[45]

It wasn't until the late 1980s, with the lifting of martial law, that POJ slowly regained momentum under the influence of the native language movement. With the ending of martial law in 1987, the restrictions on "local languages" were quietly lifted,[54] resulting in growing interest in Taiwanese writing during the 1990s.[55] For the first time since the 1950s, Taiwanese language and literature was discussed and debated openly in newspapers and journals.[56] There was also support from the then opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party, for writing in the language.[47] From a total of 26 documented orthographies for Taiwanese in 1987 (including defunct systems), there were a further 38 invented from 1987 to 1999, including 30 different romanizations, six adaptations of bopomofo and two hangul-like systems.[57] Some commentators believe that the Kuomintang, while steering clear of outright banning of the native language movements after the end of martial law, took a "divide and conquer" approach by promoting Taiwanese Language Phonetic Alphabet (TLPA), an alternative to POJ,[58] which was at the time the choice of the majority within the nativization movement.[59]

Native language education has remained a fiercely debated topic in Taiwan into the 21st century and is the subject of much political wrangling.[60][61]

Current system

The current system of pe̍h-ōe-jī has been stable since the 1930s, with a few minor exceptions (detailed below).[62] There is a fair degree of similarity with the Vietnamese alphabet, including the ⟨b/p/ph⟩ distinction and the use of ⟨ơ⟩ in Vietnamese compared with ⟨o͘⟩ in POJ.[63] POJ uses the following letters and combinations:[64]

| Capital letters | A | B | CH | CHH | E | G | H | I | J | K | KH | L | M | N | ᴺ | NG | O | O͘ | P | PH | S | T | TH | U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase letters | a | b | ch | chh | e | g | h | i | j | k | kh | l | m | n | ⁿ | ng | o | o͘ | p | ph | s | t | th | u |

| Letter names | a | be | che | chhe | e | ge | ha | i | ji̍t | ka | kha | é-luh | é-muh | é-nuh | iⁿ | ng | o | o͘ | pe | phe | e-suh | te | the | u |

Chinese phonology traditionally divides syllables in Chinese into three parts; firstly the initial, a consonant or consonant blend which appears at the beginning of the syllable, secondly the final, consisting of a medial vowel (optional), a nucleus vowel, and an optional ending; and finally the tone, which is applied to the whole syllable.[65] In terms of the non-tonal (i.e. phonemic) features, the nucleus vowel is the only required part of a licit syllable in Chinese varieties.[65] Unlike Mandarin but like other southern varieties of Chinese, Taiwanese has final stop consonants with no audible release, a feature that has been preserved from Middle Chinese.[66] There is some debate as to whether these stops are a tonal feature or a phonemic one, with some authorities distinguishing between ⟨-h⟩ as a tonal feature, and ⟨-p⟩, ⟨-t⟩, and ⟨-k⟩ as phonemic features.[67] Southern Min dialects also have an optional nasal property, which is written with a superscript ⟨ⁿ⟩ and usually identified as being part of the vowel.[68] Vowel nasalisation also occurs in words that have nasal initials (⟨m-⟩, ⟨n-⟩, ⟨ng-⟩),[69] however in this case superscript ⟨ⁿ⟩ is not written, e.g. Template:Zhi nūi (nan).[64] The letter ⁿ appears at the end of a word except in some interjections, such as haⁿh (nan), however more conservative users of Pe̍h-ōe-jī write such words as hahⁿ.

A valid syllable in Hokkien takes the form (initial) + (medial vowel) + nucleus + (stop) + tone, where items in parentheses indicate optional components.[70]

The initials are:[71]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m [m] ㄇ 毛 (mo͘) |

n [n] ㄋ 耐 (nāi) |

ng [ŋ] ㄫ 雅 (ngá) |

|||

| Stop | Unaspirated | p [p] ㄅ 邊 (pian) |

t [t] ㄉ 地 (tē) |

k [k] ㄍ 求 (kiû) |

||

| Aspirated | ph [pʰ] ㄆ 波 (pho) |

th [tʰ] ㄊ 他 (thaⁿ) |

kh [kʰ] ㄎ 去 (khì) |

|||

| Voiced | b [b] ㆠ 文 (bûn) |

g [ɡ] ㆣ 語 (gí) |

||||

| Affricate | Unaspirated | ch [ts] ㄗ 曾 (chan) |

chi [tɕ] ㄐ 尖 (chiam) |

|||

| Aspirated | chh [tsʰ] ㄘ 出 (chhut) |

chhi [tɕʰ] ㄑ 手 (chhiú) |

||||

| Voiced | j [dz] ㆡ 熱 (joa̍h) |

ji [dʑ] ㆢ 入 (ji̍p) |

||||

| Fricative | s [s] ㄙ 衫 (saⁿ) |

si [ɕ] ㄒ 寫 (siá) |

h [h] ㄏ 喜 (hí) | |||

| Lateral | l [ɭ/ɾ] ㄌ 柳 (liú) |

|||||

Vowels:[72]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coda endings:

|

|

POJ has a limited amount of legitimate syllables, although sources disagree on some particular instances of these syllables. The following table contains all the licit spellings of POJ syllables, based on a number of sources:

| Licit POJ syllables | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Campbell,[73] Embree,[74] Kì.[75] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tone markings

| No. | Diacritic | Chinese tone name | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | 陰平 (yīnpíng) dark level |

kha 跤 foot; leg |

| 2 | acute | 上聲 (shǎngshēng) rising |

chúi 水 water |

| 3 | grave | 陰去 (yīnqù) dark departing |

kàu 到 arrive |

| 4 | N/A | 陰入 (yīnrù) dark entering |

bah 肉 meat |

| 5 | circumflex | 陽平 (yángpíng) light level |

ông 王 king |

| 7 | macron | 陽去 (yángqù) light departing |

tiōng 重 heavy |

| 8 | vertical line above | 陽入 (yángrù) light entering |

joa̍h 熱 hot |

In standard Amoy or Taiwanese Hokkien there are seven distinct tones, which by convention are numbered 1–8, with number 6 omitted (tone 6 used to be a distinct tone, but has long since merged with tone 7 or 2 depending on lexical register). Tones 1 and 4 are both represented without a diacritic, and can be distinguished from each other by the syllable ending, which is a vowel, ⟨-n⟩, ⟨-m⟩, or ⟨-ng⟩ for tone 1, and ⟨-h⟩, ⟨-k⟩, ⟨-p⟩, and ⟨-t⟩ for tone 4.

Southern Min dialects undergo considerable tone sandhi, i.e. changes to the tone depending on the position of the syllable in any given sentence or utterance.[70] However, like pinyin for Mandarin Chinese, POJ always marks the citation tone (i.e. the original, pre-sandhi tone) rather than the tone which is actually spoken.[76] This means that when reading aloud the reader must adjust the tone markings on the page to account for sandhi. Some textbooks for learners of Southern Min mark both the citation tone and the sandhi tone to assist the learner.[77]

There is some debate as to the correct placement of tone marks in the case of diphthongs and triphthongs, particularly those which include ⟨oa⟩ and ⟨oe⟩.[78] Most modern writers follow six rules:[79]

- If the syllable has one vowel, that vowel should be tone-marked; viz. ⟨tī⟩, ⟨láng⟩, ⟨chhu̍t⟩

- If a diphthong contains ⟨i⟩ or ⟨u⟩, the tone mark goes above the other vowel; viz. ⟨ia̍h⟩, ⟨kiò⟩, ⟨táu⟩

- If a diphthong includes both ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩, mark the ⟨u⟩; viz. ⟨iû⟩, ⟨ùi⟩

- If the final is made up of three or more letters, mark the second vowel (except when rules 2 and 3 apply); viz. ⟨goán⟩, ⟨oāi⟩, ⟨khiáu⟩

- If ⟨o⟩ occurs with ⟨a⟩ or ⟨e⟩, mark the ⟨o⟩ (except when rule 4 applies); viz. ⟨òa⟩, ⟨thóe⟩

- If the syllable has no vowel, mark the nasal consonant; viz. ⟨m̄⟩, ⟨ǹg⟩, ⟨mn̂g⟩

Hyphens

A single hyphen is used to indicate a compound. What constitutes a compound is controversial, with some authors equating it to a "word" in English, and others not willing to limit it to the English concept of a word.[78] Examples from POJ include ⟨sì-cha̍p⟩ "forty", ⟨bé-hì-thôan⟩ "circus", and ⟨hôe-ho̍k⟩ "recover (from illness)". The non-final syllables of a compound typically undergo tone sandhi, but exact rules have not been clearly identified by linguists.[80]

A double hyphen ⟨--⟩ is used when POJ is deployed as an orthography (rather than as a transcription system) to indicate that the following syllable should be pronounced in the neutral tone.[81] It also marks to the reader that the preceding syllable does not undergo tone sandhi, as it would were the following syllable non-neutral. Morphemes following a double hyphen are often (but not always) grammatical function words.[82] Some authors use an interpunct ⟨·⟩ in place of the second hyphen.

Audio examples

| POJ | Translation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Sian-siⁿ kóng, ha̍k-seng tiām-tiām thiaⁿ. | A teacher/master speaks, students quietly listen. | |

| Kin-á-jit hit-ê cha-bó͘ gín-á lâi góan tau khòaⁿ góa. | Today that girl came to my house to see me. | |

| Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá--bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē--ô͘! | Space friends, how are you? Have you eaten yet? When you have the time, come on over to eat. | Listen (from NASA Voyager Golden Record) |

Regional differences

In addition to the standard syllables detailed above, there are several regional variations of Hokkien which can be represented with non-standard or semi-standard spellings. In the Zhangzhou-type varieties, spoken in Zhangzhou, parts of Taiwan (particularly the northeastern coast around Yilan City), and parts of Malaysia (particularly in Penang), there is a final ⟨-uiⁿ⟩, for example in "egg" ⟨nūi⟩ and "cooked rice" ⟨pūiⁿ⟩, which has merged with ⟨-ng⟩ in mainstream Taiwanese.[83] Zhangzhou-type varieties may also have the vowel /ɛ/, written as ⟨ɛ⟩[84][85][86] or ⟨e͘ ⟩ (with a dot above right, by analogy with ⟨o͘ ⟩),[86] which has merged with ⟨e⟩ in Taiwanese.

Texts

Genesis 1:1–5[87]

Due to POJ's origins in the Christian church, much of the material in the script is religious in nature, including several Bible translations, books of hymns, and guides to morality. The Tainan Church Press, established in 1884, has been printing POJ materials ever since, with periods of quiet when POJ was suppressed in the early 1940s and from around 1955 to 1987. In the period to 1955, over 2.3 million volumes of POJ books were printed,[88] and one study in 2002 catalogued 840 different POJ texts in existence.[89] Besides a Southern Min version of Wikipedia in the orthography,[90] there are teaching materials, religious texts, and books about linguistics, medicine and geography.

- Lán ê Kiù-chú Iâ-so͘ Ki-tok ê Sin-iok (1873 translation of the New Testament)

- Lāi-goā-kho Khàn-hō͘-ha̍k, by George Gushue-Taylor, 1917

- Chinese–English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy, by Carstairs Douglas, 1873

- Lear Ông, translation of King Lear by Tē Hūi-hun

Computing

POJ was initially not well supported by word-processing applications due to the special diacritics needed to write it. Support has now improved and there are now sufficient resources to both enter and display POJ correctly. Several input methods exist to enter Unicode-compliant POJ, including OpenVanilla (macOS and Microsoft Windows), the cross-platform Tai-lo Input Method released by the Taiwanese Ministry of Education, and the Firefox add-on Transliterator, which allows in-browser POJ input.[91] When POJ was first used in word-processing applications it was not fully supported by the Unicode standard, thus necessitating work-arounds. One employed was encoding the necessary characters in the "Private Use" section of Unicode, but this required both the writer and the reader to have the correct custom font installed.[92] Another solution was to replace troublesome characters with near equivalents, for example substituting ⟨ä⟩ for ⟨ā⟩ or using a standard ⟨o⟩ followed by an interpunct to represent ⟨o͘⟩.[92] With the introduction into Unicode 4.1.0 of the combining character U+0358 ◌͘ COMBINING DOT ABOVE RIGHT in 2004, all the necessary characters were present to write regular POJ without the need for workarounds.[93][94] However, even after the addition of these characters, there are still relatively few fonts which are able to properly render the script, including the combining characters.

Unicode codepoints

The following are tone characters and their respective Unicode codepoints used in POJ. The tones used by POJ should use Combining Diacritical Marks instead of Spacing Modifier Letters used by bopomofo.[95][96] As POJ is not encoded in Big5, the prevalent encoding used in Traditional Chinese, some POJ letters are not directly encoded in Unicode, instead should be typed using combining diacritical marks officially.[97]

| Base letter/Tone 1 | Tone 2 | Tone 3 | Tone 4 | Tone 5 | Tone 7 | Tone 8 | Variant | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combining mark | ́ (U+0301) | ̀ (U+0300) | h | ̂ (U+0302) | ̄ (U+0304) | ̍h (U+030D) | ˘ (U+0306) | |||||||||

| One mark | ||||||||||||||||

| Uppercase | A | Á (U+00C1) | À (U+00C0) | AH | Â (U+00C2) | Ā (U+0100) | A̍H (U+0041 U+030D) | Ă (U+0102) | ||||||||

| E | É (U+00C9) | È (U+00C8) | EH | Ê (U+00CA) | Ē (U+0112) | E̍H (U+0045 U+030D) | Ĕ (U+0114) | |||||||||

| I | Í (U+00CD) | Ì (U+00CC) | IH | Î (U+00CE) | Ī (U+012A) | I̍H (U+0049 U+030D) | Ĭ (U+012C) | |||||||||

| O | Ó (U+00D3) | Ò (U+00D2) | OH | Ô (U+00D4) | Ō (U+014C) | O̍H (U+004F U+030D) | Ŏ (U+014E) | |||||||||

| U | Ú (U+00DA) | Ù (U+00D9) | UH | Û (U+00DB) | Ū (U+016A) | U̍H (U+0055 U+030D) | Ŭ (U+016C) | |||||||||

| M | Ḿ (U+1E3E) | M̀ (U+004D U+0300) | MH | M̂ (U+004D U+0302) | M̄ (U+004D U+0304) | M̍H (U+004D U+030D) | M̆ (U+004D U+0306) | |||||||||

| N | Ń (U+0143) | Ǹ (U+01F8) | NH | N̂ (U+004E U+0302) | N̄ (U+004E U+0304) | N̍H (U+004E U+030D) | N̆ (U+004E U+0306) | |||||||||

| Lowercase | a | á (U+00E1) | à (U+00E0) | ah | â (U+00E2) | ā (U+0101) | a̍h (U+0061 U+030D) | ă (U+0103) | ||||||||

| e | é (U+00E9) | è (U+00E8) | eh | ê (U+00EA) | ē (U+0113) | e̍h (U+0065 U+030D) | ĕ (U+0115) | |||||||||

| i | í (U+00ED) | ì (U+00EC) | ih | î (U+00EE) | ī (U+012B) | i̍h (U+0069 U+030D) | ĭ (U+012D) | |||||||||

| o | ó (U+00F3) | ò (U+00F2) | oh | ô (U+00F4) | ō (U+014D) | o̍h (U+006F U+030D) | ŏ (U+014F) | |||||||||

| u | ú (U+00FA) | ù (U+00F9) | uh | û (U+00FB) | ū (U+016B) | u̍h (U+0075 U+030D) | ŭ (U+016D) | |||||||||

| m | ḿ (U+1E3F) | m̀ (U+006D U+0300) | mh | m̂ (U+006D U+0302) | m̄ (U+006D U+0304) | m̍h (U+006D U+030D) | m̆ (U+006D U+0306) | |||||||||

| n | ń (U+0144) | ǹ (U+01F9) | nh | n̂ (U+006E U+0302) | n̄ (U+006E U+0304) | n̍h (U+006E U+030D) | n̆ (U+006E U+0306) | |||||||||

| Two tones [2] | ||||||||||||||||

| Uppercase | O͘ (U+004F U+0358) | Ó͘ | Ò͘ | O͘H | Ô͘ | Ō͘ | O̍͘H | Ŏ͘ | ||||||||

| Lowercase | o͘ (U+006F U+0358) | ó͘ | ò͘ | o͘h | ô͘ | ō͘ | o̍͘h | ŏ͘ | ||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Superscript n is also required for POJ to indicate nasalisation:

| Character | Unicode codepoint |

|---|---|

| U+207F | |

| U+1D3A |

Characters not directly encoded in Unicode (especially O͘ series which has 3 different permutations) requires premade glyphs in fonts in order for applications to correctly display the characters.[96]

Font support

Fonts that currently support POJ includes:

- Charis SIL

- DejaVu

- Doulos SIL

- Linux Libertine

- Taigi Unicode

- Source Sans Pro[98][99][92]

- I.Ming (8.00 onwards) from Ichiten Font Project

- Fonts made by justfont foundry[96]

- Fonts modified and release in GitHub repository POJFonts : POJ Phiaute, Gochi Hand POJ, Nunito POJ, POJ Vibes, and POJ Garamond.

- Fonts modified and released by But Ko based on Source Han Sans: Genyog, Genseki, Gensen ; based on Source Han Serif: Genyo, Genwan, Genryu.

Han-Romanization mixed script

Sample mixed orthography text[100]

One of the most popular modern ways of writing Taiwanese is by using a mixed orthography[101] called Hàn-lô[102] (simplified Chinese: 汉罗; traditional Chinese: 漢羅; pinyin: Hàn-Luó; literally Chinese-Roman), and sometimes Han-Romanization mixed script, a style not unlike written Japanese or (historically) Korean.[103] In fact, the term Hàn-lô does not describe one specific system, but covers any kind of writing in Southern Min which features both Chinese characters and romanization.[101] That romanization is usually POJ, although recently some texts have begun appearing with Taiwanese Romanization System (Tâi-lô) spellings too. The problem with using only Chinese characters to write Southern Min is that there are many morphemes (estimated to be around 15 percent of running text)[104] which are not definitively associated with a particular character. Various strategies have been developed to deal with the issue, including creating new characters, allocating Chinese characters used in written Mandarin with similar meanings (but dissimilar etymology) to represent the missing characters, or using romanization for the "missing 15%".[105] There are two rationales for using mixed orthography writing, with two different aims. The first is to allow native speakers (almost all of whom can already write Chinese characters) to make use of their knowledge of characters, while replacing the missing 15% with romanization.[101] The second is to wean character literates off using them gradually, to be replaced eventually by fully romanized text.[106] Examples of modern texts in Hàn-lô include religious, pedagogical, scholarly, and literary works, such as:

Adaptations for other Chinese varieties

POJ has been adapted for several other varieties of Chinese, with varying degrees of success. For Hakka, missionaries and others have produced a Bible translation, hymn book, textbooks, and dictionaries.[109] Materials produced in the orthography, called Pha̍k-fa-sṳ, include:

- Hak-ngi Sṳn-kin, Sin-yuk lau Sṳ-phien: Hien-thoi Thoi-van Hak-ngi Yit-pun (Hakka Bible, New Testament and Psalms: Today's Taiwan Hakka Version). Bible Society. 1993.

- Phang Tet-siu (1994). Thai-ka Loi Hok Hak-fa (Everybody Learn Hakka). Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 957-638-017-0.

- Phang Tet-siu (1996). Hak-ka-fa Fat-yim Sṳ-tien (Hakka Pronunciation Dictionary). Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 957-638-359-5.

- Hak-ka Sṳn-sṳ (Hakka Hymns). Tainan: PCT Press. 1999. ISBN 957-8349-75-0.

A modified version of POJ has also been created for Teochew.[110]

Current status

Most native Southern Min speakers in Taiwan are unfamiliar with POJ or any other writing system,[111] commonly asserting that "Taiwanese has no writing",[112] or, if they are made aware of POJ, considering romanization as the "low" form of writing, in contrast with the "high" form (Chinese characters).[113] For those who are introduced to POJ alongside Hàn-lô and completely Chinese character-based systems, a clear preference has been shown for all-character systems, with all-romanization systems at the bottom of the preference list, likely because of the preexisting familiarity of readers with Chinese characters.[114]

POJ remains the Taiwanese orthography "with the richest inventory of written work, including dictionaries, textbooks, literature [...] and other publications in many areas".[115] A 1999 estimate put the number of literate POJ users at around 100,000,[116] and secular organizations have been formed to promote the use of romanization among Taiwanese speakers.[117]

Outside Taiwan, POJ is rarely used. For example, in Fujian, Xiamen University uses a romanization known as Bbánlám pìngyīm, based on Pinyin. In other areas where Hokkien is spoken, such as Singapore, the Speak Mandarin Campaign is underway to actively discourage people from speaking Hokkien or other non-Mandarin varieties in favour of switching to Mandarin instead.[118]

In 2006, Taiwan's Ministry of Education chose an official romanization for use in teaching Southern Min in the state school system.[119] POJ was one of the candidate systems, along with Daī-ghî tōng-iōng pīng-im, but a compromise system, the Taiwanese Romanization System or Tâi-lô, was chosen in the end.[120] Tâi-Lô retains most of the orthographic standards of POJ, including the tone marks, while changing the troublesome ⟨o͘⟩ character for ⟨oo⟩, swapping ⟨ts⟩ for ⟨ch⟩, and replacing ⟨o⟩ in diphthongs with ⟨u⟩.[121] Supporters of Taiwanese writing are in general deeply suspicious of government involvement, given the history of official suppression of native languages,[8] making it unclear whether Tâi-lô or POJ will become the dominant system in the future.

Notes

References

| Chinese romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Min |

| Gan |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

| See also |

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tân, Bō͘-Chin (2015) (in zh). National Taiwan Normal University. pp. 1, 5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sakai, Tōru (2003-06-11) (in zh).

- ↑ Chiúⁿ, Ûi-bûn (2005) (in zh). National Cheng Kung University.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Klöter (2005), p. 90.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Klöter (2002), p. 1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Klöter (2005), p. 89.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chang (2001), p. 13.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Klöter (2005), p. 248.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Klöter (2005), p. 92.

- ↑ Klöter (2002), p. 2.

- ↑ Heylen (2001), p. 139.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Heylen (2001), p. 142.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chang (2001), p. 14.

- ↑ Heylen (2001), p. 144.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 109.

- ↑ Medhurst (1832), p. viii.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 110.

- ↑ Heylen (2001), p. 145.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Heylen (2001), p. 149.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 111.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), pp. 111, 116.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Klöter (2005), p. 93.

- ↑ Ang (1992), p. 2.

- ↑ Heylen (2001), p. 160.

- ↑ Klöter (2002), p. 13.

- ↑ Quoted in Band (1936), p. 67

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Our Story". Taiwan Church News. http://enews.pctpress.org/about_us.htm.

- ↑ Copper (2007), p. 240.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 114.

- ↑ Adapted from Klöter (2005), pp. 113–6

- ↑ Medhurst (1832).

- ↑ Doty (1853).

- ↑ MacGowan (1869).

- ↑ Douglas (1873).

- ↑ Van Nest Talmage (1894).

- ↑ Warnshuis & de Pree (1911).

- ↑ Campbell (1913).

- ↑ Barclay (1923).

- ↑ Tipson (1934).

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 136.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 153.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 154.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 135.

- ↑ Lin (1999), p. 21.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Chang (2001), p. 18.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 231.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Lin (1999), p. 1.

- ↑ Tiuⁿ (2004), p. 7.

- ↑ Sandel (2003), p. 533.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 217.

- ↑ Chiúⁿ, Ûi-bûn (2013). "教會內台語白話字使用人口kap現況調查". The Journal of Taiwanese Vernacular 5 (1): 74–97.

- ↑ "Guide to Dialect Barred in Taiwan: Dictionary Tried to Render Local Chinese Sounds". New York Times: sec. GN, p. 15. September 15, 1974. https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E02E0DD1E30E234A75756C1A96F9C946590D6CF.; quoted in Lin (1999), p. 22

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 24.

- ↑ Sandel (2003), p. 530.

- ↑ Wu (2007), p. 1.

- ↑ Wu (2007), p. 9.

- ↑ Chiung (2005), p. 275.

- ↑ Chang (2001), p. 19.

- ↑ Chiung (2005), p. 273.

- ↑ Loa Iok-sin (2009-02-28). "Activists demand Hoklo exams". Taipei Times. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2009/02/28/2003437216.

- ↑ "Premier's comments over language status draws anger". China Post. 2003-09-25. http://www.chinapost.com.tw/news/2003/09/25/41604/Premiers-comments.htm.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 98.

- ↑ Chang (2001), p. 15.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Klöter (2005), p. 99.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Chung (1996), p. 78.

- ↑ Norman (1998), p. 237.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 14.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 15.

- ↑ Pan, Ho-hsien (September 2004). "Nasality in Taiwanese". Language and Speech 47 (3): 267–296. doi:10.1177/00238309040470030301. PMID 15697153.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Ramsey (1987), p. 109.

- ↑ Chang (2001), p. 30.

- ↑ Chang (2001), p. 33.

- ↑ Campbell (1913), pp. 1–4: Entries under the initial ts have been tallied under the modern spelling of ch.

- ↑ Embree (1973).

- ↑ Kì (2008), pp. 4–25.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 100.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 101.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Klöter (2005), p. 102.

- ↑ Chang (2001), pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 103.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 103–104.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 104.

- ↑ Chang (2001), p. 134.

- ↑ Douglas Carstairs. "Introduction with Remarks on Pronunciation and Instructions for Use." Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy, etc. New Edition. Presbyterian Church of England, 1899. p. xi.

- ↑ Douglas Carstairs. "Appendix I: Variations of Spelling in Other Books on the Language of Amoy." Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy, etc. New Edition. Presbyterian Church of England, 1899. p. 607.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Tan Siew Imm. Penang Hokkien-English Dictionary, With an English-Penang Hokkien Glossary. Sunway University Press, 2016. pp. iv–v. ISBN:9789671369715

- ↑ Barclay et al. (1933), p. 1.

- ↑ Tiuⁿ (2004), p. 6.

- ↑ Tiuⁿ (2004), p. 8.

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 23.

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 29.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 Iûⁿ (2009), p. 20.

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 11.

- ↑ "Combining Diacritical Marks". unicode.org. p. 34. http://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0300.pdf.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 "aiongg/POJFonts". 2020-11-22. https://github.com/aiongg/POJFonts. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 "談金萱的台羅變音符號設計" (in zh-TW). 2019-01-11. https://blog.justfont.com/2019/01/jinxuan-taiwan-letters/. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ↑ "FAQ – Characters and Combining Marks". http://unicode.org/faq/char_combmark.html#9. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 24

- ↑ "Fonts version 3.006 (OTF, TTF, WOFF, WOFF2, Variable)". Adobe Systems Incorporated. 2010-09-06. https://github.com/adobe-fonts/source-sans-pro/releases/tag/3.006R. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- ↑ Sidaia (1998), p. 264.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 Klöter (2005), p. 225.

- ↑ Ota (2005), p. 21.

- ↑ Iûⁿ (2009), p. 10.

- ↑ Lin (1999), p. 7.

- ↑ Lin (1999), pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Klöter (2005), p. 230.

- ↑ Chang (2001).

- ↑ Sidaia (1998).

- ↑ Wu & Chen (2004).

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in zh). Hailufeng. http://hailufeng.com/detail/?newsid=23156. - ↑ Ota (2005), p. 20.

- ↑ Baran (2004), p. 35–5.

- ↑ Chiung (2005), p. 300.

- ↑ Chiung (2005), p. 301.

- ↑ Chiung (2005), p. 272.

- ↑ Lin (1999), p. 17.

- ↑ Chiung (2007), p. 474.

- ↑ Wong-Anan, Nopporn (2009-09-16). "Eyeing China, Singapore sees Mandarin as its future". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSSIN366189.

- ↑ Tseng (2009), p. 2.

- ↑ (in zh), Central News Agency, http://blog.udn.com/alexandroslee/471006

- ↑ Tseng (2009), pp. 2–5.

Works cited

- Ang, Ui-jin (1992) (in zh). Taiwan Fangyan zhi Lü. Taipei: Avanguard Publishing. ISBN 957-9512-31-0.

- Band, Edward (1936). Barclay of Formosa. Ginza, Tokyo: Christian Literature Society. OCLC 4386066.

- Baran, Dominika (2004). ""Taiwanese don't have written words": Language ideologies and language practice in a Taipei County high school". 2004 International Conference on Taiwanese Romanization. 2. OCLC 77082548.

- Barclay, Thomas; Lun, Un-jîn; Nĝ, Má-hūi; Lu, Iok-tia (1933). Sin-kū-iok ê Sèng-keng. OCLC 48696650.

- Campbell, William (1913). A Dictionary of the Amoy Vernacular spoken throughout the prefectures of Chin-chiu, Chiang-chiu and Formosa. Tainan: Taiwan Church Press. OCLC 867068660. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000072254844.

- Campbell, William (2006). A Dictionary of the Amoy Vernacular. Tainan: PCT Press. ISBN 957-8959-92-3.

- Chang, Yu-hong (2001). Principles of POJ or the Taiwanese Orthography: An Introduction to Its Sound-Symbol Correspondences and Related Issues. Taipei: Crane. ISBN 9789572053072.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo (2003). Learning Efficiencies for Different Orthographies: A Comparative Study of Han Characters and Vietnamese Romanization.' (PhD dissertation). University of Texas at Arlington. http://uibun.twl.ncku.edu.tw/chuliau/lunsoat/english/phd/index.htm.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo (2005). Language, Identity and Decolonization. Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. ISBN 9789578845855.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo (2007). Language, Literature and Reimagined Taiwanese Nation. Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. ISBN 9789860097467.

- Chiung, Wi-vun Taiffalo (2011). Nations, Mother Tongues and Phonemic Writing. Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. ISBN 978-986-02-7359-5.

- Chung, Raung-fu (1996). The Segmental Phonology of Southern Min in Taiwan. Taipei: Spoken Language Services. ISBN 9789579463461. OCLC 36091818.

- Copper, John F. (2007). A Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China) (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810856004.

- Doty, Elihu (1853). Anglo Chinese Manual of the Amoy Dialect. Guangzhou: Samuel Wells Williams. OCLC 20605114.

- Douglas, Carstairs (1873). Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy (1st ed.). London: Trübner. OCLC 4820970. https://archive.org/details/chineseenglish00doug.

- Barclay, Thomas (1923). Supplement to Dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy. Shanghai: The Commercial press, limited.

- Embree, Bernard L. M. (1973). A Dictionary of Southern Min: based on current usage in Taiwan and checked against the earlier works of Carstairs Douglas, Thomas Barclay, and Ernest Tipson. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Language Institute. OCLC 2491446.

- Heylen, Ann (2001). "Romanizing Taiwanese: Codification and Standardization of Dictionaries in Southern Min (1837–1923)". in Ku, Wei-ying; De Ridder, Koen. Authentic Chinese Christianity, Preludes to Its Development: Nineteenth & Twentieth Centuries. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 9789058671028.

- Iûⁿ Ún-giân; Tiuⁿ Ha̍k-khiam (1999). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in zh). Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. http://ws.twl.ncku.edu.tw/hak-chia/i/iunn-ungian/hui-hanji-phengim.htm. - Iûⁿ, Ún-giân (2009). Processing Techniques for Written Taiwanese – Tone Sandhi and POS Tagging (Doctoral dissertation). National Taiwan University. OCLC 367595113.

- Kì, Bō͘-hô (2008). Tainan: PCT Press. ISBN 9789866947346.

- Klöter, Henning (2002). "The History of Peh-oe-ji". Taipei: Taiwanese Romanization Association.

- Klöter, Henning (2005). Written Taiwanese. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 9783447050937.

- Lin, Alvin (1999). "Writing Taiwanese: The Development of Modern Written Taiwanese". Sino-Platonic Papers (89). OCLC 41879041. http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp089_taiwanese.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- MacGowan, John (1869). A Manual of the Amoy Colloquial. Hong Kong: de Souza & Co.. OCLC 23927767.

- Maryknoll Fathers (1984). Taiwanese: Book 1. Taichung: Maryknoll. OCLC 44137703.}

- Medhurst, Walter Henry (1832). Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms. Macau: East India Press. OCLC 5314739.

- Norman, Jerry (1998). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521296536.

- Ong Iok-tek (2002) (in zh). Taiwanyu Yanjiu Juan. Taipei: Avanguard Publishing. ISBN 957-801-354-X.

- Ota, Katsuhiro J. (2005). An investigation of written Taiwanese (PDF) (Master's). University of Hawai'i at Manoa. OCLC 435500061. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691014685.

- Sandel, Todd L. (2003). "Linguistic capital in Taiwan: The KMT's Mandarin language policy and its perceived impact on language practices of bilingual Mandarin and Tai-gi speakers". Language in Society (Cambridge University Press) 32 (4): 523–551. doi:10.1017/S0047404503324030.

- Sidaia, Babuja A. (1998) (in zh-hant). Taipei: Taili. ISBN 9789579886161. OCLC 815099022.

- Tipson, Ernest (1934). A Pocket Dictionary of the Amoy Vernacular: English-Chinese. Singapore: Lithographers. OCLC 504142973.

- Tiuⁿ, Ha̍k-khiam (2004) (in zh). 2004 International Conference on Taiwanese Romanization. 1. OCLC 77082548.

- Tseng, Rui-cheng (2009) (in zh). Taiwan Minnanyu Luomazi Pinyin Fang'an Shiyong Shouce. ROC Ministry of Education. ISBN 9789860166378. http://english.moe.gov.tw/public/Attachment/9851214271.pdf.

- Van Nest Talmage, John (1894). New Dictionary in the Amoy Dialect. OCLC 41548900.

- Warnshuis, A. Livingston; de Pree, H.P. (1911). Lessons in the Amoy Vernacular. Xiamen: Chui-keng-tông Press. OCLC 29903392.

- Wu, Chang-neng (2007). The Taigi Literature Debates and Related Developments (1987–1996) (Master's). Taipei: National Chengchi University. OCLC 642745725. Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2014-12-18.

- Wu, Guo-sheng; Chen, Yi-hsin (2004) (in zh). 2004 International Conference on Taiwanese Romanization. 2. OCLC 77082548.

External links

General

- "Tai-gu Bang". http://groups.google.com.tw/group/taigu/browse_thread/thread/307245daaa08a82a?pli=1. – Google group for Taiwanese language enthusiasts – uses POJ and Chinese characters.

- "Pe̍h-ōe-jī Unicode Correspondence Table". Tailingua. 2009. http://tailingua.com/resources/downloads/pojunicode.pdf. – information on Unicode encodings for POJ text

- "Taiwanese Romanization Association". http://www.tlh.org.tw/. – group dedicated to the promotion of Taiwanese and Hakka romanization

Input methods

- "Open Vanilla". http://openvanilla.org/. – open source input method for both Windows and macOS.

- "Taigi-Hakka IME". http://taigi.fhl.net/TaigiIME/. – Windows-based input method for both Hokkien (with both Pe̍h-ōe-jī and Taiwanese Romanization System input) and Hakka variants.

- "Tai-lo Input Method" (in zh). http://www.edu.tw/pages/detail.aspx?Node=3683&Page=15638&Index=6&WID=c5ad5187-55ef-4811-8219-e946fe04f725. – cross-platform input method released by Taiwan's Ministry of Education.

- "Transliterator". http://www.benya.com/transliterator/. – extension for the Firefox browser which allows POJ input in-browser.

POJ-compliant fonts

- "Charis SIL". SIL International. 2 October 2014. http://scripts.sil.org/cms/scripts/page.php?site_id=nrsi&id=CharisSILFont. – serif font in regular, bold, italic, and bold italic.

- "DejaVu". http://dejavu-fonts.org/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page. – available in serif, sans-serif, and monospace.

- "Doulos SIL". SIL International. 2 October 2014. http://scripts.sil.org/cms/scripts/page.php?site_id=nrsi&id=DoulosSILfont. – Times New Roman-style serif.

- "Gentium". SIL International. 2 October 2014. http://scripts.sil.org/cms/scripts/page.php?site_id=nrsi&id=gentium. – open source serif.

- "Linux Libertine". http://linuxlibertine.sourceforge.net/Libertine-EN.html. – GPL and OPL-licensed serif.

- "Linux Libertine G". http://numbertext.org/linux/. – GPL and OPL-licensed serif.

- "Taigi Unicode". http://www.tailingua.com/resources/downloads/twu3.ttf. – serif font specifically designed for POJ.

Texts and dictionaries

Min Nan Chinese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Min Nan Chinese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia- "Taiwanese bibliography". http://iug.csie.dahan.edu.tw/iug/ungian/Soannteng/subok/poj.htm. – list of books in Taiwanese, including those written in POJ.

- "Memory of Written Taiwanese". http://iug.csie.dahan.edu.tw/memory/TGB/MoWT.asp. – collection of Taiwanese texts in various orthographies, including many in POJ.

- "Tai-Hoa Dictionary". http://210.240.194.97/iug/Ungian/soannteng/chil/Taihoa.asp. – dictionary which includes POJ, Taiwanese in Chinese characters, and Mandarin characters. Some English definitions also available.

- Exhibits: Taiwanese Romanization Peh-oe-ji, http://www.de-han.org/pehoeji/exhibits/index.htm – sample images of various older POJ texts.

- Chinese Character to Pe̍h-ōe-jī Online Transliterator, http://transliterationisfun.blogspot.com/2016/01/chinese-character-to-southern-min.html – Transliterates Southern Min Characters and Mandarin Characters to POJ.

|